Thomas Fitzpatrick (trapper)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

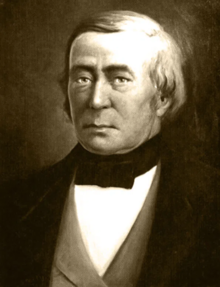

Thomas Fitzpatrick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1799 |

| Died | February 7, 1854 (aged ~55) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Resting place | Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | Irish-American |

| Other names | "Broken Hand" |

| Occupation(s) | Mountain Man, trapper, guide, Indian agent |

| Spouse | Margaret Poisal |

| Children | Friday, Arapaho Chief (unofficially adopted) |

| Relatives | Chief Niwot (wife's maternal uncle) |

Thomas Fitzpatrick (1799 – February 7, 1854) was an American-American fur trader, Indian agent, and mountain man.[1] He trapped for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and the American Fur Company. He was among the first white men to discover South Pass, Wyoming. In 1831, he found and took in a lost Arapaho boy, Friday, who he had schooled in St. Louis, Missouri; Friday became a noted interpreter and peacemaker and leader of a band of Northern Arapaho.

Fitzpatrick was a government guide and also led a wagon train of pioneers to Oregon. He helped negotiate the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851. In the winter of 1853–54, Fitzpatrick went to Washington, D.C., to see after treaties that needed to be approved, but while there he contracted pneumonia and died on February 7, 1854.

He was known as "Broken Hand" after his left hand had been crippled in a firearms accident.[2]

Early life[edit]

Thomas Fitzpatrick was born in County Cavan, Ireland in 1799 to Mary Kieran and Mr. Fitzpatrick. They were a moderately wealthy Catholic family with three boys and four girls. Fitzpatrick received a good education and he left home before the age of 17.[3] He became a sailor and left a ship at New Orleans. From there, he traveled up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri[4] by the winter of 1822–1823.[3]

Trapper[edit]

Andrew Henry and William Henry Ashley announced that they were searching for fur trappers for their company, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company[5] by placing an ad in the Missouri Republican in 1822:

To Enterprising young men: the subscriber wishes to engage one hundred men, to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years.[3]

An experienced fur trapper and trader, Andrew Henry had built Fort Henry a trading post at Yellowstone in 1822.[3] Fitzpatrick went to work for the fur traders, joining the likes of Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, Louis Vasquez, Étienne Provost, and William Lewis Sublette.[5] He survived an attack on the Rocky Mountain Fur Company during the Arikara War of 1823.[5] The Arikara were successful in preventing the trappers from traveling the Missouri River. Needing another route, Fitzpatrick and Jedediah Smith led 15 men to find an overland route over the Rocky Mountains.[6] He re-discovered South Pass, Wyoming in 1824; John Jacob Astor's fur trading expedition of 1811–1812 (led by Robert Stuart) were the first known white party through the South Pass.[3] It became a route through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.[6]

From South Pass, their journey took them into the Green River basin, which was a good source of beaver. Fitzpatrick made a return trip with a large stock of pelts. Fitzpatrick led two horse trains with goods and supplies over South Pass to trade for furs in the Green River area and he managed placement of bands of trappers.[6] The first Rocky Mountain Rendezvous was held on the frontier, which provided entertainment and a means for trappers to trade furs for supplies without traveling to a trading post.[6] In 1830, he became a senior partner of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company with Jim Bridger and others.[5][6]

In 1832, Fitzpatrck rode ahead of the supply train and was chased by a Gros Ventre tribe through the wilderness. The "harrowing" experience is said to have caused him to prematurely gray. He later led a group of allied Native Americans and trappers against the Gros Ventre in the Battle of Pierre's Hole.[6] The Rocky Mountain Fur Company dissolved in 1834 and he was a partner in two fur trading organizations. The American Fur Company bought one of the firms and Fitzpatrick worked for them as a band leader.[6][7]

Father to an Arapaho boy[edit]

In 1831, he found an Arapaho boy who had been separated from his band that had camped with the Atsina (Gros Ventre) along the Cimmaron River in present-day southeastern Colorado.[8][9] A fight had broken out that led to the Arapaho chief being stabbed, and the Atsina chief was killed in retaliation.[9] He found the boy on a Friday, which was the nexus of his name from that point forward. Fitzpatrick took Friday in and enrolled him in a in school St. Louis, Missouri that he attended for two years.[10][11] Fitzpatrick brought Friday along on his trapping journeys in the western frontier.[8] In 1838, Fitzpatrick and Friday met up with a band of Arapaho people. When a woman recognized Friday as her son, Friday returned to his life with the Arapaho.[8] He remained friends with Fitzpatrick until his death in 1854.[11]

Guide & Mexican-American War[edit]

When the fur trade was no longer viable, he became a guide.[12] He shepherded the first two emigrant wagon trains to Oregon, including the Whitman-Spalding Party (1836)[5] and the Bartleson-Bidwell Party (1841).

He was the official guide to John C. Frémont on his 1843 to 1845 expedition.[12] He guided Col. Stephen W. Kearny and his Dragoons along the westward trails in 1845[5] to impress the Native Americans with their howitzers and swords.

He accompanied Kearny's men in their invasion of Mexico in 1846 at the beginning of the Mexican-American War.[13]

Indian Agent[edit]

In 1846, he became an Indian Agent of the Upper Platte and Arkansas River Valleys (a sizeable portion of present-day Colorado),[2][12][14] and was well-respected by Native Americans and white settlers.[2] He negotiated with Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota Sioux of the Central Plains.[6] Fitzpatrick was a negotiator for the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851, at the largest council ever assembled of Native Americans of the Plains.[6] He was a negotiator for the Treaty of Fort Atkinson in July 1853 with the Plains Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche.[2][6]

Marriage[edit]

In November 1849, Fitzpatrick formally married Margaret Poisal, the daughter of a French-Canadian trapper John Poisal and Snake Woman an Arapaho woman.[6][15] She was the niece of Arapaho Chief Land Hand (Chief Niwot).[15] Their son, Andrew Jackson Fitzpatrick, was born in 1850. Virginia Tomasine Fitzpatrick was born in 1854,[16] after her father's death.[6]

Poisal served as an important translator for the Arapaho peoples and often worked alongside Fitzpatrick at important meetings. After his death, Poisal served as the official interpreter for the Arapaho during the Little Arkansas Treaty Council in 1865.[15][17]

Death and legacy[edit]

In the winter of 1853–54, Fitzpatrick went to Washington, D.C., to finalize the Treaty of Fort Atkinson,[6] but while there contracted pneumonia and died on February 7, 1854.[18][14] He was buried in the Congressional Cemetery there.[6]

In 2004, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[1]

In 1970, Broken Hand Peak in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of Colorado was officially named in his honor.[19]

Popular culture[edit]

In the 1966 episode "Hugh Glass Meets the Bear" of the syndicated television series, Death Valley Days, the actor Morgan Woodward was cast as Fitzpatrick. John Alderson played Hugh Glass, who after being mauled by a bear and abandoned by Fitzpatrick crawled two hundred miles to civilization. Victor French was cast as Louis Baptiste, with Tris Coffin as Major Andrew Henry.[20][21]

Fitzpatrick appears to have been confused or conflated with John S. Fitzgerald, who, according to the Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography, was actually the one who left Glass behind.[22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Thomas "Broken Hand" Fitzpatrick". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Sepehri, Sandy (2008-08-01). Native American Encyclopedia Confederacy To Fort Stanwix Treaty. Carson-Dellosa Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61741-898-3.

- ^ a b c d e Dungan, Myles (2011). How the Irish won the West. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-61608-100-3.

- ^ Trimble, Marshall (November 22, 2016). "Tom Fitzpatrick: Trapper, Scout and Indian Agent". True West Magazine. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- ^ a b c d e f Buckley, Jay H.; Rensink, Brenden W. (2015-05-05). Historical Dictionary of the American Frontier. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4422-4959-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n White, Lawrence William. "Fitzpatrick, Thomas ('Broken Hand')". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ Porter, Mae Reed; Davenport, Odessa (1963). Scotsman in Buckskin. New York: Hastings House. pp. 42, 51–52.

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia Staff (2020-06-09). "Teenokuhu (Friday)". coloradoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ a b Scott, High Lenox (1907). "The Early History and the Names of the Arapaho". American Anthropologist. 9 (3). American Anthropological Association: 554. doi:10.1525/aa.1907.9.3.02a00110 – via Anthrosource online library, Wiley.

- ^ "Chief Friday". Fort Collins History Connection. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ a b Dunn, Meg (17 November 2020). "Friday, the Arapaho - Northern Colorado History". Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ a b c Egan, Ferol (2012-08-01). Fremont: Explorer For A Restless Nation. University of Nevada Press. pp. PT1074. ISBN 978-0-87417-898-2.

- ^ Hyde, George E. (1967), Life of George Bent: Written from his Letters, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 84 ISBN 978-0-8061-1577-1

- ^ a b "Thomas Fitzpatrick death 1854". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1854-02-13. p. 2. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ a b c Hafen 1981, p. 274.

- ^ Thompson, Alice Anne (November 2019). "Margaret Poisal "Walking Woman" Fitzpatrick/Wilmott/McAdams". Wagon Tracks. 34 (1): 11–16 – via University of Mexico digital repository.

- ^ Coel, Margaret (2000). Chief Left Hand, Southern Arapaho. University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 47122540.

- ^ Howard R. Lamar, ed. (1998). The New Encyclopedia of the American West. Yale University Press.

- ^ Decisions of the United States Geographic Board, Decision List No. 7002, US Government Printing Office, p. 3.

- ^ "Hugh Glass Meets the Bear on Death Valley Days". IMDb. March 24, 1966. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ "John Alderson". Apple TV. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- ^ Thrapp, Dan L. (1991-08-01). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: G-O. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803294190.

Sources[edit]

- Hafen, LeRoy R. (1981). Broken Hand: The Life of Thomas Fitzpatrick, Mountain Man, Guide and Indian Agent. University of Nebraska Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-8032-7208-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Pedersen, Lyman C., "Warren Angus Ferris", in Trappers of the Far West, Leroy R. Hafen, editor. 1972, Arthur H. Clark Company, reprint University of Nebraska Press, October 1983. ISBN 0-8032-7218-9

- Utley, Robert M.; Dana, Peter M. (2004). After Lewis and Clark: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific. Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press.