Politiques

Politiques ("políticos", en lengua francesa) fue la denominación que se dio durante las guerras de religión en Francia (a partir de 1568) a un grupo de intelectuales (muchos de ellos juristas), procedentes de la facción moderada de ambos bandos (hugonotes -protestantes- y católicos) que coincidían en la necesidad de restaurar la unidad política mediante una fuerte monarquía y el reconocimiento de algún tipo de tolerancia religiosa. Desde 1588 eran vistos como un grupo organizado, y presentados por sus adversarios (especialmente la Liga Católica) como herejes. Desde ese punto de vista, el término se utilizaba como peyorativo, identificándolo con el indiferentismo religioso y la ambigüedad moral.

Inicialmente eran presentados de forma conjunta con el grupo de los malcontents (los nobles que se oponían a la influencia de los Guisa y su relación con la Monarquía Hispánica de Felipe II).[1]

En su búsqueda de fundamentos firmes para la paz y seguridad en Francia, los politiques defendían la separación de los ámbitos religioso y lo político, así como la supremacía de la soberanía del rey sobre cualquier otra potestad interna o externa (particularismos locales y estamentales o poderes universales). Cierta relación guardan estos principios con la evolución posterior de la monarquía francesa hacia el absolutismo y la interpretación galicana de las relaciones Iglesia-Estado, que culminó a finales del siglo XVII con Luis XIV; aunque mucho más se identifican con el reinado de Enrique IV, el candidato protestante al trono que optó por convertirse al catolicismo para lograr el consenso más amplio (París bien vale una misa),[2] y promulgó el Edicto de Nantes que garantizaba a los hugonotes la libertad de culto en determinados lugares (1598, revocado precisamente por su nieto Luis XIV con el Edicto de Fontainebleau, 1685).[3]

Véase también

[editar]- Maquiavelo, maquiavelismo y razón de Estado

- Monarcómacos -Monarchomachs-

- Libertad religiosa, libertad de cultos y libertad de conciencia

- Michel de Montaigne (Essais, hasta 1592)[4]

- Pierre de L'Estoile (Diarios y Drolleries).

- François de Gravelle o François Gravelle (Politiques royales du François de Gravelle: dediées au tr. Ch. Roy de Fr. Henry IV, 1596)[5]

- Jean Bodin (Les six livres de la Republique, 1576 -edición latina de 1586-; Heptaplomeres -inédita hasta 1914-)[6]

- Renato Benoît o René Benoît (confesor de María Estuardo y traductor de la Biblia, fue elegido por Enrique IV para preparar su conversión al catolicismo)[7]

- Maximilien de Béthune, duque de Sully (Mémoires des sages et royales Œconomies d’Estat, domestiques, politiques et militaires de Henri le Grand, 1638)[8]

- Etienne Pasquier

- Philippe Duplessis-Mornay o Philippe de Mornay[9]

- Matteo Zampini, Matthieu Zampini o Mateo Zampini, jurista italiano que llegó a consejero de Enrique III y pasó al partido del Cardenal de Borbón (De la sucession du droict et prerogative du premiere prince de sang de France, 1588)[10]

- Pierre de Beloy o Pierre de Belloy (Apologie catholique contre les libelles, déclarations, advis et consultations faictes, escrites et publiées par les liguez perturbateurs du repos du royaume de France, 1585, De l'autorité du roi, 1587, Conférence des édicts de pacification des troubles esmeus au royaume de France, pour le faict de la religion, 1600)[11]

- Philippe Hurault de Cheverny[12]

- Michel de L'Hopital[13]

- Louis Le Roy[14]

[15]

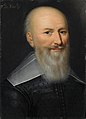

- Bodino.

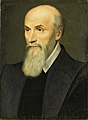

- Montaigne.

- Pasquier.

- Sully.

- L'Hopital.

- Hurault.

Notas

[editar]- ↑

- Francis de Crue, Le Parti des Politiques au lendemain de la Saint-Barthélemy. La Molle et Coconat, Paris, Librairie Plon, 1892, 368 p.

- Arlette Jouanna :

- « Un programme politique nobiliaire : les Mécontents et l'État (1574-1576) », in Philippe Contamine (éd.), L'État et les aristocraties (France, Angleterre, Écosse) XIIe-XVIIe siècle, Paris, Presses de l’ENS, 1989, pp. 247-278.

- Le devoir de révolte. La noblesse française et la gestation de l'État moderne, 1559-1661, Paris, Fayard, 1989.

- entrée Malcontents, in Arlette Jouanna, Jacqueline Boucher, Dominique Biloghi et Guy Le Thiec, Histoire et dictionnaire des guerres de Religion, Paris, Robert Laffont, collection « Bouquins », 1998, pp. 1068-1069.

- ↑ «1593-1594 Paris vaut bien une messe - [Musée national du château de Pau]». Archivado desde el original el 19 de enero de 2012.

- ↑ Murray N. Rothbard Radicalismo religioso y moderación absolutista en la Francia del siglo XVI Archivado el 23 de enero de 2012 en Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Biancamaria Fontana, Montaigne's Politics: Authority and Governance in the Essais

- ↑ William Farr Church, Constitutional thought in sixteenth-century France: a study in the evolution of ideas, pgs. 114 y 174.

- ↑ Bodino ha sido objeto de mil interpretaciones, a lo que ha contribuido haberse anticipado a su tiempo en la defensa atrevida de la tolerancia religiosa. (...) lejos de las posiciones disolventes de los monarcómacos, que proclamaban el derecho de resistencia, y de los maquiavelistas, que libraban a las actuaciones del poder de los límites racionales de la moralidad. (...) La soberanía necesitaba de la tolerancia religiosa para hacerse aceptable para todos los franceses, extenuados por las guerras de religión; la tolerancia necesitaba de la soberanía para hacerse respetar (...) Por esta razón (...) fue uno de los portavoces del denominado partido de los politiques, que entre católicos y hugonotes, entre los Guisa y los Borbones, intentaban la vía intermedia para llevar la paz definitiva a Francia.

Historia Tematica de Los Derechos Humanos, pg. 98.

Bodin never said that he was a “politique.” Briefly addressing the heart of the matter, historians have sought to make Bodin a convinced partisan of religious tolerance. During Bodin's lifetime however, religious tolerance, defined as civil tolerance and a legal admission of confessional diversity within a country or city, was not the ideal it would later become after the eighteenth century. In the sixteenth century, it was men like Sébastian Castellion who extolled the co-existence of many religions, with which the reformed camp disagreed. The struggle of the Huguenots from the beginning of the civil wars, was to convert the king and realm to the true religion. Tolerance was not an ideal since one cannot tolerate what one cannot possibly accept. For example how could one allow Christ to coexist with Belial, or a false religion to coexist with the one and only true religion? No further proof of this conviction is needed than the fierce struggle both Calvin and Beza waged against Castellion. This example causes one to ask the question: if Castellion supported freedom of religion, why did the leaders of the Reformation, who professed the same desire, denounce him so fervently? Because, in the reality, the French Reformers did not want freedom of religion which could have “opened the door to all manner of sects and heresies,” as Calvin said. At the beginning of the wars of religion, they wanted to obtain the recognition of the reformed religion as the sole religion in the realm. Yet, after thirty-six years of war, and after the conversion of Henry of Navarre, they understood that their project was too ambitious and had to be limited. Only through true religious tolerance could they convert the remainder of the kingdom at a later time. The unity of faith, and Calvinist religious concord were the ideal of Reformers too. Concerning the “politiques,” we only have descriptions of them from their adversaries who considered them atheists and heathens. For instance they were accused of having no religion because they were inclined to admit the definitive coexistence of different forms of worship in the interest of civil peace. Nevertheless, why have modern historians, placed men, who they considered the “most liberal and sympathetic,” such as Bodin, Etienne Pasquier, Duplessis-Mornay, Pierre de Beloy and many others in the party of the “politiques.” These historians have projected their modern ideals of tolerance, religious freedom, pluralism, and diversity on to the period of the Wars of Religion. Thus these scholars believed they had done a great service to the men of the past by presenting them as forerunners of the later values. But, as we have seen, Bodin viewed confessional concord as the means capable of returning religious, civil and political unity to the kingdom. It should be recalled however that the problem was not that of “liberty of conscience,” which the French government had already guaranteed by edicts in 1563, but the liberty to worship. The freedom to worship is also at the heart of the question of tolerance. When Bodin and many of his contemporaries thought about tolerance, it was only as provisional tolerance with the hope of achieving civil peace and religious reunification in the future. For Bodin, concord was essential since it formed the foundation of sovereignty and was necessary for the full exercise of power.(...)

The Maréchaux of France, the main officers of the crown, the second estate of the nobility all of the Huguenots, “politiques” and atheists and nearly all of the princes of the blood belonged to the party of the King of Navarre. Thus, In Bodin's view, the “politiques and atheists” were linked to the reformed, which he considered the enemy. - ↑ René Benoît

- ↑ Antonio Rivera, El legendario Gran Proyecto de Enrique IV y Sully.

- ↑

- Joachim Ambert, Duplessis Mornay, au, Études historique et politiques sur la situation de la France de 1549 à 1623. Genève : Slatkine reprints, 1970

- Hugues Daussy, Les huguenots et le roi : le combat politique de Philippe Duplessis-Mornay, 1572-1600. Genève: Librairie Droz, 2002

- J. A. Lalot, Essai historique sur la conférence tenue à Fontainebleau entre Duplessis-Mornay et Duperron le 4 mai 1600. Genève: Slatkine reprints, 1969

- ↑ Frédéric J. Baumgartner, Radical reactionaries: the political thought of the French Catholic League, pg. 252.

- ↑

- John William Allen Pierre de Belloy and the divine right en A history of political thought in the sixteenth century, pg. 383.

- Benjamin J. Kaplan, Divided by faith: religious conflict and the practice of toleration..., pg. 142.

- ↑ Dictionnaire Bouillet. Fuente citada en Philippe Hurault de Cheverny.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. Fuente citada en en:Michel de L'Hopital.

- ↑

- A. H. Becker, Un humaniste au XVIè siècle: Loys Le Roy, Paris 1896

- Enzo Sciacca, Umanesimo e scienza politica nella Francia del XVI secolo. Loys Le Roy, Olschki, Firenze 2007

- ↑

Max Horkheimer, Montaigne et la fonction du scepticisme, citado por Timothy J. Reiss, The meaning of literature, pg. 54.The tendency to remain neutral in religious questions and to subordinate religion to reasons of state, the recourse to a strong state which would be the guarantor of the security of commerce and exchange, corresponds to the conditions of existence of the parvenue bourgeoisie and its alliance with absolute monarchie.

Enlaces externos

[editar]- French Political Pamphlets Collection at the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

- Politiques ou malcontents en Dictionnaire de l'Histoire de France, Larrouse.

- [http://dep-histoire-art.univ-pau.fr/live/digitalAssets/88/88278_Hist._Moderne_Bidouze.pdf (enlace roto disponible en Internet Archive; véase el historial, la primera versión y la última). Les affrontements religieux en France du début du XVIe siècle au milieu du XVIIe siècle]