Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Francesco di Giorgio Martini |

| Year | c. 1478–82 |

| Medium | Walnut, beech, rosewood, oak and fruitwoods in walnut base |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has on display a complete studio from the Palazzo ducale di Gubbio. Consisting of period woodwork from late 15th century Italy, the studio was commissioned for Federico da Montefeltro.

History[edit]

As the Renaissance swept through Italy, the cultural movement caused the rebirth and development of numerous artistic styles. Among these concepts was the development of the studiolo, a secluded room intended to allow for quiet study and meditation. These rooms contained, either physically or in the form of artistic depictions, books, tomes, scientific instruments, and other symbols of knowledge, particularly if they were associated with Classical Greece or Rome.[1] Elaborately decorated with paintings and intricate woodwork, studioli became a sign of status and sophistication for the nobility, court officials, and artists of the Italian Renaissance.[2] The small rooms would later be known as a hallmark of the Quattrocento, the art movement encompassing the first 100 years of the Italian Renaissance.[3][1]

The studiolo housed in the Met was commissioned by Duke Federico da Montefeltro, a major geopolitical force in North-Central Italy during his lifetime. In addition for being a capable military leader, Federico was noted for being a prolific patron of the arts; his activities, such as the employing of artists, architects, and writers resulted in him being given the moniker "the Light of Italy". Federico commissioned his first studiolo at his palace in Urbino, the House of Montefeltro's traditional seat of power; this feat was replicated when in 1478 he ordered the design and installation of a studiolo in an old palace he was rebuilding in Gubbio, which was under his control. The new room was designed by Sienese artist Francesco di Giorgio Martini, who also worked on a number of other projects for da Montefeltro, including the construction of the Palazzo ducale di Gubbio (where the studiolo was installed) itself.[4] Martini's design was executed (under his supervision) by two Tuscan brothers famed for their work with interior woodworking, Giuliano and Benedetto da Maiano. The entire room was constructed in the da Maiano's workshop in Florence, after which it was transported to Gubbio for installation.[3][5][1]

The studiolo remained in the Palazzo at Gubbio until 1874, when it was disassembled and moved to a villa in Frascati. The room was then purchased by a German art dealer and moved to Venice. The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired the work in 1939 and had the studiolo shipped to New York City, where it was re-assembled between 1939 and 1941.[3][1]

Description[edit]

The studiolo consists of a number of wood panels fitted together. These panels are divided into twelve consecutive sections, surrounding the room on all sides. The artists' use of intarsia (inlaid wood) to render realistic, two-dimensional images of latticework cabinets, drawers, and siding is representative of the rediscovery of linear perspective in mid-15th century Italy.[5] The extensive use of intarsia is particularly noticeable in the room, as the inlaid wood forms the contrast used to create the illusion of depth. In addition, paint and more intarsia is used to depict objects that a leader of Renaissance period would be expected to have in their study. Objects depicted include measuring instruments, a tropical bird in a cage, armor, books, and musical instruments.[3] The studiolo's coffered wood ceiling is adorned with carved geometric designs. The room originally contained several paintings, but these were removed from the studiolo in the 17th century. Three windows provide lighting for the room.[2][1]

A phrase, done in gold-on-blue frieze along the upper panels of the room, reads;

"You see the eternal nurselings of the venerable mother, men pre-eminent in learning and genius, How they fall with bared neck before …knee. Honored loyalty prevails over justice, and no one Repents having yielded to his foster mother."[3]

Gallery[edit]

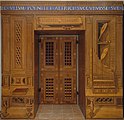

- Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio

- Various cabinets, doors open or ajar, filled with objects of note.

- Entrance wall of the studio

- Close-up of an illusory depiction of a bench

- An armillary sphere, books, and a quadrant depicted through the use of intarsia

- Federico da Montefeltro's personal coat of arms, done in inlay in the soffit of the entrance doorway

- Depiction of a parrot in a cage

- A pipe organ and a lyre

- A collection of musical and measuring instruments

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Peck, Amelia, James Parker, William Rieder, Olga Raggio, Mary B. Shepard, Annie-Christine Daskalakis Mathews, Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide, Wolfram Koeppe, Joan R. Mertens, Alfreda Murck, and Wen C. Fong (1996). Period Rooms in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Print. New York, New York. pp. 41-47

- ^ a b Kirkbride, Robert (November 2008). Architecture and Memory: The Renaissance Studioli of Federico da Montefeltro. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231512275.

- ^ a b c d e "Studiolo from the Ducal Palace". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ^ Weller, Allen Stuart (1943). Francesco di Giorgio, 1439–1501. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–44.

- ^ a b Art, National Gallery of. "Italian Renaissance Learning Resources - The National Gallery of Art". www.italianrenaissanceresources.com. Retrieved 2018-07-15.