Limnoscelis

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Limnoscelis Temporal range: Late Carboniferous - Early Permian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of the L. paludis holotype (YPM 811) on display at the Redpath Museum, Montreal | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Diadectomorpha |

| Family: | †Limnoscelidae |

| Genus: | †Limnoscelis Williston, 1911 |

| Type species | |

| †Limnoscelis paludis Williston, 1911 | |

| Other species | |

| |

Limnoscelis (/limˈnäsələ̇s/, meaning "marsh footed") was a genus of large diadectomorph tetrapods from the Late Carboniferous to early Permian of western North America. It includes two species: the type species Limnoscelis paludis from New Mexico,[1] and Limnoscelis dynatis from Colorado,[2] both of which are thought to have lived concurrently.[3] No specimens of Limnoscelis are known from outside of North America.[1][2][4] Limnoscelis was carnivorous,[1] and likely semiaquatic,[1] though it may have spent a significant portion of its life on land.[5] Limnoscelis had a combination of derived amphibian and primitive reptilian features,[6] and its placement relative to Amniota has significant implications regarding the origins of the first amniotes.[7][8]

Discovery and naming[edit]

The type species Limnoscelis paludis was collected by the fossil hunter David Baldwin between 1877 and 1880[1][9] from the El Cobre Canyon beds[10] of the Cutler Formation, New Mexico.[11] Baldwin was collecting fossils in service of the paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh during the bone wars.[1][12] Although Marsh would describe several specimens from Baldwin's collections,[9] many fossils, including Limnoscelis paludis, would be deposited without description at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale College for several decades.[1]

Limnoscelis paludis was finally described in 1911 by the paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston, who discovered three specimens of the genus in the Yale Peabody Museum collections.[1] These included one relatively complete articulated specimen which included the skull (the holotype, YPM 811), and two less-complete post-cranial skeletons (MCZ 1947 and MCZ 1948, formerly YPM 819 and YPM 809 respectively).[1][2] Williston named the fossil Limnoscelis paludis, referencing the marsh-like environment that he hypothesized Limnoscelis might have inhabited.[1] In 1912, Williston described the discovery of an additional specimen, collected by himself at the same locality as the previous specimens.[4]

More Limnoscelis fossils were collected between 1966 and 1973 by the paleontologist Peter P. Vaughn from the Sangre de Cristo Formation in Colorado,[2][13][14] which would later be attributed to the species Limnoscelis dynatis.[2] Vaughn, however, did not initially recognize these materials as belonging to Limnoscelis, instead attributing several fossil elements to the Rhachitomi or the Anthracosauria.[2][13][14] The presence of Limnoscelis at the locality was finally recognized upon the collection of more fossils from the genus, which would amount to three disarticulated specimens (the holotype CM 47653, and paratypes CM 47651 and CM 47652).[2] These fossils, particularly the holotype, were referenced as representing the genus Limnoscelis in several publications.[3][15] However, the fossils themselves were not recognized as their own species until paleontologists David S. Berman and Stuart S. Sumida described the fossils in 1990.[2] They designated the new species as Limnoscelis dynatis, with “dynatis” being derived from the Greek dynatos meaning “strong” or “powerful”, referencing the genus’ capability as a “formidable predator”.[2]

Description[edit]

The skeleton of Limnoscelis was relatively large, with Limnoscelis paludis measuring 7 feet (around 2 meters) long.[1] Portions of the skeleton are poorly ossified, with many cartilaginous elements.[1][6]

Skull and teeth[edit]

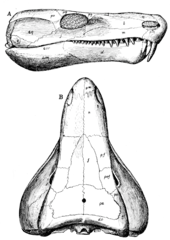

Limnoscelis had a relatively elongated skull, with a narrow snout and wider posterior region.[1][6] Its teeth were conical[1] and labyrinthodont, with infolding of enamel and dentin.[1][2] Limnoscelis had particularly well-developed incisors,[1][6] peaking in size at the anterior maxilla, similar to the placement of the canine tooth of many derived synapsids.[6] This tooth morphology has been used to infer that Limnoscelis was a carnivore.[1] The mandible of Limnoscelis was well-built, with large processes for jaw muscle attachment, indicating that it had a powerful bite.[1] In addition to its premaxillary, maxillary, and dentary teeth, Limnoscelis had additional palatal teeth on transverse flanges of its pterygoid.[1][6] These flanges consisted of an anterior row of smaller blunt denticles, and a posterior row of larger teeth, with neither having labyrinthodont infolding.[2] The pterygoid of Limnoscelis articulated with the basisphenoid.[1] The occipital region of Limnoscelis was relatively flat,[1] similar to that of some basal synapsids.[6] Limnoscelis had a single occipital condyle.[6] Limnoscelis had an anapsid skull fenestration pattern, lacking temporal fenestrae.[1] However, the supratemporal of Limnoscelis has been pushed posteriorly and ventrally,[6] creating a “line of weakness” between the supratemporal, postorbital, and squamosal bones.[1][6][16] This “line of weakness” has been proposed to be a precursor to the synapsid temporal fenestra,[16] although this hypothesis has been challenged.[17]

Axial skeleton[edit]

Limnoscelis had 26 presacral vertebrae.[4] These vertebrae had swollen neural arches,[1] and amphicoelous notochordal centra.[5] The vertebrae of Limnoscelis were typically longer than they were wide,[5] but varied in size and shape throughout the vertebral column,[2][5][18] along with neural spine height.[5][19] Limnoscelis had a multipartite atlas and axis complex, with a ventral anterior process of the axis intercentrum articulating with that of the atlas.[18] Limnoscelis had single headed ribs,[1] though they might have had cartilaginous caps to allow the passage of the vertebral artery between the capitulum and tubercle of each rib.[6] Limnoscelis had two sacral vertebrae,[5][19] a feature shared with amniotes,[20] though the second sacral vertebra is reduced compared to the first.[5]

Appendicular skeleton[edit]

The pectoral girdle of Limnoscelis consisted of a single interclavicle, with paired clavicles, scapulocoracoids, and cleithra on its right and left sides.[5] The cleithrum was small and possibly vestigial,[1][6] indicating further ossification of the scapulocoracoid.[6] Limnoscelis may also have had cartilaginous extensions above the scapolocoracoid, compensating for this reduction in size.[6] The scapulocoracoid of Limnoscelis had two fused coracoid elements, which it shares with a number of basal amniotes, but which differentiates Limnoscelis from its fellow diadectomorphs (which only had a single coracoid).[6] The ilium of Limnoscelis possessed an iliac shelf, a low ridge extending anteroposteriorly across the dorsal ilium,[6] a synapomorphy of the Diadectomorpha.[2] The forelimbs and hindlimbs of Limnoscelis were short and robust, giving the animal a low sprawling posture.[1][5] It had a phalangeal formula of 2-3-4-5-3 for the manus, and a formula of 2-3-4-5-4 for the pes,[1] which it shared with basal amniotes.[5] Originally, it was thought that Limnoscelis possessed two proximal tarsals, consisting of the fibulare and a preaxial element comprising a fused tibiale and intermedium.[1] However, subsequent analyses have cast doubt on this assessment, instead proposing that the two preserved proximal tarsals are the fibulare and intermedium, and that Limnoscelis possessed an unfused tibiale along with these elements.[5][6][21] The absence of the tibiale has been attributed either to poor preservation (possibly due to being cartilaginous),[5][6] or to being displaced and misidentified as one of the distal tarsals.[21] This differs from other diadectomorphs in the family Diadectidae, which possessed an astragalus consisting of a fused tibiale, intermedium, and proximal centrale, similar (and possibly homologous) to the astragalus or talus bone found in amniotes.[21]

Differences between L. dynatis and L. paludis[edit]

A number of features distinguish Limnoscelis dynatis from the type species Limnoscelis paludis. L. dynatis is thought to be the smaller of the two genera, estimated to be about 20% smaller than L. paludis.[2] The premaxilla differs considerably between the species. While the premaxilla of L. paludis was relatively large, enclosing the entire external naris, the premaxilla of L. dynatis was significantly smaller, with the ventral border of the external naris instead being formed by the maxilla.[2] L. dynatis had smaller teeth, but had more of them compared to L. paludis.[2] The ridge of the pterygoid flange of L. dynatis was narrow compared to L. paludis, possessing smaller teeth and denticles.[2] The supraoccipital of L. paludis consisted of a single element, while it consisted of two paired elements in L. dynatis.[22] The scapulocoracoid of L. dynatis was shorter and wider than the scapulocoracoid of L. paludis,[2] while also being thinner and less convex.[5] Similarly, the ilium of L. dynatis was also shorter and wider than that of L. paludis.[2] The proximal limb bones (humerus and femur) of L. dynatis were shorter relative to body size compared to those of L. paludis, while its distal limb bone elements (radius, ulna, tibia, and fibula) were longer.[5] Many of these features appear more derived in L. paludis, leading some to consider it to be the more derived of the two species.[2]

Classification[edit]

In its earliest descriptions, Limnoscelis was identified as an early reptile, thought to be closely related to the Captorhinidae or Pareiasauridae based on its flat occiput,[1] as well as its large upper incisors and broad parareptile-like neural arches.[6] However, Williston noted enough differences from these groups to place Limnoscelis within its own subfamily, the Limnoscelidae,[1] which would later be erected as its own family.[23] Limnoscelidae once contained the genera Limnosceloides, Limnoscelops, and Limnostygis, but is currently monogeneric, containing only Limnoscelis.[24]

Relationship with the Diadectomorpha[edit]

These early descriptions framed Limnoscelis as a member of the paraphyletic group Captorhinomorpha within Cotylosauria, alongside the clades Diadectomorpha and Seymouriamorpha.[25] However, these early authors also noted many similarities between Limnoscelis and the diadectid Diadectes, including the bones forming the orbital border, the presence of a glenoid foramen on the scapula, and having similar pectoral and pelvic girdles.[1] Differences were noted as well, including having a single continuous rib articulation rather than double-headed ribs,[1] its conical teeth and carnivorous diet,[12] the lack of a fused astragalus,[5][6] and the presence of two fused coracoid elements rather than a single element in the coracoid plate.[6] Despite these differences, the similarities with Diadectes would eventually be used to place Limnoscelis at its current taxonomic position as a diadectomorph, with Limnoscelidae erected as a family within the order Diadectomorpha alongside the family Diadectidae and the genus Tseajaia from the monogeneric family Tseajaiidae.[23] This monophyletic grouping of Diadectomorpha is supported by the anterior processes of the atlas and axis intercentra, and the presence of an external iliac shelf,[5][26] features that are shared by all diadectomorphs.[26] Within the Diadectomorpha, Limnoscelis is often found to be sister to Diadectidae and Tseajaia, with the later clades forming a monophyletic group in many cladistic analyses.[7][8][18][20][23][27][28][29][30]

The below cladogram shows the order Diadectomorpha, modified from Heaton (1980).[23]

| ||||||||||

Relationship with Amniota and Synapsida[edit]

Due to its highly generalized post-cranial morphology, Limnoscelis has long been thought to be morphologically similar to a hypothetical ancestor of all amniotes,[3][6] although its occurrences are too recent to be this ancestor itself.[6] Limnoscelis possessed several reptilian cranial homologies, including the closure of the otic notch and the development of a pterygoid flange on the palatal surface, while retaining a generalized amphibian-like postcranial morphology.[6] Furthermore, it was noted that Limnoscelis shared many features with early Pelycosaurs like Ophiacodon, particularly in its post-cranial skeleton.[6] Others disagreed, citing differences in the postorbital bone,[31] and arguing that a hypothetical ancestor of all amniotes should be small enough to efficiently produce the amniotic egg,[32] with Limnoscelis having been too big to have been this ancestor.[31] The relationship between Limnoscelis and amniotes was later expanded upon, with several features of the skull of Limnoscelis suggesting that it might not only be representative of the ancestor of all amniotes, but representative of the pre-synapsid condition as well.[16] These included a large supratemporal bone contacting the postorbital anteriorly, and a line of weakness between the postorbital, supratemporal, and squamosal bones which could eventually develop into the temporal fenestra of synapsids.[16] However, several authors argued against the validity of these characters.[17]

Many recent studies have focused on the placement of Limnoscelis and the Diadectomorpha relative to Amniota and Synapsida. Heaton's originally classified the diadectomorphs as amphibians, outside of and sister to Amniota.[23] However, subsequent studies have argued for a close relationship between diadectomorphs and synapsids, with many cladistic analyses placing them as sister taxa.[8][18][22][33][34] This grouping is based on a variety of shared characters, including the possession of an otic trough,[8] having similar atlas-axis complexes,[18] the possession of small posttemporal fenestrae,[22] the possession of a small parietal foramen, the structure and position of the septomaxillae, and the possession of a tall, broad, and flat ilium.[33] Most recently, a study of the inner ear morphology of diadectomorphs using X-ray microcomputed tomography by Klembara et al. also supported the close relationship between diadectomorphs and synapsids.[34] If this relationship is true, it would make all Diadectomophs, including Limnoscelis, crown amniotes.[8] The placement of Limnoscelis and other diadectomorphs within Amniota is supported by other shared characters, including the loss of the intertemporal bone, absence of the temporal notch, presence of an ossified supraoccipital,[8] shared digital formulas,[5] and the possession of a ventrally displaced, laterally directed paroccipital process.[22] While Limnoscelis itself lacked an astragalus,[5][6][21] this feature is present in the diadectidae, which could be further evidence uniting the Diadectomorpha with amniotes.[21] However, this may also be the result of convergent evolution.[21] Other studies question the reliability of the characters allying Diadectomorpha with Synapsida, instead agreeing with Heaton's original placement of the Diadectomorpha outside of Amniota, with the two clades remaining sister taxa.[7][17][20][28][29] Some also argue that Amniota should be defined by the use of the amniotic egg, and that there is little evidence regarding the potential use of this reproductive strategy by Limnoscelis, making it difficult to determine its placement relative to amniotes.[27]

The below cladogram, modified from Laurin and Reisz (1995), showing Limnoscelis and the Diadectomorpha sister to Amniota,[7] agreeing with the original placement from Heaton (1980).[23]

| |||||||||||||||||||

The below cladogram, modified from Berman et al. (1992),[8] depicting the alternative hypothesis placing Limnoscelis and the Diadectomorpha as sister to Synapsida within Amniota.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology[edit]

In its earliest descriptions by Williston, Limnoscelis was characterized as a slow but nonetheless powerful animal.[1] Poor ossification of the cranium,[1][6] along with its short limbs and flattened tail,[4] suggest that it likely had an aquatic or semiaquatic lifestyle.[1][4][6] Williston hypothesized that Limnoscelis might have used the water to hide from predators, or look to for food.[4] Alfred Sherwood Romer suggested that this might be a retention of an ancestral semiaquatic lifestyle found in amphibians, which might have also been retained in some early pelycosaurs.[6] However, other studies have suggested a significantly more terrestrial lifestyle for Limnoscelis, based on relatively well-ossified portions of its post-cranial skeleton.[5]

Despite its long conical teeth indicating a carnivorous diet,[1] Williston doubted that Limnoscelis could have been a predator, as he believed its short, robust limbs made it too slow to pursue prey.[1][4] Instead, he hypothesized that Limnoscelis might have fed on invertebrates.[4] However, Romer argued that Limnoscelis could have been a successful semiaquatic predator, comparing its anatomy with that of known aquatic predators like crocodilians and phytosaurs.[6] Several subsequent analyses have agreed with Romer's argument, and most studies agree that Limnoscelis most likely had a predatory lifestyle.[2][3] This differs significantly from most other diadectomorphs, particularly the family Diadectidae, which were herbivorous.[35]

Paleoecology[edit]

Limnoscelis paludis[edit]

Limnoscelis paludis is endemic to the El Cobre Canyon beds of the Cutler Formation, New Mexico.[4] This site was originally thought to be early Permian in age,[9] though later studies concluded that the lower beds of the formation were actually from the Late Carboniferous based on biostratigraphy using the brachiopod Anthracospirifer rockymontanus.[10] Limnoscelis paludis was found in these lower beds, suggesting that it might have been restricted to a similar age.[10] However, dating of these lower beds to the late Pennsylvanian was initially found to be dubious based on inconsistencies with the stratigraphic placement of the fossils used for biostratigraphy.[36] An early Permian age again fell into favor, based on faunal similarities with the Arroyo del Agua beds of the Cutler Formation.[36][37] However, later studies again confirmed a Late Pennsylvanian age based on biostratigraphy using several new marker fossils, with Limnoscelis paludis belonging to this Late Pennsylvanian assemblage.[11] The El Cobre Canyon formation is thought to represent an alluvial plane, with a single-channel meandering river in a semi-arid environment,[3] being one of the earliest representations of a terrestrial fauna.[11] Being semiaquatic, Limnoscelis paludis would have probably inhabited this river.[3] The river is thought to have flooded seasonally with the rains, possibly drying up completely between the rainy seasons, and forming new channels on an annual to semi-annual basis.[3] To cope with the dry periods between the seasonal rains, it has been proposed that Limnoscelis might have aestivated during these periods, with the close stratigraphic association of the original specimens found by Baldwin being possible evidence of a communal aestivation den.[3]

The environment of Limnoscelis paludis would have likely been dominated by pelycosaurs and other basal synapsids,[3] including Sphenacodon ferox,[1][9][11][12] Ophiacodon mirus,[1][9][12] Ophiacodon navajovicus,[1][11] Clepsydrops vinslovii,[1][12] Aerosaurus greenleeorum,[11] and Edaphosaurus novomexicanus.[11][12] Limnoscelis paludis also likely lived alongside other diadectomorphs, including Diadectes lentus,[1][9][12] Diasparactus zenos,[1][11] and Desmatodon hollandi.[11] Also sharing the landscape were several amphibians, including Seymouria sanjuanensis,[38] and the temnospondyls Eryops grandis,[1][9][12] Platyhystrix rugosus,[1][11][12] Aspidosaurus novomexicanus,[1][11][12] and Chenoprosopus milleri.[11] Williston noted a lack of fish and shark fossils from the site,[1] supporting the sites reconstruction as a terrestrial, semi-arid, seasonal floodplain.[3] It is possible, however, that the faunal assemblage at El Cobre Canyon represents two horizons, with species including Limnoscelis paludis and Desmatodon hollandi inhabiting the lower (Late Carboniferous) assemblage, and other species including Edaphosaurus novomexicanus, Platyhystrix rugosus, Sphenacodon ferox, Aspidosaurus novomexicanus, and Ophiacodon navajovicus inhabiting the upper (Early Permian) assemblage.[3]

Limnoscelis dynatis[edit]

Limnoscelis dynatis is known from the Sangre de Cristo Formation in Colorado,[2] which is thought to be stratigraphically equivalent to the Cutler Formation[3] and dated to a similar Late Pennsylvanian age.[13] Limnoscelis dynatis fossils have been found alongside the synapsids Edaphosaurus raymondi,[13] and Xyrospondylus ecordi,[14] the diadectid Desmatodon hesperis,[13] the aïstopod Coloraderpeton brilli,[13] the microsaur Trihecaton howardinus,[14] and labyrinthodont amphibians.[13] The presence of paleoniscoid fish[13] and a xenacanth shark[14] indicate the presence of water, with the site possibly representing an oxbow lake.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av Williston, S.W. (1911). "A new family of reptiles from the Permian of New Mexico". The American Journal of Science. 4. 33 (185): 378–398. Bibcode:1911AmJS...31..378W. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-31.185.378.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Berman, D.S.; Sumida, S.S. (1990). "A new species of Limnoscelis (Amphibia, Diadectomorpha) from the Late Pennsylvanian Sangre de Cristo Formation of Central Colorado". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 59 (4): 303–341. doi:10.5962/p.240774. S2CID 92022042.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fracasso, M.A. (1983). "Cranial Osteology, Functional Morphology, Systematics, and Paleoenvironment of Limnoscelis paludis Williston". Dissertation.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Williston, S.W. (1912). "Restoration of Limnoscelis, a Cotylosaur Reptile from New Mexico". The American Journal of Science. 4. 40 (203): 457–468. Bibcode:1912AmJS...34..457W. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-34.203.457.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Kennedy, N.K. (2010). "Redescription of the Postcranial Skeleton of Limnoscelis paludis Williston (Diadectomorpha: Limnoscelidae) from the Upper Pennsylvanian of El Cobre Canyon, Northern New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 49: 211–220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Romer, A.S. (1946). "The Primitive Reptile Limnoscelis Restudied". The American Journal of Science. 244 (3): 149–188. Bibcode:1946AmJS..244..149R. doi:10.2475/ajs.244.3.149.

- ^ a b c d Laurin, M.; Reisz, R.R. (1995). "A Reevaluation of Early Amniote Phylogeny". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113 (2): 165–223. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1995.tb00932.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g Berman, D.S.; Sumida, S.S.; Lombard, R.E. (1992). "Reinterpretation of the Temporal and Occipital Regions in Diadectes and the Relationships of Diadectomorphs". Journal of Paleontology. 66 (3): 481–499. Bibcode:1992JPal...66..481B. doi:10.1017/S0022336000034028. S2CID 73547163.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marsh, O.C. (1878). "Notice of New Fossil Reptiles". The American Journal of Science. 3. 89: 409–411.

- ^ a b c Williston, S.W.; Case, E.C. (1912). "The Permo-Carboniferous of Northern New Mexico". The Journal of Geology. 20 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:1912JG.....20....1W. doi:10.1086/621924. S2CID 140631710.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fracasso, M.A. (1980). "Age of the Permo-Carboniferous Cutler Formation Vertebrate Fauna from El Cobre Canyon, New Mexico". Journal of Paleontology. 54 (6): 1237–1244.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Williston, S.W. (1911). "American Permian Vertebrates". University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Il.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vaughn, P.P. (1969). "Upper Pennsylvanian vertebrates from the Sangre de Cristo Formation of central Colorado". Contributions in Science, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. 164: 1–28.

- ^ a b c d e Vaughn, P.P. (1972). "More vertebrates, including a new microsaur, from the Upper Pennsylvanian of central Colorado". Contributions in Science, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. 223: 1–30.

- ^ Fracasso, M.A. (1987). "Braincase of Limnoscelis paludis Williston". Postilla, Yale University. 201: 1–22.

- ^ a b c d Kemp, T.S. (1980). "Origin of the mammal-like reptiles". Nature. 283 (5745): 378–380. Bibcode:1980Natur.283..378K. doi:10.1038/283378a0. S2CID 4330876.

- ^ a b c Reisz, R.R.; Heaton, M.J. (1980). "Origin of mammal-like reptiles". Nature. 288 (5787): 193. Bibcode:1980Natur.288..193R. doi:10.1038/288193a0. S2CID 7858734.

- ^ a b c d e Sumida, S.S.; Lombard, R.E.; Berman, D.S. (1992). "Morphology of the atlas-axis complex of the late Paleozoic tetrapod suborders Diadectomorpha and Seymouriamorpha". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 336 (1277): 259–273. doi:10.1098/rstb.1992.0060.

- ^ a b Sumida, S.S. (1990). "Vertebral morphology, alternation of neural spine height, and structure in Permo-Carboniferous tetrapods, and a reappraisal of primitive modes of terrestrial locomotion". University of California Publications in Zoology. 122: 1–133.

- ^ a b c Gauthier, J.; Kluge, A.G.; Rowe, T (1988). "The early evolution of the Amniota". In Benton, M. J. (ed.). The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 103–155.

- ^ a b c d e f Berman, D.S.; Henrici, A.C. (2003). "Homology of the Astragalus and Structure and Function of the Tarsus of Diadectidae". Journal of Paleontology. 77 (1): 172–188. doi:10.1017/S002233600004350X.

- ^ a b c d Berman, D.S. (2000). "Origin and Evolution of the Amniote Occiput". Journal of Paleontology. 74 (5): 938–956. doi:10.1017/S0022336000033114.

- ^ a b c d e f Heaton, M.J. (1980). "The Cotylosauria: A reconsideration of a group of archaic tetrapods". In Panchen, A. L. (ed.). The Terrestrial Environment and the Origin of Land Vertebrates. London: Academic Press. pp. 497–551.

- ^ Wideman, N.K. (2002). "The postcranial anatomy of the late Paleozoic Family Limnoscelidae and its significance for diadectomorph taxonomy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22: 119A.

- ^ Watson, D.M.S. (1917). "A Sketch Classification of the Pre-Jurassic Tetrapod Vertebrates". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 87 (1): 167–186. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1917.tb02055.x.

- ^ a b Sumida, S.S. (1997). "Locomotor features of taxa spanning the origin of amniotes". In Sumida, S. S.; Martin, K. L. M. (eds.). Amniote origins: Completing the transition to land. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 353–398.

- ^ a b Lee, M.S.Y.; Spencer, P.S. (1997). "Crown-clades, Key Characters and Taxonomic Stability: When is an Amniote not an Amniote?". In Sumida, S. S.; Martin, K. L. M. (eds.). Amniote Origins: Completing the Transition to Land. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 61–84.

- ^ a b Kissel, R.A.; Reisz, R.R. (2004). "Ambedus pusillus, new genus and species, a small diadectid (Tetrapoda, Diadectomorpha) from the Lower Permian of Ohio, with consideration of diadectomorph phylogey". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 73: 197–212. doi:10.5962/p.215153. S2CID 90384814.

- ^ a b Kissel, R.A. (2010). "Morphology, Phylogeny and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)". Graduate Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. University of Toronto.

- ^ Benson, R.B.J. (2012). "Interrelationships of basal synapsids: cranial and postcranial morphological partitions suggest different topologies". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (4): 601–624. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.631042. S2CID 84706899.

- ^ a b Panchen, A.L. (1972). "The Interrelationships of the Earliest Tetrapods". In Joysey, K.; Kemp, T. (eds.). Studies in Vertebrate Evolution. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 65–87.

- ^ Carroll, R.L. (1969). "Problems of the Origin of Reptiles". Biological Reviews. 44 (3): 393–431. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1969.tb01218.x. S2CID 84302993.

- ^ a b Berman, D.S. (2013). "Diadectomorphs: amniotes or not?". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 60: 22–35.

- ^ a b Klembara, J.; Hain, M.; Ruta, M.; Berman, D.S.; Pierce, S.E.; Henrici, A.C. (2020). "Inner Ear Morphology of Diadectomorphs and Seymouriamorphs (Tetrapoda) Uncovered by High-Resolution X-Ray Microcomputed Tomography, and the Origin of the Amniote Crown Group". Palaeontology. 63 (1): 131–154. doi:10.5061/dryad.4j2tp4s.

- ^ Cope, E.D. (1878). "Descriptions of Extinct Batrachia and Reptilia from the Permian Formation of Texas". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 17 (101): 505–530.

- ^ a b Langston, W. (1953). "Permian amphibians from New Mexico". University of California Publications in Geological Sciences. 29 (7): 349–416.

- ^ Vaughn, P.P. (1963). "The Age and Locality of the Late Paleozoic Vertebrates from El Cobre Canyon, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico". Journal of Paleontology. 37 (1): 283–286.

- ^ Berman, D.S.; Reisz, R.R.; Eberth, D.A. (1987). "Seymouria sanjuanensis (Amphibia, Batrachosauria) from the Lower Permian Cutler Formation of north-central New Mexico and the occurrence of sexual dimorphism in that genus questioned". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 24 (9): 1769–1784. Bibcode:1987CaJES..24.1769B. doi:10.1139/e87-169.