Action of 9 September 1796

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Action of 9 September 1796 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

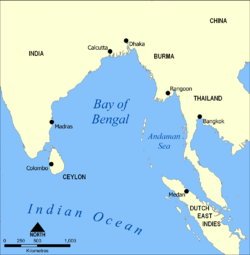

Map of East Indies. Site of battle marked in red | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Pierre César Charles de Sercey | Richard Lucas | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6 frigates | 2 ships of the line | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 42 killed 104 wounded | 24 killed 84 wounded | ||||||

The action of 9 September 1796 was an inconclusive minor naval engagement between small French Navy and British Royal Navy squadrons off northwestern Sumatra, near Banda Aceh, during the French Revolutionary Wars. The French squadron comprised six frigates engaged in commerce raiding against British trade routes passing through captured parts of the Dutch East Indies, and posed a considerable threat to the weakened British naval forces in the region. The British force consisted of two 74-gun ships of the line hastily paired to oppose the eastward advance of the French squadron.

The French squadron, commanded by Contre-amiral Pierre César Charles de Sercey, had left its base on Île de France in July and cruised off Ceylon and Tranquebar before sailing eastwards. Its movement had so far been unopposed, as British forces in the East Indies were concentrated at Simon's Town in the west and Malacca in the east. After raiding the shipping at Banda Aceh on 1 September the squadron sailed eastwards to attack Penang. On 8 September, while the French were removing supplies from a captured British merchant ship east of Banda Aceh, two large sails were spotted. These were HMS Arrogant and HMS Victorious, sent to drive off the French before they could attack the scattered British shipping and ports in the region.

Although the British ships were substantially larger than any individual French vessel, the frigates were more numerous and more manoeuvrable. Neither side could afford to take significant damage in the battle, so each sought to drive the other off rather than achieve an outright victory. On 9 September Sercey's frigates formed a line of battle, successfully engaging first Arrogant and then Victorious and inflicting damage on each while preventing them from supporting one another. The French frigates, particularly Vertu and Seine, also suffered, and by late morning both sides disengaged, the British retiring to Madras for repairs, while Sercey anchored at King's Island in the Mergui Archipelago, eventually sheltering in Batavia.

Background

[edit]At the start of 1796 French and allied forces had been almost completely driven from the Indian Ocean, with most of the colonies of the French-allied Batavian Republic falling to British invasions during 1795.[1] The only significant French presence was on Île de France and a few other nearby islands, from which a squadron of two frigates periodically operated against British trade.[2] The British were so confident of supremacy that they had split their forces, with a large squadron based at Simon's Town in the Cape Colony of Southern Africa under Sir George Keith Elphinstone and a smaller dispersed force operating under Peter Rainier in the Dutch East Indies, based at the captured port of Malacca.[3] The important trading ports of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay were largely undefended, as were the valuable trade routes which supported them.[4]

On 4 March 1796 significant French reinforcements were dispatched when a squadron of four frigates and two corvettes sailed from Rochefort under the command of Contre-amiral Pierre César Charles de Sercey. Both corvettes were lost before the squadron had left the Bay of Biscay and frigate Cocarde was forced to return to port after running aground.[5] After resupplying at La Palma and joining with replacement frigate Vertu, the squadron enjoyed unimpeded progress, seizing several British and Portuguese ships, including two Indiamen in the South Atlantic and Western Indian Ocean.[6] The squadron had not been dispatched primarily to increase the French military presence in the East Indies, but rather to enforce the National Convention's decree that Île de France abolish slavery. The agricultural economy of the island depended on slavery to remain profitable, and the colonial committee had simply ignored the decree when it first arrived in 1795.[7] The matter was then taken up by the Committee for Public Safety, which sent agents Baco and Burnel to ensure the ruling was carried out, supported by 800 soldiers under General François-Louis Magallon.[8]

On arrival at Port Louis on 18 June, the agents were confronted by a large body of heavily armed militia opposed to the abolition of slavery. Although they ordered Magallon to attack the islanders, the general refused and the agents were sent back to sea in a small corvette, eventually returning to Europe.[9] Sercey remained in the East Indies, refitting his ships and joining his squadron to that already at Île de France. This force he divided, sending Preneuse and a corvette to patrol the Mozambique Channel.[10] The remaining six frigates, comprising Vertu, Régénérée, Forte, Seine, Prudente and Cybèle, with the privateer schooner Alerte, Sercey took eastwards on 14 July, towards the Bay of Bengal.[11]

Sercey was unaware of how scattered British forces were in the region, and sent Alerte to scout ahead after the squadron arrived off Ceylon. Captain Drieu of Alerte made the miscalculation of attacking a ship on 14 August which turned out to be the 28-gun British dispatch frigate HMS Carysfort, and on board Alerte the British captors discovered documents revealing the exact extent of Sercey's strength and intentions.[12] Carysfort's captain was unable to warn any allied ships as his small frigate was the only British warship in the Bay of Bengal, and so he instead arranged for false information to be passed to Sercey regarding a fictional British battle squadron at Madras. This was sufficient to deter Sercey from lingering in the area, and after a raiding sweep along the coast to Tranquebar his squadron sailed eastwards once more.[13]

On 1 September Sercey raided Banda Aceh, capturing a number of merchant ships and on 7 September seized the small merchant ship Favourite off the northeastern coast of Sumatra en route to attack the British port of Penang. The following morning, as his squadron transferred rice from the prize, two large sails appeared in the distance to the northeast.[13] These sails belonged to the 74-gun British ships of the line HMS Arrogant under Captain Richard Lucas and HMS Victorious under Captain William Clark. These ships had been sent to the East Indies from the Cape at the start of August on orders from Elphinstone and were engaged in protecting British trade with China. When news reached Penang that Sercey was in the region, Lucas ordered Clark to join him in a search for the French in the Straits of Malacca.[14]

Battle

[edit]Lucas first sighted the French at 06:00 on 8 September, approximately 24 nautical miles (44 km) east of Point Pedro, the northeastern tip of Sumatra. By 10:00 Sercey had determined that the new arrivals were probably hostile and formed his frigates into a line of battle, tacking to investigate.[15] Lucas and Clark conferred at 14:00, Clark believing that two of the ships were French ships of the line while Lucas correctly insisted that they were six frigates, accompanied by the captured East Indiaman Triton. The captains agreed to pursue the French and bring them to battle when possible.[15] At 14:30, Forte determined that the approaching ships were British ships of the line and Sercey turned away, unwilling to risk suffering severe damage in a pointless engagement with two such powerful opponents. Sercey's squadron attempted to seek shelter in coastal waters, closely pursued by Lucas' ships; by 21:30 the British were just 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) behind the French.[16]

By the morning of 9 September the wind had dropped and the French frigates were sailing in line slowly eastwards along the northern coast of Sumatra, the British ships close behind. With battle inevitable, Sercey gave orders at 06:00 for his line to put about and seize the weather gage while Lucas led Arrogant on a path to intercept. At 07:25 Lucas opened fire on the lead French ship Vertu at the range of 700 yards (640 m).[17] The British ship was able to fire two broadsides before Captain Lhermitte on Vertu could reply, the first French volley snatching away the ensign. Arrogant then progressively came under fire from the whole French line, as Seine, Forte and Cybèle passed, the more distant Régénéree and Prudente joining the fusillade. During this exchange of fire both Arrogant and Vertu suffered damage to their sails and rigging, the Arrogant temporarily unmaneuverable as the winds dropped almost completely.[17]

Victorious was also hit, Captain Clark forced to retire wounded after being struck in the thigh by debris at 08:00. At 08:30 the rearmost French ship, Prudente, passed out of range of Arrogant leaving the ship isolated. With Lucas unable to participate, Lieutenant William Waller on Victorious assumed command and ordered his ship to engage the French at 08:40, a string of signal flags hoisted on Arrogant unreadable in the light winds.[18] Victorious was soon surrounded by the French, with two frigates on the port bow and four on the port beam, all firing into the ship of the line from approximately 900 yards (820 m). By 10:15, when the wind suddenly returned, Victorious had been badly damaged. Using the wind to turn towards the distant Arrogant, Waller exposed his ship's stern and was repeatedly raked. The winds remained unreliable, and Victorious took further damage for the next half-hour, the French ships remaining outside the arcs of fire from the British ship.[19]

The damage Vertu had taken early in the combat rendered Lhermitte unable to continue the action, and his ship gradually fell out of the line to the south. Captain Pierre Julien Tréhouart turned Cybèle away too, using sweeps to reach Vertu and take the ship under tow. With Vertu secured and Arrogant slowly coming back into range,[20] Sercey ordered his squadron to turn away to the north at 10:55, the last shots fired at long range from Victorious at 11:15.[18]

Combatant summary

[edit]In this table, "Guns" refers to all cannon carried by the ship, including the maindeck guns which were taken into consideration when calculating its rate, as well as any carronades carried aboard.[21] Broadside weight records the combined weight of shot which could be fired in a single simultaneous discharge of an entire broadside.

| Ship | Commander | Navy | Guns | Broadside weight | Complement | Casualties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Wounded | Total | |||||||

| HMS Arrogant | Captain Richard Lucas | 74 | 838 lb (380 kg) | 584 | 7 | 27 | 34 | ||

| HMS Victorious | Captain William Clark | 74 | 838 lb (380 kg) | 493 | 17 | 57 | 74 | ||

| Vertu | Captain Jean-Matthieu-Adrien Lhermitte | 40 | 1,700 lb (770 kg) | 1400 | 9 | 15 | 24 | ||

| Seine | Captain Latour † | 38 | 18 | 44 | 62 | ||||

| Forte | Captain Hubert Le Loup de Beaulieu | 44 | 6 | 17 | 23 | ||||

| Cybèle | Captain Pierre Julien Tréhouart | 40 | 4 | 13 | 17 | ||||

| Régénérée | Captain Jean-Baptiste Philibert Willaumez | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Prudente | Captain Charles René Magon de Médine | 32 | 3 | 9 | 12 | ||||

| Source: Clowes, p. 503. Clowes conflates figures for broadside weight, crews and casualties. Crew and casualty details from James, pp. 353–354. | |||||||||

Aftermath

[edit]Losses on both sides were heavy. Arrogant had been damaged early in the battle and lost seven killed and 27 wounded while Victorious which bore the brunt of the French attack, suffered 17 killed and 57 wounded, the latter including Clark. Neither British ship was in sufficient repair to continue the engagement; Arrogant had several cannon dismounted and her sails and rigging were tattered. Victorious was less badly damaged, but had more than one in five of the crew unfit for duty.[18] All of the French ships suffered damage and casualties, although Régénérée reported no losses in the aftermath. Vertu was damaged early on and took 24 casualties, Seine was hit by heavy fire later in the battle and lost 62 dead and wounded, with the captain among the former. The remainder of the squadron suffered lighter losses, with 12 on Prudente, 17 on Cybèle and 23 on Forte.[22]

Lucas and Clark remained off Sumatra until basic repairs could be completed before Arrogant then took Victorious under tow, leading the damaged ship back to Penang and then Madras for repairs, arriving on 6 October.[22] Sercey abandoned plans for an attack on Penang and sailed northwards to King's Island in the Mergui Archipelago. There his ships underwent extensive repairs, some even replacing their lower masts.[20] In October the squadron swept eastwards to the Ceylon coast before turning back west towards Batavia, where Sercey hoped the supply depots would provide more support than those on Île de France. The squadron remained at Batavia throughout the winter, ceding control of the Indian Ocean trade routes to the British.[23]

The action has been described as inconclusive by British historian C. Northcote Parkinson as neither side could achieve a decisive result. Parkinson is also scathing of his criticism of both Clark and Waller, accusing them of failing to properly to prepare for battle or effectively manoeuvre their ship under fire.[23] During the battle neither side had actually sought a decisive result, both unwilling to risk damage which would jeopardise their mission. Sercey's orders were to raid British trade routes, not to engage heavy warships and suffer the consequent damage: the battle severely curtailed his opportunities to prey on British merchant shipping in the East Indies during 1796.[16][20] Lucas sought to block Sercey's passage through the Malacca Straits, but was aware that his ships, though large and powerful, were outnumbered and outgunned in the engagement, particularly given the size of the main French line, composed of ships with batteries of 18-pounder long guns and including Forte, one of the most massive frigates then at sea.[23] William James considers that had the winds been more favourable Lucas might have been able to cut off and capture at least two French frigates, but had Sercey attempted a boarding action against the ships of the line his more numerous crews would probably have successfully seized them.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ Clowes, p.294

- ^ James, p.196

- ^ Parkinson, p.95

- ^ Parkinson, p.96

- ^ James, p.347

- ^ James, p.348

- ^ Parkinson, p.97

- ^ Parkinson, p.98

- ^ Parkinson, p.99

- ^ Parkinson, p.100

- ^ Roche, p.33

- ^ James, p.349

- ^ a b Parkinson, p.101

- ^ Parkinson, p.102

- ^ a b James, p.350

- ^ a b James, p.351

- ^ a b James, p.352

- ^ a b c James, p.353

- ^ Clowes, p.503

- ^ a b c Parkinson, p.105

- ^ James, p.32

- ^ a b c James, p.354

- ^ a b c Parkinson, p.104

Bibliography

[edit]- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 1, 1793–1796. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-905-0.

- Ladimir, F.; Moreau, E. (1856). Campagnes, thriomphes, revers, désastres et guerres civiles des Français de 1792 à la paix de 1856 (in French). Vol. 5. Paris: Librairie Populaire des Villes et des Campagnes. OCLC 162525060.

- Parkinson, C. Northcote (1954). War in the Eastern Seas, 1793 – 1815. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. OCLC 1000708.

- Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours 1 1671 - 1870 (in French). Roche. ISBN 978-2-9525917-0-6.