World Christianity

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

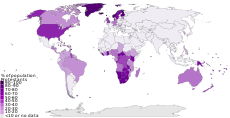

World Christianity or global Christianity has been defined both as a term that attempts to convey the global nature of the Christian religion[1][2][3] and an academic field of study that encompasses analysis of the histories, practices, and discourses of Christianity as a world religion and its various forms as they are found on the six continents.[4] However, the term often focuses on "non-Western Christianity" which "comprises (usually the exotic) instances of Christian faith in 'the global South', in Asia, Africa, and Latin America."[5] It also includes Indigenous or diasporic forms of Christianity in the Caribbean,[6] South America,[6] Western Europe,[7] and North America.[7]

History of the term[edit]

The term world Christianity can first be found in the writings of Francis John McConnell in 1929 and Henry P. Van Dusen in 1947.[10][11] Van Dusen was also instrumental in establishing the Henry W. Luce Visiting Professorship in World Christianity at Union Theological Seminary in 1945, with Francis C. M. Wei invited as its first incumbent.[12] The term would likewise be used by the American historian and Baptist missionary Kenneth Scott Latourette, Professor of the History of Christianity at Yale Divinity School, to speak of the "World Christian Fellowship" and "World Christian Community".[13][14] For these individuals, world Christianity was meant to promote the idea of Christian missions and ecumenical unity. However, after the end of World War II, as Christian missions ended in many countries, such as North Korea and China, and parts of Asia and Africa shifted due to decolonization and national independence, these aspects of world Christianity were largely lost.[15]

The current usage of the term puts much less emphasis in missions and ecumenism.[15] A number of historians have noted a twentieth-century "global shift" in Christianity, from a religion largely found in Europe and the Americas to one which is found in the Global South and Third World countries.[2][3][8][9][16] Hence, world Christianity has more recently been used to describe the diversity and the multiplicity of Christianity across its two-thousand-year history.[15]

Another term that is often used as analogous to world Christianity is the term global Christianity. However, scholars such as Lamin Sanneh have argued that global Christianity refers to a Eurocentric understanding of Christianity that emphasizes the replication of Christian forms and patterns in Europe, whereas world Christianity refers to the multiplicity of Indigenous responses to the Christian gospel.[17] Philip Jenkins and Graham Joseph Hill contend that Sanneh's distinction between world Christianity and global Christianity is artificial and unnecessary.[18][19]

Notable figures[edit]

Some notable figures in the academic study of world Christianity include Andrew Walls,[20] Lamin Sanneh,[21] and Brian Stanley,[22] all three of whom are associated with the "Yale-Edinburgh Group on the History of the Missionary Movement and World Christianity".[23] More recently, Klaus Koschorke and the “Munich School” of World Christianity has been highlighted for its contribution in understanding the polycentric nature of world Christianity.[24]

In contrast to these historians, there is a growing number of theologians who have been engaging the field of world Christianity from the discipline of systematic theology, ecclesiology, and missiology. Some examples of this include the Pentecostal Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, Catholic Peter C. Phan, and the Baptist Graham Joseph Hill.[25][26][27][28]

See also[edit]

- Acculturation

- Afro-Brazilian religions

- Catholic Church and the Age of Discovery

- Cultural assimilation

- Inculturation

- Indigenous church mission theory

- Latin American liberation theology

- Missiology

- Native American people and Mormonism

- Neo-charismatic movement

- Political influence of Evangelicalism in Latin America

- Prosperity theology

- Reverse mission

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Translations of the Bible

- Yale-Edinburgh Group

References[edit]

- ^ Barreto, Raimundo C. (2021). "Decoloniality and Interculturality in World Christianity: A Latin American Perspective". In Frederiks, Martha; Nagy, Dorottya (eds.). World Christianity: Methodological Considerations. Theology and Mission in World Christianity. Vol. 19. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 65–91. doi:10.1163/9789004444867_005. ISBN 978-90-04-44486-7. ISSN 2452-2953. JSTOR j.ctv1sr6jvr.7. S2CID 234580589.

- ^ a b c Jenkins, Philip (2011). "The Rise of the New Christianity". The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 101–133. ISBN 9780199767465. LCCN 2010046058.

- ^ a b c Robert, Dana L. (April 2000). Hastings, Thomas J. (ed.). "Shifting Southward: Global Christianity Since 1945" (PDF). International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 24 (2). SAGE Publications on behalf of the Overseas Ministries Study Center: 50–58. doi:10.1177/239693930002400201. ISSN 0272-6122. S2CID 152096915. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Bonk, Jonathan J. (20 December 2014). "Why "World" Christianity?". Boston: The Center for Global Christianity and Mission at the Boston University School of Theology. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Kim, Sebastian; Kim, Kirsteen (2008). "Christianity as a World Religion". Christianity as a World Religion. London and New York: Continuum International. pp. 1–22. doi:10.5040/9781472548894.ch-001. ISBN 978-1-4725-4889-4. S2CID 152998021.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Nicolas I. (2022). "Pentecostals/Charismatics". In Ross, Kenneth R.; Bidegain, Ana M.; Johnson, Todd M. (eds.). Christianity in Latin America and the Caribbean. Edinburgh Companions to Global Christianity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 322–334. ISBN 9781474492164. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctv2mzb0p5.

- ^ a b Hanciles, Jehu J. (2008). Beyond Christendom: Globalization, African Migration, and the Transformation of the West. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-103-1. OCLC 221663356.

- ^ a b Freston, Paul (2008). "The Changing Face of Christian Proselytization: New Actors from the Global South". In Hackett, Rosalind I. J. (ed.). Proselytization Revisited: Rights Talk, Free Markets, and Culture Wars (1st ed.). New York and London: Routledge. pp. 109–138. ISBN 9781845532284. LCCN 2007046731.

- ^ a b Robbins, Joel (October 2004). Brenneis, Don; Strier, Karen B. (eds.). "The Globalization of Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33. Annual Reviews: 117–143. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093421. ISSN 1545-4290. JSTOR 25064848. S2CID 145722188.

- ^ McConnell, Francis John (1929). Human needs and world Christianity. New York: Friendship Press. OCLC 893126.

- ^ Van Dusen, Henry P. (1947). World Christianity: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow. New York: Abingdon-Cokesbury Press. OCLC 823535.

- ^ Robert, Dana L. "Historiographic Foundations". In Burrows, William R.; Gornik, Mark R.; McLean, Janice A. (eds.). Understanding World Christianity: The Vision and Work of Andrew F. Walls. Orbis Books. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-1-60833-021-8.

- ^ Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1938). Toward a world Christian fellowship. New York City: Association Press. OCLC 1149344.

- ^ Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1949). The Emergence of a World Christian Community. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. OCLC 396146.

- ^ a b c Phan, Peter C. (March 2013). "World Christianity: Its Implications for History, Religious Studies, and Theology". Horizons. 39 (2). Cambridge and New York City: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the College Theology Society, Villanova University: 171–188. doi:10.1017/S0360966900010665. ISSN 2050-8557. LCCN 77648693. OCLC 858609197. S2CID 170971032.

- ^ Walls, Andrew F. (1996). Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-106-2.

- ^ Lamin Sanneh (9 October 2003). Whose Religion Is Christianity?: The Gospel Beyond the West. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-8028-2164-5.

- ^ Hill, Graham Joseph (2016). Global Church: reshaping our conversations, renewing our mission, revitalizing our churches. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic. pp. 419–420. ISBN 978-0-8308-9903-6. OCLC 922799591.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (2007). The next Christendom: the coming of global Christianity (Rev. and expanded ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-19-518307-8. OCLC 71004136.

- ^ Burrows, William R.; Gornik, Mark R.; McLean, Janice A., eds. (2011). Understanding World Christianity: The Vision and Work of Andrew F. Walls. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

- ^ Akinade, Akintunde E., ed. (2010). A New Day: Essays on World Christianity in Honor of Lamin Sanneh. New York: Peter Lang.

- ^ "Professor Brian Stanley". School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ "Yale-Edinburgh Group". Yale Divinity Library. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ Hermann, Adrian; Burlacioiu, Ciprian (2016). "Introduction: Klaus Koschorke and the "Munich School" Perspective on the History of World Christianity". Journal of World Christianity. 6 (1): 4–27. doi:10.5325/jworlchri.6.1.0004. JSTOR 10.5325/jworlchri.6.1.0004.

- ^ Yong, Amos (2015). "Whither Evangelical Theology? The Work of Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen as a Case Study of Contemporary Trajectories". The Dialogical Spirit: Christian Reason and Theological Method in the Third Millennium. Cambridge: James Clark and Co. pp. 121–148. ISBN 9780227904350.

- ^ Phan, Peter C. (2008). "Doing Theology in World Christianity: Different Resources and New Methods". Journal of World Christianity. 1 (1): 27–53. doi:10.5325/jworlchri.1.1.0027. JSTOR 10.5325/jworlchri.1.1.0027.

- ^ Hill, Graham Joseph (2015). Global Church: Reshaping Our Conversations, Renewing Our Mission, Revitalizing Our Churches. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-4085-4.

- ^ Hill, Graham Joseph (2020). Salt, Light, and a City, Second Edition: Conformation—Ecclesiology for the Global Missional Community: Volume 2, Majority World Voices. Cascade Books. ISBN 9781532603259.

Further reading[edit]

- Asamoah-Gyadu, Kwabena; Chow, Alexander; Wild-Wood, Emma (March 2021). "Editorial: The COVID-19 Pandemic and World Christianity". Studies in World Christianity. 26 (3). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 213–218. doi:10.3366/swc.2020.0306. eISSN 1750-0230. ISSN 1354-9901.

- Cabrita, Joel; Maxwell, David; Wild-Wood, Emma, eds. (2017). Relocating World Christianity: Interdisciplinary Studies in Universal and Local Expressions of the Christian Faith. Theology and Mission in World Christianity. Vol. 7. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/9789004355026. ISBN 978-90-04-34262-0. ISSN 2452-2953.

- Frederiks, Martha; Nagy, Dorottya, eds. (2020). World Christianity: Methodological Considerations. Theology and Mission in World Christianity. Vol. 19. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/9789004444867. ISBN 978-90-04-44166-8. ISSN 2452-2953. S2CID 228894117.

- Hastings, Adrian, ed. (2000) [1999]. A World History of Christianity. Cambridge, U.K. and Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4875-8.

- Hunt, Stephen J., ed. (2015). Handbook of Global Contemporary Christianity: Themes and Developments in Culture, Politics, and Society. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 10. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/9789004291027. ISBN 978-90-04-26538-7. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Brenneman, Todd M. "Fundamentalist Christianity: From the American Margins to the Global Stage". In Hunt (2015), pp. 75–92.

- Ng, Peter Tze Ming. "Chinese Christianity: A ‘Global-Local’ Perspective". In Hunt (2015), pp. 152–166.

- Poon, Michael. "Christian Social Engagement in a Globalising Age". In Hunt (2015), pp. 247–265.

- Thorsen, Jakob Egeris. "Trends in Global Catholicism: The Refractions and Transformations of a World Church". In Hunt (2015), pp. 27–48.

- Wilkinson, Michael. "The Emergence, Development, and Pluralisation of Global Pentecostalism". In Hunt (2015), pp. 93–112.

- Jenkins, Philip (2011). The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0195146166.001.0001. ISBN 9780199767465. LCCN 2010046058. OCLC 678924439.

- Wilken, Robert Louis (2013). The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11884-1. JSTOR j.ctt32bd7m. LCCN 2012021755.

- Young, F. Lionel III (2021). World Christianity and the Unfinished Task: A Very Short Introduction. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books. ISBN 978-1-7252-6654-4