Patterson Park

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Patterson Park | |

|---|---|

Patterson Park in October | |

| |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Coordinates | 39°17′16″N 76°34′43″W / 39.28778°N 76.57861°W[1][2] |

| Created | 1827 |

Patterson Park is an urban park in Southeast Baltimore, Maryland, United States, adjacent to the neighborhoods of Canton, Highlandtown, Patterson Park, and Butchers Hill. It is bordered by East Baltimore Street, Eastern Avenue, South Patterson Park Avenue, and South Linwood Avenue. The Patterson Park extension lies to the east of the main park, and is bordered by East Pratt Street, South Ellwood Avenue, and Eastern Avenue.

Patterson Park was established in 1827 and named for William Patterson (1752–1835). The park consists of open fields of grass, large trees, paved walkways, historic battle sites, a lake, playgrounds, athletic fields, a swimming pool, an ice skating rink and other signature attractions and buildings.[3] At 137 acres (0.55 km2), Patterson Park is not the city's largest park; however, it is nicknamed "Best Backyard in Baltimore."[4]

Attractions and activities[edit]

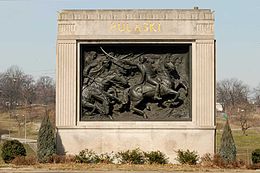

Patterson Park has four main entrances at each corner. Its notable attractions include the boat lake (where fishing is permitted), the marble fountain, the Pulaski Monument, and the Patterson Park Observatory[5][6] The Patterson Park Observatory was built in 1891 as an observation tower for viewing the city and is still open to visitors.[7] The park is also home to the Virginia S. Baker Recreation Center.[8][9]

The park has smooth pathways suitable for biking and jogging. The sports fields are open for use to anyone who wants to play a game, and there are public tennis courts as well.[4][10] There are two playgrounds for children[11] as well as a fenced-in dog park.[12] There is a swimming pool open during the summer[10] and an ice skating rink that operates during winter.[13] From spring to early autumn, several festivals are held in the park.[14] The neighborhood surrounding the park is part of an innovative urban renewal campaign by the city and neighborhood leaders.[15]

Nature[edit]

There are no heavily forested areas of Patterson Park; however, there are plenty of open spaces. The boat lake, reconstructed in 2001 and set for a small renovation in 2022, is inhabited mostly by mallard ducks and nesting Green Heron, but its avian visitors include American Coots and Wood Ducks. Great Blue Heron and Black-crowned Night-Heron are occasionally seen on the lake. There are also fish, frogs, and turtles in the lake.

History[edit]

The high ground at the northwest corner of Patterson Park, called Hampstead Hill, was the key defensive position for U.S. forces against British ground forces in the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812. The redoubt was known as Rodgers Bastion, or Sheppard's Bastion, and was the centerpiece of the earthen line dug to defend the eastern approach to Baltimore, from the outer harbor in Canton north to Belair Road. On September 13, 1814, the day after the Battle of North Point, some 4,300 British troops advanced north on North Point Road, then west along the Philadelphia Road toward Baltimore, forcing U.S. troops to retreat to the defensive line. When the British began probing actions, the American line was defended by 100 cannon and more than 10,000 troops. The American defenses were far stronger than anticipated, and U.S. defenders at Fort McHenry successfully stopped British naval forces from advancing close enough to lend artillery support, and British attempts to flank the defense were countered. Thus, before dawn on September 14, 1814, British commander Colonel Arthur Brooke decided the land campaign was a lost cause, and ordered the retreat back to the ships, and the United States was thus victorious in the Battle of Baltimore.[16][17][18]

William Patterson (d. 1835), a Baltimore merchant, donated 5 acres (20,000 m2) to the city for a public walk in 1827, and the city purchased 29 acres (120,000 m2) additional from the Patterson family in 1860.[19] Additions and improvements to the park made after 1859 were funded through the city's "park tax" on its streetcars, which was initially set at 20% of the fare.[20] During the Civil War, the site was used as a Union troop encampment. Additional purchases in later years increased the park size to its present 137 acres (0.55 km2).

Several public accommodations at the park such as the swimming pools, picnic pavilions, and playgrounds were managed as "separate but equal" until they were desegregated in 1956.[21] The park is included in the Baltimore National Heritage Area.[22]

On October 10, 1962, President John F. Kennedy visited Baltimore and landed in his helicopter at the park and took an open top car to the 5th Regiment Armory.[23] He was in town prior to the midterm elections to stump for the Democratic ticket.

Patterson Park Observatory[edit]

The 60-foot (18 m) Observatory, previously known as the Pagoda, was designed in 1890 and completed in 1892 by Charles H. Latrobe who was the general superintendent and engineer under the Park Commission, led along with architect George A. Frederick, who also designed Baltimore City Hall.[24] It was designed as a people's lookout tower with an Asian motif, inspired by Latrobe's fascination with the East.[25] The Observatory was designated as a Baltimore City Landmark in 1982.[26]

References[edit]

- ^ "Patterson Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. September 12, 1979. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "Patterson Park". GeoNames.org. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Harnik, Peter (2002), The Best Backyard in Baltimore (PDF), Washington, DC: The Trust for Public Land Center for City Park Excellence, retrieved March 30, 2016

- ^ a b Collins, Dan (December 18, 2008). "Patterson Park: Best backyard in Baltimore". Washington Examiner. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Almaguer 2006, p. 37, 42, 111.

- ^ "Friends of Patterson Park: What's In a Name?". Friends of Patterson Park. July 9, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Barbara Haddock (February 28, 2014). "Patterson Park Pagoda: Asian influence in Southeast Baltimore". The Baltimore Sun. ISSN 1943-9504. OCLC 244481759. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Almaguer, Tim (2006). Baltimore's Patterson Park. Images of America series. Tim Almaguer on behalf of the Friends of Patterson Park. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-7385-4365-9. LCCN 2006931585. OCLC 76893485. OL 7902041M – via Google Books.

- ^ "Virginia Baker Recreation Center". pattersonpark.com. Friends of Patterson Park. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Kelly, Jacques (August 7, 2015). "Patterson Park buzzes with activity in the summer". The Baltimore Sun. ISSN 1943-9504. OCLC 244481759. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Places in the Park: Playgrounds". pattersonpark.com. Friends of Patterson Park. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Patterson Park opens new dog park". www.wbaltv.com. WBAL-TV Baltimore. December 17, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Salinas, Sara (June 17, 2015). "Patterson Park redesign would eliminate Mimi DiPietro ice rink". Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Community Events". pattersonpark.com. Friends of Patterson Park. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Patterson Park". www.cityparksalliance.org. City Parks Alliance. 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Alden, Henry Mills, ed. (March 1864). "Scenes in the War of 1812". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Vol. 28. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers. pp. 433–449. hdl:2027/njp.32101064075532. ISSN 0361-8277. OCLC 818988304 – via Google Books.

- ^ Young, Kevin (September 1, 2005). Written at Fort Meade, Md.. "The Battle of Baltimore Sept. 12 to 15, 1814". Soundoff!. Baltimore: Patuxent Publishing and Baltimore Sun Media Group. Archived from the original on December 25, 2010.

- ^ Jensen, Brennen (September 22, 1999). "1812 Overtures: The New Battle of Baltimore Is Reminding Americans About the City's Finest Star-Spangled Hour". City Paper. Baltimore. ISSN 0740-3410. OCLC 9930226. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012.

- ^ Almaguer 2006, p. 9, 29.

- ^ Farrell, Michael R. (1992). The History of Baltimore's Streetcars. With additional material by Herbert H. Harwood, Jr. and Andrew S. Blumberg. Sykesville, Md.: Greenberg Publishing Co. pp. 4–6, 23, 139–40. ISBN 978-0-8977-8283-8. LCCN 92008474. OCLC 25548091. OL 1707017M – via Google Books.

- ^ Almaguer 2006, p. 68.

- ^ "Baltimore National Heritage Area Map" (PDF). City of Baltimore. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "Kennedy Visits Patterson Park in '62". GhostsOfBaltimore.org. November 12, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ Lantz, Emily Emerson (March 14, 1920). "Designer of City Hall, Still Hale and Hearty, Tells of His Long Career". The Sun. Baltimore. p. 8B. ISSN 1930-8965. OCLC 7909813.

- ^ Kelly, Jacques (April 25, 2002). "Patterson Park pagoda, good as new". The Sun. Baltimore. p. 3T. ISSN 2573-2536. OCLC 1076792972.

- ^ Patterson Park Observatory Landmark Designation Report (PDF) (Report). City of Baltimore. September 1971. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

External links[edit]

- The Friends of Patterson Park

- Patterson Park – City of Baltimore

- Patterson Park Audubon Center

- Patterson Park Pagoda at Explore Baltimore Heritage