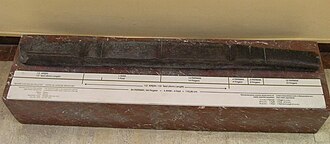

Timeline of historic inventions

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

The timeline of historic inventions is a chronological list of particularly important or significant technological inventions and their inventors, where known.[nb 1]

| History of technology |

|---|

Paleolithic[edit]

The dates listed in this section refer to the earliest evidence of an invention found and dated by archaeologists (or in a few cases, suggested by indirect evidence). Dates are often approximate and change as more research is done, reported and seen. Older examples of any given technology are often found. The locations listed are for the site where the earliest solid evidence has been found, but especially for the earlier inventions, there is little certainty how close that may be to where the invention took place.

Lower Paleolithic[edit]

The Lower Paleolithic period lasted over 3 million years, and corresponds to the human species prior to the emergence of Homo sapiens. The original divergence between humans and chimpanzees occurred 13 (Mya), however interbreeding continued until as recently as 4 Ma, with the first species clearly belonging to the human (and not chimpanzee) lineage being Australopithecus anamensis. This time period is characterized as an ice age with regular periodic warmer periods – interglacial episodes. Some species are controversial among paleoanthropologists, who disagree whether they are species on their own or not. Here Homo ergaster is included under Homo erectus, while Homo rhodesiensis is included under Homo heidelbergensis.

- 3.3 Mya - 2.6 Mya: Stone tools - found in modern day Kenya are older and only found on the archetype road. Ancient stone tools from Ethiopia (Oldowan) were hand-crafted by Australopithecus or related people.[1][2][further explanation needed]

- 2.3 Mya: Earliest likely control of fire and cooking, by Homo habilis[3][4][5]

- 1.76 Mya: Advanced (Acheulean) stone tools in Kenya by Homo erectus[6][7]

- 1.75 Mya - 150 kya: Varying estimates for the origin of language[8][9]

- 1.5 Mya: Bone tools in Africa by Homo erectus[10]

- 900 kya - 40 kya: Boats[11][12]

- 500 kya: Hafting in South Africa by Homo heidelbergensis[13]

- 450 kya - 500 kya: Woodworking construction in Zambia by Homo heidelbergensis[14]

- 400 kya: Pigments in Zambia by Homo heidelbergensis[15]

- 400 kya - 300 kya: Spears in Germany[16][17] likely by Homo heidelbergensis

Middle Paleolithic[edit]

The dawn of Homo sapiens around 300 kya coincides with the start of the Middle Paleolithic period. Towards the middle of this 250,000-year period, humans begin to migrate out of Africa, and the later part of the period shows the beginning of long-distance trade, religious rites and other behavior associated with Behavioral modernity.

- 320 kya: The trade and long-distance transportation of resources (e.g. obsidian), use of pigments, and possible making of projectile points in Kenya[18][19][20]

- 279 kya: Early stone-tipped projectile weapons in Ethiopia[21]

- 200 kya: Glue in Central Italy by Neanderthals.[22] More complicated compound adhesives developed by Homo sapiens have been found from c. 70 kya Sibudu, South Africa[23] and have been regarded as a sign of cognitive advancement.[24]

- 200 kya: Beds in South Africa.[25][26][27]

- 170 kya - 83 kya: Clothing (among anatomically modern humans in Africa).[28] Some other evidence suggests that humans may have begun wearing clothing as far back as 100,000 to 500,000 years ago.[29]

- 164 kya - 47 kya: Heat treating of stone blades in South Africa.[30]

- 135 kya - 100 kya: Beads in Israel and Algeria[31]

- 100 kya: Compound paints made in South Africa[32][33][34]

- 100 kya: Funerals (in the form of burial) in Israel[35]

- 90 kya: Harpoons in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[36]

- 70 kya - 60 kya: Oldest arrows (and evidence of bow-and-arrow technology), and oldest needle, at Sibudu, South Africa[37][38][39][40][41]

- 61 kya - 62 kya: Cave painting in Spain by Neanderthal[42]

Upper Paleolithic to Early Mesolithic[edit]

50 ka has been regarded by some as the beginning of behavioral modernity, defining the Upper Paleolithic period, which lasted nearly 40,000 years (though some research dates the beginning of behavioral modernity earlier to the Middle Paleolithic). This is characterized by the widespread observation of religious rites, artistic expression and the appearance of tools made for purely intellectual or artistic pursuits.

- 49 kya – 30 kya: Ground stone tools – fragments of an axe in Australia date to 49–45 ka, more appear in Japan closer to 30 ka, and elsewhere closer to the Neolithic.[43][44]

- 47 kya: The oldest-known mines in the world are from Eswatini, and extracted hematite for the production of the red pigment ochre.[45][46]

- 45 kya – 9 kya: Earliest evidence of shoes, suggested by changes in foot bone morphology in China by Tianyuan Man.[47] The earliest physical shoes found so far are bark sandals dated to 10 to 9 kya in Fort Rock Cave, United States.[48]

- 44 kya – 42 kya: Tally sticks (see Lebombo bone) in Eswatini[49]

- 42 kya: Flute in Germany[50][51]

- 37 kya: Mortar and pestle in Southwest Asia[52]

- 36 kya: Weaving – Indirect evidence from Moravia[53][54] and Georgia.[55] The earliest actual piece of woven cloth was found in Çatalhöyük, Turkey.[56][57]

- 33 kya - 10 kya: Star chart in France[58] and Spain[59]

- 28 kya: Rope[60]

- 26 kya: Ceramics in Europe[61]

- 23 kya: Domestication of the dog in Siberia.[62]

- 22 kya: Fishing hook in Okinawa Island modern day Japan.[63][64]

- 16 kya: Pottery in China[65]

- 14.5 kya: Bread in Jordan[66][67]

Agricultural and proto-agricultural eras[edit]

The end of the Last Glacial Period ("ice age") and the beginning of the Holocene around 11.7 ka coincide with the Agricultural Revolution, marking the beginning of the agricultural era, which persisted there until the industrial revolution.

Neolithic and Late Mesolithic[edit]

During the Neolithic period, lasting 8400 years, stone remained the predominant material for toolmaking, although copper and arsenic bronze were developed towards the end of this period.

- 10,000 BC - 9000 BC: Agriculture in the Fertile Crescent[68][69]

- 10,000 BC - 9000 BC: Domestication of sheep in Southwest Asia[70][71] (followed shortly by pigs, goats and cattle)

- 9000 BC - 6000 BC: Domestication of rice in China[72]

- 9000 BC: Oldest known surviving building – Göbekli Tepe, in Turkey[73]

- 9000 BC: Mudbricks, and clay mortar in Jericho.[74][75][76]

- 8400 BC: Oldest known water well in Cyprus.[77]

- 8000 BC – 7500 BC: Proto-city – large permanent settlements, such as Tell es-Sultan (Jericho) and Çatalhöyük, Turkey.[78]

- 7000 BC: Alcohol fermentation – specifically mead, in China[79]

- 7000 BC: Sled dog and Dog sled, in Siberia.[80]

- 7000 BC: Tanned leather in Mehrgarh, Pakistan.

- 6500 BC: Evidence of lead smelting in Çatalhöyük, Turkey[81]

- 6000 BC: Kiln in Mesopotamia (Iraq)[82]

- 6th millennium BC: Irrigation in Khuzistan, Iran[83][84]

- 6000 BC - 3200 BC: Proto-writing in present-day Egypt, Iraq, Romania, China, India and Pakistan.[85]

- 5500 BC: Sailing - pottery depictions of sail boats, in Mesopotamia,[86] and later ancient Egypt[87][88]

- 5000 BC: Copper smelting in Serbia[89]

- 5000 BC: Seawall in Tel Hreiz.[90]

- 5th millennium BC: Lacquer in China[91][92]

- 5000 BC: Cotton thread, in Mehrgarh, Pakistan, connecting the copper beads of a bracelet.[93][94][95]

- 5000 BC – 4500 BC: Rowing oars in China[96][97]

- 4650 BC: Copper-tin bronze found at the Pločnik (Serbia) site, and belonging to the Vinča culture, believed to be produced from smelting a natural tin baring copper ore, Stannite.[98]

- 4500 BC – 3500 BC: Lost-wax casting in Israel[99] or the Indus Valley[100]

- 4400 BC: Fired bricks in China.[101]

- 4000 BC: Probable time period of the first diamond-mines in the world, in Southern India.[102]

- 4000 BC: Paved roads, in and around the Mesopotamian city of Ur, Iraq.[103]

- 4000 BC: Plumbing. The earliest pipes were made of clay, and are found at the Temple of Bel at Nippur in Babylonia.[104][nb 2]

- 4000 BC – 3500 BC: Wheel: potter's wheels in Mesopotamia and wheeled vehicles in Mesopotamia (Sumerian civilization), the Northern Caucasus (Maykop culture) and Central Europe (Cucuteni–Trypillia culture).[107][108][109]

- 3630 BC: Silk garments (sericulture) in China[110]

- 3500 BC: Probable first domestication of the horse in the Eurasian Steppes.[111][112][113]

- 3500 BC: Wine as general anesthesia in Sumer.[114]

- 3500 BC: Seal (emblem) invented around in the Near East, at the contemporary sites of Uruk in southern Mesopotamia and slightly later at Susa in south-western Iran during the Proto-Elamite period, and they follow the development of stamp seals in the Halaf culture or slightly earlier.[115]

- 3500 BC: Ploughing, on a site in Bubeneč, Czech Republic.[116] Evidence, c. 2800 BC, has also been found at Kalibangan, Indus Valley (modern-day India).[117]

- 3400 BC - 3100 BC: Tattoos in southern Europe[118][119]

Bronze Age[edit]

The beginning of bronze-smelting coincides with the emergence of the first cities and of writing in the Ancient Near East and the Indus Valley. The Bronze Age starting in Eurasia in the 4th millennia BC and ended, in Eurasia, c.1300 BC.

- Late 4th millennium BC: Writing – in Sumer and Egypt.[120][121][122][123]

- 3300 BC: The first documented swords. They have been found in Arslantepe, Turkey, are made from arsenical bronze, and are about 60 cm (24 in) long.[124][125] Some of them are inlaid with silver.[125]

- 3300 BC: City in Uruk, Sumer, Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq).[126]

- 3250 BC: One of the earliest known confirmed hats was worn by a man (nicknamed Ötzi) whose body (including his hat) was found frozen in a mountain between Austria and Italy. He was found wearing a bearskin cap with a chin strap, made of several hides stitched together, essentially resembling a Russian fur hat without the flaps.[127][128][129]

- 3200 BC: Dry Latrines in the city of Uruk, Iraq, with later dry squat Toilets, that added raised fired brick foot platforms, and pedestal toilets, all over clay pipe constructed drains.[130][131][132]

- 3000 BC: Devices functionally equivalent to dice, in the form of flat two-sided throwsticks, are seen in the Egyptian game of Senet.[133] Perhaps the oldest known dice, resembling modern ones, were excavated as part of a backgammon-like game set at the Burnt City, an archeological site in south-eastern Iran, estimated to be from between 2800 and 2500 BC.[134][135] Later, terracotta dice were used at the Indus Valley site of Mohenjo-daro (modern-day Pakistan).[136]

- 3000 BC: Tin extraction in Central Asia[137]

- 3000 BC - 2560 BC: Papyrus in Egypt[138][139][140][141]

- 3000 BC: Reservoir in Girnar, Indus Valley (modern-day India).[142]

- 3000 BC: Receipt in Ancient Mesopotamia (Iraq)[143]

- 3000 BC - 2800 BC: Prosthesis first documented in the Ancient Near East, in ancient Egypt and Iran, specifically for an eye prosthetics, the eye found in Iran was likely made of bitumen paste that was covered with a thin layer of gold.[144]

- 3000 BC - 2500 BC: Rhinoplasty in Egypt.[145][146]

- 2650 BC: The Ruler, or Measuring rod, in the subdivided Nippur, copper rod, of the Sumerian Civilisation (modern-day Iraq). [nb 3]

- 2600 BC: Planned city in Indus Valley (modern-day: India, Pakistan).[148][149]

- 2600 BC: Public sewage and sanitation systems in Indus Valley sites such as Mohenjo-daro and Rakhigarhi (modern-day: India, Pakistan).[150]

- 2600 BC: Public bath in Mohenjo-daro, Indus Valley (modern-day Pakistan).[151]

- 2600 BC: Levee in Indus Valley.[152]

- 2600 BC: Balance weights and scales, from the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt; examples of Deben (unit) balance weights, from reign of Sneferu (c. 2600 BC) have been attributed.[153]

- 2556 BC: Docks structure in Wadi al-Jarf, Egypt, which was developed by the reign of the Pharaoh Khufu.[154][141] [nb 4]

- 2500 BC: Puppetry in the Indus Valley.[161][162]

- 2400 BC: Fork in Bronze Age Qijia culture in China[163]

- 2400 BC: Copper pipes, the Pyramid of Sahure, an adjoining temple complex at Abusir, was discovered to have a network of copper drainage pipes.[106]

- 2400 BC: Touchstone in the Indus Valley site of Banawali (modern-day India).[164]

- 2300 BC: Dictionary in Mesopotamia.[165]

- 2200 BC: Protractor, Phase IV, Lothal, Indus Valley (modern-day India), a Xancus shell cylinder with sawn grooves, at right angles, in its top and bottom surfaces, has been proposed as an angle marking tool.[166][167]

- 2000 BC: Water clock by at least the old Babylonian period (c. 2000 – c. 1600 BC),[168] but possibly earlier from Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley.[169]

- 2000 BC: Chariot in Russia and Kazakhstan[170]

- 2000 BC: Fountain in Lagash, Sumer

- 2000 BC: Scissors, in Mesopotamia.[171]

- 1850 BC: Proto-alphabet (Proto-Sinaitic script) in Egypt.[172]

- 1600 BC: Surgical treatise appeared in Egypt.[173]

- 1500 BC: Sundial in Ancient Egypt[174] or Babylonia (modern-day Iraq).

- 1500 BC: Glass manufacture in either Mesopotamia or Ancient Egypt[175]

- 1500 BC: Seed drill in Babylonia[176]

- 1400 BC: Rubber, Mesoamerican ballgame.[177][178]

- 1400 BC - 1200 BC: Concrete in Tiryns (Mycenaean Greece).[179][180] Waterproof concrete was later developed by the Assyrians in 688 BC,[181] and the Romans developed concretes that could set underwater.[182] The Romans later used concrete extensively for construction from 300 BC to 476 AD.[183]

- 1300 BC: Lathe in Ancient Egypt[184]

Iron Age[edit]

The Late Bronze Age collapse occurs around 1300-1175 BC , extinguishing most Bronze-Age Near Eastern cultures, and significantly weakening the rest. This is coincident with the complete collapse of the Indus Valley civilisation. This event is followed by the beginning of the Iron Age. We define the Iron Age as ending in 510 BC for the purposes of this article, even though the typical definition is region-dependent (e.g. 510 BC in Greece, 322 BC in India, 200 BC in China), thus being an 800-year period.[nb 5]

- 1300 BC: Iron smelting in the Hittite Empire of the Middle East.[185][186]

- 1200 BC: Distillation is described on Akkadian tablets documenting perfumery operations.[187]

- 700 BC: Saddle (fringed cloths or pads used by Assyrian cavalry)[188]

- 7th century BC: The royal Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh had 30,000 clay tablets, in several languages, organized according to shape and separated by content. The first recorded example of a library catalog.[189]

- 650 BC: Crossbow in China.[190]

- 650 BC: Windmills in Persia

- 600 BC: Coins in Phoenicia (Modern Lebanon) or Lydia[191]

- Late 7th or early 6th century BC: Wagonway called Diolkos across the Isthmus of Corinth in Ancient Greece

- 6th century BC - 10th century AD: High Carbon Steel, produced by the Closed Crucible method, later known as Wootz steel, of South India.[193][194][nb 6]

- 6th century BC: University in Taxila, of the Indus Valley, then part of the kingdom of Gandhara, of the Achaemenid Empire (modern-day Pakistan).

- 6th century - 2nd century BC: Systematization of medicine and surgery in the Sushruta Samhita in Vedic Northern India.[196][197][198] Documented procedures to:

- Perform cataract surgery (couching). Babylonian and Egyptian texts, a millennium before, depict and mention oculists, but not the procedure itself.[199]

- Perform Caesarean section.[200]

- Construct Prosthetic limbs.[200]

- Perform Plastic surgery, though reconstructive nasal surgery is described in millennia older Egyptian papyri.[200][201]

- Late 6th century BC: Crank motion (rotary quern) in Carthage[202] or 5th century BC Celtiberian Spain[203][204] Later during the Roman empire, a mechanism appeared that incorporated a connecting rod.

- Before 5th century BC: Loan deeds in Upanishadic India.[205]

- 500 BC: Lighthouse in Greece[206]

Classical antiquity and medieval era[edit]

5th century BC[edit]

- 500 - 200 BC: Toe stirrup, depicted in 2nd century Buddhist art, of the Sanchi and Bhaja Caves, of the Deccan Satavahana empire (modern-day India)[207][208] although may have originated as early as 500 BC.[209]

- 485 BC: Catapult by Ajatashatru in Magadha, India.[210][211]

- 485 BC: Scythed chariot by Ajatashatru in Magadha, India.[210][211]

- 5th century BC: Cast iron in Ancient China: Confirmed by archaeological evidence, the earliest cast iron is developed in China by the early 5th century BC during the Zhou Dynasty (1122–256 BC), the oldest specimens found in a tomb of Luhe County in Jiangsu province.[212][213][214]

- 480 BC: Spiral stairs (Temple A) in Selinunte, Sicily (see also List of ancient spiral stairs)[215][216]

- By 407 BC: Early descriptions of what may be a Wheelbarrow in Greece.[217] First actual depiction of one (tomb mural) shows up in China in 118 AD.[218]

- By 400 BC: Camera obscura described by Mo-tzu (or Mozi) in China.[219]

4th century BC[edit]

- 4th century BC: Traction trebuchet in Ancient China.[221]

- 4th century BC: Gears in Ancient China

- 4th century BC: Reed pens, utilising a split nib, were used to write with ink on Papyrus in Egypt.[221]

- 4th century BC: Nailed Horseshoe, with 4 bronze shoes found in an Etruscan tomb.[222]

- 375 BC – 350 BC: Animal-driven rotary mill in Carthage.[223][224]

- By the late 4th century BC: Corporations in either the Maurya Empire of India[225] or in Ancient Rome (Collegium).

- Late 4th century BC: Cheque in the Maurya Empire of India.[226]

- Late 4th century BC: Potassium nitrate manufacturing and military use in the Seleucid Empire.[227]

- Late 4th century BC: Formal systems by Pāṇini in India, possibly during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya.[228]

- 4th to 3rd century BC: Zinc production in North-Western India during the Maurya Empire.[229] The earliest known zinc mines and smelting sites are from Zawar, near Udaipur, in Rajasthan.[230][231]

3rd century BC[edit]

- 3rd century BC: Analog computers in the Hellenistic world (see e.g. the Antikythera mechanism), possibly in Rhodes.[232]

- By at least the 3rd century BC: Archimedes' screw, one of the earliest hydraulic machines, was first used in the Nile river for irrigation purposes in Ancient Egypt[233]

- Early 3rd century BC: Canal lock in Canal of the Pharaohs under Ptolemy II (283–246 BC) in Hellenistic Egypt[234][235][236]

- 3rd century BC: Cam during the Hellenistic period, used in water-driven automata.[237]

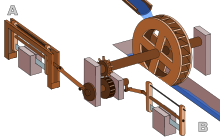

- By the 3rd century BC: Water wheel. The origin is unclear: Indian Pali texts dating to the 4th century BCE refer to the cakkavattaka, which later commentaries describe as arahatta-ghati-yanta (machine with wheel-pots attached). Helaine Selin suggests that the device existed in Persia before 350 BC.[238] The clearest description of the water wheel and Liquid-driven escapement is provided by Philo of Byzantium (c. 280 – 220 BC) in the Hellenistic kingdoms.[239]

- 3rd century BC: Gimbal described by Philo of Byzantium[240]

- Late 3rd century BC: Dry dock under Ptolemy IV (221–205 BC) in Hellenistic Egypt[241]

- 3rd century BC – 2nd century BC: Blast furnace in Ancient China: The earliest discovered blast furnaces in China date to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, although most sites are from the later Han dynasty.[212][242]

2nd century BC[edit]

- 2nd century BC: Paper in Han dynasty China[nb 7]

- 206 BC: Compass in Han dynasty China[245]

- Early 2nd century BC: Astrolabe invented by Apollonius of Perga.

1st century BC[edit]

- 1st century BC: Segmental arch bridge (e.g. Pont-Saint-Martin or Ponte San Lorenzo) in Italy, Roman Republic[246][247]

- 1st century BC: News bulletin during the reign of Julius Caesar.[248] A paper form, i.e. the earliest newspaper, later appeared during the late Han dynasty in the form of the Dibao.[249][250][251]

- 1st century BC: Arch dam (Glanum Dam) in Gallia Narbonensis, Roman Republic (see also List of Roman dams)[252][253][254][255][256]

- Before 40 BC: Trip hammer in China[257]

- 38 BC: An empty shell Glyph for zero, is found on a Maya numerals Stela, from Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas. Independently invented by Claudius Ptolemy, in the second century CE Egypt, and appearing in the calculations of the Almagest.

- 37 BC - 14 BC: Glass blowing developed in Jerusalem.[258][259][260]

- Before 25 BC: Reverse overshot water wheel by Roman engineers in Rio Tinto, Spain[261]

- 25 BC: Noodle in Lajia in China[262]

1st century AD[edit]

- 1st century AD: The aeolipile, a simple steam turbine is recorded by Hero of Alexandria.[263]

- 1st century AD: The first use of respiratory protective equipment is documented by Pliny the Elder (c. 23 AD–79) using animal bladder skins to protect workers in Roman mines from red lead oxide dust.[264]

- 1st century AD: Vending machines invented by Hero of Alexandria.

- By the 1st century AD: The double-entry bookkeeping system in the Roman Empire.[265]

2nd century[edit]

- 132: Seismometer and pendulum in Han dynasty China, built by Zhang Heng. It is a large metal urn-shaped instrument which employed either a suspended pendulum or inverted pendulum acting on inertia, like the ground tremors from earthquakes, to dislodge a metal ball by a lever trip device.[266][267]

- 2nd century: Carding in India.[268]

3rd century[edit]

- By at least the 3rd century: Crystallized sugar in India.[272]

- Early 3rd century: Woodblock printing is invented in Han dynasty China at sometime before 220 AD. This made China become the world's first print culture.[273]

- Late 3rd century – Early 4th century: Water turbine in the Roman Empire in modern-day Tunisia.[274][275][276]

4th century[edit]

- 280 - 550: Chaturanga, a precursor of Chess was invented in India during the Gupta Empire.[277][278][279]

- 4th century: Roman Dichroic glass, which displays one of two different colors depending on lighting conditions.

- 4th century: Mariner's compass in Tamil Southern India: the first mention of the use of a compass for navigational purposes is found in Tamil nautical texts as the macchayantra.[280][281] However, the theoretical notion of magnets pointing North predates the device by several centuries.

- 4th century: Simple suspension bridge, independently invented in Pre-Columbian South America, and the Hindu Kush range, of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. With Han dynasty travelers noting bridges being constructed from 3 or more vines or 3 ropes.[282] Later bridges constructed utilizing cables of iron chains appeared in Tibet.[283][284]

- 4th century: Fishing reel in Ancient China: In literary records, the earliest evidence of the fishing reel comes from a 4th-century AD[285] work entitled Lives of Famous Immortals.[286]

- 347: Oil Wells and Borehole drilling in China. Such wells could reach depths of up to 240 m (790 ft).[287]

- 4th century – 5th century: Paddle wheel boat (in De rebus bellicis) in Roman Empire[288]

5th century[edit]

- 400: The construction of the Iron pillar of Delhi in Mathura by the Gupta Empire shows the development of rust-resistant ferrous metallurgy in Ancient India,[289][290] although original texts do not survive to detail the specific processes invented in this period.

- 5th century: The horse collar as a fully developed collar harness is developed in Southern and Northern Dynasties China during the 5th century AD.[291] The earliest depiction of it is a Dunhuang cave mural from the Chinese Northern Wei Dynasty, the painting dated to 477–499.[292]

- 5th century - 6th century: Pointed arch bridge (Karamagara Bridge) in Cappadocia, Eastern Roman Empire[293][294]

6th century[edit]

- By the 6th century: Incense clock in China.[295][296]

- After 500: Charkha (spinning wheel/cotton gin) invented in India (probably during the Vakataka dynasty of Maharashtra, India), between 500 and 1000 A.D.[297]

- 563: Pendentive dome (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, Eastern Roman Empire[298]

- 577: Sulfur matches exist in China.

- 589: Toilet paper in Sui dynasty China, first mentioned by the official Yan Zhitui (531–591), with full evidence of continual use in subsequent dynasties.[299][300]

7th century[edit]

- 619: Toothbrush in China during the Tang Dynasty[301]

- 672: Greek fire in Constantinople, Byzantine Empire: Greek fire, an incendiary weapon likely based on petroleum or naphtha, is invented by Kallinikos, a Lebanese Greek refugee from Baalbek, as described by Theophanes.[302] However, the historicity and exact chronology of this account is dubious,[303] and it could be that Kallinikos merely introduced an improved version of an established weapon.[304]

- 7th century: Banknote in Tang dynasty China: The banknote is first developed in China during the Tang and Song dynasties, starting in the 7th century. Its roots are in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desire to avoid the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions.[305][306][307]

- 7th century: Porcelain in Tang dynasty China: True porcelain is manufactured in northern China from roughly the beginning of the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century, while true porcelain was not manufactured in southern China until about 300 years later, during the early 10th century.[308]

8th century[edit]

9th century[edit]

- 9th century: Gunpowder in Tang dynasty China: Gunpowder is, according to prevailing academic consensus, discovered in the 9th century by Chinese alchemists searching for an elixir of immortality.[309] Evidence of gunpowder's first use in China comes from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (618–907).[310] The earliest known recorded recipes for gunpowder are written by Zeng Gongliang, Ding Du, and Yang Weide in the Wujing Zongyao, a military manuscript compiled in 1044 during the Song Dynasty (960–1279).[311][312][313]

- 9th century: Playing card in Tang Dynasty China[314][315][316][317][318]

- 857 - 859: Degree-granting university in Morocco[319]

10th century[edit]

- 10th century: Fire lance in Song dynasty China, developed in the 10th century with a tube of first bamboo and later on metal that shot a weak gunpowder blast of flame and shrapnel, its earliest depiction is a painting found at Dunhuang.[320] Fire lance is the earliest firearm in the world and one of the earliest gunpowder weapons.[321][322]

- 10th century: Fireworks in Song dynasty China: Fireworks first appear in China during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), in the early age of gunpowder. Fireworks could be purchased from market vendors; these were made of sticks of bamboo packed with gunpowder.[323]

- 974: Fountain pen: invented at the request of al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah in Arab Egypt.[324]

11th century[edit]

- 11th century: Early versions of the Bessemer process are developed in China.

- 11th century: Endless power-transmitting chain drive by Su Song for the development an astronomical clock (the Cosmic Engine)[325]

- 1088: Movable type in Song dynasty China: The first record of a movable type system is in the Dream Pool Essays, which attributes the invention of the movable type to Bi Sheng.[326][327][328][329]

12th century[edit]

13th century[edit]

- 13th century: Rocket for military and recreational uses date back to at least 13th-century China.[330]

- 13th century: The earliest form of mechanical escapement, the verge escapement in Europe.[331]

- 13th century: Buttons (combined with buttonholes) as a functional fastening for closing clothes appear first in Germany.[332]

- 13th century: Explosive bomb in Jin dynasty Manchuria: Explosive bombs are used in 1221 by the Jin dynasty against a Song Dynasty city.[333] The first accounts of bombs made of cast iron shells packed with explosive gunpowder are documented in the 13th century in China and are called "thunder-crash bombs",[334] coined during a Jin dynasty naval battle in 1231.[335]

- 13th century: Hand cannon in Yuan dynasty China: The earliest hand cannon dates to the 13th century based on archaeological evidence from a Heilongjiang excavation. There is also written evidence in the Yuanshi (1370) on Li Tang, an ethnic Jurchen commander under the Yuan Dynasty who in 1288 suppresses the rebellion of the Christian prince Nayan with his "gun-soldiers" or chongzu, this being the earliest known event where this phrase is used.[336]

- 13th century: Earliest documented snow goggles, a type of sunglasses, made of flattened walrus or caribou ivory are used by the Inuit peoples in the arctic regions of North America.[337][338] In China, the first sunglasses consisting of flat panes of smoky quartz are documented.[339][340]

- 13th century - 14th century: Worm gear cotton gin in India.[341]

- 1277: Land mine in Song dynasty China: Textual evidence suggests that the first use of a land mine in history is by a Song Dynasty brigadier general known as Lou Qianxia, who uses an 'enormous bomb' (huo pao) to kill Mongol soldiers invading Guangxi in 1277.[342]

- 1286: Eyeglasses in Italy[343]

14th century[edit]

- Early 14th century - Mid 14th century: Multistage rocket in Ming dynasty China described in Huolongjing by Jiao Yu.

- By at least 1326: Cannon in Ming dynasty China[344]

- 14th century: Jacob's staff described by Levi ben Gerson

- 14th century: Naval mine in Ming dynasty China: Mentioned in the Huolongjing military manuscript written by Jiao Yu (fl. 14th to early 15th century) and Liu Bowen (1311–1375), describing naval mines used at sea or on rivers and lakes, made of wrought iron and enclosed in an ox bladder. A later model is documented in Song Yingxing's encyclopedia written in 1637.[345]

- 14th century: Bidriware in the Bahmani Sultanate in India.[346]

15th century[edit]

- Early 15th century: Coil spring in Europe[348]

- 15th century: Mainspring in Europe[348]

- 15th century: Rifle in Europe

- 1420s: Brace in Flandres, Holy Roman Empire[349]

- 1439: Printing press in Mainz, Germany: The printing press is invented in the Holy Roman Empire by Johannes Gutenberg before 1440, based on existing screw presses. The first confirmed record of a press appeared in a 1439 lawsuit against Gutenberg.[350]

- Mid 15th century: The Arquebus (also spelled Harquebus) is invented, possibly in Spain.[351][352]

- 1480s: Mariner's astrolabe in Portuguese circumnavigation of Africa[353]

Early modern era[edit]

16th century[edit]

- 16th century: Chintz or printed clothing in Golconda, India[354]

- 16th century: Hookah by Irfan Shaikh, at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar I (1542–1605).

- 1560: Floating Dry Dock in Venice, Venetian Republic[357]

- 1569: Mercator Projection map created by Gerardus Mercator

- 1589: Stocking frame: Invented by William Lee.[358]

- 1589-1590: Seamless globe was invented in Kashmir (then Mughal India) by Ali Kashmiri ibn Luqman.[359][360]

- 1594: Backstaff: Invented by Captain John Davis.

- By at least 1597: Revolver: Invented by Hans Stopler.

17th century[edit]

- 1605: Newspaper (Relation): Johann Carolus in Strassburg (see also List of the oldest newspapers)[361][362]

- 1608: Telescope: Patent applied for by Hans Lippershey. Actual inventor unknown since it seemed to already be a common item being offered by the spectacle makers in the Netherlands with Jacob Metius also applying for patent and the son of Zacharias Janssen making a claim 47 years later that his father invented it.

- 1620: Compound microscopes, which combine an objective lens with an eyepiece to view a real image, first appear in Europe. Apparently derived from the telescope, actual inventor unknown, variously attributed to Zacharias Janssen (his son claiming it was invented in 1590), Cornelis Drebbel, and Galileo Galilei.[363]

- 1630: Slide rule: invented by William Oughtred[364][365]

- 1642: Mechanical calculator. The Pascaline is built by Blaise Pascal.[366]

- 1643: Barometer: invented by Evangelista Torricelli, or possibly up to three years earlier by Gasparo Berti.[367]

- 1650: Vacuum pump: Invented by Otto von Guericke.[368]

- 1656: Pendulum clock: Invented by Christiaan Huygens. It was first conceptualized in 1637 by Galileo Galilei but he was unable to create a working model.[369]

- 1663: Friction machine: Invented by Otto von Guericke.

- 1668: First functional reflecting telescope constructed by Isaac Newton.[370]

- 1679: Pressure-cooker: Invented by Denis Papin.[371]

- 1680: Christiaan Huygens provides the first known description of a piston engine.[372]

- 1698: Thomas Savery developes a steam-powered water pump: for draining mines[373]

18th century[edit]

1700s[edit]

- 1709: Bartolomeo Cristofori crafts the first piano.

- 1709: Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit invents the alcohol thermometer.

1710s[edit]

- 1712: Thomas Newcomen builds the first commercial steam engine to pump water out of mines.[374] Newcomen's engine, unlike Thomas Savery's, uses a piston.

1730s[edit]

- 1730: Thomas Godfrey and John Hadley independently develop the octant

- 1733: John Kay enables one person to operate a loom with the flying shuttle[375]

- 1738: Lewis Paul and John Wyatt invent the first mechanized cotton spinning machine.

1740s[edit]

- 1742: Benjamin Franklin invents the Franklin stove.

- 1745: Musschenbroek and Kleist independently develop the Leyden jar, an early form of capacitor.

- 1746: John Roebuck invents the lead chamber process.

1750s[edit]

- 1752: Benjamin Franklin invents the lightning rod.

- 1755: William Cullen invents the first artificial refrigeration machine.

1760s[edit]

- 1760: John Joseph Merlin invents the first Roller skates.[376]

- 1764: James Hargreaves invents the spinning jenny.

- 1765: James Watt invents the improved steam engine utilizing a separate condenser.

- 1767: Joseph Priestley invents a method for the production of carbonated water.

- 1769: Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot invents the first steam-powered vehicle capable of carrying passengers, an early car.

1770s[edit]

- 1770: Richard Salter invents the earliest known design for a weighing scale.

- 1774: John Wilkinson invents his boring machine, considered by some to be the first machine tool.

- 1775: Jesse Ramsden invents the modern screw-cutting lathe.

- 1776: John Wilkinson invents a mechanical air compressor that would become the prototype for all later mechanical compressors.

- 1778: Robert Barron invents the first lever tumbler lock.

1780s[edit]

- 1780: Hyder Ali of Mysore develops the first metal-cylinder rockets.[377]

- 1783: Claude de Jouffroy builds the first steamboat.

- 1783: Joseph-Ralf and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier build the first manned hot air balloon.

- 1783: Louis-Sébastien Lenormand invents and uses the first modern parachute.

- 1785: Martinus van Marum is the first to use the electrolysis technique.

- 1786: Andrew Meikle invents the threshing machine.

- 1789: Edmund Cartwright invents the power loom.

1790s[edit]

- 1790: Thomas Saint invents the sewing machine.

- 1792: Claude Chappe invents the modern semaphore telegraph.

- 1793: Eli Whitney invents the modern cotton gin.

- 1795: Joseph Bramah invents the hydraulic press.

- 1796: Alois Senefelder invents the lithography printing technique.[378]

- 1797: Samuel Bentham invents plywood.

- 1799: George Medhurst invents the first motorized air compressor.

- 1799: The first paper machine is invented by Louis-Nicolas Robert.

Late modern period[edit]

19th century[edit]

1800s[edit]

- 1800: Alessandro Volta invents the voltaic pile, an early form of battery in Italy, based on previous works by Luigi Galvani.

- 1802: Humphry Davy invents the arc lamp (exact date unclear; not practical as a light source until the invention of efficient electric generators).[379]

- 1804: Friedrich Sertürner discovers morphine as the first active alkaloid extracted from the opium poppy plant.[380]

- 1804: Joseph Marie Jacquard develops his automated Jacquard loom.[381]

- 1804: Richard Trevithick invents the steam locomotive.[382]

- 1804: Hanaoka Seishū creates tsūsensan, the first modern general anesthetic.[383]

- 1807: Nicéphore Niépce invents an early internal combustion engine capable of doing useful work.

- 1807: François Isaac de Rivaz designs the first automobile powered by an internal combustion engine fuelled by hydrogen.

- 1807: Robert Fulton expands water transportation and trade with the workable steamboat.

1810s[edit]

- 1810: Nicolas Appert invents the canning process for food.

- 1810: Abraham-Louis Breguet creates the first wristwatch.[384]

- 1811: Friedrich Koenig invents the first powered printing press, which was also the first to use a cylinder.

- 1812: William Reid Clanny pioneered the invention of the safety lamp which he improved in later years. Safety lamps based on Clanny's improved design were used until the adoption of electric lamps.

- 1814: James Fox invents the modern planing machine, though Matthew Murray of Leeds and Richard Roberts of Manchester have also been credited at times with its invention.

- 1816: René Laennec invents the first Stethoscope.[385]

- 1816: Francis Ronalds builds the first working electric telegraph using electrostatic means.

- 1816: Robert Stirling invents the Stirling engine.[386]

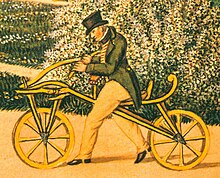

- 1817: Baron Karl von Drais invents the dandy horse, an early velocipede and precursor to the modern bicycle.

- 1818: Marc Isambard Brunel invents the tunnelling shield.

1820s[edit]

- 1822: Thomas Blanchard invents the pattern-tracing lathe (actually more like a shaper). The lathe can copy symmetrical shapes and is used for making gun stocks, and later, ax handles.[387][388]

- 1822: Nicéphore Niépce invents Heliography, the first photographic process.

- 1822: Charles Babbage, considered the "father of the computer",[389] begins building the first programmable mechanical computer.

- 1823: Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner invents the first lighter.

- 1824: Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse invents the bolt-action rifle.[390]

- 1825: William Sturgeon invents the electromagnet.

- 1826: John Walker invents the friction match.[391]

- 1826: James Sharp invents and goes on to manufacture the first practical gas stove.

- 1828: James Beaumont Neilson develops the hot blast process.

- 1828: Patrick Bell invents the reaping machine.

- 1828: Hungarian physicist Ányos Jedlik invents the first commutated rotary electromechanical machine with electromagnets.

- 1829: Louis Braille invents the Braille reading system for the blind.[392]

- 1829: William Mann invents the compound air compressor.

- 1829: Henry Robinson Palmer is awarded a patent for corrugated galvanised iron.

1830s[edit]

- 1830: Edwin Budding invents the lawn mower.

- 1831: Michael Faraday invents a method of electromagnetic induction. It would be independently invented by Joseph Henry the following year.

- 1834: Moritz von Jacobi invents the first practical electric motor.

- 1835: Joseph Henry invents the electromechanical relay.

- 1837: Samuel Morse invents Morse code.

- 1838: Moritz von Jacobi invents electrotyping.

- 1839: William Otis invents the steam shovel.

- 1839: James Nasmyth invents the steam hammer.

- 1839: Edmond Becquerel invents a method for the photovoltaic effect, effectively producing the first solar cell.

- 1839: Charles Goodyear invents vulcanized rubber.[393]

- 1839: Louis Daguerre invents daguerreotype photography.[394]

1840s[edit]

- 1840: John Herschel invents the blueprint.[395]

- 1841: Alexander Bain devises a printing telegraph.[396]

- 1842: William Robert Grove invents the first fuel cell.

- 1842: John Bennet Lawes invents superphosphate, the first man-made fertilizer.

- 1844: Friedrich Gottlob Keller and, independently, Charles Fenerty come up with the wood pulp method of paper production.

- 1845: Isaac Charles Johnson invents modern Portland cement.

- 1846: Henri-Joseph Maus invents the tunnel boring machine.

- 1847: Ascanio Sobrero invents Nitroglycerin, the first explosive made that was stronger than black powder.

- 1848: Jonathan J. Couch invents the pneumatic drill.

- 1848: Linus Yale Sr. invents the first modern pin tumbler lock.

- 1849: Walter Hunt invents the first repeating rifle to use metallic cartridges (of his own design) and a spring-fed magazine.

- 1849: James B. Francis invents the Francis turbine.

- 1849: Walter Hunt invents the Safety pin.[397]

1850s[edit]

- 1850: William Armstrong invents the hydraulic accumulator.

- 1851: George Jennings offers the first public flush toilets, accessible for a penny per visit, and in 1852 receives a UK patent for the single piece, free standing, earthenware, trap plumed, flushing, water-closet.[398]

- 1852: Robert Bunsen is the first to use a chemical vapor deposition technique.

- 1852: Elisha Otis invents the safety brake elevator.[399]

- 1852: Henri Giffard becomes the first person to make a manned, controlled and powered flight using a dirigible.

- 1853: François Coignet invents reinforced concrete.

- 1855: James Clerk Maxwell invents the first practical method for color photography, whether chemical or electronic.

- 1855: Henry Bessemer patents the Bessemer process for making steel, with improvements made by others over the following years.

- 1856: Alexander Parkes invents parkesine, also known as celluloid, the first man-made plastic.

- 1856: James Harrison produces the world's first practical ice making machine and refrigerator using the principle of vapour compression in Geelong, Australia.[400]

- 1856: William Henry Perkin invents mauveine, the first synthetic dye.

- 1857: Heinrich Geissler invents the Geissler tube.

- 1857: The phonautograph, the earliest known device for recording sound is patented and invented by Frenchman Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville.

- 1859: Gaston Planté invents the lead acid battery, the first rechargeable battery.

1860s[edit]

- 1860: Joseph Swan produces carbon fibers.[401]

- 1864: Louis Pasteur invents the pasteurization process.

- 1865: Carl Wilhelm Siemens and Pierre-Émile Martin invented the Siemens-Martin process for making steel.

- 1867: Alfred Nobel invents dynamite, the first safely manageable explosive stronger than black powder.

- 1867: Lucien B. Smith invents barbed wire, which Joseph F. Glidden will modify in 1874, leading to the taming of the West and the end of the cowboys.

1870s[edit]

- 1872: Polyvinyl chloride, more commonly known as vinyl, is synthesized by German chemist Eugen Baumann

- 1872: J.E.T. Woods and J. Clark invented stainless steel. Harry Brearley was the first to commercialize it.[402]

- 1873: Frederick Ransome invents the rotary kiln.

- 1873: William Crookes, a chemist, invents the Crookes radiometer as the by-product of some chemical research.

- 1873: Zénobe Gramme invents the first commercial electrical generator, the Gramme machine.

- 1874: Gustave Trouvé invents the first metal detector.

- 1875: Fyodor Pirotsky invents the first electric tram near Saint Petersburg, Russia.

- 1876: Nicolaus August Otto invents the four-stroke cycle.

- 1876: Alexander Graham Bell has a patent granted for the telephone. However, other inventors before Bell had worked on the development of the telephone and the invention had several pioneers.[403]

- 1877: Thomas Edison invents the first working phonograph.[404]

- 1878: Henry Fleuss is granted a patent for the first practical rebreather.[405]

- 1878: Lester Allan Pelton invents the Pelton wheel.

- 1879: Joseph Swan and Thomas Edison both patent a functional incandescent light bulb. Some two dozen inventors had experimented with electric incandescent lighting over the first three-quarters of the 19th century but never came up with a practical design.[406] Swan's, which he had been working on since the 1860s, had a low resistance so was only suited for small installations. Edison designed a high-resistance bulb as part of a large-scale commercial electric lighting utility.[407][408][409]

1880s[edit]

- 1881: Nikolay Benardos presents carbon arc welding, the first practical arc welding method.[410]

- 1884: Hiram Maxim invents the recoil-operated Maxim gun, ushering in the age of semi- and fully automatic firearms.

- 1884: Paul Vieille invents Poudre B, the first smokeless powder for firearms.

- 1884: Sir Charles Parsons invents the modern steam turbine.

- 1884: Hungarian engineers Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy and Miksa Déri invent the closed core high efficiency transformer and the AC parallel power distribution.

- 1885: John Kemp Starley invents the modern safety bicycle.[411][412]

- 1886: Carl Gassner invents the zinc–carbon battery, the first dry cell battery, making portable electronics practical.

- 1886: Charles Martin Hall and independently Paul Héroult invent the Hall–Héroult process for economically producing aluminum in 1886.

- 1886: Karl Benz invents the first petrol or gasoline powered auto-mobile (car).[413]

- 1887: Carl Josef Bayer invents the Bayer process for the production of alumina.

- 1887: James Blyth invents the first wind turbine used for generating electricity.

- 1887: John Stewart MacArthur, working in collaboration with brothers Dr. Robert and Dr. William Forrest develops the process of gold cyanidation.

- 1888: John J. Loud invents the ballpoint pen.[414]

- 1888: Thomas Edison and William Kennedy Dickson invents Kinetoscope.[415]

- 1888: Heinrich Hertz publishes a conclusive proof of James Clerk Maxwell's electromagnetic theory in experiments that also demonstrate the existence of radio waves. The effects of electromagnetic waves had been observed by many people before this but no usable theory explaining them existed until Maxwell.

- 1888: The first practical pneumatic tire was made by Scotsman John Boyd Dunlop, the patent was from 1847 by Robert William Thomson

1890s[edit]

- 1890s: Frédéric Swarts invents the first chlorofluorocarbons to be applied as refrigerant.[416]

- 1890: Robert Gair would invent the pre-cut cardboard box.[417]

- 1891: Whitcomb Judson invents the zipper.

- 1892: Léon Bouly invents the cinematograph.

- 1892: Thomas Ahearn invents the electric oven.[418]

- 1893: Rudolf Diesel invents the diesel engine (although Herbert Akroyd Stuart had experimented with compression ignition before Diesel).

- 1893: William Stewart Halsted, invents the rubber glove for his wife Caroline Hampton as he noticed her hands were affected on the daily surgeries she had performed and in order to prevent medical staff from developing dermatitis from surgical chemicals.[419][420][421] The first modern disposable glove was invented by Ansell Rubber Co. Pty. Ltd. in 1965.[422][423][424]

- 1895: Guglielmo Marconi invents a system of wireless communication using radio waves.

- 1895: Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen invented the first radiograph (xrays).

- 1897: Surgical masks made of cloth were developed in Europe by physicians Jan Mikulicz-Radecki at the University of Breslau and Paul Berger in Paris, as a result of increasing awareness of germ theory and the importance of antiseptic procedures in medicine.[425]

- 1898: Hans von Pechmann synthesizes polyethylene, now the most common plastic in the world.[426]

- 1899: Waldemar Jungner invents the rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery (NiCd) as well as the nickel-iron electric storage battery (NiFe) and the rechargeable alkaline silver-cadmium battery (AgCd)

20th century[edit]

1900s[edit]

- 1900: The first Zeppelin is designed by Theodor Kober.

- 1901: The first motorized cleaner using suction, a powered "vacuum cleaner", is patented independently by Hubert Cecil Booth and David T. Kenney.[427]

- 1903: The first successful gas turbine is invented by Ægidius Elling.

- 1903: Édouard Bénédictus invents laminated glass.

- 1903: First sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight achieved by an airplane flown at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina by Orville and Wilbur Wright. See Claims to the first powered flight.

- 1904: The Fleming valve, the first vacuum tube and diode, is invented by John Ambrose Fleming.

- 1907: The first free flight of a rotary-wing aircraft is carried out by Paul Cornu.

- 1907: Leo Baekeland invents bakelite, the first plastic made from synthetic components.

- 1907: The tuyères thermopropulsives[428] after 1945 (Maurice Roy (fr)) known as the statoreacteur[428][429] a combustion subsonique (the ramjet)[430] – R. Lorin[431][432][433]

- 1908: Cellophane is invented by Jacques E. Brandenberger.

- 1909: Fritz Haber invents the Haber process.

- 1909: The first instantaneous transmission of images, or television broadcast, is carried out by Georges Rignoux and A. Fournier.

1910s[edit]

- 1911: The cloud chamber, the first particle detector, is invented by Charles Thomson Rees Wilson.

- 1912: The first commercial slot cars or more accurately model electric racing cars operating under constant power were made by Lionel (USA) and appeared in their catalogues in 1912. They drew power from a toy train rail sunk in a trough that was connected to a battery.

- 1912: The first use of articulated trams by Boston Elevated Railway.

- 1913: The Bergius process is developed by Friedrich Bergius.

- 1913: The Kaplan turbine is invented by Viktor Kaplan.

- 1915: Harry Brearley invents a process to create Martensitic stainless steel, initially labelled Rustless Steel, later marketed as Staybrite, and AISI Type 420.[434]

- 1915: The first operational military tanks are designed in Great Britain and France. They are used in battle from 1916 and 1917 respectively. The designers in Great Britain are Walter Wilson and William Tritton and in France, Eugène Brillié. (Although it is known that vehicles incorporating at least some of the features of the tank were designed in a number of countries from 1903 onward, none reached a practical form.)

- 1916: The Czochralski process, widely used for the production of single crystal silicon, is invented by Jan Czochralski.

- 1917: The crystal oscillator is invented by Alexander M. Nicholson using a crystal of Rochelle Salt although his priority was disputed by Walter Guyton Cady.

1920s[edit]

- 1925: The Fischer–Tropsch process is developed by Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Kohlenforschung.

- 1926: The Yagi-Uda Antenna or simply Yagi Antenna is invented by Shintaro Uda of Tohoku Imperial University, assisted by his colleague Hidetsugu Yagi. The Yagi Antenna was widely used during World War II. After the war they saw extensive development as home television antennas.

- 1926: Robert H. Goddard launches the first liquid fueled rocket.

- 1926: Harry Ferguson, patents the Three-point hitch equipment linkage system for tractors.[435]

- 1926: John Logie Baird demonstrates the world's first live working television system.[436][437][438]

- 1927: The quartz clock is invented by Warren Marrison and J.W. Horton at Bell Telephone Laboratories.[439]

- 1928: Penicillin is first observed to exude antibiotic substances by Nobel laureate Alexander Fleming. Development of medicinal penicillin is attributed to a team of medics and scientists including Howard Walter Florey, Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley.

- 1928: Frank Whittle formally submitted his ideas for a turbo-jet engine. In October 1929, he developed his ideas further.[440] On 16 January 1930, Whittle submitted his first patent (granted in 1932).[441][442]

- 1928: Philo Farnsworth demonstrates the first practical electronic television to the press.

- 1929: The ball screw is invented by Rudolph G. Boehm.

1930s[edit]

- 1930: The Supersonic combusting ramjet — Frank Whittle.[443]

- 1930: The Phase-contrast microscopy is invented by Frits Zernike.

- 1931: The electron microscope is invented by Ernst Ruska.

- 1933: FM radio is patented by inventor Edwin H. Armstrong.

- 1933: Harry C. Jennings Sr. and his disabled friend Herbert Everest, both mechanical engineers, invented the first lightweight, steel, folding, portable wheelchair with their "X-brace" design.[444][445]

- 1935: Nylon, the first fully synthetic fiber is produced by Wallace Carothers while working at DuPont.[446]

- 1938: Z1, built by Konrad Zuse, is the first freely programmable computer in the world.

- 1938: Nuclear fission discovered in experiment by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. The German nuclear energy project was based on this research. The Tube Alloys project and, subsequently, the Manhattan Project and the Soviet atomic bomb project were influenced by this research.

- 1939: G. S. Yunyev or Naum Gurvich invented the electric current defibrillator

1940-1944[edit]

- 1940: Pu-239 isotope (isotope of plutonium)[447][448] a form of matter existing with the capacity for use as a destructive element[449] (because the isotope has an exponentially increasing[447] spontaneous[450] fissile decay[451]) within nuclear devices — Glenn Seaborg.[448]

- 1940: John Randall and Harry Boot would develop the high power, microwave generating, cavity magnetron, later applied to commercial Radar and Microwave oven appliances.[452]

- 1941: Polyester is invented by John Rex Whinfield and James Dickson.[453]

- 1942: The V-2 rocket, the world's first long range ballistic missile, developed by engineer Wernher von Braun.

- 1944: The non-infectious viral vaccine is perfected by Dr. Jonas Salk and Thomas Francis.[454]

Contemporary history[edit]

1945-1950[edit]

- 1945: The atomic bomb is developed by the Manhattan Project and swiftly deployed in August 1945 in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, effectively ending World War II.

- 1945: Percy Spencer, while employed at Raytheon, would patent a magnetron based microwave oven.[455]

- 1945: Willard Libby began his work on radiocarbon dating. He published his paper in 1946,[456][457] a second paper in Science in 1947.[456][458] Libby and James Arnold succeeded with the radiocarbon dating theory after results were published in Science in December 1949.[459][460]

- 1946: James Martin invents the ejector seat, inspired by the death of his friend and test pilot Captain Valentine Baker in an aeroplane crash in 1942.

- 1947: Holography is invented by Dennis Gabor.

- 1947: Floyd Farris and J.B. Clark (Stanolind Oil and Gas Corporation) invents hydraulic fracturing technology.[461]

- 1947: The first transistor, a bipolar point-contact transistor, is invented by John Bardeen and Walter Brattain under the supervision of William Shockley at Bell Labs.

- 1948: The first atomic clock is developed at the National Bureau of Standards.

- 1948: Basic oxygen steelmaking is developed by Robert Durrer. The vast majority of steel manufactured in the world is produced using the basic oxygen furnace; in 2000, it accounted for 60% of global steel output.[462]

1950s[edit]

- 1950: Bertie the Brain, debatably the first video game, is displayed to the public at the Canadian National Exhibition.

- 1950: The Toroidal chamber with axial magnetic fields (the Tokamak) is developed by Igor E. Tamm and Andrei D. Sakharov.[463]

- 1952: The float glass process is developed by Alastair Pilkington.[464]

- 1952: The first thermonuclear weapon is developed.

- 1953: The first video tape recorder, a helical scan recorder, is invented by Norikazu Sawazaki.

- 1954: Invention of the solar battery by Bell Telephone scientists, Calvin Souther Fuller, Daryl Chapin and Gerald Pearson capturing the Sun's power. First practical means of collecting energy from the Sun and turning it into a current of electricity.

- 1955: The hovercraft is patented by Christopher Cockerell.

- 1955: The intermodal container is developed by Malcom McLean.

- 1956: The hard disk drive is invented by IBM.[465]

- 1956: The Logic Theorist computer program, the first "artificial intelligence program", was written and invented by Allen Newell, Herbert A. Simon, and Cliff Shaw.[466]

- 1957: The laser and optical amplifier are invented and named by Gordon Gould and Charles Townes. The laser and optical amplifier are foundational to powering the Internet.[467]

- 1957: The first personal computer used by one person and controlled by a keyboard, the IBM 610, is invented in 1957 by IBM.

- 1957: The first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, is launched.

- 1958 – 1959: The integrated circuit is independently invented by Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce.

- 1959: The MOSFET (MOS transistor) is invented by the Egyptian Mohamed Atalla and the Korean Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs. It is used in almost all modern electronic products. It was smaller, faster, more reliable and cheaper to manufacture than earlier bipolar transistors, leading to a revolution in computers, controls and communication.[468][469][470]

1960s[edit]

- 1960: The first functioning laser is invented by Theodore Maiman.

- 1963: The first electronic cigarette is created by Herbert A. Gilbert. Hon Lik is often credited with its invention as he developed the modern electronic cigarette and was the first to commercialize it.

- 1964: Shinkansen, the first high-speed rail commercial passenger service.

- 1965: Kevlar is invented by Stephanie Kwolek at DuPont.

- 1969: ARPANET and the NPL network implement packet switching,[471][472] drawing on the concepts and designs of Donald Davies,[473][474] and Paul Baran.[475]

1970s[edit]

- 1970s: Public-key cryptography is invented and developed by James H. Ellis, Clifford Cocks, Malcolm J. Williamson, Whitfield Diffie, Martin Hellman, Ralph Merkle, Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, Leonard Adleman, et al.

- 1970: The pocket calculator is invented.

- 1971: The first single-chip microprocessor, the Intel 4004, is invented. Its development was led by Federico Faggin, using his silicon-gate MOS technology. This led to the personal computer (PC) revolution.[476]

- 1971: The first space station, Salyut 1, is launched.

- 1971: IBM developed and released the world's first floppy disk and disk drive.[477]

- 1972: The first video game console, used primarily for playing video games on a TV, is the Magnavox Odyssey.[478]

- 1973: The first fiber optic communication systems were developed by Optelecom.[479]

- 1973: The first commercial graphical user interface is introduced in 1973 on the Xerox Alto. The modern GUI is later popularized by the Xerox Star and Apple Lisa.

- 1973: The first capacitive touchscreen is developed at CERN.

- 1974: The Transmission Control Program is proposed by Vinton Cerf and Robert E. Kahn, building on the work of Louis Pouzin, creating the basis for the modern Internet.[480][481]

- 1974: The lithium-ion battery is invented by M. Stanley Whittingham, and further developed in the 1980s and 1990s by John B. Goodenough, Rachid Yazami and Akira Yoshino. It has impacted modern consumer electronics and electric vehicles.[482]

- 1974: The Rubik’s cube is invented by Ernő Rubik which went on the be the best selling puzzle ever.

- 1977: Dr Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger invented a new DNA sequencing method for which they won the Nobel Prize.[483]

- 1977: The first self-driving car that did not rely upon rails or wires under the road is designed by the Tsukuba Mechanical Engineering Laboratory.[484]

- 1978: The Global Positioning System (GPS) enters service. While not the first Satellite navigation system, it is the first to enter widespread civilian use.

- 1979: The first handheld game console with interchangeable game cartridges, the Microvision is released.

- 1979: Public dialup information, messaging and e-commerce services, were pioneered through CompuServe and RadioShack's MicroNET, and the UK's Post Office Telecommunications Prestel services.[485][486]

1980s[edit]

- 1980: Flash memory (both NOR and NAND types) is invented by Fujio Masuoka while working for Toshiba. It is formally introduced to the public in 1984.

- 1981: The first reusable spacecraft, the Space Shuttle undergoes test flights ahead of full operation in 1982.

- 1981: Kane Kramer develops the credit card sized, IXI digital media player.[487]

- 1982: A CD-ROM contains data accessible to, but not writable by, a computer for data storage and music playback. The 1985 Yellow Book standard developed by Sony and Philips adapted the format to hold any form of binary data.[488]

- 1982: Direct to home satellite television transmission, with the launch of Sky One service.[489]

- 1982: The first laptop computer is launched, the 8/16-bit Epson HX-20.[490]

- 1983: Stereolithography is invented by Chuck Hull.[491]

- 1984: The first commercially available cell phone, the DynaTAC 8000X, is created by Motorola.

- 1984: DNA profiling is pioneered by Alec Jeffreys.[492][493]

- 1989: Karlheinz Brandenburg would publish the audio compression algorithms that would be standardised as the: MPEG-1, layer 3 (mp3), and later the MPEG-2, layer 7 Advanced Audio Compression (AAC).[494]

- 1989: The World Wide Web is invented by computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee.[495][496]

1990s[edit]

- 1990: The Neo Geo AES becomes the first video game system to launch that used Memory Cards

- 1990: The first search engine invented was “Archie”, created by Alan Emtage a student at McGill University in Montreal

- 1991: The first commercial flash-based solid-state drive is launched by SunDisk.[497]

- 1991: The first sim card is developed by Munich smart-card maker Giesecke & Devrient,

- 1993: IBM created the first mobile app with SIMON, it had 10 bulit-in apps from Email to Calendar

- 1994: IBM Simon, World's first smartphone is developed by IBM.

- 1994: First generation of Bluetooth is developed by Ericsson Mobile. A form of data communication on short distances between electronic devices.

- 1994: A Tetris variant on the Hagenuk MT-2000 device becomes the first mobile game

- 1995: DVD is an optical disc storage format, invented and developed by Philips, Sony, Toshiba, and Panasonic in 1995. DVDs offer higher storage capacity than compact discs while having the same dimensions.

- 1995: Match.com launches as the first dating site ever and is the number 1 most visited dating site in the US

- 1995: Waiter.com launches as the first online food ordering service

- 1996: Ciena deploys the first commercial wave division multiplexing system in partnership with Sprint. This created the massive capacity of the internet.[498]

- 1996: Mobile web was first commercially offered in Finland on the Nokia 9000 Communicator phone and it was also the first phone with texting

- 1996: Bolt and Six Degrees (1997) both become the first social media sites

- 1997: The first weblog, a discussion or informational website, is created by Jorn Barger, later shortened to "blog" in 1999 by Peter Merholz.

- 1998: The first portable MP3 player is released by SaeHan Information Systems.

- 1999: The first digital video recorder (DVR), the TiVo, is launched by Xperi.

- 1999: NTT DoCoMo launches i-mode, the first integrated Online App store for mobile phones

21st century[edit]

2000s[edit]

- 2000: Sony develops the first prototypes for the Blu-ray optical disc format. The first prototype player was released in 2004.

- 2000: First documented placement of Geocaching, an outdoor recreational activity, in which participants use a Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver or mobile device and other navigational techniques to hide and seek containers, took place on May 3, 2000, by Dave Ulmer of Beavercreek, Oregon.

- 2001: The Xbox Launches and is the first game console with internal storage

- 2004: First podcast, invented by Adam Curry and Dave Winer, is a program made available in digital format for download over the Internet and it usually features one or more recurring hosts engaged in a discussion about a particular topic or current event.[499][500][501]

- 2005: YouTube, the first popular video-streaming site, was founded

- 2007: Netflix debuted the first popular video-on-demand service

- 2007: Apple Inc. released the iPhone

- 2007: The Bank of Scotland develops the worlds first banking app

- 2007: SoundCloud, the first on-demand service to focus on music is debuted

- 2007: First Kindle introduced by Amazon (company) founder and CEO Jeff Bezos, who instructed the company's employees to build the world's best e-reader before Amazon's competitors could. Amazon originally used the codename Fiona for the device. This hardware evolved from the original Kindle introduced in 2007 and the Kindle DX (with its larger 9.7" screen) introduced in 2009.[502]

- 2008: Satoshi Nakamoto develops the first blockchain.[503]

2010s[edit]

- 2010: The first solar sail based spacecraft, IKAROS.[504]

- 2010: The first quantum machine[505]

- 2010: The first synthetic organism, Mycoplasma laboratorium is created by the J. Craig Venter Institute.

- 2011: Twitch, launches as the first live-streaming service.

- 2011: HIV treatment as prevention (HPTN 052)[506]

- 2012: Discovery of the Higgs boson[507]

- 2013: Cancer immunotherapy[508]

- 2014: The first known "NFT", Quantum,[509] was created by Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash in May 2014, that explicitly linked a non-fungible, tradable blockchain marker to a work of art, via on-chain metadata (enabled by Namecoin).[510]

- 2015: CRISPR genome-editing method[511]

- 2016: The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory makes the first observation of gravitational waves, fulfilling Einstein's prediction[512]

- 2018: Single cell sequencing[513]

- 2019: IBM launches IBM Q System One, its first integrated quantum computing system for commercial use.

2020s[edit]

- 2020: The first RNA vaccine to be approved by public health medicines regulators is co-developed by Pfizer and BioNTech for COVID-19.

- 2022: Pfizer develops the world's first pill for COVID.

See also[edit]

- Accelerating change

- List of emerging technologies

- List of inventors

- List of years in science

- Outline of prehistoric technology

- Timeline of prehistory

- By type

- History of communication

- Timeline of agriculture and food technology

- Timeline of electrical and electronic engineering

- Timeline of transportation technology

- Timeline of heat engine technology

- Timeline of rocket and missile technology

- Timeline of motor and engine technology

- Timeline of steam power

- Timeline of temperature and pressure measurement technology

- Timeline of mathematics

- Timeline of computing

Notes[edit]

- ^ Dates for inventions are often controversial. Sometimes inventions are invented by several inventors around the same time, or may be invented in an impractical form many years before another inventor improves the invention into a more practical form. Where there is ambiguity, the date of the first known working version of the invention is used here.

- ^ Earthen pipes were later used in the Indus Valley c. 2700 BC for a city-scale urban drainage system,[105] and more durable copper drainage pipes appeared in Egypt, by the time of the construction of the Pyramid of Sahure at Abusir, c.2400 BCE.[106]

- ^ Shell, Terracotta, Copper, and Ivory rulers were in use by the Indus Valley civilisation in what today is Pakistan, and North West India, prior to 1500 BCE.[147]

- ^ A competing claim is from Lothal dockyard in India,[155][156][157][158][159] constructed at some point between 2400-2000 BC;[160] however, more precise dating does not exist.

- ^ the uncertainty in dating several Indian developments between 600 BC and 300 AD, due to the tradition that existed of editing existing documents (such as the Sushruta Samhita and Arthashastra) without specifically documenting the edit. Most such documents were canonized at the start of the Gupta empire (mid-3rd century AD).

- ^ A 10th century AD, Damascus steel blade, analysed under an electron microscope, contains nano-meter tubes in its metal alloy. Their presence has been suggested to be down to transition-metal impurities in the ores once used to produce Wootz Steel in South India.[195]

- ^ Although it is recorded that the Han Dynasty (202 BC – AD 220) court eunuch Cai Lun (born c. 50–121 AD) invented the pulp papermaking process and established the use of new raw materials used in making paper, ancient padding and wrapping paper artifacts dating to the 2nd century BC have been found in China, the oldest example of pulp papermaking being a map from Fangmatan, Gansu.[244]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ De Heinzelin, J; Clark, JD; White, T; Hart, W; Renne, P; Woldegabriel, G; Beyene, Y; Vrba, E (1999). "Environment and behavior of 2.5-million-year-old Bouri hominids". Science. 284 (5414): 625–9. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..625D. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.625. PMID 10213682.

- ^ Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy (2009), "African Origins", in Scarre, Chris (ed.), The Human Past: World Prehistory and the Development of Human Societies (2nd ed.), London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 67–68

- ^ "Invention of cooking drove evolution of the human species, new book argues". harvard.edu. 1 June 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Until the Wonderwerk Cave find, Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, a lakeside site in Israel, was considered to have the oldest generally accepted evidence of human-controlled fire".

- ^ James, Steven R. (February 1989). "Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 30 (1). University of Chicago Press: 1–26. doi:10.1086/203705. S2CID 146473957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Anthropologists have yet to find an Acheulian hand axe gripped in a Homo erectus fist but most credit Homo erectus with developing the technology."

- ^ Lepre, Christopher J.; Roche, Hélène; Kent, Dennis V.; Harmand, Sonia; Quinn, Rhonda L.; Brugal, Jean-Philippe; Texier, Pierre-Jean; Lenoble, Arnaud; Feibel, Craig S. (2011). "An earlier origin for the Acheulian". Nature. 477 (7362): 82–85. Bibcode:2011Natur.477...82L. doi:10.1038/nature10372. PMID 21886161. S2CID 4419567.

- ^ Uomini, Natalie Thaïs; Meyer, Georg Friedrich (30 August 2013). Petraglia, Michael D. (ed.). "Shared Brain Lateralization Patterns in Language and Acheulean Stone Tool Production: A Functional Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound Study". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e72693. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872693U. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072693. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3758346. PMID 24023634.

- ^ Perreault, C.; Mathew, S. (2012). "Dating the origin of language using phonemic diversity". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35289. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735289P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035289. PMC 3338724. PMID 22558135.

- ^ "Early humans make bone tools". Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. 17 February 2010. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Plakias Survey Finds Mesolithic and Palaeolithic Artifacts on Crete". www.ascsa.edu.gr. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ First Mariners – Archaeology Magazine Archive. Archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved on 16 November 2013.

- ^ Wilkins, J.; Schoville, B. J.; Brown, K. S.; Chazan, M. (15 November 2012). "Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology". Science. 6109. 338 (6109): 942–946. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..942W. doi:10.1126/science.1227608. PMID 23161998. S2CID 206544031.

- ^ Barham, L.; Duller, G.A.T.; Candy, I.; et al. (2023). "Evidence for the earliest structural use of wood at least 476,000 years ago". Nature. 622 (7981): 107–111. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06557-9. PMID 37730994.

- ^ "BBC News – SCI/TECH – Earliest evidence of art found". BBC News. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Kouwenhoven, Arlette P., World's Oldest Spears

- ^ Richter, D.; Krbetschek, M. (2015). "The age of the Lower Paleolithic occupation at Schöningen". Journal of Human Evolution. 89: 46–56. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.06.003. PMID 26212768.

- ^ Chatterjee, Rhitu (15 March 2018). "Scientists Are Amazed By Stone Age Tools They Dug Up In Kenya". NPR. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Yong, Ed (15 March 2018). "A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity - New finds from Kenya suggest that humans used long-distance trade networks, sophisticated tools, and symbolic pigments right from the dawn of our species". The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts R, Behrensmeyer AK, Deino AL, Leslie DE, Ambrose SH, Ferguson JR, d'Errico F, Zipkin AM, Whittaker S, Post J, Veatch EG, Foecke K, Clark JB (2018). "Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age". Science. 360 (6384): 90–94. Bibcode:2018Sci...360...90B. doi:10.1126/science.aao2646. PMID 29545508.

- ^ Sahle, Y.; Hutchings, W. K.; Braun, D. R.; Sealy, J. C.; Morgan, L. E.; Negash, A.; Atnafu, B. (2013). Petraglia, Michael D (ed.). "Earliest Stone-Tipped Projectiles from the Ethiopian Rift Date to >279,000 Years Ago". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e78092. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878092S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078092. PMC 3827237. PMID 24236011.

- ^ Schmidt, P.; Blessing, M.; Rageot, M.; Iovita, R.; Pfleging, J.; Nickel, K. G.; Righetti, L.; Tennie, C. (2019). "Birch tar extraction does not prove Neanderthal behavioral complexity". PNAS. 116 (36): 17707–17711. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11617707S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1911137116. PMC 6731756. PMID 31427508.

- ^ Wadley, L; Hodgskiss, T; Grant, M (June 2009). "Implications for complex cognition from the hafting of tools with compound adhesives in the Middle Stone Age, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (24): 9590–4. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9590W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900957106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2700998. PMID 19433786.

- ^ Wadley, Lyn (1 June 2010). "Compound-Adhesive Manufacture as a Behavioral Proxy for Complex Cognition in the Middle Stone Age". Current Anthropology. 51 (s1): S111–S119. doi:10.1086/649836. S2CID 56253913.

- ^ "200,000 years ago, humans preferred to sleep in beds". phys.org. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "The oldest known grass beds from 200,000 years ago included insect repellents". Science News. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Wadley, Lyn; Esteban, Irene; Peña, Paloma de la; Wojcieszak, Marine; Stratford, Dominic; Lennox, Sandra; d'Errico, Francesco; Rosso, Daniela Eugenia; Orange, François; Backwell, Lucinda; Sievers, Christine (14 August 2020). "Fire and grass-bedding construction 200 thousand years ago at Border Cave, South Africa". Science. 369 (6505): 863–866. Bibcode:2020Sci...369..863W. doi:10.1126/science.abc7239. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 32792402. S2CID 221113832. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Toups, M. A.; Kitchen, A.; Light, J. E.; Reed, D. L. (2011). "Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28: 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. PMC 3002236. PMID 20823373.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (1 February 2016). "The History of Clothing – How Did Specific Items of Clothing Develop?". The About Group. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ Brown, K. S.; Marean, C. W.; Herries, A. I. R.; Jacobs, Z.; Tribolo, C.; Braun, D.; Roberts, D. L.; Meyer, M. C.; Bernatchez, J. (2009). "Fire As an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans". Science. 325 (5942): 859–862. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..859B. doi:10.1126/science.1175028. hdl:11422/11102. PMID 19679810. S2CID 43916405.

- ^ Vanhaereny, M.; d'Errico, Francesco; Stringer, Chris; James, Sarah L.; Todd, Jonathan A.; Mienis, Henk K. (2006). "Middle Paleolithic Shell Beads in Israel and Algeria". Science. 312 (5781): 1785–1788. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1785V. doi:10.1126/science.1128139. PMID 16794076. S2CID 31098527.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (13 October 2011). "A Cultural Leap at the Dawn of Humanity - Ancient 'paint factory' unearthed". BBC News. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Vastag, Brian (13 October 2011). "South African cave yields paint from dawn of humanity". Washington Post. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Henshilwood, Christopher S.; et al. (2011). "A 100,000-Year-Old Ochre-Processing Workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa". Science. 334 (6053): 219–222. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..219H. doi:10.1126/science.1211535. PMID 21998386. S2CID 40455940.

- ^ Lieberman, Philip (1993). Uniquely Human page 163. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674921832. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Yellen, JE; AS Brooks; E Cornelissen; MJ Mehlman; K Stewart (28 April 1995). "A middle stone age worked bone industry from Katanda, Upper Semliki Valley, Zaire". Science. 268 (5210): 553–556. Bibcode:1995Sci...268..553Y. doi:10.1126/science.7725100. PMID 7725100.