The Man Who Could Work Miracles (short story)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| "The Man Who Could Work Miracles" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by H. G. Wells | |

| |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre(s) | Science fiction |

| Publication | |

"The Man Who Could Work Miracles" is a British fantasy-comedy short story by H. G. Wells first published in 1898 in The Illustrated London News. It carried the subtitle "A Pantoum in Prose".[1]

The story is an early example of contemporary fantasy (not yet recognized, at the time, as a specific subgenre). In common with later works falling within this definition, the story places a major fantasy premise (a wizard with enormous, virtually unlimited magic power) not in an exotic semi-medieval setting but in the drab routine daily life of suburban London, very familiar to Wells himself.

Plot summary[edit]

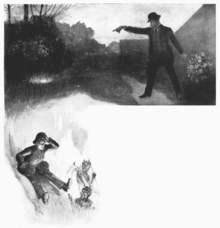

In an English public house, George McWhirter Fotheringay vigorously asserts the impossibility of miracles during an argument. By way of demonstration, Fotheringay commands an oil lamp to flame upside down and it does so, to his own astonishment. His acquaintances think it a trick and quickly dismiss it.

Fotheringay explores his new power. After magically accomplishing his daily chores as an office clerk, Fotheringay quits early to a park to practice further. He encounters a local constable, who is accidentally injured. In the ensuing altercation, Fotheringay unintentionally sends the policeman to Hades; hours later, Fotheringay relocates him safely to San Francisco.

Unnerved by these miracles, Fotheringay attends local Sunday church services. The clergyman, Mr. Maydig, preaches about unnatural occurrences. Fotheringay is deeply moved, and meets Maydig in his manse for advice. After a few petty demonstrations, the minister becomes enthusiastic and suggests that Fotheringay should use these abilities to benefit others. That night they walk the town streets, healing illness and vice and improving public works.

Maydig plans to reform the whole world. He suggests that they could disregard their obligations for the next day if Fotheringay could stop the night altogether. Fotheringay agrees and stops the motion of the Earth. His clumsy wording of the wish causes all objects on Earth to be hurled from the surface with great force. Pandemonium ensues, but Fotheringay miraculously ensures his own safety back on the ground. In fact (though he is not aware of the enormity of what he had done) the whole of humanity except for himself had perished in a single instant.

Fotheringay is unable to return the Earth to its prior state. He repents, and wishes that the power be taken from him and the world restored to a time before he had the power. Fotheringay immediately finds himself back in the public house, discussing miracles with his friends as before, without any recollection of previous events.

The all-knowing narrator thus tells the reader that he or she had died "a year ago" (the story was published in 1897) and was then resurrected - but has no recollection of anything special having happened.

Adaptations[edit]

In 1936, the story was adapted to a film starring Roland Young as Fotheringay. Wells co-wrote the screenplay with Lajos Bíró.[2]

It was first adapted for BBC Radio in 1934 by Laurence Gilliam and broadcast on 4 June that year.[3] It continued to be adapted on several occasions for BBC Radio, including 1956 by Dennis Main Wilson and broadcast on New Year's Day. It starred Tony Hancock as Fotheringay.[4]

The story idea was used as the basis for director Terry Jones's 2015 film Absolutely Anything.[5]

The idea of the world stopping rotating was taken up in 1972 by Lester del Rey, who suggested to three SF writers to write stories based on the assumption that God does it in order to unequivocally prove His existence to all humanity. The three resulting stories were published together under the name "The Day the Sun Stood Still", comprising "A Chapter of Revelation" by Poul Anderson, "Things Which Are Caesar's" by Gordon R. Dickson and "Thomas the Proclaimer" by Robert Silverberg. The three stories share the assumption that – the miracle in this case issuing directly from God in person, rather than from Wells' fumbling human protagonist – care was taken to prevent the disastrous results evident in the original Wells story. The dramatic radio broadcast appearing in the beginning of Silverberg's version indicates that, when writing, he was familiar with the Wells story: "Latest observatory reports confirm that no appreciable momentum effects could be detected as Earth shifted to its present period of rotation. Scientists agree that the world's abrupt slowing on its axis should have produced a global catastrophe leading, perhaps, to the destruction of all life. However, nothing but minor tidal disturbances have been observed so far".[6]

For his part, the Portuguese José Saramago apparently refers to the Wells story in his novel Cain, an irreverent retelling of the Bible, when retelling the episode of God "stopping the sun" in the Book of Joshua (to which the pastor in the Wells story also refers). The very flawed God depicted by Saramago was unable to stop the disastrous effects of stopping the movement of the Earth – so he did not do so, performing just a much simpler and limited miracle which still did the job.

References[edit]

- ^ Maunder, Andrew (22 April 2015). Encyclopedia of the British Short Story. Infobase Learning. ISBN 9781438140704 – via Google Books.

- ^ "BFI Screenonline: Man Who Could Work Miracles, The (1937) Credits". www.screenonline.org.uk.

- ^ Radio Times, Issue 557, 4 June 1934 [1]

- ^ "The Man Who Could Work Miracles". 28 December 1956. p. 18 – via BBC Genome.

- ^ Plumb, Ali. "Terry Jones On His New Sci-Fi Comedy Absolutely Anything". Empire Magazine. Bauer Consumer Media. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Robert Silverberg, "Thomas the Proclaimer", Ch.1

External links[edit]

- The complete short fiction of H. G. Wells at Standard Ebooks

- "The Man Who Could Work Miracles" at Project Gutenberg

"The Man Who Could Work Miracles" public domain audiobook at LibriVox

"The Man Who Could Work Miracles" public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "The Man Who Could Work Miracles" title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- The Man Who Could Work Miracles at IMDb