Royal Pioneer Corps

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Royal Pioneer Corps | |

|---|---|

Cap badge of the corps | |

| Active | 1917–1921 (as Labour Corps) 1939–1993 |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Role | Light engineering tasks |

| Garrison/HQ | Cuddington, Cheshire |

| Motto(s) | Labor omnia vincit |

| March | Pioneer Corps |

The Royal Pioneer Corps was a British Army combatant corps used for light engineering tasks. It was formed in 1939, and amalgamated into the Royal Logistic Corps in 1993. Pioneer units performed a wide variety of tasks in all theatres of war, including full infantry, mine clearance, guarding bases, laying prefabricated track on beaches, and effecting various logistical operations. With the Royal Engineers they constructed airfields and roads and erected bridges; they constructed the Mulberry Harbour and laid the Pipe Line Under the Ocean (PLUTO).

Predecessors[edit]

The first record of pioneers in a British army goes back to 1346 at Calais where the pay and muster rolls of the English Garrison show pay records for pioneers.[1] Traditionally, there was a designated pioneer for each company in a regiment; these were the ancestors of the current assault pioneers. In about 1750, it was proposed that a Corps of Pioneers be formed. Nothing came of this for nearly one hundred years, until the Army Works Corps was established during the Crimean War in 1854.[1]

The Labour Corps was formed in 1917 during the First World War,[2] during which it employed 325,000 British troops, alongside 98,000 Chinese, 10,000 Africans and at least 300,000 other labourers in separate units such as the Chinese Labour Corps and Maltese Labour Corps.[1]

History[edit]

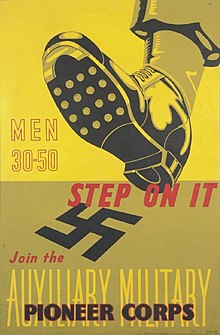

In September 1939, a number of infantry and cavalry reservists were formed into Works Labour Companies, which were soon made the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps (AMPC); a Labour Directorate was created to control all labour force matters. A large number of Pioneers served in France with the British Expeditionary Force.[3]

During the Battle of France in May 1940, No. 5 Group AMPC commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Donald Dean VC, were engaged in labouring tasks in the Doullens area, near Amiens, when the group were threatened by the advancing Germans. After requisitioning a train, and following a fire-fight with the leading German units, the Group were able to reach Boulogne-sur-Mer. Here Dean was ordered to help establish a defensive perimeter around the town.[4] On 23 May, the Germans attacked in earnest; in fierce fighting at their barricades, the pioneers destroyed one tank by igniting petrol underneath it. The pioneers were the last to fall back from the perimeter and most were evacuated from the harbour.[5] Further to the south, on 18 May, an infantry brigade was improvised from several AMPC Companies under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. H. Diggle. Known as "Digforce", the brigade became part of Beauman Division and fought in defence of the Andelle and Béthune rivers on 8 June 1940 against the 5th and 7th Panzer Divisions. Digforce brigade and thousands of other BEF Pioneers were evacuated to England in Operation Aerial.[6] An unknown number of AMPC troops were killed when the HMT Lancastria was sunk off St Nazaire on 17 June.[7]

On 22 November 1940, the name AMPC was changed to Pioneer Corps.[8] In March 1941, James Scully was awarded the George Cross. Corps members have won thirteen George Medals and many other lesser awards.[9]

A total of 23 pioneer companies took part in the Normandy landings.[10] The novelist Alexander Baron served in one of these Beach Groups and later included some of his experiences in his novels From the City From the Plough and The Human Kind; he also wrote a radio play about the experience of being stranded on a craft attempting to land supplies on the beaches of Normandy. Nos. 85 and 149 Companies, Pioneer Corps served with the 6th Beach Group assisting the units landing on Sword Beach on D Day, 6 June 1944.[11]

On 28 November 1946, in recognition of their performance during the Second World War, King George VI decreed that the Pioneer Corps should have the distinction "Royal" added to its title.[10]

In April 1993, following the Options for Change review, the Royal Pioneer Corps was joined with the Royal Corps of Transport, the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, the Army Catering Corps, and the Postal and Courier Service of the Royal Engineers to form the Royal Logistic Corps.[12]

The last unit to retain the "pioneer" title, 23 Pioneer Regiment, Royal Logistic Corps, which saw action in operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, was disbanded in 2014. A 'farewell' parade was held on 26 September at St David's Barracks, MoD Bicester in Oxfordshire; it was attended by Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester.[13] The regiment's ceremonial axes will continue to be used by the Royal Logistic Corps.[14]

Recruitment[edit]

In the early part of the Second World War, the Pioneer Corps was the only British military unit in which enemy aliens could serve.[15] Thousands of German and Austrian nationals joined the Pioneer Corps to assist Allied war efforts and the liberation of their home countries. They typically were Jews and political opponents of the Nazi Regime who had fled to Britain, including film production designer Ken Adam, writers George Clare and Arthur Koestler, and publisher Robert Maxwell.[16]

Later, some members of Pioneer Corps—often dubbed "The King's Most Loyal Enemy Aliens"—transferred to serve in various fighting units. Some were recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to serve as secret agents and were parachuted behind enemy lines.[17]

Serving as a German or Austrian national in the British forces was especially dangerous because, in case of being taken captive, there was a high probability of being executed as a traitor by the Germans. Still, the number of German-born Jews joining the British forces was exceptionally high; by the end of the war, one in seven Jewish refugees from Germany had joined the British forces. Their knowledge of the German language and customs proved particularly useful; many served in the administration of the British occupation army in Germany and Austria after the war.[18]

The Pioneer Corps also recruited from among Spanish exiles after the Spanish Civil War. No.1 Spanish Company was formed.[19]

It has wrongly been said at various times that British conscientious objectors were sometimes ordered into the Pioneer Corps by Conscientious Objection Tribunals in the Second World War; the error may have arisen from a misunderstanding of a misleadingly drafted question in the House of Lords on 22 July 1941 and a reply by Lord Croft, joint Under-Secretary of State for War, that was not expressed with the clarity that might have been expected. The War Office was asked about "British conscientious objectors who have been ordered by the Tribunals to undertake service with the Pioneer Corps", whereas the Tribunals had no power to make such an order; the only power they had relating to conscientious objectors in the armed forces was to order non-combatant military service, meaning call-up in most cases to the Non-Combatant Corps, or occasionally to the Royal Army Medical Corps; the Pioneer Corps, as a combatant unit, was by definition excluded. In his reply, Lord Croft referred to "conscientious objectors ordered for attachment to the Pioneer Corps", only obliquely correcting the language of the question. To spell it out in full, what Lord Croft meant was "conscientious objectors ordered by the Tribunals to serve in the Non-Combatant Corps and then, as members of the NCC, attached at certain times and for certain purposes to the Pioneer Corps".[20]

Colonels Commandant[edit]

Colonels Commandant of the corps were:[21]

- 1940–1948: F.M. The Rt Hon George Milne, 1st Baron Milne of Salonika

- ?1940–1950: Lt-Col. (Hon. Brig.) John Bartlett Hillary

- 1950–1961: Gen. Sir Frank Ernest Wallace Simpson

- 1961–1968: Lt-Gen. Sir John Cowley

- 1968–1976: Lt-Gen. Sir J. Noel Thomas

- 1976–1981: Gen. Sir William Gerald Hugh Beach

- 1981–1983: Gen. Sir George Leslie Conroy Cooper

- 1983–1986: Brig. Alan Frederick Mutch

- 1986–1987: Maj-Gen. John James Stibbon

- 1987: Brig. Frederick John Lucas

- Maj-Gen. Geoffrey William Field (to Royal Logistic Corps, 1993)

- 1993: Royal Pioneer Corps merged with Royal Corps of Transport, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Army Catering Corps, and the Postal and Courier Service of the Royal Engineers to form the Royal Logistic Corps

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "The Pioneer: History". Royal Pioneer Corps Association. p. 1. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Baker, Chris. "The Labour Corps of 1917-1918". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Julian (2009). Dunkirk: Retreat to Victory. London: Pan Books. p. 169. ISBN 978-0330437967.

- ^ Thompson 2009, p. 178

- ^ *Ellis, L. F. (1954) The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. J. R. M. Butler (ed.). HMSO. London pp. 280–282

- ^ "The Pioneer: The Lancastria Story". Royal Pioneer Corps Association. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "The Pioneer: History". Royal Pioneer Corps Association. p. 2. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "The Pioneer: Honours and awards". Royal Pioneer Corps Association. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ a b "The Pioneer: History". Royal Pioneer Corps Association. p. 3. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "Invisible Ink: No 83 - Alexander Baron". The Independent. 26 June 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ "The Royal Logistic Corps and Forming Corps". The Royal Logistic Corps Museum. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Disbanded 23 Pioneer Regiment in final parade". BBC News. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Howes, Capt. (Adj. 23 Pioneer Regt.). "THE PIONEER NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2014 - Final Parade of 23 Pioneer Regiment RLC". issuu.com. Royal Pioneer Corps Association. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "House of Lords Questions - Aliens in the Pioneer Corps". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 22 July 1941. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Robert Maxwell". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ "Walter Freud – from Loughborough College to the Special Operations Executive". Loughborough History and Heritage Network. 29 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ National Geographic documentary Churchill's German Army

- ^ Whitehead, Jonathan (2021). Spanish Republicans and the Second World War: Republic Across the Mountains. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1399004510.

- ^ "House of Lords question: conscientious objectors". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 22 July 1941. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Royal Pioneer Corps". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

Further reading[edit]

- Fry, Helen, The King's Most Loyal Enemy Aliens - Germans who fought for Britain in the Second World War, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7509-4701-5

- Smith, L, Forgotten Voices of the Holocaust, Ebury Press, 2005, ISBN 0-09-189825-0

External links[edit]