Ahmedabad

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Ahmedabad Karnavati, Ashawal | |

|---|---|

| Amdavad | |

Skyline of SG Highway Ahmedabad Aerial View | |

| Nickname(s): Manchester of the East, Heritage City of India | |

| Coordinates: 23°01′21″N 72°34′17″E / 23.02250°N 72.57139°E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| District | Ahmedabad |

| Establishment | 11th Century as Ashaval |

| Founded by | King Asha Bhil |

| Named for | Ahmad Shah I |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | Amdavad Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Pratibha Jain (BJP)[1] |

| • Deputy Mayor | Jatin Patel (BJP)[1] |

| • Municipal commissioner | M. Thennarasan[2] |

| • Police commissioner | GS Malik IPS[3] |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 1,060.95 km2 (409.64 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,866 km2 (720 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 8th in India (1st in Gujarat State) |

| • City [6] | 466 km2 (180 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 69.65 m (228.51 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Estimate (2024)[8] | 8,854,440 |

| • Urban | 6,357,693 |

| • Urban density | 6,000/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| • City | 5,577,940 |

| • City density | 12,000/km2 (31,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Amdavadi, Ahmedabadi |

| Language | |

| • Official | Gujarati |

| • Additional official | English |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 3800xx |

| Area code | +9179xxxxxxxx |

| Vehicle registration | GJ-01 (west), GJ-27 (East), GJ-38 Bavla (Rural)[9] |

| HDI (2016) | 0.867[10] |

| Sex ratio | 1.11[11] ♂/♀ |

| Literacy rate | 85.3%[12] |

| Gross Domestic Product (PPP) (2022-23) | $136.1 Billion [13] |

| Website | ahmedabadcity |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (v) |

| Reference | 1551 |

| Inscription | 2017 (41st Session) |

| Area | 535.7 ha (2.068 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 395 ha (1.53 sq mi) |

Ahmedabad (/ˈɑːmədəbæd, -bɑːd/ AH-mə-də-ba(h)d), also spelled as Amdavad, is the most populous city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It is the administrative headquarters of the Ahmedabad district and the seat of the Gujarat High Court. Ahmedabad's population of 5,570,585 (per the 2011 population census) makes it the fifth-most populous city in India,[14] and the encompassing urban agglomeration population estimated at 6,357,693 is the seventh-most populous in India. Ahmedabad's 2024 population is now estimated at 8,854,444.[15] Ahmedabad is located near the banks of the Sabarmati River,[16] 25 km (16 mi)[17] from the capital of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, also known as its twin city.[18]

Ahmedabad has emerged as an important economic and industrial hub in India. It is the second-largest producer of cotton in India, due to which it was known as the 'Manchester of India' along with Kanpur. Ahmedabad's stock exchange (before it was shut down in 2018) was the country's second oldest. Cricket is a popular sport in Ahmedabad; a newly built stadium, called Narendra Modi Stadium, at Motera can accommodate 132,000 spectators, making it the largest stadium in the world. The world-class Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Sports Enclave is currently under construction and once complete, it will be one of the biggest sports centers (Sports City) in India. The effects of the liberalisation of the Indian economy have energised the city's economy towards tertiary sector activities such as commerce, communication and construction.[19] Ahmedabad's increasing population has resulted in an increase in the construction and housing industries, resulting in the development of skyscrapers.[20]

In 2010, Ahmedabad was ranked third in Forbes's list of fastest growing cities of the decade.[21] In 2012, The Times of India chose Ahmedabad as India's best city to live in.[22] The gross domestic product of Ahmedabad metro was estimated at $136.1 billion in 2023.[23][24] In 2020, Ahmedabad was ranked as the third-best city in India to live by the Ease of Living Index.[25] In July 2022, Time magazine included Ahmedabad in its list of world's 50 greatest places of 2022.[26]

Ahmedabad has been selected as one of the hundred Indian cities to be developed as a smart city under the Government of India's flagship Smart Cities Mission.[27] In July 2017, the historic city of Ahmedabad, or Old Ahmedabad, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage City.[28]

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]Based on relics found in several neighbourhoods of the old city and on writings of the Persian historian al-Biruni, it is surmised that an early Bhil tribal group settlement was known as Ashaval.[29][30]

According to Merutunga, Karna, the Chaulukya (Solanki) ruler of Anhilvada (modern Patan), successfully launched a military campaign against Ashaval and founded a city nearby called Karnavati.[29] The location of Karnavati is not definitively known.[30] References from the 14th and 15th centuries mention Ashaval but do not mention Karnavati.[30]

Ahmad Shah I of the Gujarat Sultanate transferred its capital from Anhilvada to Ashaval in 1411 CE; as was custom, the city was subsequently renamed Ahmedabad after the Sultan.[31]

Early history

[edit]The area around Ahmedabad has been inhabited since the 11th century, when it was known as Ashaval.[32] At that time, Karna, the Chaulukya (Solanki) ruler of Anhilwara (modern Patan), waged a successful war against the Bhil king of Ashaval,[33] and established a city called Karnavati on the banks of the Sabarmati.[34] Solanki rule lasted until the 13th century, when Gujarat came under the control of the Vaghela dynasty of Dholka. Gujarat subsequently came under the control of the Delhi Sultanate in the 14th century. However, by the earlier 15th century, the local Muslim governor Zafar Khan Muzaffar established his independence from the Delhi Sultanate and crowned himself Sultan of Gujarat as Muzaffar Shah I, thereby founding the Muzaffarid dynasty.[35][36][37] In 1411, the area came under the control of his grandson, Sultan Ahmed Shah, who selected the forested area along the banks of the Sabarmati river for his new capital. He laid the foundation of a new walled city near Karnavati and named it Ahmedabad after himself.[38][39] According to other versions, he named the city after four Muslim saints in the area who all had the name Ahmed.[40] Ahmed Shah I laid the foundation of the city on 26 February 1411[41] (at 1.20 pm, Thursday, the second day of Dhu al-Qi'dah, Hijri year 813[42]) at Manek Burj. Manek Burj is named after the legendary 15th-century Hindu saint, Maneknath, who intervened to help Ahmed Shah I build Bhadra Fort in 1411.[38][43][44][45] Ahmed Shah I chose it as the new capital on 4 March 1411.[46] Chandan and Rajesh Nath, 13th generation descendants of Saint Maneknath, perform puja and hoist the flag on Manek Burj on Ahmedabad's foundation day and for the Vijayadashami festival every year.[38][44][47][48]

In 1487, Mahmud Begada, the grandson of Ahmed Shah, fortified the city with an outer wall 10 km (6.2 mi) in circumference and consisting of twelve gates, 189 bastions, and over 6,000 battlements.[49] In 1535 Humayun briefly occupied Ahmedabad after capturing Champaner when the ruler of Gujarat, Bahadur Shah, fled to Diu.[50] Ahmedabad was then reoccupied by the Muzaffarid dynasty until 1573 when Gujarat was conquered by the Mughal emperor Akbar. During the Mughal reign, Ahmedabad became one of the Empire's thriving centres of trade, mainly in textiles, which were exported as far as Europe. The Mughal ruler Shah Jahan spent the prime of his life in the city, sponsoring the construction of the Moti Shahi Mahal in Shahibaug. The Deccan Famine of 1630–32 affected the city, as did famines in 1650 and 1686.[51] Ahmedabad remained the provincial headquarters of the Mughals until 1758, when they surrendered the city to the Marathas.[52]

Modern history

[edit]

During the period of Maratha Empire governance, the city became the centre of a conflict between the Peshwa of Poona and the Gaekwad of Baroda.[53] In 1780, during the First Anglo-Maratha War, a British force under James Hartley stormed and captured Ahmedabad, but it was handed back to the Marathas at the end of the war. The British East India Company took over the city in 1818 during the Third Anglo-Maratha War.[40] A military cantonment was established in 1824 and a municipal government in 1858.[40] Incorporated into the Bombay Presidency during British rule, Ahmedabad became one of the most important cities in the Gujarat region. In 1864, a railway link between Ahmedabad and Mumbai (then Bombay) was established by the Bombay, Baroda, and Central India Railway (BB&CI), enabling traffic and trade between northern and southern India via the city.[40] Over time, the city established itself as the home of a developing textile industry, which earned it the nickname "Manchester of the East".[54]

The Indian independence movement developed roots in the city when Mahatma Gandhi established two ashrams – the Kochrab Ashram near Paldi in 1915 and the Satyagraha Ashram (now Sabarmati Ashram) on the banks of the Sabarmati in 1917 – which would become centres of nationalist activities.[40][55] During the mass protests against the Rowlatt Act in 1919, textile workers burned down 51 government buildings across the city in protest at a British attempt to extend wartime regulations after the First World War. In the 1920s, textile workers and teachers went on strike, demanding civil rights and better pay and working conditions. In 1930, Gandhi initiated the Salt Satyagraha from Ahmedabad by embarking from his ashram on the Dandi Salt March. The city's administration and economic institutions were rendered inoperative in the early 1930s by the large numbers of people who took to the streets in peaceful protests, and again in 1942 during the Quit India Movement.

Post-Independence

[edit]Following independence and the partition of India in 1947, the city was scarred by the intense communal violence that broke out between Hindus and Muslims in 1947. Ahmedabad was the focus of settlement by Hindu migrants from Pakistan,[56] who expanded the city's population and transformed its demographics and economy.

By 1960, Ahmedabad had become a metropolis with a population of slightly under half a million people, with classical and colonial European-style buildings lining the city's thoroughfares.[57] It was chosen as the capital of Gujarat after the partition of the State of Bombay on 1 May 1960.[58] During this period, a large number of educational and research institutions were founded in the city, making it a centre for higher education, science, and technology.[59] Ahmedabad's economic base became more diverse with the establishment of heavy and chemical industry during the same period. Many countries sought to emulate India's economic planning strategy and one of them, South Korea, copied Ahmedabad's second "Five-Year Plan".[60] Post independence Ahmedabad has seen development in manufacturing and infrastructure.[61][62]

In the late 1970s, the capital shifted to the newly built city of Gandhinagar. This marked the start of a long period of decline in Ahmedabad, marked by a lack of development. The 1974 Navnirman agitation – a protest against a 20% hike in the hostel food fees at the L.D. College of Engineering in Ahmedabad – snowballed into a movement to remove Chimanbhai Patel, then chief minister of Gujarat.[63] In the 1980s, a reservation policy was introduced in the country, which led to anti-reservation protests in 1981 and 1985. The protests witnessed violent clashes between people belonging to various castes.[64] The city was considerably impacted by the 2001 Gujarat earthquake; up to 50 multi-storey buildings collapsed, killing 752 people and causing much damage.[65] The following year, a three-day period of violence between Hindus and Muslims in the western Indian state of Gujarat, known as the 2002 Gujarat riots, spread to Ahmedabad; in eastern Chamanpura, 69 people were killed in the Gulbarg Society massacre on 28 February 2002.[66] Refugee camps were set up around the city, housing 50,000 Muslims, as well as some small Hindu camps.[67]

The 2008 Ahmedabad bombings, a series of seventeen bomb blasts, killed and injured several people.[68] The terrorist group Harkat-ul-Jihad claimed responsibility for the attacks.[69]

Ahmedabad is one of few cities in India that has hosted the premiers of major economies such as the US, China, and Canada. On 24 February 2020, President Donald Trump became the first US president to visit the city. The event was named Namaste Trump. Earlier, President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited the city.[70][71][72]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Census of India | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

City population increased by 23.43% from 4,519,000 as of the 2001 census of India[update] to 5,577,940 (2,938,985 males and 2,638,955 females resulting in a sex ratio of 898 females per 1,000 males) as of the 2011 census of India[update] making Ahmedabad the fifth most populous city in India.[73][74][75] The urban agglomeration centred upon Ahmedabad had a population of 6,352,254 and was the seventh most populous urban agglomeration in India as of the 2011 census of India[update].[74][76] The population of children aged 0 to 6 was 621,034 (336,063 males and 284,971 females resulting in a child sex ratio of 848 females per 1,000 males) as of the 2011 census of India[update].[73] The city had an average literacy rate of 88.29%, a male literacy rate of 92.30%, and a female literacy rate of 83.85%.[73]

Estimated population of Ahmedabad city is 7,692,000 while that of the urban agglomeration area is 8,772,000 as of 2023.[73] The 2021 census of India has been delayed to 2024-25 and the deadline to freeze administrative boundaries has been extended to 1 January 2024.[77]

Poverty

[edit]In the mid-1970s and early 1980s, the textile mills that were responsible for much of Ahmedabad's wealth faced competition from automation and domestic specialty looms. Several mills closed down, leaving between 40,000 and 50,000 people without a source of income, and many moved into informal settlements in the city centre. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC), the governing and administrative body of the city, simultaneously lost much of its tax base and saw an increased demand for services. In the 1990s, newly emerging pharmaceutical, chemical, and automobile manufacturing industries required skilled labor, so many migrants seeking work ended up in the informal sector and settled in slums.[78]

Ahmedabad has made efforts to reduce poverty and improve the living conditions of poor residents. The urban poverty rate has declined from 28% in 1993–1994 to 10% in 2011–2012.[78] This is partly due to the strengthening of the AMC and its partnership with several civil society organizations (CSOs) representing poor residents. Through projects and programs, the AMC has provided utilities and basic services to slums. However, some challenges remain, and there are still many residents who lack access to sanitation, clean running water, and electricity. Riots, often rooted in religious tensions, threaten the stability of neighborhoods and have caused spatial segregation across religious and caste lines. There remains to be seen a concerted effort to balance pro-poor, inclusive development with national initiatives that aim to create 'global cities' that are the focus of capital investment and technological innovation.

Informal housing and slums

[edit]As of 2011, about 66% of the population lives in formal housing, with the other 34% living in slums or chawls, which are tenements for industrial workers. There are approximately 700 slum settlements in Ahmedabad and 11% of the total housing stock is public housing. The population of Ahmedabad has increased while the housing stock has remained generally constant, and this has led to a rise in density of both formal and informal housing and a more economical usage of existing space. The Indian census estimates that the Ahmedabad slum population was 25.6% of the total population in 1991 and had decreased to 4.5% in 2011, but these numbers are contested and local entities maintain that the census underestimates informal populations. There is a consensus that there has been a reduction in the percentage of the population that lives in slum settlements, and that there has also been a general improvement in living conditions for slum residents.[78][needs update?]

Slum Networking Project

[edit]

In the 1990s, the AMC faced increased slum populations. They found that residents were willing and able to pay for legal connections to water, sewage, and electricity, but because of tenure issues, they were paying higher prices for low-quality, informal connections. To address this, beginning in 1995, the AMC partnered with civil society organizations to create the Slum Networking Project (SNP) to improve basic services in 60 slums, benefitting approximately 13,000 households.[78] This project, also known as Parivartan (Change), involved participatory planning in which slum residents were partners alongside AMC, private institutions, microfinance lenders, and local NGOs. The goal of the program was to provide both physical infrastructure (including water supply, sewers, individual toilets, paved roads, storm drainage, and tree planting) and community development (i.e. the formation of resident associations, women's groups, community health interventions, and vocational training).[79] In addition, participating households were granted a minimum de facto tenure of ten years. The project cost a total of ₹4,350 million. Community members and the private sector each contributed ₹600 million, NGOs provided ₹90 million, and the AMC paid for the rest of the project.[79] Each slum household was responsible for no more than 12% of the cost of upgrading their home.[78]

This project has generally been regarded as a success. Having access to basic services increased the residents' working hours, since most work out of their homes. It also reduced the incidence of illness, particularly water-borne illness, and increased children's rates of school attendance.[80] The SNP received the 2006 UNHABITAT Dubai International Award for Best Practice to Improve the Living Environment.[81] However, concerns remain about the community's responsibility and capacity for the maintenance of the new infrastructure. Additionally, trust was weakened when the AMC demolished two of slums that were upgraded as part of SNP to create recreational parks.[78]

Religion and ethnicity

[edit]According to the 2011 census, Hindus are the predominant religious community in the city comprising 81.56% of the population followed by Muslims (13.51%), Jains (3.62%), Christians (0.85%) and Sikhs (0.24%).[82] Buddhists, people following other religions and those who did not state any religion make up the remainder.

- The Cathedral of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Mirzapur is the cathedral of the Diocese of Ahmedabad.[83][84]

- Most of the residents of Ahmedabad are native Gujaratis. The city is home to some 2,000 Parsis (Zoroastrians),[85] and some 125 members of the Bene Israel Jewish community.[86] There is also one synagogue in the city.[87]

| Religious group | 1891[88] | 1941[89] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Hinduism | 102,619 | 69.14% | 426,498 | 72.13% |

| Islam | 30,946 | 20.85% | 116,301 | 19.67% |

| Jainism | 12,747 | 8.59% | 30,935 | 5.23% |

| Christianity | 1,031 | 0.69% | 8,467 | 1.43% |

| Zoroastrianism | 723 | 0.49% | — | — |

| Animism | 156 | 0.11% | — | — |

| Judaism | 153 | 0.1% | — | — |

| Sikhism | — | — | 825 | 0.14% |

| Other | 37 | 0.02% | 8,241 | 1.39% |

| Total population | 148,412 | 100% | 591,267 | 100% |

Geography

[edit]

Ahmedabad lies in western India at 53 metres (174 ft) above sea level on the banks of the Sabarmati river, in north-central Gujarat. It covers an area of 505 km2 (195 sq mi).[90][91][92][93] The Sabarmati frequently dried up in the summer, leaving only a small stream of water, and the city is in a sandy and dry area. However, with the execution of the Sabarmati River Front Project and Embankment, the waters from the Narmada river have been diverted to the Sabarmati to keep the river flowing throughout the year, thereby eliminating Ahmedabad's water problems. The steady expansion of the Rann of Kutch threatened to increase desertification around the city area and much of the state; however, the Narmada Canal network is expected to alleviate this problem. Except for the small hills of Thaltej-Jodhpur Tekra, the city is almost flat. Three lakes lie within the city's limits—Kankaria, Vastrapur and Chandola. Kankaria, in the neighbourhood of Maninagar, is an artificial lake developed by the Sultan of Gujarat, Qutb-ud-din, in 1451.[94]

According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, the town falls under seismic zone 3, in a scale of 2 to 5 (in order of increasing vulnerability to earthquakes).[95]

Ahmedabad is divided by the Sabarmati into two physically distinct eastern and western regions. The eastern bank of the river houses the old city, which includes the central town of Bhadra. This part of Ahmedabad is characterised by packed bazaars, the pol system of closely clustered buildings, and numerous places of worship.[96] A pol (pronounced as pole) is a housing cluster which comprises many families of a particular group, linked by caste, profession, or religion.[97][98] This is a list of pols in the old walled city[97] of Ahmedabad in Gujarat, India. Heritage of these pols[99] has helped Ahmedabad gain a place in UNESCO's Tentative Lists, in selection criteria II, III and IV.[100] The secretary-general of EuroIndia Centre quoted that if 12,000 homes of Ahmedabad are restored they could be very helpful in promoting heritage tourism and its allied businesses.[101] The Art Reverie in Moto Sutharvado is Res Artis center. The first pol in Ahmedabad was named Mahurat Pol.[102] The old city also houses the main railway station, the main post office, and some buildings of the Muzaffarid and British eras. The colonial period saw the expansion of the city to the western side of the Sabarmati river, facilitated by the construction of Ellis Bridge in 1875 (and later the modern Nehru Bridge). The western part of the city houses educational institutions, modern buildings, residential areas, shopping malls, multiplexes and new business districts centred around roads such as Ashram Road, C. G. Road, and Sarkhej-Gandhinagar Highway.[103]

The Sabarmati Riverfront is a waterfront area being developed along the banks of the Sabarmati river in Ahmedabad, India. Proposed in the 1960s, its construction began in 2005, and it opened in 2012.[104]

Climate

[edit]Ahmedabad has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh), with marginally less rain than required for a tropical savanna climate. There are three main seasons: summer, monsoon, and winter. Aside from the monsoon season, the climate is extremely dry. The weather is hot from March to June; the average summer maximum is 43 °C (109 °F), and the average minimum is 24 °C (75 °F). From November to February, the average maximum temperature is 30 °C (86 °F), and the average minimum is 13 °C (55 °F). Cold winds from the north are responsible for a mild chill in January. The southwest monsoon brings a humid climate from mid-June to mid-September. The average annual rainfall is about 800 millimetres (31 in), but infrequent heavy torrential rains cause local rivers to flood and it is not uncommon for droughts to occur when the monsoon does not extend as far west as usual. The highest temperature in the city was recorded on 20 May 2016, with it reaching 48 °C (118 °F).[105]

| Climate data for Ahmedabad (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.1 (97.0) | 40.6 (105.1) | 43.9 (111.0) | 46.2 (115.2) | 48.0 (118.4) | 47.2 (117.0) | 42.2 (108.0) | 40.4 (104.7) | 41.7 (107.1) | 42.8 (109.0) | 38.9 (102.0) | 35.6 (96.1) | 48.0 (118.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) | 31.0 (87.8) | 35.8 (96.4) | 39.7 (103.5) | 41.8 (107.2) | 39.0 (102.2) | 33.7 (92.7) | 32.3 (90.1) | 33.6 (92.5) | 35.6 (96.1) | 33.1 (91.6) | 29.5 (85.1) | 34.4 (93.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.1 (68.2) | 22.8 (73.0) | 27.7 (81.9) | 31.9 (89.4) | 34.5 (94.1) | 33.3 (91.9) | 29.8 (85.6) | 28.8 (83.8) | 29.3 (84.7) | 28.8 (83.8) | 25.1 (77.2) | 21.6 (70.9) | 27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 12.4 (54.3) | 14.6 (58.3) | 19.6 (67.3) | 24.2 (75.6) | 27.3 (81.1) | 27.7 (81.9) | 26.1 (79.0) | 25.3 (77.5) | 24.9 (76.8) | 21.8 (71.2) | 17.2 (63.0) | 13.6 (56.5) | 21.2 (70.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) | 2.2 (36.0) | 9.4 (48.9) | 12.8 (55.0) | 19.1 (66.4) | 19.4 (66.9) | 20.4 (68.7) | 21.2 (70.2) | 17.2 (63.0) | 12.6 (54.7) | 8.3 (46.9) | 3.6 (38.5) | 2.2 (36.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 1.2 (0.05) | 0.6 (0.02) | 1.1 (0.04) | 2.5 (0.10) | 5.5 (0.22) | 84.3 (3.32) | 310.1 (12.21) | 242.2 (9.54) | 120.2 (4.73) | 13.1 (0.52) | 1.9 (0.07) | 0.9 (0.04) | 783.6 (30.85) |

| Average rainy days | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 6.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 33.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 35 | 26 | 21 | 20 | 25 | 44 | 69 | 72 | 63 | 43 | 39 | 38 | 67 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 9 (48) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | 14 (57) | 19 (66) | 23 (73) | 25 (77) | 25 (77) | 24 (75) | 19 (66) | 14 (57) | 11 (52) | 17 (62) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 287.3 | 274.3 | 277.5 | 297.2 | 329.6 | 238.3 | 130.1 | 111.4 | 220.6 | 290.7 | 274.1 | 288.6 | 3,019.7 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 6 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 10 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department[106][107][108][109] Time and Date (dewpoints, 2005-2015)[110] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun 1971–1990),[111] IEM ASOS (May record high)[112] Tokyo Climate Center (mean temperatures 1991–2020);[113] Weather Atlas[114][115] | |||||||||||||

Following a heat wave in May 2010, which reached 46.8 °C (116.2 °F) and claimed hundreds of lives,[116] the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC), in partnership with an international coalition of health and academic groups and with support from the Climate & Development Knowledge Network, developed the Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan.[117] Aimed at increasing awareness, sharing information and coordinating responses to reduce the health effects of heat on vulnerable populations, the action plan is the first comprehensive plan in Asia to address the threat of adverse heat on health.[118] It also focuses on community participation, building public awareness of the risks of extreme heat, training medical and community workers to respond to and help prevent heat-related illnesses, and coordinating an interagency emergency response effort when heat waves hit.[119]

Ahmedabad has been ranked 7th best “National Clean Air City” (under Category 1 >10L Population cities) in India according to 'Swachh Vayu Survekshan 2024 Results' [120]

Cityscape

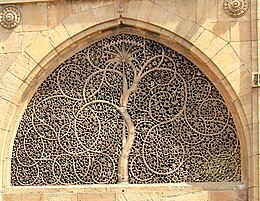

[edit]Early in Ahmedabad's history, under Ahmed Shah, builders fused Hindu craftsmanship with Persian architecture, giving rise to the Indo-Saracenic style.[121] Many mosques in the city were built in this fashion.[121] Sidi Saiyyed Mosque was built in the last year of the Sultanate of Gujarat. It is entirely arched and has ten stone latticework windows or jali on the side and rear arches. Private mansions or haveli from this era have carvings.[97] A pol is a typical housing cluster of Old Ahmedabad.

After independence, modern buildings appeared in Ahmedabad. Architects given commissions in the city included Louis Kahn, who designed the IIM-A; Le Corbusier, who designed the Shodhan and Sarabhai Villas, the Sanskar Kendra and the Mill Owners' Association Building, and Frank Lloyd Wright, who designed the administrative building of Calico Mills and the Calico Dome.[122][123] B. V. Doshi came to the city from Paris to supervise Le Corbusier's works and later set up the School of Architecture (now CEPT). His local works include Sangath, Amdavad ni Gufa, Tagore Memorial Hall and the School of Architecture. Charles Correa, who became a partner of Doshi's, designed the Gandhi Ashram and Achyut Kanvinde, and the Ahmedabad Textile Industry's Research Association complex.[124][125][126] Christopher Charles Benninger's first work, the Alliance Française, is located in the Ellis Bridge area.[127] Anant Raje designed major additions to Louis Kahn's IIM-A campus, namely the Ravi Mathai Auditorium and KLMD.[128]

Some of the most visited gardens in the city include Law Garden, Victoria Garden, and Bal Vatika. Law Garden was named after the College of Law located nearby. Victoria Garden is located at the southern edge of the Bhadra Fort and contains a statue of Queen Victoria. Bal Vatika is a children's park situated on the grounds of Kankaria Lake and houses an amusement park. Other gardens in the city include Parimal Garden, Usmanpura Garden, Prahlad Nagar Garden, and Lal Darwaja Garden.[129] Ahmedabad's Kamla Nehru Zoological Park houses a number of endangered species including flamingoes, caracals, Asiatic wolves, and chinkara.[130]

The Kankaria Lake, built in 1451 CE, is one of the biggest lakes in Ahmedabad.[131] In earlier days, it was known by the name Qutub Hoj or Hauj-e-Kutub.[132] Lal Bahadur Shastri lake in Bapunagar is almost 136,000 square metres. In 2010, another 34 lakes were planned in and around Ahmedabad of which five lakes will be developed by AMC; the other 29 will be developed by the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA).[133] Vastrapur Lake is a small artificial lake located in the western part of Ahmedabad. Beautified by local authorities in 2002, it is surrounded by greenery and paved walkways and has become a popular leisure spot for the citizens.[134] Chandola Lake covers an area of 1200 hectares. It is home to cormorants, painted storks, and spoonbills.[135] During the evening time, many people visit this place and take a leisurely stroll.[136] There is a recently developed lake in Naroda,[137] and there is also the world's largest collection of antique cars in Kathwada at IB farm (Dastan Farm).[138] AMC has also developed the Sabarmati Riverfront.[139]

Looking at the health of traffic police staff deployed near the Pirana dump site, the Ahmedabad City Police is going to install outdoor air purifiers at traffic points so that the deployed staff can breathe fresh air.[140]

- A marble screen from the exterior of the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque

- Hutheesing Jain Derasar main entrance

- Pol area of Old Ahmedabad

- Kankaria Lake, Ahmedabad

Civic administration

[edit]

Ahmedabad is the administrative headquarters of Ahmedabad district and is administered by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC). The AMC was established in July 1950 under the Bombay Provincial Corporation Act of 1949. The AMC commissioner is an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer appointed by the state government who reserves the administrative executive powers, whereas the corporation is headed by the mayor of Ahmedabad. The city residents elect the 192 municipal councillors by popular vote and the elected councillors select the deputy mayor and mayor of the city. The mayor, Bijal Patel, was appointed on 14 June 2018.[141] The administrative responsibilities of the AMC are water and sewerage services, primary education, health services, fire services, public transport and the city's infrastructure.[93] AMC was ranked 9th out of 21 cities for "the best governance & administrative practices in India in 2014. It scored 3.4 out of 10 compared to the national average of 3.3."[142] Ahmedabad registers two accidents per hour.[143]

The city is divided into seven zones constituting 48 wards.[144][145] The city's urban and suburban areas are administered by the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA).

- The city is represented by two elected members of parliament in the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Indian Parliament) and 21 members of the Legislative Assembly at the Gujarat Vidhan Sabha (state legislative assembly).

- The Gujarat High Court is located in Ahmedabad, making the city the judicial capital of Gujarat.[146]

- Law enforcement and public safety is maintained by the Ahmedabad City Police, which is headed by the Police Commissioner, an Indian Police Service (IPS) officer.[147]

Public services

[edit]- Health services are primarily provided at Ahmedabad civil hospital, the largest civil hospital in Asia.[148]

- Electricity is generated and distributed by Torrent Power Limited, which is owned and operated by the Ahmedabad Electricity Company (a previously state-run corporation).[149] Ahmedabad is one of the few cities in India where the power sector is privatised.[150]

Culture

[edit]

Ahmedabad is known for its rich architecture, traditional housing designs, community-oriented settlement patterns, urban structure, as well as its unique crafts and mercantile culture.[151] The people of Ahmedabad celebrate a vast range of festivals. Celebrations and observances include Uttarayan, a harvest festival which involves kite-flying on 14 and 15 January. The nine nights of Navratri are celebrated with people performing Garba, the most popular folk dance of Gujarat, at venues across the city. The annual Rath Yatra procession takes place on the Ashadh-sud-bij date of the Hindu calendar at the Jagannath Temple. Festivals like Diwali, Holi, Christmas, and Muharram (pan-Indian festivals) are also celebrated.[152][153]

Cuisine

[edit]One of the most popular dishes in Ahmedabad is the Gujarati thali, which was first served commercially by Chandvilas Hotel in 1900.[154] It consists of roti (chapati), dal, rice, and shaak (cooked vegetables, sometimes with curry), with accompaniments of pickles and roasted papads. Sweet dishes include laddoo, mango, and vedhmi. Dhoklas, theplas, and dhebras are other popularly consumed dishes in Ahmedabad.[155] Beverages include buttermilk and tea. Drinking alcohol is legally banned in Ahmedabad as Gujarat is a 'dry' state.[156]

There are many restaurants, which serve Indian and international cuisines. Most of food outlets serve only vegetarian food, as there exists a strong tradition of vegetarianism that has been maintained by the city's Jain and Hindu communities over centuries.[157] The first all-vegetarian Pizza Hut in the world opened in Ahmedabad.[158] KFC has a separate staff uniform for serving vegetarian items and prepares vegetarian food in a separate kitchen,[159][160] as does McDonald's.[161][162] Ahmedabad has a number of restaurants serving typical Mughlai non-vegetarian food in older areas like Bhatiyar Gali, Kalupur and Jamalpur.[163] Manek Chowk is an open square near the centre of the city that functions as a vegetable market in the morning and a jewellery market in the afternoon. However, it is best known for becoming a vast congregation of food stalls in the evening, which sell local street food. It is named after the Hindu saint Baba Maneknath.[164]

Art & Crafts

[edit]Parts of Ahmedabad are known for their folk art. The artisans of Rangeela pol make tie-dyed bandhinis, while the cobbler shops of Madhupura sell traditional mojdi (also known as mojri) footwear. Idols of the Hindu deity Ganesha and other religious icons are made in large numbers by artisans in the Gulbai Tekra area. In 2019, there was a surge in demand for eco-friendly idols due to increased awareness surrounding the effects of submerging the traditional plaster-of-paris idols in the Sabarmati river.[165] The shops at the Law Garden sell mirrorwork handicrafts.[129]

Three main literary institutions were established in Ahmedabad for the promotion of Gujarati literature: Gujarat Vidhya Sabha, Gujarati Sahitya Parishad and Gujarat Sahitya Sabha. Saptak School of Music festival is held in the first week of the new year. This event was inaugurated by Ravi Shankar.[166][167]

The Sanskar Kendra, one of the several buildings in Ahmedabad designed by Le Corbusier, is a museum displaying the city's history, art, culture, and architecture. The Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya and the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial have permanent displays of photographs, documents, and other articles relating to the Gujarat-born Indian independence movement leaders Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The Calico Museum of Textiles has a large collection of Indian and international fabrics, garments, and textiles.[168] The Hazrat Pir Mohammad Shah Library has a collection of rare original manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Sindhi, and Turkish.[169] The Vechaar Utensils Museum has stainless steel, glass, brass, copper, bronze, zinc, and German silver tools on display.[170][171] The Conflictorium is an interactive installation space that explores conflict in society through art.

The Shreyas Foundation has four museums on its campus. The Shreyas Folk Museum (Lokayatan Museum) has art forms and artefacts from various Gujarati communities. The Kalpana Mangaldas Children's Museum has a collection of toys, puppets, dance and drama costumes, coins, and a repository of recorded music from traditional shows from all over the world. Kahani houses photographs of fairs and festivals of Gujarat. Sangeeta Vadyakhand is a gallery of musical instruments from India and other countries.[172][173][174]

The L. D. Institute of Indology houses 76,000 hand-written Jain manuscripts with 500 illustrated versions and 45,000 printed books, making it the largest collection of Jain scripts, Indian sculptures, terracottas, miniature paintings, cloth paintings, painted scrolls, bronzes, woodwork, Indian coins, textiles and decorative art, paintings of Rabindranath Tagore, and art of Nepal and Tibet.[175] The N. C. Mehta Gallery of Miniature Paintings has a collection of ornate miniature paintings and manuscripts from all over India.[176]

In 1949, the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts was established by the scientist Dr. Vikram Sarabhai and his wife, Bharat Natyam dancer Mrinalini Sarabhai. Its influence has led Ahmedabad to become a centre of Indian classical dance.[177]

Education

[edit]

Primary and secondary education

[edit]Schools in Ahmedabad are either run publicly by the AMC, or privately by entities, trusts, and corporations. The majority of schools are affiliated with the Gujarat Secondary and Higher Secondary Education Board, although some are affiliated with the Central Board for Secondary Education, Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations, International Baccalaureate, and National Institute of Open School.

Higher education and research organizations

[edit]

Several institutions of higher education with a focus on engineering, management, and design are located in Ahmedabad.[citation needed] The oldest higher educational institution is Gujarat College.[178] Among the universities in Ahmedabad, Gujarat University is a collegiate university established in 1949[179] and has 286 affiliated colleges, 22 recognized institutions, and 36 postgraduate departments.[180] Indira Gandhi National Open University, commonly known as IGNOU is a public university in India and having an active regional centre in Ahmedabad region to offer 290 ODL programs and 40+ online programs to the students lives in the city.[181] Other state universities in the city include Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University,[182] Gujarat Technological University,[183] and Kaushalya Skill University.[184] Gujarat Vidyapith, located near the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium, was founded by Mahatma Gandhi in 1920 and became a deemed university in 1963.[185]

Private universities located in the city include Ahmedabad University,[186] CEPT University (formerly Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology),[187] Indus University,[188] Nirma University,[189] GLS University,[190] and Silver Oak University.[191] Two Institutes of National Importance are located in the city—Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad[192] and National Institute of Design.[193]

Other institutions located in the city include the Physical Research Laboratory, which was established in 1947 by the physicist and astronomer Vikram Sarabhai.[194] It is an autonomous research institute under the Department of Space with a focus on research in astronomy, experimental and theoretical physics, and earth sciences.[194] The Ahmedabad Textile Industry's Research Association (ATIRA), registered in 1947, is an autonomous, non-profit association engaged in operational and applied research in the textile industry.[195]

Media

[edit]

Newspapers in Ahmedabad include English dailies such as The Times of India, Indian Express, DNA, The Economic Times, The Financial Express, Ahmedabad Mirror, and Metro.[196] Newspapers in other languages include Divya Bhaskar, Gujarat Samachar, Sandesh, Rajasthan Patrika, Sambhaav, and Aankhodekhi.[196] The city is home to the historic Navajivan Publishing House, which was founded in 1919 by Mahatma Gandhi.[197]

The state-owned All India Radio Ahmedabad is broadcast both on medium wave bands and FM bands (96.7 MHz) in the city.[198] It competes with five private local FM stations: Radio City (91.1 MHz), Red FM (93.5 MHz), My FM (94.3 MHz), Radio One (95.0 MHz), Radio Mirchi (98.3 MHz) and Mirchi Love (104 MHz). Gyan Vani (104.5 MHz) is an educational FM radio station run under the media co-operation model.[199] In March 2012, Gujarat University started a campus radio service on 90.8 MHz, which was the first of its kind in the state and the fifth in India.[200]

The state-owned television broadcaster Doordarshan provides free terrestrial channels, while three multi system operators—InCablenet, Siti Cable, and GTPL—provide a mix of Gujarati, Hindi, English, and other regional channels via cable.[201] Telephone services are provided by landline and mobile operators such as Jio, BSNL Mobile, Airtel, and Vodafone Idea.[202]

Economy

[edit]

The gross domestic product of Ahmedabad was estimated at $64 billion in 2014.[203][204] The RBI ranked Ahmedabad as the seventh largest deposit centre and seventh largest credit centre nationwide as of June 2012.[205] In the 19th century, the textile and garments industry received strong capital investment. On 30 May 1861 Ranchhodlal Chhotalal founded the first Indian textile mill, the Ahmedabad Spinning and Weaving Company Limited,[206] followed by the establishment of a series of textile mills such as Calico Mills, Bagicha Mills and Arvind Mills. By 1905 there were about 33 textile mills in the city.[207] The textile industry underwent rapid expansion during the First World War and benefited from the influence of Mahatma Gandhi's Swadeshi movement, which promoted the purchase of Indian-made goods.[208] Ahmedabad was known as the "Manchester of the East" for its textile industry.[55] The city is the largest supplier of denim and one of the largest exporters of gemstones and jewellery in India.[19] The automobile industry is also important to the city; after Tata's Nano project, Ford, Suzuki and Peugeot have established engine and vehicle manufacturing plants near Ahmedabad.[209][210][211]

The Ahmedabad Stock Exchange, located in the Ambavadi area of the city, is India's second oldest stock exchange. It is now defunct.[212] Two of the biggest pharmaceutical companies of India—Zydus Lifesciences and Torrent Pharmaceuticals—are based in the city. The Nirma group of industries, which runs detergent and chemical industrial units, has its corporate headquarters in the city. The city houses the corporate headquarters of the Adani Group, a multinational trading and infrastructure development company.[213] The Sardar Sarovar Project of dams and canals has improved the supply of potable water and electricity for the city.[214] The information technology industry has developed significantly in Ahmedabad, with companies such as Tata Consultancy Services opening offices in the city.[215] A NASSCOM survey in 2002 on the "Super Nine Indian Destinations" for IT-enabled services ranked Ahmedabad fifth among the top nine most competitive cities in the country.[216] The city's educational and industrial institutions have attracted students and young skilled workers from the rest of India.[217] Ahmedabad houses other major Indian corporates such as Cadila Healthcare, Rasna, Wagh Bakri, Cadila Pharmaceuticals, and Intas Biopharmaceuticals. Ahmedabad is the second largest cotton textile centre in India after Mumbai and the largest in Gujarat.[218] Many cotton manufacturing units operate in and around Ahmedabad.[219][220][221][222][223] Textiles are one of the major industries of the city.[224] Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation has acquired land in Sanand taluka of Ahmedabad to set up three new industrial estates.[225]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Transportation

[edit]Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport, located in Hansol and operated by the Adani Group, is Ahmedabad's principal airport.[226] The Dholera International Airport, located 110 km southwest of central Ahmedabad in Navagam village, is currently under construction and expects completion of its first phase by 2025.[227]

The Ahmedabad railway division, an operating division under the Western Railway zone of Indian Railways, is headquartered in the city.[228] Ahmedabad Junction railway station, locally known as Kalupur railway station,[229] is Ahmedabad's primary and Gujarat's busiest railway hub.[230] Other major railway stations that service the city include Chandlodiya,[231] Gandhigram,[232] Maninagar,[233] and Sabarmati Junction.[234][235]

Public transit includes the Ahmedabad Metro, a rapid transit system inaugurated in March 2019 with 40 km of track on two lines (East-West and North-South) and a daily ridership of 90,000.[236] Phase 2 of the Ahmedabad Metro—connecting Motera Stadium northwards to Mahatma Mandir in Gandhinagar—began construction in February 2021 and is expected to be complete by 2026.[237] Other public transit options include the Ahmedabad BRTS, also known as Janmarg (people's way), a bus rapid transit system inaugurated in October 2009 with a total fleet of 325 buses over 19 routes and a daily ridership of 190,000.[238] Bus transportation is also provided by Ahmedabad Municipal Transport Service (AMTS) with 700 buses over 149 routes.[238] Both the Ahmedabad BRTS and the AMTS are overseen by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation.[239][240] Ahmedabad also has self drive car rental service provided by private companies like Just Drive Self Drive Cars.

The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation introduced "AmdaBike," a public bicycle sharing system, in December 2019 to improve last mile connectivity.[241] MYBYK is the main service provider for AmdaBike with 300 bicycle stations—including at Ahmedabad BRTS stations—and 4,000 bicycles.[241]

Road

[edit]National Highway 48 passes through Ahmedabad and connects it with New Delhi and Mumbai. The National Highway 147 also links Ahmedabad to Gandhinagar. It is connected to Vadodara through National Expressway 1, a 94 km (58 mi)-long expressway with two exits. This expressway is part of the Golden Quadrilateral project.[242]

In 2001, Ahmedabad was ranked as the most-polluted city in India out of 85 cities by the Central Pollution Control Board. The Gujarat Pollution Control Board gave auto rickshaw drivers an incentive of ₹10,000 to convert the fuel of all 37,733 auto rickshaws in Ahmedabad to cleaner-burning compressed natural gas to reduce pollution. As a result, in 2008, Ahmedabad was ranked as the 50th most-polluted city in India.[243]

Sports

[edit]

Cricket is one of the most popular sports in the city.[244] Narendra Modi Stadium, also known as the Motera Stadium, originally Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium built in 1982, hosts both one day internationals and test matches. It is the largest stadium in the world by capacity, with a seating capacity of 132,000 spectators.[245] It hosted the 1987, 1996, 2011, and 2023 Cricket World Cups.[246] It is the home ground of the Gujarat cricket team, a first-class team, which competes in domestic tournaments. Ahmedabad has a second cricket stadium at the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation's Sports Club of Gujarat.[247] The final of 2023 Cricket World cup was held at the Narendra Modi Stadium.[248] Ahmedabad is also home to the IPL team Gujarat Titans, who won its first title in 2022 in front of its home crowd.[249]

Other popular sports include field hockey, badminton, tennis, squash and golf. Ahmedabad has nine golf courses.[250] Mithakhali Multi Sports Complex is being developed by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation to promote various indoor sports.[251] Ahmedabad has also hosted national level games for roller skating and table tennis.[252] Kart racing is gaining popularity in the city, with the introduction of a 380 metre long track based on Formula One design concepts.[253][254]

Sabarmati Marathon has been organized every year December–January since 2011; it has categories like a full and half-marathon, a 7 km dream run, a 5 km run for the visually disabled, and a 5 km wheelchair run.[255] In 2007, Ahmedabad hosted the 51st national level shooting games.[256] The 2016 Kabaddi World Cup was held in Ahmedabad at The Arena by Transtadia (a renovated Kankaria football ground). Geet Sethi, a five-time winner of the World Professional Billiards Championship and a recipient of India's highest sporting award, the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna, was raised in Ahmedabad.[257]

The Adani Ahmedabad Marathon has been organized by the Adani Group every year since 2017; it attracted 8,000 participants in its first edition and also hosted its first virtual marathon in 2020 in compliance with COVID-19 guidelines.[258]

2036 Olympics

[edit]Ahmedabad has been identified as a potential host city for the 2036 Summer Olympics. The Gujarat government has identified 33 sites in and around Ahmedabad for the development of infrastructure to support the Olympic bid.[259] The city's bid is also being shaped with international expertise, including Australian consultants.[260] A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) is being set up by the Gujarat government to manage Ahmedabad's bid for the games.[261] The fate of the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium is under consideration as part of the city's preparation for the Olympics.[262]

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Astrakhan, Russia[263]

Astrakhan, Russia[263] Columbus, United States (2008) [264]

Columbus, United States (2008) [264] Guangzhou, China (September 2014)[265]

Guangzhou, China (September 2014)[265] Jersey City, United States (1994) [266]

Jersey City, United States (1994) [266]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b PTI. "BJP corporator Pratibha Jain elected as mayor of Ahmedabad; Vadodara too gets new mayor". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 20 January 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Gujarat government transport 23 IAS officers; AMC GMC get new commissioners". DeshGujarat. 12 October 2022. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ "City police gets new M(a)alik". Archived from the original on 23 May 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "About Us". Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/42876/download/46544/CLASS_I.xlsx

- ^ Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation https://ahmedabadcity.gov.in/SP/AboutAhmedabad

- ^ "Gujarāt (India): State, Major Agglomerations & Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- ^ https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/india/ahmedabad

- ^ Kaushik, Himanshu; Parikh, Niyati (3 January 2019). "GJ-01 series registers 12% drop in one year". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "District Human Development Reports United Nations Development Programme". UNDP. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Distribution of Population, Decadal Growth Rate, Sex-Ratio and Population Density". 2011 census of India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ "Gujarat elections 2022: Seats with high literacy rates record low voting numbers". The Times of India. 8 December 2022. ISSN 0971-8257. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ |C40 Cities| https://www.c40.org/cities/ahmedabad/

- ^ India's most populated cities https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/cities/india Archived 3 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ahmedabad Population 2024". World Population Review. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "India: States and Major Agglomerations – Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Major Agglomerations of the World – Population Statistics and Maps". citypopulation.de. 1 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016.

- ^ "Ahmadabad & Gandhinagar a tale of twin cities". One India One People. 1 December 2015. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ a b Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (2006). "Profile of the City Ahmadabad" (PDF). Ahmadabad Municipal Corporation Ahmadabad, Urban Development Authority and CEPT University, Ahmadabad. Ahmadabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Ahmadabad joins ITES hot spots". The Times of India. 16 August 2002. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ Kotkin, Joel. "In pictures—The Next Decade's fastest growing cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ "Ahmedabad best city to live in, Pune close second". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ "Ahmedabad - C40 Cities". C40.org.

- ^ Tiwari, Anuj (22 October 2021). "Richest Cities Of India". India Times. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

The Manchester of East, Ahmedabad, is among the richest cities of India. The city ranks eighth on the list with an estimated GDP of $68 billion.

- ^ "Ahmedabad rated as third best city to live in, moves up by 20 spots in a year". www.timesnownews.com. 5 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Ahmedabad, India: World's Greatest Places 2022". Time. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Government releases list of 20 smart cities". The Times of India. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "600-year-old smart city gets World Heritage tag". The Times of India. 9 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ a b Michell & Shah 1988, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Bobbio 2015, p. 164.

- ^ Michell & Shah 1988, p. 18.

- ^ Turner, Jane (1996). The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 1. Grove. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-884446-00-9.

- ^ Michell, George; Snehal Shah; John Burton-Page; Mehta, Dinesh (28 July 2006). Ahmadabad. Marg Publications. pp. 17–19. ISBN 81-85026-03-3.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India Through the Ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 173.

- ^ Wink, André (1990). Indo-Islamic Society: 14th - 15th Centuries. Brill. p. 143. ISBN 978-90-04-13561-1. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

Zafar Khan Muzaffar, the first independent ruler of Gujarat was not a foreign muslim but a Khatri convert, of a low subdivision called Tank, originally from Southern Punjab.

- ^ Kapadia, Aparna (2018). In Praise of Kings: Rajputs, Sultans and Poets in Fifteenth-century Gujarat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-107-15331-8. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

Gujarati historian Sikandar does narrate the story of Muzaffar Shah's ancestors having once been Hindu "Tanks", a branch of Khatris who trace their dynasty from the solar god.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- ^ a b c More, Anuj (18 October 2010). "Baba Maneknath's kin keep alive 600-yr old tradition". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ This ambiguity is similar to the case of Tsar Peter the Great naming his new capital "Saint Petersburg", referring officially to Saint Peter but in fact also to himself.

- ^ a b c d e "History of Ahmedabad". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, egovamc.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (14 November 2010). "In Ahmedabad, history is still alive as tradition". dna. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "History". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Jilkad is anglicized name of the month Dhu al-Qi'dah, Hijri year not mentioned but derived from date converter

- ^ Desai, Anjali H., ed. (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9780978951702. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Flags changed at city's foundation by Manek Nath baba's descendants". The Times of India. TNN. 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Ruturaj Jadav and Mehul Jani (26 February 2010). "Multi-layered expansion". Ahmedabad Mirror. AM. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "02/26/2015: Divya Bhaskar e-Paper, ahmedabad, e-Paper, ahmedabad e Paper, e Newspaper ahmedabad, ahmedabad e Paper, ahmedabad ePaper". Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ^ Ajay, Lakshmi (27 February 2015). "Ahmedabad city turns 604". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ "Manek Burj's sorry state fails to move AMC". DNA. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Kuppuram, G (1988). India Through the Ages: History, Art, Culture, and Religion. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 739. ISBN 978-81-85067-08-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2004). The Mughal Throne. Orion Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7538-1758-2.

- ^ Sangwan, Satpal; Y. P. Abrol; Mithilesh K. Tiwari (2002). Land Use – Historical Perspectives: Focus on Indo-Gangetic Plains. Allied Publishers. p. 151. ISBN 978-81-7764-274-2. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Prakash, Om (2003). Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement. Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. pp. 282–284. ISBN 81-261-0938-6.

- ^ Kalia, Ravi (2004). "The Politics of Site". Gandhinagar: Building National Identity in Postcolonial India. Univ of South Carolina Press. pp. 30–59. ISBN 1-57003-544-X. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ Iain Borden; Murray Fraser; Barbara Penner (11 August 2014). Forty Ways to Think About Architecture: Architectural History and Theory Today. John Wiley & Sons. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-118-82261-6. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b A. Srivathsan (23 June 2006). "Manchester of India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2006.

- ^ Gilly, Thomas Albert; Gilinskiy, Yakov (8 December 2009). The Ethics of Terrorism: Innovative Approaches from an International Perspective (17 Lectures). Charles C Thomas Publisher. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-398-07867-6. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1962). Cities and Civilization. Popular Prakashan. p. 96.

- ^ Acyuta Yājñika; Suchitra Sheth (2005). The Shaping of Modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva, and Beyond. Penguin Books India. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-14-400038-8. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Political Science. FK Publications. 1978. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-89611-86-6. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Wolf, Jr., Charles. "Korea's Five year plan" (PDF). Ministry of Reconstruction of Korea. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Raje, Aparna Piramal (23 January 2013). "Ahmedabad: The perfect metropolis". mint. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "The case of Ahmedabad, India" (PDF). Case Studies: Global Human Settlements. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Shah, Ghanshyam (20 December 2007). "60 revolutions—Nav nirman movement". India Today. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Yagnik, Achyut (May 2002). "The pathology of Gujarat". New Delhi: Seminar Publications. Archived from the original on 22 March 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ Sinha, Anil. "Lessons learned from the Gujarat earthquake". WHO Regional Office for south-east Asia. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ "Safehouse of Horrors". Tehelka. 3 November 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ "CNN.com - Desolate life in India's refugee camps - May 15, 2002". edition.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "17 bomb blasts rock Ahmedabad, 15 dead". CNN-IBN. 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ^ "India blasts toll up to 37". CNN. 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2008.

- ^ Langa, Mahesh (23 February 2020). "Ahmedabad glitters to welcome Donald Trump". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Chinese President Xi Jinping arrives in Ahmedabad". The Economic Times. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Justin Trudeau visits IIM A, says empowering women is the smart thing to do". Ahmedabad Mirror. 19 February 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Ahmedabad Population 2023". Population Census. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b "City Census 2011". Population Census. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Census: Population: City: Ahmedabad". CEIC Data. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Urban Agglomerations Census 2011". Population Census. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ "Census to be delayed again, deadline for freezing administrative boundaries pushed to January 1, 2024". The Indian Express. 3 July 2023. Archived from the original on 29 July 2024. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Bhatkal, Tanvi, William Avis, and Susan Nicolai. "A Cautionary Tale of Progress in Ahmedabad", n.d., 48.

- ^ a b World Bank. 2007. The Slum Networking Project in Ahmedabad: partnering for change (English) Archived 29 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Water and Sanitation Program case study. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/353971468259772248/The-Slum-Networking-Project-in-Ahmedabad-partnering-for-change

- ^ SEWA Academy (2002) Parivartan and its impact: A Partnership Programme of Infrastructure Development in Slums of Ahmedabad City. SEWA Monograph. Ahmedabad: Self Employed Women's Association.

- ^ "Dubai International Award for Best Practices Winners | Ahmedabad Slum Networking Programme". mirror.unhabitat.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Mount Carmel Cathedral". Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018. GCatholic

- ^ "Our Parish". St. Xavier’s Parish, Ahmedabad. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "High ageing rate, health problems worry Parsi community". The Times of India. 22 October 2001. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ "Jews of Ahmedabad, India, welcome Torah scroll". Archived 15 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine Jewish Journal. 13 September 2012. 13 September 2012.

- ^ Katz, Nathan; Ellen S. Goldberg. "The Last Jews in India and Burma". Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2006.

- ^ Baines, Jervoise Athelstane; India Census Commissioner (28 January 1891). "Census of India, 1891. General tables for British provinces and feudatory states". JSTOR saoa.crl.25318666. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Dracup, A.H. (1942). Census of India, 1941. Vol. III: Bombay Tables. Government of India Press. pp. 56–57.

- ^ "Expansion of Municipal Corporations". The Times of India. 19 June 2020. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Municipalities have extension in Gujarat". Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "AMC Expansion". 8 September 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Amdavad city". Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Gujarat State Gazetteers. Directorate of Govt, Print., Stationery and Publications, Gujarat State. 1984. p. 46.

- ^ "Performance of buildings during the 2001 Bhuj earthquake" (PDF). Jag Mohan Humar, David Lau, and Jean-Robert Pierre. The Canadian Association for Earthquake Engineering. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ "Historic city of Ahmadabad - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Reader in Urban Sociology. Orient Blackswan. 1991. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-0-86311-152-5. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ "Residential Cluster, Ahmedabad: Housing based on the traditional Pols" (PDF). arc.ulaval.ca/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Patel, Bholabhai (26 February 2011). "અમદાવાદની પોળ સંસ્કૃતિની એક મર્મસ્પર્શી ઝલક" (in Gujarati). Divya Bhaskar. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Tentative Lists". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Dave, Jitendra (28 August 2009). "Ahmedabad heritage set to conquer Spain". Daily News and Analysis. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Vaarso". Ahmedabad Mirror. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Urban Structure and Growth". The Ahmedabad Chronicle: Imprints of a Millennium. Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design. 2002. p. 83.

- ^ "Sabarmati River Front Time line". Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Ahmedabad records hottest day in century as mercury hits 48 degrees Celcius". Indian Express. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Station: Ahmedabad Climatological Table 1991–2020" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1991–2020. India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ "Ever recorded Maximum and minimum temperatures up to 2010" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Climatological Information - Ahmedabad (42647)". India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India". Time and Date. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Climate Normals 1971–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "VAAH Data for May 18, 2016". IEM. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ "Normals Data: Ahmedabad - India Latitude: 23.07°N Longitude: 72.63°E Height: 55 (m)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "Climate and monthly weather forecast Ahmedabad, India". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Climatological Tables 1991-2020" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Chitre, Mandar; Halliday, Adam (3 May 2012). "Weather: Researchers fear 'May 2010 heat wave' may return to city". Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Heat Action Plan – Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation" (PDF). Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Feature: Ahmedabad, India launches heat wave preparation and warning system Archived 4 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Climate & Development Knowledge Network. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Addressing heat-related risks in urban India: Ahmedabad's Heat Action Plan Archived 12 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Dr Tejas Shah, Dr Dileep Mavalankar, Dr Gulrez Shah Azhar, Anjali Jaiswal and Meredith Connolly, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, Indian Institute of Public Health-Gandhinagar and the Natural Resources Defense Council, 2014

- ^ "Swachh Vayu Sarvekshan 2024" (PDF). prana.cpcb.gov.in. 7 September 2024.

- ^ a b B.R. Kishore; Shiv Sharma (2008). India – A Travel Guide. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 491. ISBN 978-81-284-0067-4. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (15 November 2009). "Calico dome: Crumbling crown of architecture". Daily News and Analysis. India. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Shastri, Parth (16 October 2011). "Calico Dome: The icon of its time". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Doshi, Balkrishna V.; Tsuboi, Yoshikatsu; Raj, Mahendra (1967). "Tagore hall". Arts Asiatiques. 60. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Gans, Deborah (2006). The Le Corbusier guide. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 211–. ISBN 978-1-56898-539-8. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Gargiani, Roberto; Rosellini, Anna (25 November 2011). Le Corbusier: Beton Brut and Ineffable Space (1940–1965): Surface Materials and Psychophysiology of Vision. EPFL Press. pp. 417–. ISBN 978-0-415-68171-1. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Christopher Charles Benninger Architects". Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "He was a teacher and an institution". The Times of India. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Law Garden Night Market". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Endangered species Identified for breeding and their species coordinator". Central Zoo Authority India. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ Ward, Philip (1998). Gujarat-Daman-Diu. Orient Longman Limited. ISBN 9788125013839. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Pandya, Yatin (2 April 2012). "Reminiscing the Kankaria Lake of yore". DNA India. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Jadav, Ruturaj (14 April 2010). "City of lakes-With 34 new lakes under development, Ahmedabad is set to pose a challenge to Udaipur". Ahmedabad Mirror. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Vastapur lake travel guide". Trodly. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ It's a Jungle Out tHere [sic]. The Indian Express, 18 August 2013

- ^ "Chandola Lake". ahmedabad.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012.

- ^ "Get ready to pay entry fee at Naroda Lake". dna. 11 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ "VCCCI". vccci.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ Mahadevia, Darshin (2008). Inside the Transforming Urban Asia: Processes, Policies and Public Actions (1. publ. ed.). New Delhi: Concept. p. 650. ISBN 978-81-8069-574-2. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Ahmedabad: Air purifiers to be installed near Pirana dumping site for traffic police". dna. 8 February 2019. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Bijal Patel appointed city Mayor". Ahmedabad Mirror. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Nair, Ajesh. "Annual Survey of India's City-Systems" (PDF). janaagraha.org. Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Ahmedabad registers two accidents per hour and Gujarat 18: EMRI 108". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ "CCRS". www.amccrs.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Delimitation order announced: Ahmedabad to have 48 wards". The Indian Express. 30 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "City Information". aai.aero/. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Saikia new Ahmedabad police chief". The Indian Express. 20 October 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ Dasgupta, Manas (25 September 2008). "Civil Hospital planned as world's biggest hospital". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Group Companies—The Ahmedabad Electricity Company Limited". Torrent Group. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ Vedavalli, Rangaswamy (13 March 2007). Energy for Development: Twenty-first Century Challenges of Reform and Liberalization in Developing Countries. Anthem Press. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-1-84331-223-9. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Shah, K. (2015). "Documentation and Cultural Heritage Inventories – Case of the Historic City of Ahmadabad" (PDF). ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. II5: 271. Bibcode:2015ISPAn.II5..271S. doi:10.5194/isprsannals-II-5-W3-271-2015. ISSN 2196-6346. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Lacklustre Uttarayan for kite sellers due to demand slump". The Indian Express. 13 January 2023. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Festive fervour high as people gear up for Navratri celebrations". The Indian Express. 20 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ O'Brien, Charmaine (2013). The Penguin Food Guide to India. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-93-5118-575-8. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Dalal, Tarla (2003). The Complete Gujarati Cookbook. Sanjay & Co. p. 4. ISBN 81-86469-45-1. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Naomi Canton (17 August 2017). "We're beneficiaries of reverse colonialism: Boris". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Food – IIMA". iimahd.ernet.in. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "Made for India: Succeeding in a Market Where One Size Won't Fit All". India Knowledge@Wharton. The Wharton School. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "KFC in Ahmedabad". Burrp.com Network 18. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Nair, Avinash (17 October 2011). "Kentucky Friend [sic] Chicken changes dress code for vegeterian [sic] Gujarat". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Hum dono hai alag alag" (PDF). press release. McDonald's India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Mcdonald's in Ahmedabad". Burrp.com Network 18. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Ahmedabad Food". Outlook Traveller. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Anjali H. Desai (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-9789517-0-2. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.