New Orleans in the American Civil War

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

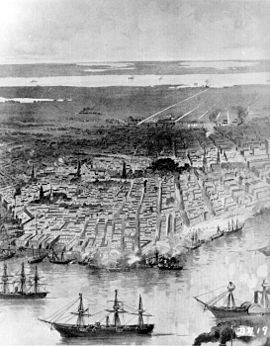

New Orleans, Louisiana, was the largest city in the South, providing military supplies and thousands of troops for the Confederate States Army. Its location near the mouth of the Mississippi made it a prime target for the Union, both for controlling the huge waterway and crippling the Confederacy's vital cotton exports.

In April 1862, the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Captain David Farragut shelled the two substantial forts guarding each of the river-banks, and forced a gap in the defensive boom placed between them. After running the last of the Confederate batteries, they took the surrender of the forts, and soon afterwards the city itself, without further action. The new military governor, Major General Benjamin Butler, proved effective in enforcing civic order, though his methods aroused protest everywhere. One citizen was hanged for tearing down the US flag, and any woman insulting a Federal soldier would be treated as a prostitute. Looting by troops was also rife, though apparently not with Butler's approval. He was eventually replaced by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, who somewhat improved relations between troops and citizens, but military occupation had to continue well after the war.

The prompt surrender of the city had saved it from serious damage, so it remains notably well-preserved today.

Early war years[edit]

The early history of New Orleans was one of uninterrupted growth. In the 1850 census, New Orleans ranked as the 6th largest city in the United States, with a population reported as 168,675.[2] It was the only city in the South with over 100,000 people. By 1840 New Orleans had the largest slave market in the nation, which contributed greatly to its wealth. During the antebellum years, two-thirds of the more than one million slaves who moved from the Upper South in forced migration to the Deep South were taken in the slave trade. Estimates are that the slaves generated an ancillary economy valued at 13.5 percent of the price per person, generating tens of billions of dollars through the years.[3]

Antebellum New Orleans was the commercial heart of the Deep South, with cotton comprising fully half of the estimated $156,000,000 (in 1857 dollars) exports, followed by tobacco and sugar. Over half of all the cotton grown in the U.S. passed through the port of New Orleans (1.4 million bales), fully three times more than at the second-leading port of Mobile. The city also boasted a number of Federal buildings, including the New Orleans Mint, a branch of the United States Mint, and the U.S. Custom House.[4]

Louisiana voted to secede from the Union on January 22, 1861. On January 29, the Secession Convention reconvened in New Orleans (it had earlier met in Baton Rouge) and passed an ordinance that allowed Federal employees to remain in their posts, but as employees of the state of Louisiana. In March, Louisiana ratified the Constitution of the Confederate States. The New Orleans Mint was seized; it was used during 1861 to produce Confederate coinage, particularly half-dollars. Since the dies were not changed, these are indistinguishable from 1861-O (the raised O indicating New Orleans) halves minted by the U.S. government. (Using a different reverse die, an unknown number of true Confederate half-dollars were minted, before the silver bullion ran out. See New Orleans Mint.)

New Orleans soon became a major source of troops, armament, and supplies to the Confederate States Army. Among the early responders to the call for troops was the "Washington Artillery," a pre-war militia artillery company that later formed the nucleus of a battalion in the Army of Northern Virginia. In January 1862, men from the free black community of New Orleans formed a regiment of Confederate soldiers called the Louisiana Native Guard. Although they were denied battle participation, the Confederates used the Guard to defend various entrenchments around New Orleans. Several area residents soon rose to prominence in the Confederate States Army, including P.G.T. Beauregard, Braxton Bragg, Albert G. Blanchard, and Harry T. Hays, the commander of the famed Louisiana Tigers infantry brigade which included a large contingent of Irish American New Orleanians.

The city was initially the site of a Confederate States Navy ordnance depot. New Orleans shipfitters produced some innovative warships, including the CSS Manassas (an early ironclad), as well as two submarines (the Bayou St. John submarine and the Pioneer) which did not see action before the fall of the city. The Confederate Navy actively defended the lower reaches of the Mississippi River, during the Battle of the Head of Passes.

Early in the Civil War, New Orleans became a prime target for the Union Army and Navy. The U.S. War Department planned a major attack to seize control of the city and its vital port, to choke off a major source of income and supplies for the fledgling Confederacy.

Fall of New Orleans[edit]

The political and commercial importance of New Orleans, as well as its strategic position, marked it out as the objective of a Union expedition soon after the opening of the Civil War. Captain David Farragut was selected by the Union government for the command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron in January 1862. The four heavy ships of his squadron (none of them armored) were, with many difficulties, brought to the Gulf Coast and the Lower Mississippi River. Around them assembled nineteen smaller vessels (mostly gunboats) and a flotilla of twenty mortar boats under Commander David Dixon Porter.

The main defenses of the Mississippi River consisted of two permanent forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, along with numerous small auxiliary fortifications. The two forts were of masonry and brick construction, armed with heavy rifled guns as well as smoothbores and located on either river bank to command long stretches of the river and the surrounding flats. In addition, the Confederates had some improvised ironclads and gunboats, large and small, but these were outnumbered and outgunned by the Union Navy fleet.

On April 16, after elaborate reconnaissance, the Union's fleet steamed into position below the forts and prepared for the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip. On April 18, the mortar boats opened fire. Their shells fell with great accuracy, and although one of the boats was sunk by counter-fire and two more were disabled, Fort Jackson was seriously damaged. However, the defenses were by no means crippled, even after a second bombardment on April 19. A formidable obstacle to the advance of the Union main fleet was a boom between the forts, designed to detain vessels under close fire if they attempted to run past. Gunboats were repeatedly sent at night to endeavor to destroy the barrier, but they had little success. US Navy bombardment of the forts continued, disabling only a few Confederate guns. The gunners of Fort Jackson were under cover and limited in their ability to respond.

At last, on the night of April 23, the gunboats Pinola and Itasca ran in and opened a gap in the boom. At 2:00 a.m. on April 24, the fleet weighed anchor, Farragut in the corvette Hartford leading. After a severe conflict at close quarters with the forts and ironclads and fire rafts of the defense, almost all the Union fleet (except the mortar boats) forced its way past. The ships soon steamed upriver past the Chalmette batteries, the final significant Confederate defensive works protecting New Orleans from a sea-based attack.

At noon on April 25, Farragut anchored in front of the prized city. Forts Jackson and St. Philip, isolated and continuously bombarded by the mortar boats, surrendered on April 28. Soon afterwards, the infantry portion of the combined arms expedition marched into New Orleans and occupied the city without further resistance, resulting in the capture of New Orleans.[5]

New Orleans had been captured without a battle in the city itself and so it was spared the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South. It retains a historical flavor, with a wealth of 19th-century structures far beyond the early colonial city boundaries of the French Quarter.

The city was in Confederate hands for 455 days.

New Orleans under Union Army[edit]

The Federal commander, Major General Benjamin Butler, soon subjected New Orleans to martial law that was widely reported as an affront in the Southern press. He was accused of many acts that offended the Rebels' sentiments, such as the seizure of $800,000 that had been deposited in the office of the Dutch consul. Butler was nicknamed "The Beast," or "Spoons Butler" (the latter arising from reportd of silverware looted from local homes by some Union troops, although there is no evidence that Butler himself was personally involved). Butler ordered the inscription "The Union Must and Shall Be Preserved" to be carved into the base of the celebrated equestrian statue of General Andrew Jackson, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans, in Jackson Square which the white secccessionist population disliked intensely.

Arriving federal troops saw New Orleans, still covered with smoke from its burned warehouses and smoldering docks. They witnessed the hostility of the multitudes of unemployed white men and how the richer and influential citizens encouraged it, particularly the women.[6] The occupiers saw the Confederacy's largest city's strange streets crowded with people, going around in aimless confusion.[7] Above the general tumult, as the troops entered the streets, could be heard the loud strains of "Bonny Blue Flag," and other secession songs.[7]

As troops debarked from the transports, some were ordered to load the muskets in readiness for any emergency that might arise.[7] Initially, many troops on their arms and to further insure their safety, were issued very strict orders against leaving the quarters for any purpose.[7] The enforcement of military discipline was strict and few felt the local whites could be trusted, and the soldiers were liable at any moment to have to fight for their lives. The men knew they were in a hostile city and little temptation to leave quarters.[8] Beginning at once, their main duties became police and provost guard duty and the distribution of food to the starving citizens.[9] As the federal troops began to appear in public, and travel about on their duties, the bitter hatred of the local white secessionists manifested in numerous ways from disgust looks to vehement verbal attacks. Despite this defiance, the Rebel sympathizers did not attempt any acts of personal violence against the regiment's members.[10]

Occupying units found it took great discipline to adhere to Butler's strict orders for his soldiers as well as for the citizens.[9] Butler ordered all officers to never appear on the streets alone or without their side arms, all troops must pass through the streets in silence taking no offence to insults and threats, and if any violence was attempted must simply arrest the offenders.[9] It was an ordeal of temper and of discipline punctuated by rumors of an uprising by the locals and of Lovell's army returning to recapture the city.[9][note 1] These wise and humane restrictions were often very galling to the pride of the men and under repeated provocation, resentment sometimes got the better of prudence, and the loyal soldiers became exasperated.[10] This resulted in a period of unease during which, night after night the troops slept on their arms, in readiness for instant action.[6] As the occupation continued, they went quietly about their appointed duty, and presently concluded that while they remained in the city, they were relatively safe.[11]

Police and provost duty was the troops' first service as Butler wanted to reestablish law and order quickly. In the organization of police districts, there was commandant of a district, and each captain was assigned to a subdistrict, the soldiers taking the place of the city police, which Butler had disbanded.[12] Large details were made each morning to protect public and private property, to seize concealed arms, and arrest suspicious and disorderly persons.[12]

Butler was very active in rebuilding the city and soon realized he could use the telegraph lines in and about the city for the benefit of his military operations.[13] These were in a disarray and the Confederates, before evacuation, had destroyed or secreted the apparatus of the telegraph offices, cut wires, and done all they could to make the lines inoperative.[14] Butler began to select men from his forces for special service running the telegraph system. Needing a practical and capable telegrapher for the system superintendent, he asked his regimental commanders for such a man, and found the 8th Vermont's Quarter Master Sergeant J. Elliot Smith[note 2] fitting.[16] On Saturday, May 17, Smith was commissioned a lieutenant on Butler's staff and charged with of putting all the city's telegraph lines and of the fire alarm telegraph in order at the earliest possible moment. A young man of ability and energy, he began in earnest. Allowed a detail 40 men to assist him, Smith chose his operators and assistants and taught them practical telegraphy. Soon, Smith had the lines working to all points occupied by Butler's troops.[16]

Initially, local white citizens showed their hostility by closing stores and other public places to the federal troops, but economic necessity overrode their attitude, and they soon reopened their businesses. At first, local white merchants demanded coin or Confederate money. This behavior ceased when Rebel forces failed to return, and they realized that the U.S. government was not leaving. Local traders soon accepted U.S. currency.[17][note 3]

The occupiers gradually saw that the white male population's sentiments were not as spiteful as that of the women who never missed a chance to insult and abuse them. Wearing small Confederate flags conspicuously on their dresses, or waving them in their hands in public places, they would rise and leave a street car if a Union officer entered it. .[18] To avoid meeting soldiers on the sidewalk, they would step into the street. All this hostility and evil treatment the 8th bore with patience winning Butler's approval. It finally cme to a head when a woman spat in the faces of two Federal officers who were quietly walking along the street. In response, Butler issued the famous General Order No. 28 which caused such actions to cease.[18]

This order became notorious to the white secessionist residents. It was also repeated in the Lost Cause mythology in schools throughout the former confederacfy. It stated that if any woman should insult or show contempt for any Federal officer or soldier, she shall be regarded and shall be held liable to be treated as a "woman of the town plying her avocation," a common prostitute. That order provoked storms of protests both in the North and the South as well as abroad, particularly in England and France.

Among Butler's other acts cited as controversial was the June hanging of William Mumford, a pro-Confederacy man who had torn down the US flag over the New Orleans Mint, against Union orders. He also imprisoned a large number of uncooperative citizens. Despite these, Butler's administration had benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and his massive cleanup efforts made it unusually healthy by 19th century standards. However, the international furor over Butler's acts helped fuel his removal from command of the Department of the Gulf on December 17, 1862.

Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks later assumed command at New Orleans. Under Banks, relationships between the troops and citizens improved, but the scars left by the Lost Cause's depiction of Butler's administration lingered for decades. Federal troops continued to occupy the city well after the war through the early part of Reconstruction.

Civil War heritage[edit]

A number of significant structures and buildings associated with the Civil War still stand in New Orleans, and vestiges of the city's defenses are evident downriver, as well as upriver at Camp Parapet.

On Camp Street, Louisiana's Civil War Museum at Confederate Memorial Hall Museum, founded in 1891 by war veterans, boasts the second-largest collection of Confederate military artifacts in the country, after Richmond's Museum of the Confederacy.

Notable New Orleans people of the Confederate military[edit]

- P.G.T. Beauregard, Confederate general and inventor

- Judah P. Benjamin, United States Senator, Confederate Attorney General, Secretary of War and Secretary of State

- Albert G. Blanchard, Confederate general

- Harry T. Hays, Confederate general

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ Lovell wrote to the Confederate War Department, that he made formal offer to the mayor and to prominent citizens, to return "and not leave as long as one brick remained upon another" if they desired. Despite their open hostility to U.S. federal authorities, they, however, "urged decidedly that it be not done," [9]

- ^ Smith, of Montpelier, was a brother the 8th's Quartermaster and after the war had a career as the superintendent of the fire alarm telegraph in New York city.[15]

- ^ Carpenter noted an instance when the 8th Vermont's Quartermaster ran into a boyhood friend who had moved to the city. This Vermont native’s secessionist feeling was so strong that he refused to renew the friendship while the man was wearing his uniform[17]

Citations

- ^ US Census Bureau (2022).

- ^ Johnson (1999), pp. 2, 6.

- ^ Rightor (1900), pp. 417–462.

- ^ a b Benedict (1886), p. 87.

- ^ a b c d Carpenter (1886), p. 34.

- ^ Benedict (1886), p. 87; Carpenter (1886), p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e Benedict (1886), p. 88.

- ^ a b Carpenter (1886), p. 35.

- ^ Carpenter (1886), p. 36.

- ^ a b Benedict (1886), p. 88; Carpenter (1886), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Benedict (1886), p. 89; Carpenter (1886), p. 37.

- ^ Benedict (1886), p. 89; Carpenter (1886), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Benedict (1886), p. 89.

- ^ a b Benedict (1886), pp. 88–89; Carpenter (1886), pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Carpenter (1886), p. 38.

- ^ a b Carpenter (1886), p. 39.

Sources

- Benedict, George Grenville (1886). "The Eighth Regiment". Vermont in the Civil War: A History of the Part Taken by the Vermont Soldiers and Sailors in the War for the Union, 1861-5 (pdf). Vol. II. Burlington, VT: Free Press Association. pp. 80–181. LCCN 02015600. OCLC 301252961. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Carpenter, George N. (1886). History of the Eighth Regiment Vermont Volunteers. 1861-1865 (pdf). Civil War unit histories: Union -- New England. Vol. 8. Boston, MA: Press of Deland & Barta. p. 420. LCCN 02015654. OCLC 547285. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Johnson, Walter (1999). Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (pdf). ACLS Fellows' Publications. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 2, 6. ISBN 978-0-674-03915-5. OCLC 54644159. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- Rightor, Henry (1900). Standard history of New Orleans, Louisiana (pdf). Chicago, IL: The Lewis Publishing Company. pp. 417–462. OCLC 902936037. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - US Census Bureau (October 4, 2022). "1860 Census: Population of the United States". Census.gov. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - U.S. Navy Department (1904). West Gulf Blockading Squadron (February 21, 1862 - July 14, 1862). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies. Vol. XVIII. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 131. OCLC 857196196.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links[edit]

- New Orleans Civil War photo album

- Confederate Memorial Hall museum

- "The Washington Artillery, 5th Company, at the Battle of Perryville"—Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

- Online exhibit about the Civil War at Louisiana State Museum

Further reading[edit]

- Grace King: New Orleans, the Place and the People (1895)

- John Smith Kendall: History of New Orleans (1922)

- Clara Solomon and Elliott Ashkenazi (ed.), The Civil War diary of Clara Solomon : Growing up in New Orleans, 1861-1862. Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press (1995) ISBN 0-8071-1968-7.

- Jean-Charles Houzeau, My Passage at the New Orleans Tribune: A Memoir of the Civil War Era. Louisiana State University Press (2001) ISBN 0-8071-2689-6.

- Albert Gaius Hills and Gary L. Dyson (ed.), "A Civil War Correspondent in New Orleans, the Journals and Reports of Albert Gaius Hills of the Boston Journal." McFarland and Company, Inc.(2013) ISBN 978-0-7864-7193-5.