NASA Astronaut Group 4

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The Scientists | |

|---|---|

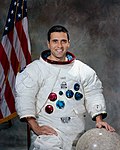

Group 4 astronauts. Back row, left to right: Garriott, Gibson. Front row, left to right: Michel, Schmitt, Kerwin. Not pictured: Graveline | |

| Year selected | 1965 |

| Number selected | 6 |

NASA Astronaut Group 4 (nicknamed the "The Scientists") was a group of six astronauts selected by NASA in June 1965. While the astronauts of the first two groups were required to have an undergraduate degree or the professional equivalent in engineering or the sciences (with several holding advanced degrees), they were chosen for their experience as test pilots. Test pilot experience was waived as a requirement for the third group, and military jet fighter aircraft experience could be substituted. Group 4 was the first chosen on the basis of research and academic experience (an M.D. or Ph.D. in the natural sciences or engineering was a prerequisite for selection), with NASA providing pilot training as necessary. Initial screening of applicants was conducted by the National Academy of Sciences.

Of the six ultimately chosen, four had military experience. Schmitt, a geologist, walked on the Moon, while Garriott, Gibson and Kerwin all flew to Skylab. Garriott also flew on the Space Shuttle. Graveline and Michel left NASA without flying in space.

Background

[edit]The launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, started a Cold War technological and ideological competition with the United States known as the Space Race. The demonstration of American technological inferiority came as a profound shock to the American public.[1] In response to the Sputnik crisis, although he did not see Sputnik as a grave threat,[2] the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower, created a new civilian agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), to oversee an American space program.[3] In doing so, he sought to emphasise the scientific nature of the American space program and downplay its military aspects.[2]

In response to pressure from Congress to match and surpass Soviet achievements in space,[4] NASA created an American crewed spaceflight project called Project Mercury.[5] Project Mercury attracted criticism from the scientific community, who preferred a more methodical approach to space science.[4] With the replacement of Eisenhower by John F. Kennedy in 1961, a President's Science Advisory Committee panel headed by Donald Hornig was charged with reporting on Project Mercury. NASA feared that space exploration would be turned over to the Department of Defense, but found support for an expanded scientific space program from the Space Science Board of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS).[6] At its meeting on February 10–11, 1961, the Space Science Board adopted a formal resolution to support crewed space exploration.[7]

Confidence that the United States was catching up with the Soviet Union was shattered on April 12, 1961, when the Soviet Union launched Vostok 1, and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth. In response, Kennedy announced a far more ambitious goal on May 25, 1961: to put a man on the Moon by the end of the decade.[8] This already had a name: Project Apollo.[9] Over the next few years, space science would constitute up to 20 percent of NASA's budget, but it would be dwarfed by spending on Project Apollo.[10] NASA asked the Space Board to conduct a review of the space program, and this was done at the State University of Iowa between June 17 and July 31, 1962. The study recommended that scientists be included in the astronaut program, and that a scientist be included in the first mission to the Moon.[11]

Robert B. Voas, NASA's Assistant Director for Human Factors, drew up a proposal for the selection and training of scientists as astronauts, which he submitted in draft form on May 6, 1963. He pointed out the value in getting the support of the scientific community at a time when NASA's budget faced opposition in Congress. NASA officially announced an intention to recruit scientists as astronauts on June 5, 1963.[12] On October 1, 1964, NASA announced that it was recruiting scientist astronauts as well as another intake of pilot astronauts.[13]

Selection

[edit]Key selection criteria were that candidates:

- Be a United States citizen;

- Born on or after August 1, 1930;

- 6 feet 0 inches (1.83 m) or less in height;

- With a doctorate in the natural sciences, medicine or engineering, or the equivalent.[14]

The height requirement was firm, an artifact of the size of the Apollo spacecraft. Candidates had to have copies of their academic transcripts from each university they had attended, along with Educational Testing Service scores and medical history were sent directly to the Astronaut Selection Board of the NAS by December 31, 1964, along with medical examination results. In addition, they could send supporting materials, which might include papers they had written, research they had conducted, or simply their thoughts about space science. They also had to be able to pass a Class I Military Flight Status Physical. This required 20/20 uncorrected vision. The helmets astronauts wore could not accommodate glasses, and contact lenses were considered to be unsuitable in space.[14]

A total of 1,351 applications were received by the deadline. About 200 of these were rejected for failing to meet the basic age, citizenship, height or vision criteria. The names of 400 applicants (four of whom were women) were forwarded to NAS to review their academic qualifications.[14] The NAS selection board consisted of Allan H. Brown, Loren D. Carlson, Frederick L. Ferris, Thomas Gold, H. Keffer, Clifford Morgan, Eugene Shoemaker, Robert Speed and Aaron Waters.[15] The NAS boards reduced the number of candidates to just fifteen. On May 2, 1965, they were sent to the United States Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine at Brooks Air Force Base, near San Antonio, Texas, for medical examinations.[16] The final step, on May 12, 1965, was an interview by the NASA selection panel, which consisted of Charles A. Berry, John F. Clark, Maxime Faget, Warren J. North and Mercury Seven astronauts Alan B. Shepard and Donald K. Slayton.[15] The names of the six successful candidates were publicly announced at a press conference on June 29, 1965.[17] They were the first astronauts chosen on the basis of research and academic experience.[18]

Group members

[edit]| Image | Name | Born | Died | Career | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owen K. Garriott | Enid, Oklahoma, November 22, 1930 | April 15, 2019 | Garriott received a B.S. in electrical engineering from the University of Oklahoma in 1953. From 1953 to 1956 he served with the U.S. Navy as an electronics officer. He then entered Stanford University and earned an M.S. in 1957 and a Ph.D in 1960 in electrical engineering. He became an assistant professor, and then an associate professor in the Electrical Engineering department there. His first space flight was in July 1973 as Science Pilot on the Skylab 3 mission, the second crew of the Skylab space station. He was Deputy, Acting and Director of Science and Applications at the Johnson Space Center from 1974 to 1975 and 1976 to 1978. As such he was responsible for all research in the physical sciences at the Johnson Space Center. From 1984 to 1986, he was Project Scientist in the Space Station Project Office. He flew in space a second time on STS-9 Columbia in November 1983 as a mission specialist on the Spacelab mission. He retired from NASA in June 1986. | [19][20] |

| Edward G. Gibson | Buffalo, New York, November 8, 1936 | Gibson received a B.S. in engineering from the University of Rochester in 1959, an M.S. in engineering from the California Institute of Technology in 1960, and a Ph.D. in engineering with a minor in physics from the California Institute of Technology in 1964. He was on the support crew of the Apollo 12 lunar landing mission, and flew in space on the Skylab 4 mission in November 1973 to February 1974 as Science Pilot in the third crew of the Skylab space station. He left NASA in December 1974. | [21] | |

| Duane E. Graveline | Newport, Vermont, March 2, 1931 | September 5, 2016 | Graveline received his B.S. degree from the University of Vermont in 1951 and his M.D. from the University of Vermont College of Medicine in 1955. He joined the U.S. Air Force Medical Service, and was an intern at Walter Reed Army Hospital from July 1955 to June 1956. He attended the primary course in Aviation Medicine at Randolph Air Force Base in Texas, and was assigned to Kelly Air Force Base in Texas as Chief of the Aviation Medicine Service there. He was granted the U.S. Air Force aeronautical rating of flight surgeon in February 1957, and received a master's degree in public health from the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. He resigned from NASA in August 1965 before being assigned to a crew after his first wife filed for a divorce. He returned to Vermont, where he served as a flight surgeon with the Vermont Army National Guard, and practiced medicine until the state revoked his medical license in 1994. | [22][23][24] |

| Joseph P. Kerwin | Oak Park, Illinois, February 19, 1932 | Kerwin received his B.A. degree in philosophy from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1953, and his M.D. from Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, Illinois, in 1957. He completed his internship at the District of Columbia General Hospital in Washington, D.C., and attended the U.S. Navy School of Aviation Medicine on Pensacola, Florida, where he qualified as a naval flight surgeon in December 1958. He earned his United States Naval Aviator wings at Beeville, Texas, in 1962. He flew in space on Skylab 2 in May and June 1973 as Science Pilot in the first crew of the Skylab space station. He was NASA's senior science representative in Australia from 1982 to 1983, and Director of Space and Life Sciences at the Johnson Space Center from 1984 to 1987, when he resigned from NASA to join Lockheed, where he was involved in the development of hardware for the Space Station Freedom and later the International Space Station. | [25] | |

| F. Curtis Michel | La Crosse, Wisconsin, June 5, 1934 | February 26, 2015 | Michel received his B.S. with honors in Physics in 1955 and Ph.D. Physics in 1962 from the California Institute of Technology. He was a junior engineer with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company's Guided Missile Division until he joined the U.S. Air Force in 1955. An AFROTC graduate, he received flight training at Marana Air Base in Arizona, and at Laredo Air Force Base and Perrin Air Force Base in Texas, and flew F-86D Interceptors in the United States and Europe. In 1958 he became a research fellow at the California Institute of Technology. He joined the faculty of Rice University in Houston, Texas on 1963. He resigned from NASA in September 1969 before being assigned to a crew, and returned to Rice University, where he became the Andrew Hays Buchanan Professor of Astrophysics. He was a Guggenheim Fellow in 1979, and was an Alexander von Humboldt Foundation award recipient in 1982. | [26] |

| Harrison H. Schmitt | Santa Rita, New Mexico, July 3, 1935 | Schmitt received his B.S. from the California Institute of Technology in 1957, and his Ph.D. in geology from Harvard University in 1964. He worked at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Center in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he was in charge of developing lunar field geological methods. He participated in photographic and telescopic mapping of the Moon, and was among USGS astrogeologists who instructed NASA astronauts during their geological field trips during astronaut training. He was the backup lunar module pilot on Apollo 15, and the prime lunar module on Apollo 17, the last crewed lunar landing, in December 1972. As such, he became the twelfth person to walk on the Moon. He resigned from NASA in August 1975 to run for the United States Senate in his home state of New Mexico. He was elected on November 2, 1976, and served one term. He then became an adjunct professor of engineering physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. | [27] |

Training

[edit]Two of the six were qualified pilots: Michel with the Air Force, and Kerwin with the Navy. They were given jobs related to space suits and Apollo experiments, respectively, while the rest were sent to Williams Air Force Base in Arizona for 55 weeks of pilot training.[28] Graveline resigned on August 18, 1965, after his first wife, Carole Jane née Tollerton, filed for divorce, in which she accused him of "violent and ungovernable outbursts of temper."[23] To avoid a scandal, and to send a message to other astronauts, NASA demanded his resignation.[29] Apart from Michel, who worked at nearby Rice University, they found that they were unable to continue their previous research.[30] When the pilot training was complete, all joined Alan Bean's Apollo Applications Branch.[31]

Along with the nineteen pilot astronauts of NASA Astronaut Group 5, the group commenced astronaut training. Training was conducted on Monday to Wednesday, with Thursday and Friday for field trips. They were given classroom instruction in astronomy (154 hours), aerodynamics (8 hours), rocket propulsion (8 hours), communications (10 hours), space medicine (17 hours), meteorology (4 hours), upper atmospheric physics (12 hours), navigation (34 hours), orbital mechanics (23 hours), computers (8 hours) and geology (112 hours). The training in geology included field trips to the Grand Canyon and the Meteor Crater in Arizona, Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico, Horse Lava Tube System in Bend, Oregon, and the ash flow in the Marathon Uplift in Texas, and other locations, including Alaska and Hawaii. There was also jungle survival training for the scientists in Panama, and desert survival training around Reno, Nevada. Water survival training was conducted at Naval Air Station Pensacola using the Dilbert Dunker. Some 30 hours of briefings were conducted on the Apollo spacecraft, and twelve on the lunar module.[32]

Operations

[edit]The scientists had various assignments. Schmitt, the only geologist in the group, spent most of his time on lunar landing site selection.[33] By 1967, it looked as if many fewer missions would be flown than originally planned, and the astronauts were risking their careers. Provision was made to allow the pilot astronauts to keep their pilot skills honed, but there was no such concession for the scientists.[34] Gibson became the first of the six scientists to be named to a crew when he was selected as a member of the support crew for Apollo 12 in April 1969,[35] but the announcement of prime and backups crews for Apollo 13 and Apollo 14 in August 1969 was the last straw for many. The prime and backup crews included eight members of the 1966 group of pilots, and Apollo 14 would be commanded by Mercury Seven astronaut Alan Shepard.[36] Michel resigned to return to teaching at Rice in September,[26] and there were resignations by NASA scientists Donald U. Wise, Elbert A. King Jr, Wilmot N. Hess and Eugene Shoemaker. All had their reasons for leaving, but all were highly critical of NASA. The calls for more participation by scientists did not go unheeded, and NASA Deputy Administrator George Mueller wrote to the director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), Robert R. Gilruth, in September 1969, and asked him to give the matter his personal attention.[37]

The MSC took steps to improve relations with the scientific community.[38] On March 26, 1970, Slayton announced that Schmitt would be backup lunar module pilot of Apollo 15; Richard F. Gordon, the command module pilot of Apollo 12, was named as backup commander, and Vance Brand as command module pilot. Under the prevailing rotation system, this set Schmitt up to walk on the Moon on Apollo 18. However, in September 1970, two more Apollo missions were cancelled; Apollo 17 would be the last Apollo mission to the Moon. Once again, frustration boiled over. Associate Administrator Homer E. Newell Jr. spoke with the scientist astronauts, and took their case to NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher. Newell recommended that a scientist astronaut be assigned to the next Moon mission, and that two be assigned to each Skylab mission.[39] Although Slayton insisted on two trained pilot astronauts for each Skylab mission,[40] on August 13, 1971, Schmitt was named as part of the prime crew of Apollo 17. He would become the last man to step onto the lunar surface.[41] The remaining three flew on Skylab missions, but only one per mission, as the "science pilot".[42]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 28–29, 37.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 56.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 82.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 58.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 325.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 67.

- ^ Burgess 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979, p. 15.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 63.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 68.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 86.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, p. 38.

- ^ "Scientist-Astronauts Join NASA Space Program" (PDF). NASA Roundup. Vol. 4, no. 19. July 9, 1965. pp. 1–2. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 54.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Owen K. Garriott". NASA. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Skylab and Space Shuttle Astronaut Owen Garriott Dies at 88". NASA. April 15, 2019. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Edward G. Gibson". NASA. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Duane Edgar Graveline". NASA. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Schwartz, John (September 17, 2016). "Duane Graveline, Doctor Who Was Forced Out as an Astronaut, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, p. 86.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Joseph P. Kerwin 4/87". NASA. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Astronaut bio – F. Curtis Michel" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2016.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio: Harrison Schmitt". NASA. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016.

- ^ Compton 1989, p. 67.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Compton 1989, p. 69.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 101–111.

- ^ Compton 1989, p. 135.

- ^ Compton 1989, p. 136.

- ^ Compton 1989, p. 164.

- ^ Compton 1989, p. 168.

- ^ Compton 1989, pp. 168–171.

- ^ Compton 1989, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Compton 1989, pp. 219–221.

- ^ Elder 1998, p. 222.

- ^ Compton 1989, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Shayler & Burgess 2007, pp. 253–257.

References

[edit]- Atkinson, Joseph D.; Shafritz, Jay M. (1985). The Real Stuff: A History of NASA's Astronaut Recruitment Program. Praeger special studies. New York, NY: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-005187-6. OCLC 12052375.

- Brooks, Courtney G.; Grimwood, James M.; Swenson, Loyd S. Jr. (1979). Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. The NASA History Series. Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA. ISBN 978-0-486-46756-6. LCCN 79001042. OCLC 4664449. SP-4205. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Burgess, Colin (2013). Moon Bound: Choosing and Preparing NASA's Lunar Astronauts. Springer-Praxis books in space exploration. New York, NY; London, England: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-3854-0. OCLC 905162781.

- Compton, William D. (1989). Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1045558568. SP-4214. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Elder, Donald C. (1998). "The Human Touch: The History of the Skylab Program". In Mack, Pamela E. (ed.). From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners (PDF). The NASA History Series. Washington, DC: NASA. pp. 213–234. ISBN 9780160496400. SP-4219. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- Shayler, David J.; Burgess, Colin (2007). NASA's Scientist Astronauts. Praxis Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-21897-7. OCLC 1058309996.

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. New York, NY: Forge. ISBN 978-0-312-85503-1. OCLC 937566894.

- Swenson, Loyd S. Jr.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1966). This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury (PDF). The NASA History Series. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 569889. NASA SP-4201.