The Gumps

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The Gumps | |

|---|---|

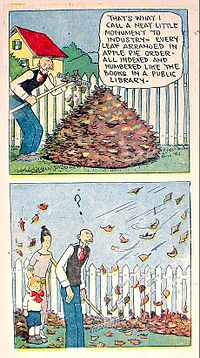

Sidney Smith's The Gumps (September 30, 1923) | |

| Author(s) | Sidney Smith (1917–1935) Gus Edson (1935–1959) |

| Current status/schedule | Ended |

| Launch date | February 12, 1917 |

| End date | October 17, 1959 |

| Syndicate(s) | Chicago Tribune Syndicate |

| Publisher(s) | Charles Scribner's Sons IDW Publishing |

| Genre(s) | Comedy, melodrama |

The Gumps is a comic strip about a middle-class family. It was created by Sidney Smith in 1917, launching a 42-year run in newspapers from February 12, 1917, until October 17, 1959.

According to a 1937 issue of Life, The Gumps was inspired by Andy Wheat, a real-life person Smith met through his brother. "Born forty-seven years ago [i.e., in 1890] in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, Andy Wheat acquired his unusual physiognomy as the result of an infection following the extraction of a tooth, which eventually necessitated the removal of his entire lower jaw. Through Dr. Thomas Smith of Bloomingdale, Illinois, a dentist and a brother of Sidney Smith, Wheat met the cartoonist, who saw in him an ideal comic character. Wheat subsequently had his surname legally changed to "Gump" to match the cartoon character. His wife's name is Min, and he has two children, Chester and Goliath, now living in San Francisco, and an Uncle Bim who lives in Georgia. Gump's home is in Tucson, Arizona, but he also has a farm near his birthplace in Mississippi."[1]

Characters and story[edit]

The Gumps were utterly ordinary: chinless, bombastic blowhard Andy Gump (short for Andrew), who is henpecked by his wife, Min (short for Minerva); their sons Chester and baby Goliath (plus an unnamed daughter in college and an unnamed son in the Navy); wealthy Uncle Bim; and their annoying maid Tilda. They had a cat named Hope and a dog named Buck. The idea was envisioned by Joseph Patterson, editor and publisher of the Chicago Tribune, who was important in the early histories of Little Orphan Annie and other long-run comic strips. Patterson referred to the masses as "gumps" and thought a strip about the domestic lives of ordinary people and their ordinary activities would appeal to the average American newspaper reader. He hired Smith to write and draw the strip, and it was Smith who breathed life into the characters. Smith was the first cartoonist to kill off a regular character: His May 1929 storyline about the death of Mary Gold caused a national sensation.[2]

The Sunday page also included several toppers over the course of the run: Old Doc Yak (Dec 7, 1930 – Feb 25, 1934), Cousin Juniper (Jan 2, 1944–1955) and Grandpa Noah (1955).[3]

Debut[edit]

The Gumps made its debut in an unusual way. Cartoonist Sidney Smith had previously drawn and written Old Doc Yak, a talking-animal strip that sustained only a brief run. The very last Old Doc Yak strip depicted Yak and his family moving out of their house, while wondering who might move into the house next. On Thursday, February 8, 1917, the last panel showed only the empty house. On Monday, February 12, 1917, after the Gumps were introduced in the space formerly occupied by Old Doc Yak, they moved into the house formerly occupied by the Yak family. (Old Doc Yak would reappear as a topper for The Gumps Sunday page from 1930 to 1934.)

The Gumps had a key role in the rise of syndication when Robert R. McCormick and Patterson, who had both been publishing the Chicago Tribune since 1914, planned to launch a tabloid in New York, as comics historian Coulton Waugh explained:

"So originated on June 16, 1919, the Illustrated Daily News, a title which, as too English, was almost at once clipped to Daily News. It was a picture paper, and it was a perfect setting for the newly developed art of the comic strip. The first issue shows but a single strip, The Gumps. It was the almost instant popularity of this famous strip that directly brought national syndication into being. Midwestern and other papers began writing to the Chicago Tribune, which also published The Gumps, requesting to be allowed to use the new comic, and the result was that the heads of the two papers collaborated and founded the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate, which soon was distributing Tribune-News features to every nook and cranny of the country".[4]

Films[edit]

As one of the earliest continuity strips, The Gumps was extremely popular, with newspaper readers anxiously following the convoluted storylines. By 1919, this popularity prompted an interest in film adaptations, and in 1920–21, with writing credited to Smith, animation director Wallace A. Carlson produced and directed more than 50 animated shorts, some no longer than two minutes, for distribution through Paramount.[5]

Between 1923 and 1928, Universal Pictures produced at least four dozen Gumps two-reel comedies starring Joe Murphy (1877–1961), one of the original Keystone Cops, as Andy Gump, Fay Tincher as Min and Jack Morgan as Chester. Many of these shorts were directed by Norman Taurog, later famed as the leading director of Elvis Presley movies.

In the comic strip, Sidney Smith had Andy run for Congress in 1922 and for President in 1924 and in practically every succeeding election, one of the first of many comic strip and cartoon characters to run for office. In 1924, Smith wrote his characters into a novel, Andy Gump: His Life Story, published in Chicago by Reilly & Lee. In 1929, when Smith killed off Mary Gold, she was the first major comic strip character to die, and the Chicago Tribune had to hire extra staff to deal with the constant phone calls and letters from stunned readers.

The strip and its merchandising (toys, games, a popular song, playing cards, food products) made Smith a wealthy man. On his way home from signing a $150,000 a year contract in 1935, he crashed his new Rolls-Royce and died. Patterson replaced Smith with sports cartoonist Gus Edson. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, when actor Martin Landau was a cartoonist, he worked as Edson's assistant on The Gumps, eventually drawing the Sunday strips for Edson.

Radio[edit]

The Gumps launched a craze for continuity strips in newspapers. It also influenced radio and television programming. Radio/TV sitcoms and serialized dramas can all be traced back to The Gumps, as detailed by broadcast historian Elizabeth McLeod in the "Andy Gump to Andy Brown" section of her popular culture essay,[6] and her book, The Original Amos 'n' Andy: Freeman Gosden, Charles Correll, and the 1928–43 Radio Serial (McFarland, 2005).

At the Chicago Tribune's radio station WGN, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll signed on as staffers in 1925. WGN executive Ben McCanna believed that a dramatic serial could work on radio just as it did in newspapers. The Gumps first aired on WGN in 1931, then moved to CBS Radio for a four-year run (1934–1937), produced and directed by Himan Brown with scripts by Irwin Shaw.

In the early programs, Jack Boyle portrayed Andy Gump with Dorothy Denvir as Min, Charles Flynn as their son Chester and Bess Flynn, born 1899 in Tama, Iowa, as Tilda the maid. Flynn scripted for soap operas, including Bachelor's Children, Martha Webster and We, the Abbotts, and she also portrayed the title role on Martha Webster. In 1935, Wilmer Walter played Andy Gump with Agnes Moorehead portraying Min during the last two years of the series when Lester Jay and Jackie Kelk were heard as Chester.[7]

Reprints[edit]

Herb Galewitz assembled a selective compilation of the comic strips for the book, Sidney Smith's The Gumps, published in 1974 by Charles Scribner's Sons. However, the strips in this book were assembled in a slipshod manner with no apparent restoration.

In 2012, IDW's imprint The Library of American Comics announced a new series reprinting daily strips, in the LoAC Essentials. A Gumps volume titled The Saga of Mary Gold (1928–29) was published in March 2013.

Tributes[edit]

A gift from the Tribune management to Smith was a large statue of Andy Gump, which stood on Smith's Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, estate. After Smith died in 1935, the statue was moved to a city park. In 1943, the statue was acquired by the city of Lake Geneva, but it was destroyed in 1967 during a drunken riot. It was replaced with a new statue, which was stolen in 1989 and again replaced. A plaque honoring Smith was also stolen from Lake Geneva in 1952, but it was later found.[8] The statue is currently on display at the Lake Geneva Museum.[9]

Hockey great Gump Worsley, born Lorne Worsley, was nicknamed for his resemblance to Andy Gump.

Jazz musician Min Leibrook, born Wilford Leibrook, received his nickname from Andy Gump's wife, Min.

The town of Bim, West Virginia is named for Uncle Bim Gump.

A bunker on the 16th hole of the Hinsdale Golf Club in Clarendon Hills, IL is shaped in the likeness of Andy Gump.

The surgical removal of the mandible can result in a dysmorphism referred to as the Andy Gump deformity due to his character design apparently lacking a jaw.[10]

References[edit]

- ^ Warner, John L. "Andy Gump in Person", Life, July 12, 1937.

- ^ "Big Deals: Comics' Highest-Profile Moments," Hogan's Alley #7, 1999

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 114, 176, 294. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ Waugh, Coulton. The Comics, 1947.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 29. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Amos 'n' Andy—In Person

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- ^ Roadside America: "Andy Gump Statue."

- ^ Geneva Lake Museum

- ^ Lilly, Gabriela L.; Petrisor, Daniel; Wax, Mark K. (August 2021). "Mandibular rehabilitation: From the Andy Gump deformity to jaw-in-a-day". Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 6 (4): 708–720. doi:10.1002/lio2.595. PMC 8356852. PMID 34401495.

Further reading[edit]

- Harvey, Robert C. The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994. (pp. 60–67).

External links[edit]

- Barnacle Press: The Gumps

- The Gumps at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012.

- Meet the Gumps

- Andy Gump Pinbacks