Assassination of Pim Fortuyn

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Assassination of Pim Fortuyn | |

|---|---|

The car park where Fortuyn was assassinated (directly behind the red car) | |

| Location | Hilversum, Netherlands |

| Date | 6 May 2002 18:06 (CEST) |

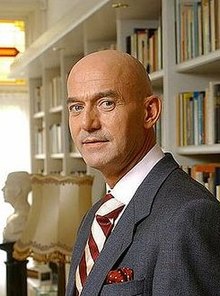

| Target | Pim Fortuyn |

Attack type | Assassination |

| Weapons | Star M-43 Firestar (9×19mm) |

| Deaths | 1 (Fortuyn) |

| Perpetrator | Volkert van der Graaf |

| Motive | Left-wing extremism |

Pim Fortuyn, a Dutch politician, was assassinated by Volkert van der Graaf in Hilversum, North Holland on 6 May 2002, nine days before the general election of 2002, in which he was leading the Pim Fortuyn List (LPF).[1][2]

On a few occasions, Fortuyn had expressed his fear of being murdered: after being pied at the official release of his book De puinhopen van acht jaar Paars,[3] as well as, most notably, on the talk show Jensen! on 22 March 2002.[4] In court at his trial, Van der Graaf, an environmental and animal rights activist,[5][6] said he murdered Fortuyn to stop him from exploiting Muslims as "scapegoats" and targeting "the weak members of society" in seeking political power.[7][8][9] Van der Graaf was sentenced to eighteen years in prison. The sentence was upheld after he appealed. He was released on parole in 2014 after completing two-thirds of his sentence and has since lived in Apeldoorn, Gelderland.

Attack and death

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Fortuyn was 54 years old when he was shot dead by 32-year-old Volkert van der Graaf in a car park outside a radio studio where Fortuyn had just given an interview to Ruud de Wild at 3FM. The attacker was pursued by Fortuyn's driver, Hans Smolders; he was arrested shortly afterwards while still in possession of the handgun used to assassinate Fortuyn.[10][11]

Van der Graaf was arrested near the scene of the crime after a pursuit by witnesses. Details of the suspect were always officially reported as "Volkert van der G." in accordance with unwritten Dutch privacy practice, but his full name was readily available on the internet. His home and work addresses were soon circulated on websites used by Fortuyn's supporters. Angry supporters gathered in several cities, so several people related to Van der Graaf went into hiding. His girlfriend and their daughter left their house on the evening of the murder.

The details of the murder emerged later; the accounts of the investigators and Van der Graaf were consistent. He had planned the attack using information obtained from the Internet; printouts of a map of the scene of the crime and schedules of Fortuyn's appearances were found in his car. In two boxes of cartridges found at his home, seven cartridges were missing, the exact number loaded in his gun. The attack has been described as the work of a single person, an amateur shooter who used a relatively simple plan and did not prepare a good escape route.

Van der Graaf purchased his weapon and ammunition illegally; a semi-automatic Star Firestar M43 pistol in a café in Ede and 9mm cartridges in The Hague. After the murder of Fortuyn, the gun was linked to a suspect in the robbery of a jeweller in Emmen through DNA material found on the weapon. On the day of the murder, he attended work in the morning, taking with him a backpack containing the gun, a pair of latex gloves, a baseball cap and a pair of dark glasses. At the end of the morning, he said he was taking the afternoon off on account of the beautiful weather. He drove towards Hilversum, knowing that Fortuyn was due to be interviewed in the radio studio of 3FM in the Media Park. During the trip he stopped several times, among other things to purchase a razor to remove his stubble, which together with the cap and glasses would disguise his appearance, while the gloves would avoid leaving fingerprints. The razor did not work.

He had never visited the Media Park, relying on a map and a couple of photographs to find his way into the park on foot and to the building where Fortuyn's interview was held. Recognising Fortuyn's car in the car park, he hid in some nearby bushes, burying the gun which was in a plastic bag in a shallow trough in case he was discovered. He could hear fragments of Fortuyn's interview from a speaker on the outside of the building. He waited there for about two hours.

Fortuyn emerged from the building in the company of several others. Van der Graaf walked towards Fortuyn, passed by him, then turned and opened fire. He said that he aimed for the back to avoid Fortuyn's ducking away, or that a bullet would mistakenly hit somebody else. He held the gun in both hands, with the plastic bag around it. Less than 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) from Fortuyn, he hit him in the back and head five times. He fired a sixth shot that missed.

Running away, Van der Graaf was chased by Hans Smolders, Fortuyn's chauffeur. Two employees from a different building joined in. During the chase, Van der Graaf threatened them by raising the gun in his jacket pocket toward them. They ran from the grounds of the Media Park onto a public road, where Van der Graaf pointed the pistol at arm's length at Smolders. He had been reporting their position to the police by mobile phone. Reaching a petrol station, Van der Graaf gave up when police pointed their pistols at him.[12]

Response

[edit]

The assassination shocked many in the Netherlands and exposed cultural clashes within the country. Riots broke out on the Binnenhof on the evening following the killing.[13] Politicians from all political parties suspended campaigning, but the elections were not postponed.[14] Under Dutch law, it was not possible to modify the ballots, so Fortuyn became a posthumous candidate. The Pim Fortuyn List (LPF) went on to make an unprecedented debut in the House of Representatives, winning 26 seats (17% of the 150 seats in the house). This success was short-lived. In the elections the following year, Pim Fortuyn seats dropped to eight. After the 2006 elections, the party had no seats in the House of Representatives.

On 15 April 2003, Volkert van der Graaf was convicted of assassinating Fortuyn and sentenced to 18 years in prison.[15] He was released on parole in May 2014 after serving two-thirds of his sentence, the standard procedure under the Dutch penal system.[16]

Pim Fortuyn is credited with changing the Dutch political landscape and culture with his ideology, which came to be known as Fortuynism. The 2002 elections were marked by large losses for the liberal People's Party for Freedom and Democracy and the social democratic Labour Party. Both parties replaced their leaders shortly after the election. The Pim Fortuyn List and Christian Democratic Appeal made significant gains. There have been others[who?] that speculate Fortuyn's perceived martyrdom may have played in favour of the Pim Fortuyn List.[17]

The coalition cabinet which formed after the election of the Christian Democratic Appeal, Pim Fortuyn List and People's Party for Freedom and Democracy fell after three months, due to conflicts between LPF members. In the following elections, the Pim Fortuyn List returned eight seats in the House of Representatives and did not form part of the new government. However, political commentators[who?] speculated[vague] that there was still a sizable number of discontented voters who might have voted for a non-traditional party, if a viable alternative was available. In recent times, the right-wing Party for Freedom, which has a strong stance on immigration and integration, won nine seats in 2006 and 24 in 2010.

In a 2004 television show election, Fortuyn was chosen as De Grootste Nederlander ("Greatest Dutchman of All Time"), followed by William the Silent, the leader of the war for independence that established the precursor to the present-day Netherlands. The validity of this election, where votes were cast online and over the phone, was questioned and dismissed as being easily influenced by Fortuyn's supporters. The murder of film director Theo van Gogh for comments critical of Islam had occurred a few days before the election and many votes for Fortuyn were attributed to this event.[citation needed] It later turned out that William the Silent had received more votes, many of which were not counted before Fortuyn was declared the winner, due to technical problems.[18]

After Fortuyn's death, the Netherlands' right-wing politicians, including former Minister for Integration and Immigration Rita Verdonk and Geert Wilders, increased in profile and prominence.[19] Further, various conspiracy theories arose after Pim Fortuyn's murder that deeply affected Dutch politics and society.[20]

The pistol used in the shooting has been donated to the Rijksmuseum, although it is not expected to be exhibited for "several decades".[21]

References

[edit]- ^ (in Dutch) Kok: Fortuyn had verkiezingen gewonnen

- ^ (in Dutch) Kok: Fortuyn had beslist gewonnen

- ^ "De Journalist". Villamedia.nl. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ "Fortuyn te gast bij Jensen". YouTube. 15 September 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ "Profile: Fortuyn killer". BBC News. 15 April 2003. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ Marlise Simons, "Dutch Suspect In Slaying Championed Animal Rights", The New York Times, 9 May 2002, Retrieved 20 April 2011

- ^ Fortuyn killed 'to protect Muslims', The Daily Telegraph, 28 March 2003:

- [van der Graaf] said his goal was to stop Mr. Fortuyn exploiting Muslims as "scapegoats" and targeting "the weak parts of society to score points" to try to gain political power.

- ^ Fortuyn killer 'acted for Muslims', CNN, 27 March 2003:

- Van der Graaf, 33, said during his first court appearance in Amsterdam on Thursday that Fortuyn was using "the weakest parts of society to score points" and gain political power.

- ^ "Jihad Vegan". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Dr Janet Parker 20 June 2005, New Criminologist - ^ Conway, Isobel (7 May 2002). "Dutch far-right leader shot dead". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ (in Dutch) Moord op Pim Fortuyn YouTube, original RTL Nieuws

- ^ A Democracy In Shock, YouTube, documentary about the murder of Pim Fortuyn

- ^ "Boetes na rellen Pim Fortuyn" [Fines after Pim Fortuyn riots]. RTV Rijnmond. 16 May 2002.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (8 May 2002). "Elections to Proceed in the Netherlands, Despite Killing". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (16 April 2003). "'Light' sentence enrages Fortuyn's followers". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ "Pim Fortuyn: Politician's Killer Is Freed Early". Sky News. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (7 May 2002). "Rightist in Netherlands Is Slain, and the Nation Is Stunned". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ (in Dutch) Pim Fortuyn: Erfenis Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Dutch) Verdonk en Wilders strijden om nalatenschap Pim Fortuyn Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jelle van Buuren: Holland's Own Kennedy Affair. Conspiracy Theories on the Murder of Pim Fortuyn. Historical Social Research Vol. 38, 1 (2013), pp. 257–85.

- ^ Janene Pieters (21 March 2017). "Populist politician's murder weapon in Rijksmuseum collection".