Temple of Baalshamin

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

معبد بعل شمين | |

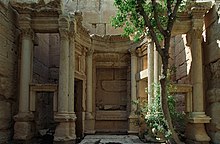

The Temple of Baalshamin in 2010 | |

| Location | Palmyra, Syria |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°33′12″N 38°16′12″E / 34.553401°N 38.269941°E |

| Type | Temple |

| History | |

| Material | Stone |

| Founded | 131 AD |

| Cultures | Palmyrene |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1954–1956 |

| Condition | Restored, August 2015 |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Inaccessible (in a war zone) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Part of | Site of Palmyra |

| Reference no. | 23 |

| Region | Arab States |

| Endangered | 2013–2015 (destroyed) |

The Temple of Baalshamin was an ancient temple in the city of Palmyra, Syria, dedicated to the Canaanite sky deity Baalshamin. The temple's earliest phase dates to the late 2nd century BC;[1] its altar was built in 115 AD,[2] and the temple was substantially rebuilt in 131 AD. The temple would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire in a campaign against the temples of the East made by Maternus Cynegius, Praetorian Prefect of Oriens, between 25 May 385 to 19 March 388.[3] With the spreading of Christianity in the region in the 5th century AD, the temple was converted to a church.[4]

In 1864, French photographer and naval officer Louis Vignes was the first to photograph the temple following his expedition to the Dead Sea under the sponsorship of the Duc du Luynes.[5]

It was one of the most complete ancient structures in Palmyra.[4] In 1980, UNESCO designated the temple as a World Heritage Site.

In 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant demolished the Temple of Baalshamin after capturing Palmyra during the Syrian Civil War.

Architectural style[edit]

The temple was originally a part of an extensive precinct of three courtyards and represented a fusion of ancient Syrian and Roman architectural styles. The temple's proportions and the capitals of its columns were Roman in inspiration, while the elements above the architrave and the side windows followed the Syrian tradition. The highly stylized acanthus patterns of the Corinthian orders also indicated an Egyptian influence.[4] The temple had a six-column pronaos with traces of corbels and an interior which was modelled on the classical cella. The side walls were decorated with pilasters.

Inscription and dedication[edit]

An inscription written in Greek and Palmyrene, on the column bracket that supported the bust of the temple's benefactor, the Palmyrene official Male Agrippa, attested the temple was built in 131 AD.[6] The inscription was dedicated by the Senate of Palmyra to honor Male Agrippa for building the temple, which was dedicated to Baalshamin, the Semitic god of the heavens, to commemorate the Roman Emperor Hadrian's visit to Palmyra around 129 AD.[7] The translated inscription is:

The Senate and the people have made this statue to Male Agrippa, son of Yarhai, son of Lishamsh Raai, who, being secretary for a second time when the divine Hadrian came here, gave oil to the citizens, and to the troops and the strangers that came with him, taking care of their encampment. And he built the temple, the vestibule, and the entire decoration, at his own expense, to Baal Shamin and Durahlun.[6]

Damage[edit]

Parts of the temple were damaged to some extent by bombings in 2013, during the Syrian Civil War.[8] The southeastern corner of the temple wall was damaged further by looters who made two openings to steal the furniture of the adjacent guesthouse.[8]

Destruction[edit]

In May 2015, Palmyra was captured by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), a terrorist group with a history of destroying ancient religious structures. Shortly after, ISIL reportedly claimed that it did not intend to demolish the buildings at Palmyra's World Heritage Site, but stated that it would destroy any artifact it deemed "polytheistic" or "pagan".[10] On 23 August 2015 (or earlier in July, according to some reports), ISIL militants detonated a large quantity of explosives inside the Temple of Baalshamin, completely destroying the building.[11][12] The temple's destruction was announced by the head of the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, Maamoun Abdulkarim.[11] Photographs of the placement of the explosives, the explosion itself and the remnants of the temple subsequently appeared on social media.[13] UNESCO described the willful destruction of the temple as a "war crime".[14][15] The destruction was independently verified by a French Pléiades satellite, which photographed the pile of rubble a few days later.[16]

After the temple's destruction, the Institute for Digital Archaeology announced plans to establish a digital record of historical sites and artifacts threatened by IS advance.[17][18][19] To accomplish this goal, the IDA, in collaboration with UNESCO, will deploy 5,000 3D cameras to partners in the Middle East.[20] The cameras will be used to capture 3D scans of local ruins and relics.[21][22]

Following the recapture of Palmyra by the Syrian Army in March 2016, director of antiquities Maamoun Abdelkarim stated that the Temple of Baalsahamin, along with the Temple of Bel and the Monumental Arch, will be rebuilt using the surviving remains (anastylosis).[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-19-964667-8. LCCN 2013942192.

- ^ Stoneman, Richard (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. University of Michigan Press. p. 65. ISBN 0472083155.

- ^ Trombley, Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370-529

- ^ a b c Darke, Diana (2010). Syria. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 271. ISBN 978-1841623146.

- ^ France Terpak and Peter Louis Bonfitto. "Louis Vignes". The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra. The Getty Research Institute. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ a b Teixidor, Javier (2015). The Pagan God: Popular Religion in the Greco-Roman Near East. Princeton University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1400871391.

- ^ Romey, Kristin (August 26, 2015). "How Ancient Palmyra, Now in ISIS's Grip, Grew Rich and Powerful". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ a b Ali, Cheikhmous (June 2015). "Palmyra: Heritage Adrift" (PDF). American Schools of Oriental Research. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Islamic State photos 'show Palmyra temple destruction'". BBC News. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Shaheen, Kareem (27 May 2015). "Syria: Isis releases footage of Palmyra ruins intact and 'will not destroy them'". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Palmyra's Baalshamin temple 'blown up by IS'". BBC News. 9 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "IS Destruction of Ancient Syrian Temple Erases Rich History". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 24 August 2015. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "المديرية العامة للآثار والمتاحف" (in Arabic). DGAM.gov.sy. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Staff (24 August 2015). "Director-General Irina Bokova firmly condemns the destruction of Palmyra's ancient temple of Baalshamin, Syria" (Press release). UNESCO. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

The systematic destruction of cultural symbols embodying Syrian cultural diversity reveals the true intent of such attacks, which is to deprive the Syrian people of its knowledge, its identity and history...this destruction is a new war crime

- ^ Shaheen, Kareem (24 August 2015). "Palmyra: destruction of ancient temple is a war crime, says Unesco chief". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (29 August 2015). "Palmyra: Satellite image of IS destruction". BBC News. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ Sean Higgins. "Oxford Deploying 5,000 Modified 3D Cameras to Fight ISIS". sparpointgroup.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ^ "The digital race against IS". BBC Radio 4 "Today" programme. BBC. 28 August 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Rosenfield, Karissa (1 September 2015). "Harvard and Oxford Take On ISIS with Digital Preservation Campaign". Arch Daily. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Mackay, Mairi (31 August 2015). "Indiana Jones with a 3-D camera? Hi-tech fight to save antiquities from ISIS". CNN. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Alanna Martinez (September 2015). "Can 3-D Imaging Save Ancient Art from ISIS?". Observer.

- ^ Martin, Guy (31 August 2015). "How England's Institute Of Digital Archeology Will Preserve The Art Isis Wants to Destroy". Forbes. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Shaheen, Kareem; Graham-Harrison, Emma (27 March 2016). "Syrian regime forces retake 'all of Palmyra' from Isis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016.