SMS Karlsruhe

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Karlsruhe |

| Namesake | Karlsruhe |

| Builder | Germaniawerft, Kiel |

| Laid down | 1911 |

| Launched | 11 November 1912 |

| Commissioned | 15 January 1914 |

| Fate | Sank 4 November 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Karlsruhe-class cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 142.2 m (466 ft 6 in) |

| Beam | 13.7 m (44 ft 11 in)1 |

| Draft | 5.38 m (17 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 29.3 kn (54.3 km/h; 33.7 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

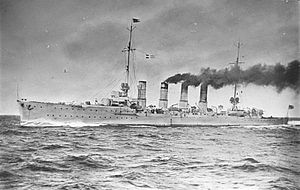

SMS Karlsruhe was a light cruiser of the Karlsruhe class built by the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). She had one sister ship, SMS Rostock; the ships were very similar to the previous Magdeburg-class cruisers. The ship was laid down in 1911, launched in November 1912, and completed by January 1914. Armed with twelve 10.5 cm SK L/45 guns, Karlsruhe had a top speed of 28.5 knots (52.8 km/h; 32.8 mph), which allowed her to escape from British cruisers during her career.

After her commissioning, Karlsruhe was assigned to overseas duties in the Caribbean. She arrived in the area in July 1914, days before the outbreak of World War I. Once the war began, she armed the passenger liner SS Kronprinz Wilhelm, but while the ships were transferring equipment, British ships located them and pursued Karlsruhe. Her superior speed allowed her to escape, after which she operated off the northeastern coast of Brazil. Here, she captured or sank sixteen ships. While en route to attack the shipping lanes to Barbados on 4 November 1914, a spontaneous internal explosion destroyed the ship and killed the majority of the crew. The survivors used one of Karlsruhe's colliers to return to Germany in December 1914.

Design[edit]

Karlsruhe was 142.2 meters (466 ft 6 in) long overall and had a beam of 13.7 m (44 ft 11 in) and a draft of 5.38 m (17 ft 8 in) forward. She displaced 6,191 t (6,093 long tons; 6,824 short tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of Marine steam turbines driving two 3.5-meter (11 ft) propellers. They were designed to give 26,000 shaft horsepower (19,000 kW), but reached 37,885 shp (28,251 kW) in service. These were powered by twelve coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers and two oil-fired double-ended boilers. These gave the ship a top speed of 28.5 knots (52.8 km/h; 32.8 mph). Karlsruhe carried 1,300 t (1,300 long tons) of coal, and an additional 200 t (200 long tons) of fuel oil that gave her a range of approximately 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Karlsruhe had a crew of 18 officers and 355 enlisted men.[1]

The ship was armed with a main battery of twelve 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, eight were located amidships, four on either side, and two were side by side aft.[2] The guns had a maximum elevation of 30 degrees, which allowed them to engage targets out to 12,700 m (41,700 ft).[3] They were supplied with 1,800 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. She was also equipped with a pair of 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes with five torpedoes submerged in the hull on the broadside. She could also carry 120 mines. The ship was protected by a waterline armored belt that was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick amidships. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides, and the deck was covered with up to 60 mm thick armor plate.[1]

Service history[edit]

Karlsruhe was ordered under the contract name "Ersatz Seeadler" and was laid down at the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel on 21 September 1911. She was christened by Karl Siegrist, the mayor of Karlsruhe, and launched on 11 November 1912, after which fitting-out work commenced. Builder's trials began in mid-December 1913, followed by full sea trials with the navy, which revealed that the ship consumed coal at a prodigious rate. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 15 January 1914. Karlsruhe's first commanding officer was Fregattenkapitän (FK—Frigate Captain) Fritz Lüdecke. Following her commissioning in January 1914, Karlsruhe conducted further trials that lasted until June. She then returned to the yard for modifications in an unsuccessful attempt to improve the situation. The navy intended to send Karlsruhe to the East American Station, where she was to replace the light cruiser Bremen, but owing to the delays in her completion, the cruiser Dresden was sent instead. Once Karlsruhe was ready, she departed Kiel on 14 June.[1][4]

On 1 July, Karlsruhe reached Saint Thomas in the Danish West Indies; there the ship received news of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo three days before. The ship then proceeded to Port-au-Prince, Haiti to protect German nationals during a period of civil unrest in the city from 5 to 9 July. Karlsruhe was then scheduled to meet Dresden in Veracruz, Mexico, but further unrest in Haiti forced the cancellation of the meeting. On 27 July, Karlsruhe and Dresden finally met and exchanged commanders. FK Erich Köhler came aboard Karlsruhe and Lüdecke was to take Dresden back to Germany, though this was not to be carried out. Karlsruhe was to have gone to Veracruz and then to the opening ceremonies of the Panama Canal, but Köhler decided against this since the July Crisis over Ferdinand's assassination was at its peak, and there were numerous British and French warships already present for the celebration. Instead, he took his ship to Havana, Cuba, where he remained for two days. On 30 July, Karlsruhe left the port, initially keeping close to shore before proceeding to the isolated Cay Sal Bank in the Straits of Florida in an attempt to evade any observers. To throw any pursuers off his trail, Köhler broadcast a message in the open that he intended to call at Tampico, Mexico on 4 August. The British armored cruiser HMS Berwick was in the area, and Köhler had the opportunity to arm the passenger ship SS Kronprinz Wilhelm as an auxiliary cruiser in the event of war, so Karlsruhe steamed east into the open Atlantic Ocean.[5]

World War I[edit]

On the night of 3/4 August, Karlsruhe received word of the state of war between Germany and France, and the greatly increased risk of conflict with Britain. Karlsruhe's standing orders in the event of war were to conduct a commerce raiding campaign against British merchant traffic.[5] Dresden was still present in the region at the outbreak of World War I at the end of July,[6] which complicated the British attempt to hunt down the German cruisers. To hunt down Karlsruhe, Dresden, and any merchant ships she might arm as auxiliary cruisers, the Royal Navy deployed five cruiser squadrons, the most powerful were those commanded by Rear Admiral Christopher Craddock and Rear Admiral Archibald Stoddart. The British were forced to disperse their ships to cover the areas in which the two German cruisers, and any auxiliary cruisers they might arm, could operate.[7]

On 6 August, Karlsruhe rendezvoused with Kronprinz Wilhelm about 120 nmi (220 km; 140 mi) north of Watling Island. Karlsruhe was in the process of transferring guns and equipment to the liner when Craddock, in his flagship HMS Suffolk, appeared to the south.[8] The Germans had only managed to transfer two 8.8 cm guns, a machine gun, and some sailors by the time Suffolk arrived.[6] The two ships quickly departed in different directions; Suffolk followed Karlsruhe and other cruisers were ordered to intercept her. Karlsruhe's faster speed allowed her to quickly outpace Craddock, but at 20:15, Bristol joined the pursuit and briefly fired on the German cruiser.[8] The German gunners scored two hits on Bristol during the short engagement, forcing the latter to slow down.[5] Karlsruhe turned east and again used her high speed to evade the British ships. The British failed to relocate her, and by 9 August, Karlsruhe reached Puerto Rico with only 12 tons of coal in her bunkers.[8] There, she coaled from a HAPAG freighter in the port before departing for the coast of Brazil, since merchant traffic was heavier there.[9] The area was also not as heavily patrolled by the British.[10]

While on the way, Karlsruhe stopped in Willemstad in Curaçao to take on more coal and oil. After reaching the northern coast of Brazil, she sank her first British steamship on 18 August. Over the course of 21–23 August, the ship went to Maraca island south of the mouth of the Amazon river to replenish her coal stocks from a German steamship. The German prewar plans had arranged for German merchant vessels to act as colliers to support commerce raiding cruisers by operating in neutral waters at pre-planned meeting points. The voraciousness of Karlsruhe's boilers nevertheless significantly reduced her radius of action. In addition to making use of German colliers, Köhler frequently took coal from the ships he captured. He also kept one or two prizes to assist in the search for targets. Karlsruhe patrolled the eastern coast of South America, as far south as La Plata, Argentina; in the course of these operations, she sank or captured at least sixteen merchant ships. These merchantmen, fifteen British ships and one Dutch vessel, totaled 72,805 gross register tons (GRT). Köhler then decided to move to another area, as remaining in one area would increase his chances of being tracked down by the British. He turned his ship toward the West Indies to attack Barbados and Fort-de-France and the shipping lanes between Barbados and Trinidad.[10][11]

As Karlsruhe steamed to Barbados on the night of 4 November, a spontaneous internal explosion destroyed the ship at approximately 18:30. The hull was split in half; the bow section quickly sank and took with it Köhler and most of the crew. The stern remained afloat long enough for 146 of the ship's crew to escape onto the attending colliers, the Hamburg Süd liner SS Rio Negro and the captured British steamer SS Indrani. At 18:57, the stern also sank. Commander Studt, the senior surviving officer, took charge and placed all of his men aboard Rio Negro. He scuttled Indrani and steamed north for Iceland. The ship used the cover of a major storm to slip through the British blockade of the North Sea, and put in at Ålesund, Norway. Rio Negro then returned to Germany on 6 December. The Admiralstab, unaware of the loss of Karlsruhe, coincidentally radioed the ship to order her to return to Germany.[12] Germany kept the loss of the ship a secret, and the British continued searching for her until they learned of her fate in March 1915. As a result, eleven British cruisers were tied up, searching for the cruiser, for almost six months after she had been destroyed.[10][11] Köhler's widow christened the cruiser Karlsruhe, the third to bear the name, at her launching in August 1927.[13]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Gröner, p. 109.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 160.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 140.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 84.

- ^ a b Halpern, p. 78.

- ^ Bennett, p. 74–75.

- ^ a b c Bennett, p. 75.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c Halpern, p. 79.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 85.

- ^ Bennett, p. 131.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 89.

References[edit]

- Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics. ISBN 978-1-84415-300-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 5. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0456-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

11°07′00″N 55°25′00″W / 11.1167°N 55.4167°W