Milton Caniff

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

| Milton Caniff | |

|---|---|

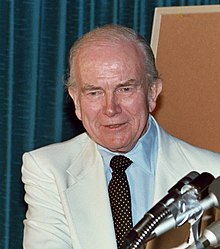

Milton Caniff in 1982 | |

| Born | Milton Arthur Paul Caniff February 28, 1907 Hillsboro, Ohio, US |

| Died | April 3, 1988 (aged 81) New York City, US |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

Notable works | Dickie Dare Terry and the Pirates Steve Canyon |

| Awards | Full list |

Milton Arthur Paul Caniff (/kəˈnɪf/; February 28, 1907 – April 3, 1988) was an American cartoonist known for the Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon comic strips.[1]

Biography[edit]

Caniff was born in Hillsboro, Ohio. He was an Eagle Scout[2] and a recipient of the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award from the Boy Scouts of America. Caniff did cartoons for local newspapers while studying at Stivers High School (now Stivers School for the Arts) in Dayton Ohio. At Ohio State University, Caniff joined the Sigma Chi fraternity and later illustrated for The Magazine of Sigma Chi and The Norman Shield (the fraternity's pledgeship/reference manual). Graduating in 1930, Caniff began at the Columbus Dispatch where he worked with the noted cartoonists Billy Ireland and Dudley Fisher, but Caniff's position was eliminated during the Great Depression. Caniff related later that he had been uncertain of whether to pursue acting or cartooning as a career and that Ireland said, "Stick to your inkpots, kid, actors don't eat regularly."[3]

He died on April 3, 1988, and was buried in the Mount Repose Cemetery, Haverstraw, New York.

Comic strips[edit]

In 1932, Caniff moved to New York City to accept an artist job with the Features Service of the Associated Press. He did general assignment art for several months, drawing the comic strips Dickie Dare and The Gay Thirties,[4] then inherited a panel cartoon named Mister Gilfeather in September 1932 when Al Capp quit the feature.

Caniff was also hired by his friend Bil Dwyer when Dwyer took over the Chic Young-created comic strip Dumb Dora in 1932, and needed help while learning the routines of a daily cartoon strip. Caniff ghost-wrote and drew a number of strips, working closely with Dwyer for the first year and a half of Dwyer's tenure on the strip. While some critics claimed that Caniff was largely responsible for the strip's quality at this time, Caniff himself took credit only for some of the art and none of the writing, calling Dwyer "a good gag man."[5][6]

Caniff continued Gilfeather until the spring of 1933, when it was retired in favor of a generic comedy panel cartoon called The Gay Thirties, which he produced until he left AP in the autumn of 1934. In July 1933, Caniff began an adventure fantasy strip, Dickie Dare, influenced by series such as Flash Gordon and Brick Bradford.[7] The eponymous main character was a youth who dreamed himself into adventures with such literary and legendary persons as Robin Hood, Robinson Crusoe and King Arthur. In the spring of 1934, Caniff changed the strip from fantasy to "reality" when Dickie no longer dreamed his adventures but experienced them as he traveled the world with a freelance writer, Dickie's adult mentor, "Dynamite Dan" Flynn.

Terry and the Pirates[edit]

In 1934, Caniff was hired by the New York Daily News to produce a new strip for the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate. Daily News publisher Joseph Medill Patterson wanted an adventure strip set in the mysterious Orient, what Patterson described as "the last outpost for adventure,"[8] Knowing almost nothing about China, Caniff researched the nation's history and learned about families for whom piracy was a way of life passed down for generations. The result was Terry and the Pirates, the strip which made Caniff famous.[7] Like Dickie Dare, Terry Lee began as a boy who is traveling with an adult mentor and adventurer, Pat Ryan. But over the years the title character aged, and by World War II he was old enough to serve in the Army Air Force. During the 12 years that Caniff produced the strip, he introduced many fascinating characters, most of whom were "pirates" of one kind or another.

Introduced during the early days of the strip was Terry and Pat's interpreter and manservant Connie. They were later joined by the mute Chinese giant Big Stoop. Both he and Connie provided the main source of comic relief. Other characters included: Burma, a blonde with a mysterious, possibly criminal, past; Chopstick Joe, a Chinese petty criminal; Singh Singh, a warlord in the mountains of China; Judas, a smuggler; Sanjak, a lesbian; and then boon companions such as Hotshot Charlie, Terry's wing man during the War years; and April Kane, a young woman who was Terry's first love.

But Caniff's most memorable creation was the Dragon Lady, a pirate queen; she was seemingly ruthless and calculating, but Caniff encouraged his readers to think she had romantic yearnings for Pat Ryan.

Male Call[edit]

During the war, Caniff began a second strip, a special version of Terry and the Pirates without Terry but featuring the blonde bombshell, Burma. Caniff donated all of his work on this strip to the armed forces—the strip was available only in military newspapers. After complaints from the Miami Herald about the military version of the strip being published by military newspapers in the Herald's circulation territory, the strip was renamed Male Call and given a new star, Miss Lace, a beautiful woman who lived near every military base and enjoyed the company of enlisted men, whom she addressed as "Generals". Her function, Caniff often said, was to remind service men what they were fighting for, and while the situations in the strip included much 'double entendre', Miss Lace was not portrayed as being promiscuous.

Much more so than civilian comic strips which portrayed military characters, Male Call was notable for its honest depiction of what the servicemen encountered; one strip displays Lace dating a soldier on leave who had lost an arm (she lost her temper when a civilian insulted him for that disability). Another strip had her dancing with a man in civilian clothes; a disgruntled GI shoved and mocked him for having an easy life, but Lace's partner was in fact an ex-GI blinded in battle. Caniff continued Male Call until seven months after V-J Day, ending it in March 1946.[9]

In 1946, Caniff ended his association with Terry and the Pirates. While the strip was a major success, it was not owned by its creator but by its distributing syndicate, the Chicago Tribune-New York Daily News, a common practice with syndicated comics at the time. And when Caniff, growing more and more frustrated with the lack of rights to the comic strip he produced, was offered the chance to own his own strip by Marshall Field, publisher of the Chicago Sun, the cartoonist quit Terry to produce a strip for Field Enterprises. Caniff produced his last strip of Terry and the Pirates in December 1946 and introduced his new strip Steve Canyon in the Chicago Sun-Times the following month.[7] At the time, Caniff was one of only two or three syndicated cartoonists who owned their creations, and he attracted considerable publicity as a result of this circumstance.

Steve Canyon[edit]

Like his previous strip, Steve Canyon was an action strip with a pilot as its main character. Canyon was portrayed originally as a civilian pilot with his own one-airplane cargo airline, but he re-enlisted in the Air Force during the Korean War and remained in the Air Force for the remainder of the strip's run.

While Steve Canyon never achieved the popularity that Terry and the Pirates had as a World War II military adventure, it was a successful comic strip with a greater circulation than Terry ever had. A short-lived Steve Canyon television series was produced in 1958. Steve Canyon was often termed the "unofficial spokesman" for the Air Force. The title character's dedication to the military produced a negative reaction among readers during the Vietnam War, and the strip's circulation decreased as a result. Caniff nonetheless continued to enjoy enormous regard in the profession and in newspapering, and he produced the strip until his death in 1988. The strip was published for a couple of months after he died, but was ended in June 1988, due to Caniff's decision that no one else would continue the feature.

The character of Charlie Vanilla, who appeared frequently with an ice cream cone, was based on Caniff's long-term friend Charles Russhon, a former photographer and Lieutenant in the US Air Force who later worked as a James Bond movie technical adviser.[10] The character of Madame Lynx was based on Madame Egelichi, the femme fatale spy played by Ilona Massey in the 1949 Marx Brothers movie Love Happy. The character stirred Caniff's imagination, and he hired Ilona Massey to pose for him.[11] Caniff designed Pipper the Piper after John F. Kennedy and Miss Mizzou after Marilyn Monroe.[11]

Recognition and awards[edit]

Caniff was one of the founders of the National Cartoonists Society and served two terms as its president, 1948 and 1949. He also received the Society's first Cartoonist of the Year Award in 1947 for work published during 1946, which included both Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates as well. Caniff would be named Cartoonist of the Year again, receiving the accompanying trophy, the Reuben, in 1972 for 1971, again for Steve Canyon. He was awarded an Inkpot Award in 1974.[12]

He was inducted into the comic book industry's Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 1988. He received the National Cartoonists Society Elzie Segar Award in 1971, the Award for Story Comic Strip in 1979 for Steve Canyon, the Gold Key Award (the Society's Hall of Fame) in 1981, and the NCS has since named the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in his honor.

In 1977, the Milton Caniff Collection of papers and original art became the foundation for what is known presently as the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. Covering 696 cubic feet (19.7 m3), the collection fills 526 boxes, plus 12,153 art originals and 59 oversized items. In addition to the original artwork, the collection includes Caniff's personal and business papers, correspondence, research files, photographs, memorabilia, merchandise, realia, awards, audio/visual material and scrapbooks.

In 1987, he was made the first honorary member of the Eighth Air Force Historical Society in recognition for the "Male Call" strip that he did for Stars and Stripes during World War II.[13]

Influence[edit]

Caniff died in New York City in 1988. Along with Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, Caniff's style had a tremendous influence on the artists who drew American comic books and adventure strips during the mid-20th century. Evidence of his influence can be seen in the work of comic book/strip artists such as Jack Kirby, Frank Robbins, Lee Elias, Bob Kane, Mike Sekowsky, John Romita, Sr., Johnny Craig, William Overgard and Doug Wildey to name just a few. European artists were also influenced by his style, including Belgian artists Jijé, Hubinon and Italian artist Hugo Pratt.

The Caniff estate hired special effects artist John R. Ellis to restore for release the 34 episodes of the 1958–59 NBC television series Steve Canyon featuring Dean Fredericks in the title role.[14]

Caniff as comic character[edit]

From 1995, Dargaud has published a series of Franco-Belgian comics, Pin-Up, intended mainly for adults, written by Yann Le Pennetier and drawn by Philippe Berthet. The series describes the adventures of artist's model Dottie Partington during and after World War II. The strip features a number of real-life characters and situations, albeit in a fictional setting, including Gary Powers and the U-2 Crisis and Hugh Hefner. During World War II, Dottie is the model for Milton, an artist who has been commissioned to draw a strip to raise the morale of the troops. He creates Poison Ivy, a strip-within-a-strip, in which the titular character is a combination of Lace of Male Call and Mata Hari (though she fights with the Yanks against the Japanese). Milton is later shown working on Steve Canyon.

This version of Caniff is not a particularly sympathetic one, depicting him in a loveless marriage while obsessed with Dottie who has rejected him.

Bibliography[edit]

- Caniff, Milton Arthur (1975). Enter the Dragon Lady: From the 1936 classic newspaper adventure strip (The Golden age of the comics). Escondido, California: Nostalgia Press. ASIN B0006CUOBW.

- Caniff, Milton Arthur (2007). The Complete Terry And The Pirates. San Diego, California: IDW (Idea and Design Works). ISBN 978-1-60010-100-7.

References[edit]

- ^ "Milton Caniff | American cartoonist | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ^ "Fact Sheet Eagle Scouts". Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ Current Biography 1944, pp. 83–85

- ^ Current Biography 1944, p. 83

- ^ Caniff, Milton Arthur (2002). Milton Caniff: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-437-3.

- ^ R.C. Harvey (12 July 2007). Meanwhile...: A Biography of Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. Fantagraphics Books. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-1-56097-782-7.

- ^ a b c "Milton Caniff". Comiclopedia. Lambiek.

- ^ Current Biography 1944, p84

- ^ "Milton Caniff Biography". Checker Book Publishing Group. Archived from the original on 2007-11-01.

- ^ "Charles J. Russhon, 71, Dies; Basis of Comic Strip Figure". The New York Times. 1982-06-28. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ a b Pageant May 1953, V8 n11

- ^ Inkpot Award

- ^ McQuiston, John T. (1988-04-04). "Milton Caniff, 81, Creator of 'Steve Canyon,' Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ "Ellis to be featured at Reel Stuff Film Festival of Aviation". Wilmington, Ohio, News Journal, March 11, 2009. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- Abrams, Harry N. (1978). Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics'. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-8109-1612-8.

- Harvey, Robert C. and Milton Caniff (2002). Milton Caniff: Conversations (Conversations with Comic Artists series). Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-438-0.

- Harvey, Robert C. Meanwhile... Fantagraphics Books, 2007. ISBN 1-56097-782-5.

- Marschall, Rick and Adams, John Paul. Milton Caniff, Rembrandt of the comic strip. Flying Buttress Publications, 1981. ISBN 0-918348-04-8.

- Mullaney, Dean. Caniff: A Visual Biography, Idea & Design Works, 2011. ISBN 978-1-60010-920-1.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum: Milton Caniff Collection

- digital exhibit: "Milton Caniff an American Master" at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

- "How to Spot a Jap": Educational comic strip by Milton Caniff

- The Will to Win: comic book Milton Caniff created for Goodwill Industries on overcoming disabilities

- 1944 Army Air Forces class book for Perrin Field (Sherman, Texas) with Miss Lace cartoon dedicated to the graduating class

- Milton Caniff at Find a Grave