Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

1780s[edit]

1789: The Constitution of the United States grants the states the power to set voting requirements. Generally, states limited this right to property-owning or tax-paying white males (about 6% of the population).[1] However, New Jersey also gave the vote to unmarried and widowed women who met the property qualifications, regardless of color. Married women were not allowed to own property and hence could not vote.[2][3]

1800s[edit]

1807: Voting rights are taken away from women in New Jersey.[2]

1830s[edit]

1838: Kentucky passes the first statewide woman suffrage law allowing female heads of household in rural areas to vote in elections deciding on taxes and local boards for the new county "common school" system.[4]

1840s[edit]

1848: New York. Women's suffrage was proposed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and agreed to after an impassioned argument from Frederick Douglass.

1850s[edit]

1850: The first National Woman's Rights Convention, in Worcester, Massachusetts, attracted more than 1,000 participants from 11 states.[5]

1853: On the occasion of the World's Fair in New York City, suffragists hold a meeting in the Broadway Tabernacle.[3]

1860s[edit]

1861–1865: The American Civil War. Most suffragists focus on the war effort, and suffrage activity is minimal.[3]

1866: The American Equal Rights Association, working for suffrage for both women and African Americans, is formed at the initiative of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.[6]

1867: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone address a subcommittee of the New York State Constitutional Convention requesting that the revised constitution include woman suffrage. Their efforts fail.[citation needed]

1867: Kansas holds a state referendum on whether to enfranchise women and/or black men. Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton traverse the state speaking in favor of white women's suffrage. Both women's and black men's suffrage is voted down.[7]

1868: The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is ratified, introducing the word "male" into the Constitution for the first time, in Section 2 of the amendment. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Parker Pillsbury published the first edition of The Revolution. This periodical carries the motto “Men, their rights and nothing more; women, their rights and nothing less!” Caroline Seymour Severance establishes the New England Woman’s Club. The “Mother of Clubs” sparked the club movement which became popular by the late nineteenth century. In Vineland, New Jersey, 172 women cast ballots in a separate box during the presidential election. Senator S.C. Pomeroy of Kansas introduces the federal woman’s suffrage amendment in Congress. Many early suffrage supporters, including Susan B. Anthony, remained single because, in the mid-1800s, married women could not own property in their rights and could not make legal contracts on their own behalf. The Fourteenth Amendment is ratified. "Citizens" and "voters" are defined exclusively as male.[citation needed]

1869: The territory of Wyoming is the first to grant unrestricted suffrage to women.[3]

1869: The suffrage movement splits into the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association. The NWSA is formed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony after their accusing abolitionist and Republican supporters of emphasizing black civil rights at the expense of women's rights. The AWSA is formed by Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and it protests the confrontational tactics of the NWSA and ties itself closely to the Republican Party while concentrating solely on securing the vote for women state by state.[8] Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the first president of the National Woman Suffrage Association.[9] Julia Ward Howe was the first president of the American Woman Suffrage Association.[10]

1869: The Anti-Sixteenth Amendment Society is formed.[11]

1870s[edit]

1870: The Utah Territory grants suffrage to women.[7]

1870: The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is adopted. The amendment holds that neither the United States nor any State can deny the right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude," leaving open the right of States to deny the right to vote on account of sex. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton oppose the amendment. Many of their former allies in the abolitionist movement, including Lucy Stone, support the amendment.[7]

1871: Victoria Woodhull speaks to the Judiciary Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, arguing that women have the right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but the committee does not agree.[7]

1871: The Anti-Suffrage Society is formed.[6]

1872: A suffrage proposal before the Dakota Territory legislature loses by one vote.[3]

1872: Susan B. Anthony registers and votes in Rochester, New York, arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gives her that right. However, she is arrested a few days later.[7] Victoria Woodhull was the first female to run for President of the United States, nominated by the Equal Rights Party, with a platform supporting women's suffrage and equal rights.

1873: The trial of Susan B. Anthony is held. She is denied a trial by jury and loses her case. She never pays the $100 fine for voting.

1873: There is a suffrage demonstration at the Centennial of the Boston Tea Party.[6]

1875: In the case of Minor v. Happersett, the Supreme Court rules that the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution does not grant women the right to vote.[3]

1874: There is a referendum in Michigan on women's suffrage, but women's suffrage loses.[3]

1875: Women in Michigan and Minnesota win the right to vote in school elections.[3]

1878: A federal amendment to grant women the right to vote is introduced for the first time by Senator Aaron A. Sargent of California. Though initially unsuccessful, the amendment would eventually become the 19th Amendment.[3][12]

1880s[edit]

1880: New York state grants school suffrage to women.[7]

1882: The U.S. House and Senate both appoint committees on women's suffrage, which both report favorably.[6]

1883: Women in the Washington territory are granted full voting rights.[3]

1884: The U.S. House of Representatives debates women's suffrage.[6]

1886: The suffrage amendment is defeated two to one in the U.S. Senate.[6]

1887: The Edmunds–Tucker Act takes the vote away from women in Utah in order to suppress the Mormon vote in the Utah territory.[6]

1887: The Supreme Court strikes down the law that enfranchised women in the Washington territory.[3]

1887: In Kansas, women win the right to vote in municipal elections.[3]

1887: Rhode Island becomes the first eastern state to vote on a women's suffrage referendum, but it does not pass.[3]

1888–1889: Wyoming had already granted women voting and suffrage since 1869–70; now they insist that they maintain suffrage if Wyoming joins the Union.

1890s[edit]

1890: The National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association merge to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Its first president is Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The focus turns to working at the state level. Wyoming renewed general women's suffrage, becoming the first state to allow women to vote.[6][3][8]

1890: A suffrage campaign loses in South Dakota.[6]

1893: After a campaign led by Carrie Chapman Catt, Colorado men vote for women's suffrage.[6]

1894: Despite 600,000 signatures, a petition for women's suffrage is ignored in New York.[6]

1895: The New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage begins.[3]

1895: The National American Woman Suffrage Association dissociates itself from Elizabeth Cady Stanton's The Woman's Bible, a critique of Christianity.[3]

1896: Women's suffrage returns to Utah upon gaining statehood.[6][13]

1896: The National American Woman Suffrage Association hires Ida Husted Harper to launch an expensive suffrage campaign in California, which ultimately fails.[3]

1896: Idaho grants women suffrage.[6]

1897: The National American Woman Suffrage Association begins publishing the National Suffrage Bulletin, edited by Carrie Chapman Catt.[3]

1900s[edit]

1902: Women from 10 nations meet in Washington, D.C., to plan an international effort for suffrage. Clara Barton is among the speakers.[3]

1902: The men of New Hampshire vote down a women's suffrage referendum.[3]

1904: The National American Woman Suffrage Association adopts a Declaration of Principles.[6]

1904: Because Carrie Chapman Catt must attend to her dying husband, Rev. Dr. Anna Howard Shaw takes over as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.[3]

1906: Elizabeth Cady Stanton's daughter, Harriot Stanton Blatch, returns from England and forms the Equality League of Self Supporting Women with a membership based on professional and industrial working women. It initiates the practice of holding suffrage parades.[14]

1908: The first suffrage march in the United States is held in Oakland, California, on August 27, co-led by Johanna Pinther of San Francisco's Glen Park, her step-daughter-in-law Jeanette Pinther of Noe Valley, San Francisco,[15] and Lillian Harris Coffin[16] of Marin County, California. Followed by as many as 300 women, they carried the banner[17] for the California Equal Suffrage Association[18] hand-sewn and embroidered by Johanna Pinther. The women marched nearly a mile along Broadway in Oakland to the site of the California State Republican Convention to demand California suffrage be added to the Republican platform (state Democratic and Labor parties had already done so). California Republicans would not add suffrage until their next state convention in 1909.[19]

1910s[edit]

1910: Emma Smith DeVoe organizes a grassroots campaign in Washington State, where women win suffrage.[3]

1910: Harriet Stanton Blatch's Equality League changes its name to the Women's Political Union.[3]

1910: Emulating the grassroots tactics of labor activists, the Women's Political Union organizes America's first large-scale suffrage parade, which is held in New York City.[3]

1910: Washington grants women the right to vote.[20]

1911: California grants women suffrage.[6]

1911: In New York City, 3,000 people march for women's suffrage.[6]

1912: Theodore Roosevelt's Progressive Party includes women's suffrage in its platform.[6]

1912: Abigail Scott Duniway dissuades members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from involving themselves in Oregon's grassroots suffrage campaign; Oregon women win the vote.[3]

1912: Arizona grants women suffrage.[6]

1912: Kansas grants women suffrage.[6]

1913: Alice Paul becomes the leader of the Congressional Union (CU), a militant branch of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.[3]

1913: Alice Paul organizes the Woman's Suffrage Procession, a parade in Washington, D.C., on the eve of Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. It is the largest suffrage parade to date. The parade is attacked by a mob, and hundreds of women are injured but no arrests are made.[6][3][21]

- Alice Paul, American suffragette

- Cover to the program for the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession which Alice Paul organized

- Head of the Woman Suffrage Procession with herald Inez Milholland at the front.

1913: The Alaskan Territory grants white and Black women suffrage.[6][22]

1913: Illinois grants municipal and presidential but not state suffrage to women.[6]

1913: Kate Gordon organizes the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference, where suffragists plan to lobby state legislatures for laws that will enfranchise white women only.[3]

1913: The Senate votes on a women's suffrage amendment, but it does not pass.[3]

1914: Nevada grants women suffrage.[3]

1914: Montana grants women suffrage.[3]

1914: The Congressional Union alienates leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association by campaigning against anti-suffrage Democrats in the congressional elections.[3]

1915: Carrie Chapman Catt replaces Anna Howard Shaw as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, partly due to the constant turmoil on the National Board caused by Shaw's lack of administrative expertise.[23]

1916: Alice Paul and others break away from the National American Woman Suffrage Association and form the National Woman's Party.[6]

1916: Woodrow Wilson promises that the Democratic Party Platform will endorse women's suffrage.[3]

1916: Montana elects suffragist Jeannette Rankin to the House of Representatives.[3] She is the first woman elected to the U.S. Congress.[24]

1917: Beginning in January, the National Woman's Party posts silent "Sentinels of Liberty," also known as the Silent Sentinels, at the White House. They are the first group to picket the White House. In June, the arrests begin. Nearly 500 women are arrested, and 168 serve jail time.[6][25][26]

November 14, 1917: The "Night of Terror" occurs at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia, in which suffragist prisoners are beaten and abused.[27]

1917: The U.S. enters W.W.I. Under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, the National American Woman Suffrage Association aligns itself with the war effort in order to gain support for women's suffrage.[3]

1917: Arkansas grants women the right to vote in primary, but not general elections.[3]

1917: Rhode Island grants women presidential suffrage.[6]

1917: The New York state constitution grants women suffrage.[6] New York is the first Eastern state to fully enfranchise women.[3]

1917: The Oklahoma state constitution grants women suffrage.[6]

1917: The South Dakota state constitution grants women suffrage.[6]

1918: The jailed suffragists are released from prison. An appellate court rules all the arrests were illegal.[6]

1918: The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which eventually granted women suffrage, passes the U.S. House with exactly a two-thirds vote but loses by two votes in the Senate. Jeannette Rankin opens debate on it in the House, and President Wilson addresses the Senate in support of it.[6][3]

1918: President Wilson declares his support for women's suffrage.[6]

1918: Women in Texas earn the right to vote in primary elections.[28]

1919: Michigan grants women full suffrage.[3]

1919: Oklahoma grants women full suffrage.[3]

1919: South Dakota grants women full suffrage.[3]

1919: The National American Woman Suffrage Association holds its convention in St. Louis, where Carrie Chapman Catt rallies to transform the association into the League of Women Voters.[3]

1919: In January, the National Women's Party lights and guards a "Watchfire for Freedom." It is maintained until the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution passes the U.S. Senate on June 4.[6]

1920s[edit]

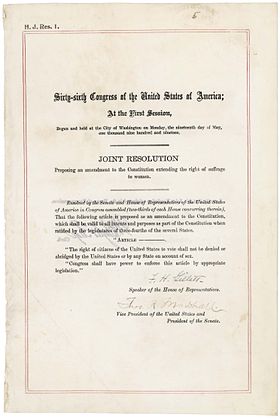

1920: The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is ratified, stating:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[29]

1920: In the case of Hawke v. Smith, anti-suffragists file suit against the Ohio legislature, but the Supreme Court upholds the constitutionality of Ohio's ratification process.[3]

1922: Fairchild v. Hughes, 258 U.S. 126 (1922),[30] is a case in which the Supreme Court held that a general citizen, in a state that already had women's suffrage, lacked standing to challenge the validity of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. A companion case, Leser v. Garnett upheld the ratification.[31][32][33]

1922: Leser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130 (1922),[34] is a case in which the Supreme Court held that the Nineteenth Amendment had been constitutionally established.

1924: Native American women played a vital role in passing the Nineteenth Amendment, but are still unable to reap the benefits until four years later on June 2, 1924, when the American government grants citizenship to Native Americans through the Indian Citizenship Act.[35] However, many states nonetheless make laws and policies which prohibit Native Americans from voting, and many are effectively barred from voting until 1948.[36]

1940s[edit]

1943: Chinese immigrants are no longer barred from becoming US citizens with the passage of the Magnuson Act, allowing some Chinese immigrants, including women, to become naturalized and gain the right to vote.

1950s[edit]

1952: The race restrictions of the 1790 Naturalization Law are repealed by the McCarran-Walter Act, giving first generation Japanese Americans, including women, citizenship and voting rights.

1960s[edit]

1964: The Twenty-fourth Amendment is ratified by three-fourths of the states, formally abolishing poll taxes and literacy tests which were heavily used against African-American and poor white women and men.

1965: The Voting Rights Act of 1965 strenuously prohibits racial discrimination in voting, resulting in greatly-increased voting by African American women and men.

1966: Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections strikes down poll taxes at all levels of government.

1980s[edit]

1984: Mississippi becomes the last state in the union to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.[37]

See also[edit]

- African-American women's suffrage movement

- Native Americans and women's suffrage in the United States

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Alabama

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Alaska

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Arizona

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Arkansas

- Timeline of women's suffrage in California

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Colorado

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Delaware

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Florida

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Hawaii

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Illinois

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Iowa

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Maine

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Missouri

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Montana

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Nevada

- Timeline of women's suffrage in New Jersey

- Timeline of women's suffrage in New Mexico

- Timeline of women's suffrage in North Dakota

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Ohio

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Pennsylvania

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Rhode Island

- Timeline of women's suffrage in South Dakota

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Texas

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Utah

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Virginia

- Timeline of women's suffrage in Wisconsin

- Timeline of voting rights in the United States

- Timeline of women's legal rights in the United States (other than voting)

- Timeline of women's suffrage worldwide

- Women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage in states of the United States

- Women's suffrage in the United States

References[edit]

- ^ "Expansion of Rights and Liberties - The Right of Suffrage". Online Exhibit: The Charters of Freedom. National Archives. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Klinghoffer, Judith Apter; Elkis, Lois (1992). "'The Petticoat Electors': Women's Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776-1807". Journal of the Early Republic. 12 (2): 159–193. doi:10.2307/3124150. JSTOR 3124150.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq "A History of the American Suffragist Movement". The Moschovitis Group. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ ""An Act to establish a system of Common Schools in the State of Kentucky" Chap. 898". Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Frankfort, KY: A.G. Hodges State Printer. December 1837. p. 282.

- ^ "First National Woman's Rights Convention Ends in Worcester". Mass Moments. The Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "The Woman Suffrage Timeline". The Liz Library. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "US Suffrage Movement Timeline, 1792 to present". Anthony Center for Women's Leadership at the University of Rochester. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "Teaching With Documents: Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Daniel Coit Gilman; Harry Thurston Peck; Frank Moore Colby (1904). The New International Encyclopaedia, Volume 16. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 188. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Catherine Clinton; Christine A. Lunardini (2000). The Columbia Guide to American Women in the Nineteenth Century. Columbia University Press. p. 179. ISBN 9780231109208. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Conkling, Winifred (2018). Votes for Women!: American Suffragists and the Battle for the Ballot. New York: Algonquin. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-61620-769-4.

- ^ Scott, Anne Firor; Scott, Andrew MacKay (1982). One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage. University of Illinois Press. p. 68. ISBN 9780252010057. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

sargent amendment.

- ^ "Constitution of the State of Utah (Article IV Section 1)". 1896-01-04.

- ^ Flexner, Eleanor, Century of Struggle, (1959), pp. 242–51. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674106536

- ^ "Noe Valley History - FoundSF". www.foundsf.org. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "Biographical Sketch of Lillian Harris Coffin | Alexander Street Documents". documents.alexanderstreet.com. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "Glen Park and the First Suffrage March". Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "WOMEN CLAIM THE VOTE IN CALIFORNIA - FoundSF". www.foundsf.org. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "Glen Park Resident Johanna Pinther and the First March for Suffrage in the United States". Glen Park Neighborhoods History Project. March 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "The History of Voting and Elections in Washington State". Secstate.wa.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ "Chronology of Woman Suffrage Movement Events". Scholastic Corporation. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Alaska and the 19th Amendment". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- ^ Scott, Anne Firor and Scott, Andrew MacKay (1982), One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage, pp. 25, 31. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01005-1

- ^ "Jeannette Rankin". United States House of Representatives - Office of Art & Archives. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Woodrow Wilson: Women's Suffrage". PBS. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "PSI Source: National Woman's Party". McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Night of Terror Leads to Women's Vote in 1917". Women's eNews. 30 October 2004. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Votes for Women! - The Battle Lost and Won - Page 2". Texas State Library | TSLAC. Retrieved 2020-08-15.

- ^ "19th Amendment". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ Fairchild v. Hughes, 258 U.S. 126 (1922).

- ^ Vile, John R. (2003-05-01). Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues: 1789-2002. ABC-CLIO. pp. 184–. ISBN 9781851094288. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Bradeis, Louis D. (1978-06-30). Letters of Louis D. Brandeis: 1921-1941, Elder statesman: 1921-1941. SUNY Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 9780873953306. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Renstrom, Peter G. (2003). The Taft Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 111–. ISBN 9781576072806. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Leser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130 (1922).

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document. - ^ Cahill, Cathleen D.; Deer, Sarah (2020-08-19). "In 1920, Native Women Sought the Vote. Here's What's Next". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- ^ Cahill, Cathleen D. (26 July 2020). "Suffrage in Spanish: Hispanic Women and the Fight for the 19th Amendment in New Mexico - Ms. Magazine". Ms. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- ^ Payne, Elizabeth Anne; Swain, Martha H. (2003), "The twentieth century", in Payne, Elizabeth Anne; Swain, Martha H.; Spruill, Majorie Julian (eds.), Mississippi women: their histories, their lives (volume 2), Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, p. 154, ISBN 9780820333939. Preview.

External links[edit]

- Woman's Suffrage History Timeline from the Women's Rights National Historic Park in Seneca Falls, NY

- One Hundred Years toward Suffrage: An Overview, a timeline from the Library of Congress.