Triphenylphosphan

Van Wikipedia, de gratis encyclopedie

Van Wikipedia, de gratis encyclopedie

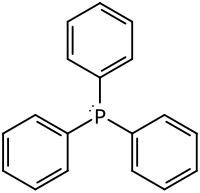

| Strukturformel | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Allgemeines | |||||||||||||||||||

| Name | Triphenylphosphan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Andere Namen | |||||||||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C18H15P | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kurzbeschreibung | farblose, monokline Prismen[2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Externe Identifikatoren/Datenbanken | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Eigenschaften | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 262,28 g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aggregatzustand | fest[2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dichte | |||||||||||||||||||

| Schmelzpunkt | |||||||||||||||||||

| Siedepunkt | |||||||||||||||||||

| Löslichkeit | |||||||||||||||||||

| Brechungsindex | 1,6358 (80 °C)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sicherheitshinweise | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| MAK | DFG/Schweiz: 5 mg·m−3 (gemessen als einatembarer Staub)[3][5] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Toxikologische Daten | |||||||||||||||||||

| Soweit möglich und gebräuchlich, werden SI-Einheiten verwendet. Wenn nicht anders vermerkt, gelten die angegebenen Daten bei Standardbedingungen (0 °C, 1000 hPa). Brechungsindex: Na-D-Linie, 20 °C | |||||||||||||||||||

Triphenylphosphan (auch: Triphenylphosphin, Triphenylphosphor, Phosphortriphenyl) ist ein Ligand für die Herstellung von Metallkomplexen, die in der chemischen Synthese benötigt werden, und ist auch selbst ein Reagenz in diversen Reaktionen. Es gehört zur Gruppe der Triphenylverbindungen in der Stickstoffgruppe des Periodensystems mit den weiteren Vertretern Triphenylamin, Triphenylarsin, Triphenylstibin und Triphenylbismutin.

Herstellung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Im Labormaßstab kann Triphenylphosphan durch Einwirkung von Phenylmagnesiumbromid auf Phosphortrichlorid dargestellt werden.[7] Industriell erfolgt die Herstellung aus Phosphortrichlorid, Chlorbenzol und Natrium.[8]

Eigenschaften

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Triphenylphosphin kristallisiert im monoklinen Kristallsystem in der Raumgruppe P21/a (Raumgruppen-Nr. 14, Stellung 3) mit den Gitterparametern a = 11,329 Å; b = 14,915 Å, c = 8,440 Å und β = 92,12 ° sowie vier Formeleinheiten pro Elementarzelle.[9] Auch eine trikline Modifikation ist bekannt.[10] Triphenylphosphin, das aus bestimmten Lösungsmitteln (z. B. Aceton) kristallisiert wird, weist Tribolumineszenz auf.[11]

- Stäbchenmodell des Triphenylphosphans.

- Kalottenmodell des Triphenylphosphans.

Reaktionen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Triphenylphosphin ist eine schwache Base[12] und lässt sich vergleichsweise leicht oxidieren. An der Luft bildet sich mit der Zeit Triphenylphosphanoxid, allerdings ist die Verbindung deutlich weniger oxidationsempfindlich als Alkylphosphane.[13]

Die Oxidierbarkeit macht man sich auch synthetisch zunutzer, da Triphenylphosphin diverse Substrate reduzieren kann, wobei es selbst ebenfalls zum Triphenylphosphinoxid oxidiert wird. Bei der Staudinger-Reduktion wird ein Azid zum primären Amin reduziert, wobei elementarer Stickstoff freigesetzt wird.[14] Aliphatische N-Oxide können leicht durch Triphenylphosphin reduziert werden, aromatische wie Pyridin-N-oxid erfordern oft höhere Temperaturen.[15] Eine Methode zur Reduktion aromatischer N-Oxide unter Lichteinfluss wurde ebenfalls beschrieben.[16] Triphenylphosphin reduziert außerdem Peroxide, wobei Hydroperoxide deutlich schneller reagieren als andere.[17] Beispielsweise wurden die Reduktionen von Ascaridol und tert-Butylhydroperoxid beschrieben.[18][19] Die Reaktion eignet sich auch zur spektrophotometrischen Bestimmung von Peroxiden.[17] Daneben wird Triphenylphosphin auch zur reduktiven Aufarbeitung bei Ozonolysen verwendet.[20][21]

Herstellung von Phosphoniumsalzen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Triphenylphosphin eignet sich zur Synthese von Alkyltriphenylphosphoniumsalzen aus Alkylhalogeniden (Alkylchloriden, -bromiden, -iodiden) und ähnlichen Verbindungen (Mesylaten, Tosylaten, Triflaten). Diese sind wiederum Vorläufer für Ylide für Wittig-Reaktionen.[22][23]

Appel-Reaktion

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Bei der Appel-Reaktion wird ein Alkohol durch Umsetzung mit Triphenylphosphin und Tetrachlorkohlenstoff oder Tetrabromkohlenstoff zu einem Alkylchlorid oder Alkylbromid umgesetzt.[24][25]

Mitsunobu-Reaktion

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Bei der Mitsunobu-Reaktion wird ein Alkohol mit Diethylazodicarboxylat, Triphenylphosphin und einem Nucleophil umgesetzt, wobei die Hydroxylgruppe unter Stereoinversion substituiert wird. Dadurch können zum Beispiel Ester gebildet werden (bei intramolekularer Reaktion Lactone). Eine wichtige Anwendung ist auch die Inversion der Stereokonfiguration chiraler sekundärer Alkohole durch Veresterung und Hydrolyse. Außerdem können Ether, Azide, Nucleoside und andere Stoffgruppen erzeugt werden. Da das Nucleophil eine ausreichende Acidität aufweisen muss, sind C-Nucleophile die Ausnahme.[26]

Corey-Fuchs-Reaktion

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Bei der Corey-Fuchs-Reaktion werden Carbonyle in Alkine überführt, indem diese mit Triphenylphosphin und Tetrabromkohlenstoff umgesetzt werden.[27][28]

Metallkomplexe

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Triphenylphosphin bildet eine große Zahl an Übergangsmetallkomplexen. Der Ligandenkegelwinkel beträgt etwa 145°.[29] Wichtige Katalysatoren sind beispielsweise Bis(triphenylphosphin)palladium(II)-chlorid und Tetrakis(triphenylphosphin)palladium(0), die aus Triphenylphosphin hergestellt und beispielsweise für Kreuzkupplungen eingesetzt werden.[30][31] Es ist auch ein Ligand im Wilkinson-Katalysator ([RhCl(PPh3)3]),[32][33] sowie in weiteren Rhodium-Komplexen, die beispielsweise zur Hydroformylierung eingesetzt werden.[34] Weitere Komplexe, die Triphenylphosphinliganden tregen sind Vaskas Komplex[35] und das Stryker-Reagenz.[36]

Von Nickel sind beispielsweise die Komplexe Bis(triphenylphosphin)nickel(II)-chlorid und Bis(triphenylphosphin)nickel(II)-bromid bekannt,[37] von Platin Tris(triphenylphosphin)platin(0) und Tetrakis(triphenylphosphin)platin(0).[38] Auch von Silberchlorid und Gold(I)-chlorid bilden Triphenylphosphinkomplexe.[39][40] Darüber hinaus sind diverse weitere Komplexe von Rhodium, Ruthenium, Iridium und Osmium bekannt.[41]

- Tetrakis(triphenylphosphin)palladium(0)

- Wilkinson-Katalysator

- Vaskas Komplex

- Stryker-Reagenz

Verwendung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Triphenylphosphin selbst ist ein wichtiges Reagenz in der organischen Synthese (siehe Abschnitt Reaktionen). Außerdem wird es als Ligand zur Herstellung vieler Komplexe benötigt, die zum Teil ebenfalls relevante synthetische Anwendungen haben (siehe Abschnitt Metallkomplexe).

Neben der direkten Verwendung in der organischen Synthese und der Verwendung als Ligand in der Synthese von Komplexen, dient es auch als Edukt für die Synthese weiterer Reagenzien, zum Beispiel TPPTS,[42] Diphenylketen,[43] Chiraphos,[44] sowie durch Reduktion mit Lithium Lithiumdiphenylphosphid.[45]

Verwandte Verbindungen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Andere Arylphosphin-Liganden sind beispielsweise Josiphos,[46] BINAP[47] und SegPhos.[48] Triphenylphosphin existiert auch in polymerfixierter Form, die aus Polystyrol und Diphenylphosphinchlorid hergestellt wird.[49]

Einzelnachweise

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ Eintrag zu TRIPHENYLPHOSPHINE in der CosIng-Datenbank der EU-Kommission, abgerufen am 16. Februar 2020.

- ↑ a b c d Eintrag zu Triphenylphosphan. In: Römpp Online. Georg Thieme Verlag, abgerufen am 3. Mai 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e Eintrag zu Triphenylphosphin in der GESTIS-Stoffdatenbank des IFA, abgerufen am 3. Januar 2023. (JavaScript erforderlich)

- ↑ a b David R. Lide (Hrsg.): CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 90. Auflage. (Internet-Version: 2010), CRC Press / Taylor and Francis, Boca Raton FL, Physical Constants of Organic Compounds, S. 3-512.

- ↑ Schweizerische Unfallversicherungsanstalt (Suva): Grenzwerte – Aktuelle MAK- und BAT-Werte (Suche nach 603-35-0 bzw. Triphenylphosphan), abgerufen am 2. November 2015.

- ↑ United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pesticides and Toxic Substances. 8EHQ-0384-0014.

- ↑ J. Dodonow, H. Medox: Zur Kenntnis der Grignardschen Reaktion: Über die Darstellung von Tetraphenyl-phosphoniumsalzen. In: Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. Band 61, Nr. 5, 1928, S. 907 – 911, doi:10.1002/cber.19280610505.

- ↑ D. E. C. Corbridge: Phosphorus: An Outline of its Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Technology. 5. Auflage. Elsevier, Amsterdam 1995, ISBN 0-444-89307-5.

- ↑ B. J. Dunne, A. G. Orpen: Triphenylphosphine: a redetermination. In: Acta Crystallographica Section C Crystal Structure Communications. Band 47, Nr. 2, 15. Februar 1991, S. 345–347, doi:10.1107/S010827019000508X.

- ↑ H. Kooijman, A. L. Spek, K. J. C. van Bommel, W. Verboom, D. N. Reinhoudt: A Triclinic Modification of Triphenylphosphine. In: Acta Crystallographica Section C Crystal Structure Communications. Band 54, Nr. 11, 15. November 1998, S. 1695–1698, doi:10.1107/S0108270198009305.

- ↑ Martin B. Hocking, Francies W. VandervoortMaarschalk, John McKiernan, Jeffrey I. Zink: Acetone-induced triboluminescence of triphenylphosphine. In: Journal of Luminescence. Band 51, Nr. 6, Mai 1992, S. 323–334, doi:10.1016/0022-2313(92)90061-D.

- ↑ Wm. A. Henderson, C. A. Streuli: The Basicity of Phosphines. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society. Band 82, Nr. 22, November 1960, S. 5791–5794, doi:10.1021/ja01507a008.

- ↑ Jeff E. Cobb, Cynthia M. Cribbs, Brad R. Henke, David E. Uehling, Alejandro G. Hernan, Colin Martin, Christopher M. Rayner: Triphenylphosphine. In: Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK 2005, ISBN 978-0-471-93623-7, doi:10.1002/047084289x.rt366.pub2.

- ↑ Shu Liu, Kevin J. Edgar: Staudinger Reactions for Selective Functionalization of Polysaccharides: A Review. In: Biomacromolecules. Band 16, Nr. 9, 14. September 2015, S. 2556–2571, doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00855.

- ↑ Edgar Howard, William F. Olszewski: The Reaction of Triphenylphosphine with Some Aromatic Amine Oxides 1. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society. Band 81, Nr. 6, März 1959, S. 1483–1484, doi:10.1021/ja01515a050.

- ↑ Chikara Kaneko, Masami Yamamori, Atsushi Yamamoto, Reiko Hayashi: Irradiation of aromatic amine oxides in dichloromethane in presence of triphenylphosphine: A facile deoxygenation procedure of aromatic amine N-oxides. In: Tetrahedron Letters. Band 19, Nr. 31, Januar 1978, S. 2799–2802, doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)94866-X.

- ↑ a b R. A. Stein, Vida. Slawson: Spectrophotometric Hydroperoxide Determination by the Use of Triphenylphosphine. In: Analytical Chemistry. Band 35, Nr. 8, 1. Juli 1963, S. 1008–1010, doi:10.1021/ac60201a027.

- ↑ Gary O. Pierson, Olaf A. Runquist: Reduction of ascaridole with triphenylphosphine. In: The Journal of Organic Chemistry. Band 34, Nr. 11, November 1969, S. 3654–3655, doi:10.1021/jo01263a105.

- ↑ R. Hiatt, R. J. Smythe, Christine McColeman: The Reaction of Hydroperoxides with Triphenylphosphine. In: Canadian Journal of Chemistry. Band 49, Nr. 10, 15. Mai 1971, S. 1707–1711, doi:10.1139/v71-277.

- ↑ Patrizia Ferraboschi, Claudio Gambero, Morteza Nasr Azadani, Enzo Santaniello: Reduction of Ozonides by Means of Polymeric Triphenylphosphine: Simplified Synthesis of Carbonyl Compounds from Alkenes. In: Synthetic Communications. Band 16, Nr. 6, Mai 1986, S. 667–672, doi:10.1080/00397918608057738.

- ↑ Otto Lorenz, Carl R. Parks: Ozonides from Asymmetrical Olefins. Reaction with Triphenylphosphine. In: The Journal of Organic Chemistry. Band 30, Nr. 6, Juni 1965, S. 1976–1981, doi:10.1021/jo01017a064.

- ↑ Organophosphorus chemistry: from molecules to applications. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2019, ISBN 978-3-527-67225-7.

- ↑ S. Trippett: The Wittig reaction. In: Quarterly Reviews, Chemical Society. Band 17, Nr. 4, 1963, S. 406, doi:10.1039/qr9631700406.

- ↑ Rolf Appel: Tertiary Phosphane/Tetrachloromethane, a Versatile Reagent for Chlorination, Dehydration, and P?N Linkage. In: Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. Band 14, Nr. 12, Dezember 1975, S. 801–811, doi:10.1002/anie.197508011.

- ↑ Andrew Jordan, Ross M. Denton, Helen F. Sneddon: Development of a More Sustainable Appel Reaction. In: ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. Band 8, Nr. 5, 10. Februar 2020, S. 2300–2309, doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07069.

- ↑ David L. Hughes: PROGRESS IN THE MITSUNOBU REACTION. A REVIEW. In: Organic Preparations and Procedures International. Band 28, Nr. 2, April 1996, S. 127–164, doi:10.1080/00304949609356516.

- ↑ Damien Habrant, Vesa Rauhala, Ari M. P. Koskinen: Conversion of carbonyl compounds to alkynes: general overview and recent developments. In: Chemical Society Reviews. Band 39, Nr. 6, 2010, S. 2007, doi:10.1039/b915418c.

- ↑ E.J. Corey, P.L. Fuchs: A synthetic method for formyl→ethynyl conversion (RCHO→RC≡CH or RC≡CR′). In: Tetrahedron Letters. Band 13, Nr. 36, 1972, S. 3769–3772, doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)94157-7.

- ↑ Thomas E. Müller, D. Michael P. Mingos: Determination of the Tolman cone angle from crystallographic parameters and a statistical analysis using the crystallographic data base. In: Transition Metal Chemistry. Band 20, Nr. 6, Dezember 1995, S. 533–539, doi:10.1007/BF00136415.

- ↑ Marcella Ioele, Giancarlo Ortaggi, Marco Scarsella, Giancarlo Sleiter: A rapid and convenient synthesis of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(O) and -platinum(O) complexes by phase-transfer catalysis. In: Polyhedron. Band 10, Nr. 20-21, Januar 1991, S. 2475–2476, doi:10.1016/S0277-5387(00)86211-7.

- ↑ PALLADIUM-CATALYZED REACTION OF 1-ALKENYLBORONATES WITH VINYLIC HALIDES: (1Z,3E)-1-PHENYL-1,3-OCTADIENE. In: Organic Syntheses. Band 68, 1990, S. 130, doi:10.15227/orgsyn.068.0130.

- ↑ Jeremy M. Praetorius, Cathleen M. Crudden: N-Heterocyclic carbene complexes of rhodium: structure, stability and reactivity. In: Dalton Transactions. Nr. 31, 2008, S. 4079, doi:10.1039/b802114g.

- ↑ J. A. Osborn, F. H. Jardine, J. F. Young, G. Wilkinson: The preparation and properties of tris(triphenylphosphine)halogenorhodium(I) and some reactions thereof including catalytic homogeneous hydrogenation of olefins and acetylenes and their derivatives. In: Journal of the Chemical Society A: Inorganic, Physical, Theoretical. 1966, S. 1711, doi:10.1039/j19660001711.

- ↑ Cunyao Li, Wenlong Wang, Li Yan, Yunjie Ding: A mini review on strategies for heterogenization of rhodium-based hydroformylation catalysts. In: Frontiers of Chemical Science and Engineering. Band 12, Nr. 1, März 2018, S. 113–123, doi:10.1007/s11705-017-1672-9.

- ↑ Jay A. Labinger: Tutorial on Oxidative Addition. In: Organometallics. Band 34, Nr. 20, 26. Oktober 2015, S. 4784–4795, doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00565.

- ↑ Carl Deutsch, Norbert Krause, Bruce H. Lipshutz: CuH-Catalyzed Reactions. In: Chemical Reviews. Band 108, Nr. 8, 1. August 2008, S. 2916–2927, doi:10.1021/cr0684321.

- ↑ L. M. Venanzi: 140. Tetrahedral nickel(II) complexes and the factors determining their formation. Part I. Bistriphenylphosphine nickel(II) compounds. In: Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed). 1958, S. 719, doi:10.1039/jr9580000719.

- ↑ Lamberto Malatesta, Renato Ugo: 385. Triphenylphosphine derivatives of platinum(0). In: Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed). 1963, S. 2080, doi:10.1039/jr9630002080.

- ↑ N. C. Baenziger, W. E. Bennett, D. M. Soborofe: Chloro(triphenylphosphine)gold(I). In: Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry. Band 32, Nr. 3, 1. März 1976, S. 962–963, doi:10.1107/S0567740876004330.

- ↑ A. Cassel: Chlorotris(triphenylphosphine)silver. In: Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry. Band 37, Nr. 1, 15. Januar 1981, S. 229–231, doi:10.1107/S0567740881002598.

- ↑ J. J. Levison, S. D. Robinson: Transition-metal complexes containing phosphorus ligands. Part III. Convenient syntheses of some triphenylphosphine complexes of the platinum metals. In: Journal of the Chemical Society A: Inorganic, Physical, Theoretical. 1970, S. 2947, doi:10.1039/j19700002947.

- ↑ Sven Hida, Paul J. Roman, Allen A. Bowden, Jim D. Atwood: Synthesis of tri( m ‐sulfonatedphenyl)phosphine (tppts): The importance of ph in the work‐up. In: Journal of Coordination Chemistry. Band 43, Nr. 4, April 1998, S. 345–348, doi:10.1080/00958979808230447.

- ↑ S. D. Darling, R. L. Kidwell: Diphenylketene. Triphenylphosphine dehalogenation of α-bromodiphenylacetyl bromide. In: The Journal of Organic Chemistry. Band 33, Nr. 10, Oktober 1968, S. 3974–3975, doi:10.1021/jo01274a074.

- ↑ M. D. Fryzuk, B. Bosnich: Asymmetric synthesis. Production of optically active amino acids by catalytic hydrogenation. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society. Band 99, Nr. 19, September 1977, S. 6262–6267, doi:10.1021/ja00461a014.

- ↑ A. M. Aguiar, J. Beisler, A. Mills: Lithium Diphenylphosphide: A Convenient Source and Some Reactions. In: The Journal of Organic Chemistry. Band 27, Nr. 3, März 1962, S. 1001–1005, doi:10.1021/jo01050a076.

- ↑ Hans Ulrich Blaser, Benoît Pugin, Felix Spindler: Having Fun (and Commercial Success) with Josiphos and Related Chiral Ferrocene Based Ligands. In: Helvetica Chimica Acta. Band 104, Nr. 1, Januar 2021, doi:10.1002/hlca.202000192.

- ↑ Ryoji Noyori, Hidemasa Takaya: BINAP: an efficient chiral element for asymmetric catalysis. In: Accounts of Chemical Research. Band 23, Nr. 10, 1. Oktober 1990, S. 345–350, doi:10.1021/ar00178a005.

- ↑ Jianzhong Chen, Nicholas A. Butt, Wanbin Zhang: The application of the chiral ligand DTBM-SegPHOS in asymmetric hydrogenation. In: Research on Chemical Intermediates. Band 45, Nr. 12, Dezember 2019, S. 5959–5974, doi:10.1007/s11164-019-04013-w.

- ↑ Ziad Moussa, Zaher M. A. Judeh, Saleh A. Ahmed: Polymer-supported triphenylphosphine: application in organic synthesis and organometallic reactions. In: RSC Advances. Band 9, Nr. 60, 2019, S. 35217–35272, doi:10.1039/C9RA07094J, PMID 35530694, PMC 9074440 (freier Volltext).