Chilean Civil War of 1891

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2022) |

| Chilean Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

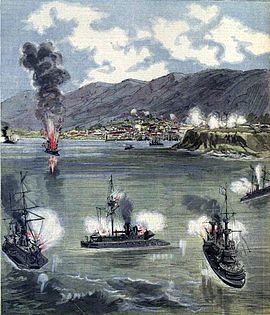

Picture of the rebel fleet attacking Valparaíso, late August 1891, published in Le Petit Journal. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| José Manuel Balmaceda † Orozimbo Barbosa † José Miguel Alcérreca † José Velásquez Bórquez Eulogio Robles Pinochet † | Jorge Montt Adolfo Holley Estanislao del Canto Emil Körner | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000 2 torpedo boats | ~10,000 1 monitor 1 armoured frigate 1 cruiser 1 corvette 1 battery ship (January 1891) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 armoured frigate | |||||||

| 5,000[1] | |||||||

The Chilean Civil War of 1891 (also known as Revolution of 1891) was a civil war in Chile fought between forces supporting Congress and forces supporting the President, José Manuel Balmaceda from 16 January 1891 to 18 September 1891. The war saw a confrontation between the Chilean Army and the Chilean Navy, siding with the president and the congress, respectively. This conflict ended with the defeat of the Chilean Army and the presidential forces, and with President Balmaceda committing suicide as a consequence of the defeat.[2] In Chilean historiography the war marks the end of the Liberal Republic and the beginning of the Parliamentary Era.

Causes

[edit]

The Chilean Civil War grew out of political disagreements between the president of Chile, José Manuel Balmaceda, and the Chilean congress. In 1889, the congress became distinctly hostile to the administration of Balmaceda, and the political situation became serious, at times threatening to involve the country in civil war. According to usage and custom in Chile at the time, a minister could not remain in office unless supported by a majority in both houses of the congress. Balmaceda found himself in the difficult position of being unable to appoint any ministers that could control a majority in the senate and chamber of deputies, and at the same time act in accordance with his own views of the administration of public affairs. At this juncture, the president assumed that the constitution gave him the power of nominating and maintaining in office any ministers of his choice and that congress had no power to interfere.

The Congress was now only waiting for a suitable opportunity to assert its authority. In 1890, it came to light that President Balmaceda had decided to nominate a close personal friend as his successor. This brought matters to confrontation and the congress refused to approve a budget for supplies to run the government. Balmaceda compromised with congress, agreeing to nominate a cabinet to their liking on condition that the budget would be approved. This cabinet, however, resigned when the ministers understood the full scope of the conflict between the president and congress. Balmaceda then nominated a cabinet not in accord with the views of Congress under Claudio Vicuña, whom it was no secret Balmaceda intended to be his successor. To avoid opposition to his actions, Balmaceda refrained from summoning an extraordinary session of the legislature for the discussion of the estimates of revenue and expenditure for 1891.

Crisis

[edit]On 1 January 1891, president Balmaceda published a Manifest to the Nation in various newspapers to the effect that the budget of 1890 would be considered the official budget for 1891. This act was interpreted by the opposition as illegal and beyond the attributes of the executive power. As protest against the action of President Balmaceda, the vice-president of the senate, Waldo Silva, and the president of the chamber of deputies, Ramón Barros Luco, issued a proclamation appointing Captain Jorge Montt commander of the navy, and stating that the navy could not recognize the authority of Balmaceda so long as he did not administer public affairs in accordance with the constitutional law of Chile. The majority of the members of congress sided with this movement, and signed an Act of Deposition of President Balmaceda

Rebellion of the navy

[edit]| History of Chile |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Years in Chile |

On 6 January 1891, the political leaders of the Congressional party embarked on board the armored frigate Blanco Encalada, at Valparaíso, and Captain Jorge Montt of that vessel hoisted a broad pennant as commodore of the Congressional fleet. On 7 January the Blanco Encalada, accompanied by the Esmeralda and O'Higgins and other vessels, sailed out of Valparaiso harbour and proceeded northwards to Tarapacá to organize armed resistance against the president.

For the present, and without prejudice to the future, command of the sea was held by Montt's squadron (January). The rank and file of the army remained faithful to the executive, and thus in the early part of the war the Gobiernistas, speaking broadly, possessed an army without a fleet, the congress a fleet without an army. Balmaceda hoped to create a navy; the congress took steps to recruit an army by taking its sympathizers on board the fleet.

Immediately on the outbreak of the revolution President Balmaceda published a decree declaring Montt and his companions to be traitors, and without delay organized an army of some 40,000 men for the suppression of the insurrectionary movement. While both sides were preparing for hostilities, Balmaceda administered the government under dictatorial powers with a congress of his own nomination. In June 1891 he ordered the presidential election to be held, and Claudio Vicuña was duly declared chosen as president of the republic for the term commencing in September 1891.

Preparations had long been made for the naval insurrection, and in the end few vessels of the Chilean navy adhered to the cause of Balmaceda. But amongst these were two new and fast torpedo gunboats, Almirante Condell and Almirante Lynch, and in European dockyards (incomplete) lay the most powerful vessel of the navy, the battleship Capitán Prat, and two fast cruisers. If these were secured by the Balmacedists the naval supremacy of the congress would be seriously challenged. The resources of Balmaceda were running short on account of the heavy military expenses, and he determined to dispose of the reserve of silver bullion accumulated in the vaults of the Casa de Moneda in accordance with the terms of the law for the conversion of the note issue. The silver was conveyed abroad in a British man-of-war, and disposed of partly for the purchase of a fast steamer to be fitted as an auxiliary cruiser and partly in payment for other kinds of war material.

Itata incident

[edit]The organization of the revolutionary forces went on slowly. They were experiencing difficulty in obtaining the necessary arms and ammunition. A supply of rifles was bought in the United States, and embarked on board the Itata, a Chilean vessel in the service of the rebels. The United States authorities refused to allow this steamer to leave San Diego, and a guard was stationed on the ship. The Itata, however, slipped away and made for the Chilean coast, carrying with her the representatives of the United States. A fast cruiser was immediately sent in pursuit, but only succeeded in overtaking the rebel ship after she was at her destination. The Itata was then forced to return to San Diego without landing her cargo for the insurgents.

Hostilities

[edit]The first shot was fired, on 16 January, by the Blanco at the Valparaiso batteries, and landing parties from the warships engaged small parties of government troops at various places during January and February. Balmaceda's principal forces were stationed in and about Iquique, Coquimbo, Valparaíso, Santiago and Concepción. The troops at Iquique and Coquimbo were necessarily isolated from the rest and from each other, and military operations began, as in the campaign of 1879 in this quarter, with a naval descent upon Pisagua followed by an advance inland to Dolores.

The Congressional forces failed at first to make good their footing (16–23 January), but, though defeated in two or three actions, they brought off many recruits and a quantity of munitions of war. On 26 January they retook Pisagua, and on the 15 February the Balmacedist commander, Eulogio Robles, who offered battle in the expectation of receiving reinforcements from Tacna, was completely defeated on the old battlefield of San Francisco. Robles fell back along the railway, called up troops from Iquique, and beat the invaders at Huara on 17 February, but Iquique in the meanwhile fell to the Congressional fleet on 16 February.

Battle of Pozo Almonte

[edit]

The Pisagua line of operations was at once abandoned, and the military forces of the congress were moved by sea to Iquique, whence, under the command of Colonel Estanislao del Canto, they started inland. The battle of Pozo Almonte, fought on 7 March, was desperately contested, but Del Canto was superior in numbers, and Robles was himself wounded and then executed inside a field hospital and his army dispersed. After this the other Balmacedist troops in the north gave up the struggle. The garrison of Tacna (at that time part of Chile) was driven into Peru, others joined the Congressional Army and the rest made a laborious retreat from Calama to Santiago, in the course of which it twice crossed the main chain of the Andes. These forces were later sent to Coquimbo to form the fifth division of the Presidential Army.

Sinking of the Blanco Encalada

[edit]Early in April a portion of the revolutionary squadron, comprising the armoured frigate Blanco Encalada and other ships, was sent southward for reconnoitring purposes and put into the port of Caldera. During the night of 23 April, and whilst the Blanco Encalada was lying quietly at anchor in Caldera Bay, the Almirante Lynch torpedo gunboat, belonging to the Balmaceda faction, steamed into the bay of Caldera and discharged a torpedo at the rebel ship. The Blanco Encalada sank in a few minutes and 300 of her crew perished. This coup severely weakened the Congressional squadron.

Congressional offensive

[edit]

The Revolutionary Junta, created on 13 April, now firmly established in Iquique prosecuted the war vigorously, and by the end of April the whole area was in the hands of the "rebels" from the Peruvian border to the outposts of the Balmacedists at Coquimbo and La Serena. The Junta now began the formation of a properly organized army for the next campaign, which, it was believed universally on both sides, would be directed against Coquimbo. The necessary arms and ammunition were arranged for in Europe; they were shipped in a British vessel, and transferred to a Chilean steamer at Fortune Bay, in Tierra del Fuego, close to the Straits of Magellan and the Falkland Islands, and thence carried to Iquique, where they were safely disembarked early in July 1891. A force of 20,000 men was now raised by the junta, but with weapons and ammunition for only 9,000, and preparations were rapidly pushed forward for a move to the south with the object of attacking Valparaiso and Santiago, because in a few months the arrival of the new ships from Europe would reopen the struggle for command of the sea so the Congressional party could no longer aim at a methodical conquest of successive provinces, but was compelled to attempt to crush the Presidentialist forces at a blow.

Where this blow was to fall was not decided up to the last moment, but the instrument which was to deliver it was prepared with all the care possible under the circumstances. Del Canto was made commander-in-chief, and an ex-Prussian officer, Emil Körner, chief of staff. The army was organized in three brigades of all arms, at Iquique, Caldera and Vallenar. Körner superintended the training of the men, gave instruction in tactics to the officers, caused maps to be prepared, and in general took every precaution that his experience could suggest to ensure success. Del Canto was himself no mere figurehead, but a thoroughly capable leader who had distinguished himself at Tacna (1880) and Miraflores (1881), as well as in the present war. The men were enthusiastic, and the officers unusually numerous. The artillery was fair, the cavalry good, and the train and auxiliary services well organized. About one-third of the infantry were armed with the Austrian Mannlicher magazine rifle, which now made its first appearance in war, the remainder had the French Gras and other breech-loaders, which were also the armament of the Presdidential infantry. Balmaceda could only wait upon events, but he prepared his forces as best he was able, and his torpedo gunboats constantly harried the Congressional navy. By the end of July Del Canto and Körner had done their work as well as time permitted, and early in August the troops prepared to embark, not for Coquimbo, but for Valparaiso itself.

Lo Cañas massacre

[edit]At the beginning of August the disembarking of the Congressional Army was expected, and both sides were preparing for the coming battles. The Presidential Army had four divisions; Santiago, Valparaiso, Concepcion and Coquimbo, and President Balmaceda had ordered his generals to not engage the enemy unless they had a combined force of al least 14,000 men. But these four division were scattered across the country, with only the Santiago and Valparaiso divisions near each other, the Concepcion division was 311 miles from the Capital and the Coquimbo division 287 miles. As the Junta had only 9,000 men ready for battle they took precautions to prevent the Presidential Army from concentrating its forces.

On 16 August the Revolutionary Committee of Santiago received instructions from the Junta to perform sabotage operations, destroying railroads, bridges and the telegraph. Two days later, a group of 84 young men met at the Lo Cañas Estate, property of Carlos Walker Martinez, a former Senator, member of the Revolutionary Committee and brother of Joaquin Walker Martinez, a member of the Junta. This group was armed with rifles and dynamite to destroy a bridge over the Maipo River to prevent the Concepcion Division from advancing north. They were discovered by a patrol and ambushed by a force of 90 cavalry and 40 infantry men. Few of the revolutionaries died in the ambush, the rest either surrendered, expecting to be taken as POW's, or tried to escape but were capture by the cavalry. Commander Alejo San Martin ordered his men to torture and interrogate the prisoners and later he organized a court martial and decided to execute all of the men his troops had captured, later he burned the bodies. This massacre had an important effect on the Chilean people, gaining more support for the Junta and making so that those loyal to the President started to waver on their convictions.

Battle of Concón

[edit]

In the middle of August 1891 the rebel forces were embarked at Iquique, numbering in all about 9,000 men, and sailed for the south. The expedition by sea was admirably managed, and on 10 August the Congressional army was disembarked at Quintero, about 20 km. north of Valparaiso and not many miles out of range of its batteries, and marched to Concón, where the Balmacedists were entrenched.

Balmaceda was surprised, but acted promptly. The first battle was fought on the Aconcagua river at Concón on the 21st. The eager infantry of the Congressional army forced the passage of the river and stormed the heights held by the Gobiernistas. A severe fight ensued, in which the troops of President Balmaceda were defeated with heavy loss. The killed and wounded of the Balmacedists numbered 1,600, and nearly all the prisoners, about 1,500 men, enrolled themselves in the rebel army, which thus more than made good its loss of 1,000 killed and wounded.

Battle of La Placilla

[edit]

After the victory at Concón the insurgent army, under command of General Campos, pressed on towards Valparaiso, but were soon brought up by the strong fortified position of the Balmacedist general Orozimbo Barbosa at Viña del Mar, whither Balmaceda hurried up all available troops from Valparaiso and Santiago, and even from Concepcion. Del Canto and Körner now resolved on a daring step. Supplies of all kinds were brought up from Quintero to the front, and on 24 August the army abandoned its line of communications and marched inland. The flank march was conducted with great skill, little opposition was encountered, and the rebels finally appeared to the southeast of Valparaiso.

There, on 28 August, the final struggle in the conflict took place: the decisive battle of La Placilla. Concon had been perhaps little more than the destruction of an isolated corps; the second battle was a fair trial of strength, for Balmaceda's generals Barbosa and Alcerreca were well prepared, had massed their troops in a strong position and had under their command the greater part of the existing forces of the president. But the splendid fighting qualities of the Congressional troops and the superior generalship of their leaders prevailed in the end over every obstacle and resulted in victory for the rebels. The government army was practically annihilated, 941 men were killed, including Barbosa and his second in command, and 2,402 wounded. The Congressional army lost over 1,800 men.

Valparaiso was occupied the same evening and three days later the victorious insurgents entered Santiago and assumed the government of the republic soon afterwards. There was no further fighting, for so great was the effect of the battles of Concon and La Placilla that even the Coquimbo troops surrendered without firing a shot.

Aftermath

[edit]After the battle of Placilla it was clear to President Balmaceda that he could no longer hope to find sufficient strength amongst his adherents to maintain himself in power, and in view of the rapid approach of the rebel army he abandoned his official duties to seek asylum in the Argentine legation. On 29 August, he officially handed power to General Manuel Baquedano, who maintained order in Santiago until the arrival of the congressional leaders on 30 August.

The president remained concealed in the Argentine legation until 18 September. On the morning of that date, when the term for which he had been elected president of the republic terminated, he committed suicide by shooting himself. The excuse for this act, put forward in letters written shortly before his end, was that he did not believe the conquerors would give him an impartial trial. The death of Balmaceda finished all cause of contention in Chile, and was the closing act of the most severe and bloodiest struggle that the country had ever witnessed. In the various engagements throughout the conflict more than 10,000 people died, and the joint expenditure of the two governments on military preparations and the purchase of war material exceeded £10,000,000.

The defeat of the presidential forces opened a so-called "pseudo-parliamentary" period in Chile's history, which lasted from 1891 to 1925. As opposed to a "true parliamentary" system, the executive was subject to the legislature but checks and balances of executive power were weakened. The position of President remained as head of state but its powers and control of the government were reduced.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 142–160.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 160..

- Moore, John Bassett. "The Late Chilian Controversy." Political Science Quarterly 8.3 (1893): 467–494. online

- The Chilian Revolution of 1891; Lieut. Sears and Ensign Wells, U.S.N., (Office of Naval Intelligence, Washington, 1893)

- The Capture of Valparaiso, 1891 (Intelligence Department, War Office, London, 1892)

- Taktische Beispiele aus den Kriegen der neuesten Zeit; der Biirgerkrieg in Chile; Hermann Kunz (Berlin, 1901)

- Revista militar de Chile (February–March 1892)

- Der Biirgerkrieg in Chile; Hugo Kunz (Vienna, 1892)

- Militar Wochenblatt (5th supplement, 1892)

- Four Modern Naval Campaigns; Sir W. Laird Clowes (London, 1902)

- Proceedings of U.S. Naval Institute (1894) (for La Placilla)

- Military and naval periodicals of 1892