Second circle of hell

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

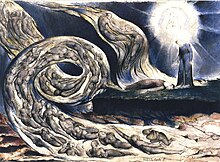

The second circle of hell is depicted in Dante Alighieri's 14th-century poem Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy. Inferno tells the story of Dante's journey through a vision of the Christian hell ordered into nine circles corresponding to classifications of sin; the second circle represents the sin of lust, where the lustful are punished by being buffeted within an endless tempest.

The circle of lust introduces Dante's depiction of King Minos, the judge of hell; this portrayal derives from the role of Minos in the Greek underworld in the works of Virgil and Homer. Dante also depicts a number of historical and mythological figures within the second circle, although chief among these are Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, murdered lovers whose story was well-known in Dante's time. Malatesta and da Rimini have since been the focus of academic interpretation and the inspiration for other works of art.

Punishment of the sinners in the second circle of hell is an example of Dantean contrapasso. Inspired jointly by the biblical Old Testament and the works of ancient Roman writers, contrapasso is a recurring theme in the Divine Comedy, in which a soul's fate in the afterlife mirrors the sins committed in life; here the restless, unreasoning nature of lust results in souls cast about in a restless, unreasoning wind.

Synopsis[edit]

Inferno is the first section of Dante Alighieri's three-part poem Commedia, often known as the Divine Comedy. Written in the early 14th century, the work's three sections depict Dante being guided through the Christian concepts of hell (Inferno), purgatory (Purgatorio), and heaven (Paradiso).[1] Inferno depicts a vision of hell divided into nine concentric circles, each home to souls guilty of a particular class of sin.[2]

Led by his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, Dante enters the second circle of hell in Inferno's Canto V. Before entering the circle proper they encounter Minos, the mythological king of the Minoan civilization. Minos judges each soul entering hell and determines which circle they are destined for, curling his tail around his body a number of times corresponding to the circle they are to be punished in.[3] Passing beyond Minos, Dante is shown the souls of the lustful being buffeted in a swirling wind—he surmises that as they were driven in life not by reason but by instinct, in death they are similarly scattered by an unreasoning force.[4]

Within the tempest of souls, Virgil points out notable individuals to Dante, beginning with the Lydian ruler Semiramis, the Carthaginian queen Dido, and Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra, as well as the legendary figures Achilles, Paris, Helen of Troy, and Tristan. Dante's attention is drawn by two souls who are carried along together; addressing them directly he learns from one that they are Francesca da Rimini and her lover Paolo Malatesta. As da Rimini describes the adultery that condemned them, Dante is overcome with pity and faints; on waking, he is in hell's third circle.[5]

Background[edit]

For neither doom nor judge nor house may any lack in death:

The seeker Minos shakes the urn, and ever summoneth

The hushed-ones' court, and learns men's lives and what against them stands.

—Aeneid, Book VI, lines 430–432[6]

Dante's use of King Minos as the judge of the underworld is based on the character's appearance in Book VI of Virgil's Aeneid, where he is portrayed as a "solemn and awe-inspiring adjudicator" in life.[7] In the works of Virgil and of Homer, Minos is shown becoming the judge of the Greek underworld after his own death, influencing his role in the Divine Comedy.[8] The role played by Minos in Inferno conflates elements of Virgil's Minos with his depiction of Rhadamanthus, brother of Minos, elsewhere in the Aeneid. Rhadamanthus is also a judge of the dead, although unlike Minos, who presides over a single court, Rhadamanthus is described by Virgil as flogging the dead, compelling them to confession.[9] In describing Minos and his judgments, Dante accurately employed contemporary legal and judicial terminology, and quotations from the canto have been found as marginalia in Bolognese legal registers from the early 14th century.[10]

The pair of lovers encountered in the second circle of hell, Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, are historical figures roughly contemporaneous with Dante. A member of the da Polenta family, the rulers of Ravenna, da Rimini was married to Paolo's brother Giovanni Malatesta, of the ruling family of Rimini, by political arrangement. The affair between da Rimini and Paolo was discovered by Giovanni, who murdered them both in what became a widely-known case in Italy at the time. Dante was supported as an artist by the patronage of da Rimini's nephew Guido II da Polenta between the years of 1317 and 1320.[11][12] Dante gives little direct detail of the story in Canto V, assuming that his readers are already familiar with the events.[13]

Analysis[edit]

Dante's depiction of hell is one of order, unlike contemporary representations which, according to scholar Robin Kirkpatrick, were "pictured as chaos, violence and ugliness".[14] Kirkpatrick draws a contrast between Dante's poetry and the frescoes of Giotto in Padua's Scrovegni Chapel. Dante's orderly hell is a representation of the structured universe created by God, one which forces its sinners to use "intelligence and understanding" to contemplate their purpose.[15] The nine-fold subdivision of hell is influenced by the Ptolemaic model of cosmology, which similarly divided the universe into nine concentric spheres.[16]

The second circle of hell sees the use of contrapasso, a theme throughout the Divine Comedy.[17] Derived from the Latin contra ("in return") and pati ("to suffer"), contrapasso is the concept of suffering in the afterlife being a reflection of the sins committed in life. This notion derives both from biblical sources such as the books of Deuteronomy and Leviticus, as well the classical writers Virgil and Seneca the Younger; Seneca's Hercules Furens expresses the notion that "quod quisque fecit patitur", or "what each has done, he suffers".[17] In the second circle of hell, this is manifested as an eternal storm which buffets souls in its wake; as the lustful in life acted "without reason", so too are their souls tossed about without reason.[18] Literature professor Wallace Fowlie has additionally characterised the punishment as one of restlessness, writing that, like the souls in the tempest, "sexual desire [...] can never be satisfied, never at rest".[19]

Writer Paul W. Kroll compared some of Dante's work in Canto V with the work of 6th-century poet Boethius, noting the similarity between da Rimini's statement that "no sorrow is great than to recall, in misery, the happy times" with the words of Boethius in De Consolatione Philosophiae: "for in all adversity of fortune the most unhappy kind of misfortune is to have once been happy".[20] The depiction of da Rimini and Malatesta within the second circle inspired later works of art celebrating what has been seen as a tragic tale of doomed lovers; 19th-century French sculptor Auguste Rodin depicts the pair in The Kiss, whilst Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky based his 1877 tone poem Francesca da Rimini on the incident.[21] The damnation of da Rimini and Malatesta has drawn also academic attention, often focussing on the circumstance of their affair's beginning—da Rimini describes the pair being inspired by the Arthurian tale of Galehaut bringing together Lancelot and Guinevere as the pretext to their own affair. Writers Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian, in their book Love and its Critics: From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden, quote a range of interpretation on this theme. Both Barbara Reynolds and Edoardo Sanguineti cite the couple's flimsy use of poetry as a justification for adultery as their true moral failing, while Mary-Kay Gamel points to the tragic end of the Arthurian story as foreshadowing their demise: "if [da Rimini] had read further, she would have discovered how grave [...] were the consequences of Lancelot and Guinevere's illicit love".[22]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Albertini 1998, p. xii.

- ^ Albertini 1998, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2013, p. 21.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Albertini 1998, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Morris 2008, Book VI.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2015, p. 104.

- ^ Fowlie 1981, p. 43.

- ^ Barolini 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Crisafi & Lombardi 2019, p. 71.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Albertini 1998, p. 160.

- ^ Fowlie 1981, p. 45.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2013, p. 163.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2013, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Albertini 1998, p. 149.

- ^ a b Lansing 2010, p. 220.

- ^ Musa 1995, pp. 53 & 120.

- ^ Fowlie 1981, p. 44.

- ^ Kroll 2020, p. 118.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2015, p. 98.

- ^ Bryson & Movsesian 2017, pp. 321–322.

References[edit]

- Alighieri, Dante (1998). Albertini, Stefano (ed.). Inferno. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-853-26787-1.

- Alighieri, Dante (2013). Kirkpatrick, Robin (ed.). Inferno. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-141-39354-4.

- Barolini, Teodolinda (2006). Dante and the Origins of Italian Literary Culture. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-823-22705-1.

- Bryson, Michael; Movsesian, Arpi (2017). Love and its Critics: From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton's Eden. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-350-6.

- Crisafi, Nicolò; Lombardi, Elena (2019). "Lust and the Law: Reading and Witnessing in Inferno V". Ethics, Politics and Justice in Dante. pp. 63–39. in Gaimari & Keen (2019)

- Fowlie, Wallace (1981). A Reading of Dante's Inferno. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-25888-1.

- Kirkpatrick, Robin (2015). "Massacre, Miserere and Martyrdom". Vertical Readings in Dante's Comedy. pp. 97–118. in Corbett & Webb (2015)

- Kroll, Paul W. (2020). "On Some Verses of Li Bo". At the Shores of the Sky: Asian Studies for Albert Hoffstädt. pp. 113–128. in Kroll & Silk (2020)

- Lansing, Richard, ed. (2010). The Dante Encyclopaedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-84972-5.

- Virgil (2008). Morris, William (ed.). The Æneids of Virgil Done into English Verse. Candler Press. ISBN 978-1-409-76359-8.

- Corbett, George; Webb, Heather Mariah, eds. (2015). Vertical Readings in Dante's Comedy. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-172-4.

- Gaimari, Giulia; Keen, Catherine, eds. (2019). Ethics, Politics and Justice in Dante. UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-78735-227-8.

- Kroll, Paul W.; Silk, Jonathan A., eds. (2020). At the Shores of the Sky: Asian Studies for Albert Hoffstädt. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-43820-0.

- Musa, Mark, ed. (1995). Dante's Inferno: The Indiana Critical Edition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01240-1.