Second Battle of St Albans

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Second Battle of St Albans | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

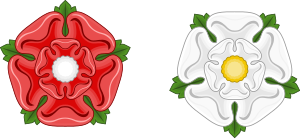

| Part of the Wars of the Roses | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 15,000 men | c. 10,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,916 killed, mostly Yorkists | |||||||

Location of the battle within England | |||||||

The Second Battle of St Albans was fought on 17 February 1461 during the Wars of the Roses in St Albans, Hertfordshire, England (the First Battle of St Albans had been fought in 1455).

The army of the Yorkist faction, under the Earl of Warwick, attempted to bar the road to London north of the town. The rival Lancastrian army used a wide outflanking manoeuvre to take Warwick by surprise, cut him off from London and drive his army from the field. The victors also released the feeble King Henry VI, who had been Warwick's prisoner, from his captivity, but they ultimately failed to take advantage of their victory.

Background[edit]

The Wars of the Roses were fought between the supporters of two branches of the Plantagenet dynasty: the House of Lancaster, represented by the mentally-unstable King Henry VI, and those of the rival House of York. Richard of York quarrelled with several of Henry's court during the late 1440s and the early 1450s. He was respected as a soldier and administrator and was believed by his own supporters to have a better claim to the throne than Henry. York and his friends rebelled in 1455. At the First Battle of St Albans, York gained a victory but that did not resolve the causes of the conflict. After attempts at reconciliation, fighting resumed in 1459. At the Battle of Northampton in 1460, Richard of York's nephew, the Earl of Warwick, defeated a Lancastrian army and captured King Henry, who had taken no part.

York returned to London from exile in Ireland and attempted to claim the throne but his supporters were not prepared to go so far. Instead, an agreement was reached, the Act of Accord by which York or his heirs were to become king after Henry's death. That agreement disinherited Henry's young son, Edward of Westminster. Henry's wife, Margaret of Anjou, refused to accept the Act of Accord and took Edward to Scotland to gain support there. York's rivals and enemies raised an army in the north of England. York and his brother-in-law, the Earl of Salisbury (Warwick's father), led an army to the north late in 1460 to counter these threats but they underestimated the Lancastrians. At the Battle of Wakefield, the Yorkist army was destroyed; York. Salisbury and York's second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, were killed or executed after the battle.

Campaign[edit]

The victorious Lancastrian army began advancing south towards London. It was led by comparatively young nobles such as the Duke of Somerset, the Earl of Northumberland and Lord Clifford, whose fathers had been killed by York and Warwick at the First Battle of St Albans. The army contained substantial contingents from the West Country and the Scottish Borders and largely subsisted on plunder as they marched south.

The death of Richard of York left his 18-year-old son, Edward, Earl of March, as the Yorkist claimant for the throne. He led one Yorkist army in the Welsh Marches while Warwick led another in London and the south-east. Naturally, they intended to combine their forces to face Margaret's army, but Edward was delayed by the need to confront another Lancastrian army from Wales, which was led by Jasper Tudor and his father, Owen Tudor. On 2 February, Edward defeated Tudor's army at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross.

Warwick, with the captive King Henry in his train, meanwhile moved to block Queen Margaret's army's route to London. He took up position north of St Albans astride the main road from the north (the ancient Roman road known as Watling Street), where he set up several fixed defences, including cannon and obstacles such as caltrops and pavises studded with spikes.[1] Part of his defences used the ancient Belgic earthwork known as Beech Bottom Dyke. Warwick's forces were divided into three "Battles",[n 1] as was customary at the time. He himself led the Main Battle in the centre. The Duke of Norfolk led the Forward (or Vaward) Battle on the right and Warwick's brother John Neville commanded the Rear Battle on the left.

Although strong, Warwick's lines faced north only. Margaret knew of Warwick's dispositions, probably through Sir Henry Lovelace, the steward of Warwick's own household. Lovelace had been captured by the Lancastrians at Wakefield but had been spared from execution and released and believed that he had been offered the vacant Earldom of Kent as a reward for betraying Warwick.[2] Late on 16 February, Margaret's army swerved sharply west and captured the town of Dunstable. About 200 local people under the town butcher tried to resist them but were easily dispersed. Warwick's "scourers" (scouts and patrols and foraging parties) failed to detect the move.

Battle[edit]

From Dunstable, Margaret's forces moved south-east at night towards St Albans. The leading Lancastrian forces attacked the town shortly after dawn. Storming up the hill past the Abbey, they were confronted by Yorkist archers in the town centre who shot at them from the house windows. The first attack was repulsed. As they regrouped at the ford across the River Ver, the Lancastrian commanders sought another route into the town. That was found, and a second attack was launched along the line of Folly Lane and Catherine Street. The second attack met with no opposition, and the Yorkist archers in the town were now outflanked. They continued to fight house to house, however, and were not finally overcome for several hours.[3]

Having gained the town itself, the Lancastrians turned north towards John Neville's Rear Battle, positioned on Bernards Heath. In the damp conditions,[n 2] many of the Yorkists' cannon and handguns failed to fire, as their powder was dampened. Warwick found it difficult to extricate his other units from their fortifications and tonturn them about to face the Lancastrians and so the Yorkist battles straggled into action one by one, instead of in co-ordinated fashion. The Rear Battle, attempting to reinforce the defenders of the town, was engaged and dispersed. It has been suggested that the Kentish contingent in the Yorkist army under Lovelace defected at that point, which caused further confusion in the Yorkist ranks,[3][4] but later historians suggest that Lovelace's role as 'a scapegoat'[5] was created by Warwick as a facesaving excuse to mask his own 'total mismanagement' of the battle.[5] Certainly, Lovelace was not attainted after the Battle of Towton.

By late afternoon, the Lancastrians were attacking north-east out of St Albans to engage the Yorkist Main and Vaward battles under Warwick and Norfolk. As dusk set in, which would have been in the very early evening at this time of year and in the poor weather, Warwick realised that his men were outnumbered and increasingly demoralised, and he withdrew with his remaining forces (about 4,000 men) to Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire.[3]

One annalist estimated the total dead at 2,000 men.[6] An anonymous chronicler gave the exact figure of 1,916.[7]

Aftermath[edit]

As the Yorkists retreated, they left behind the bemused King Henry, who is supposed to have spent the battle sitting and singing under a tree. Two knights (the elderly Lord Bonville and Sir Thomas Kyriell, a veteran leader of the Hundred Years' War) had sworn to let him come to no harm and remained with him throughout. The next morning, Margaret asked her son, the seven-year-old Edward of Westminster, how, not whether, the two Knights of the Garter were to die. Edward, thus prompted, sent them to be beheaded.[8] John Neville had been captured but was spared execution, as the Duke of Somerset feared that his own younger brother, who was in Yorkist hands, might be executed in reprisal.[9]

Henry knighted the young Prince Edward, who in turn knighted thirty Lancastrian leaders. One was Andrew Trollope, an experienced captain who had deserted the Yorkists at the Battle of Ludford Bridge in 1459 and was reckoned by many to have planned the Lancastrian victories at Wakefield and St Albans. At St Albans, he had injured his foot stepping on one of Warwick's caltrops, but he nevertheless claimed to have killed fifteen Yorkists.[9] William Tailboys is also mentioned as having been knighted by Henry VI after the battle.[10]

Although Margaret and her army could now march unopposed on to London, they did not do so. The Lancastrian army's reputation for pillage caused the Londoners to bar the gates. That, in turn, caused Margaret to hesitate, as did the news of Edward of March's victory at Mortimer's Cross. The Lancastrians fell back through Dunstable and lost many Scots and Borderers, who deserted and returned home with the plunder that they had already gathered. Edward of March and Warwick entered London on 2 March, and Edward was quickly proclaimed King Edward IV of England. Within a few weeks, he had confirmed his hold on the throne with a decisive victory at the Battle of Towton. Perhaps the most significant person to be killed at the Battle of St Albans, at least in t or its dynastic results, was John Grey of Groby, whose widow, Elizabeth Woodville, married Edward IV in 1464.[11]

550th anniversary commemoration[edit]

To commemorate the 550th anniversary year of the battle, the Battlefields Trust hosted a conference on the battle on 26–27 February 2011, near the battle site. The conference featured authentic combat recreations by the Medieval Siege Society and a guided tour of the battlefield and culminated in a Requiem Mass for the fallen at St Saviour's Church, conducted by Father Peter Wadsworth.[12]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Battaglia" in Rome were an ancestor. During the English Civil War, "battalia", or battle lines, led to the formation in British Army as 'battalion'.

- ^ Although a number of secondary sources refer to the snow, recent research has shown that there is no reference to snow in any of the primary sources. It is now believed that the mention of snow came about from confusion with Towton, six weeks later, when snowy weather is clearly attested. See Burley et al, p73

References[edit]

- ^ Michael Hicks, The Wars of the Roses: 1455-1485, (Osprey, 2003), 37.

- ^ Anthony Goodman, The Wars of the Roses, (Dorset Press:New York 1981), 127.

- ^ a b c S. G. Shaw (1815) History of Verulam and St. Alban's Pages 65-70

- ^ Warner (1975), p.83

- ^ a b Gillingham, J. (London: 1983 repr) The Wars of the Roses London: 1983 repr. p. 126

- ^ Giles 1845, p. lxxxv.

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 243.

- ^ Ralph A Griffiths, The Reign of King Henry VI University of California Press, 1981. p. 872.

- ^ a b Rowse 1966, p. 143.

- ^ John A. Wagner Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Roses, 263

- ^ Charles Ross, Edward IV, (University of California Press, 1974), 85.

- ^ "St Albans History". www.stalbanshistory.org.

Sources[edit]

- Giles, J.A., ed. (1845). The Chronicles of the White Rose of York. London: James Bohn.

- Goodman, Anthony (1981). Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452–97. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-0728-0.

- Philip Warner, British Battlefields: the South, Fontana, 1975

- Rowse, A.L. (1966). Bosworth Field & the Wars of the Roses. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-85326-691-4.

Further reading[edit]

- Burley, Peter; Elliott, Michael & Watson, Harvey (2007). The Battles of St Albans. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-569-9.

- Cron, B.M. (1999). "Margaret of Anjou and the Lancastrian March on London, 1461" (PDF). The Ricardian. 11 (147): 590–615. ISSN 0048-8267.