Chaptalization

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Chaptalization is the process of adding sugar to unfermented grape must in order to increase the alcohol content after fermentation. The technique is named after its developer, the French chemist Jean-Antoine-Claude Chaptal.[1] This process is not intended to make the wine sweeter, but rather to provide more sugar for the yeast to ferment into alcohol.[1]

Chaptalization has generated controversy and discontent in the French wine industry due to advantages that the process is perceived to give producers in poor-climate areas. In response to violent demonstrations by protesters in 1907, the French government began regulating the amount of sugar that can be added to wine.

Chaptalization is sometimes referred to as enrichment, for example in the European Union wine regulations specifying the legality of the practice within EU.[2]

The legality of chaptalization varies by country, region, and even wine type. In general, it is legal in regions that produce grapes with low sugar content, such as the northern regions of France, Germany, and the United States. Chaptalization is, however, prohibited in Argentina, Australia, California, Italy, Portugal, Spain and South Africa. Germany prohibits the practice for making Prädikatswein.

History

[edit]

The technique of adding sugar to grape must has been part of the process of winemaking since the Romans added honey as a sweetening agent. While not realizing the chemical components, Roman winemakers were able to identify the benefits of added sense of body or mouthfeel.[3]

While the process has long been associated with French wine, the first recorded mention of adding sugar to must in French literature was the 1765 edition of L'Encyclopedie, which advocated the use of sugar for sweetening wine over the previously accepted practice of using lead acetate. In 1777, the French chemist Pierre Macquer discovered that the actual chemical benefit of adding sugar to must was an increase in alcohol to balance the high acidity of underripe grapes rather than any perceived increase in sweetness. In 1801, while in the services of Napoleon, Jean-Antoine-Claude Chaptal began advocating the technique as a means of strengthening and preserving wine.[4]

In the 1840s, the German wine industry was hard hit by severe weather that created considerable difficulty for harvesting ripened grapes in this cool region. A chemist named Ludwig Gall suggested Chaptal's method of adding sugar to the must to help wine makers compensate for the effects of detrimental weather. This process of Verbesserung (improvement) helped sustain wine production in the Mosel region during this difficult period.[5]

At the turn of the twentieth century, the process became controversial in the French wine industry with vignerons in the Languedoc protesting the production of "artificial wines" that flooded the French wine market and drove down prices. In June 1907, huge demonstrations broke out across the Languedoc region with over 900,000 protesters demanding that the government take action to protect their livelihood. Riots in the city of Narbonne prompted Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau to send the French army to the city. The ensuing clash resulted in the death of five protesters. The following day, Languedoc sympathizers burned the prefecture in Perpignan. In response to the protests, the French government increased the taxation on sugar and passed laws limiting the amount of sugar that could be added to wine.[6]

Process variations

[edit]

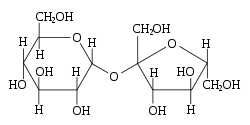

Different techniques are employed to adjust the level of sugar in the grape must. In the normal chaptalization process, cane sugar is the most common type of sugar added although some winemakers prefer beet sugar or corn syrup. In many wine regions, brown sugar is an illegal additive, and in regions that disallow chaptalization altogether, grape concentrate may be added.[3] After sugar is added to the must, naturally occurring enzymes break down the sucrose molecules in sugar into glucose and fructose, which are then fermented by the yeast and converted into alcohol and carbon dioxide.

In warmer regions, where overripening is a concern, the opposite process of rehydration (dilution with water) and acidification is used. This is used in jurisdictions such as areas of California, where if the must has excess sugar for normal fermentation, water may be added to lower the concentration. In acidification, tartaric acid is added to the must to compensate for the high levels[7] of sugar and low levels of acid naturally found in ripe grapes.[8]

In Champagne production, measured quantities of sugar, wine, and sometimes brandy are added after fermentation and prior to corking in a process known as dosage. Chaptalization, on the other hand, involves adding sugar prior to fermentation. Champagne producers sometimes employ chaptalization in their winemaking when the wine is still in the form of must.[3]

Some wine journalists contend that chaptalization allows wine makers to sacrifice quality in favor of quantity by letting vines overproduce high yields of grapes that have not fully ripened.[9] Also, winemakers have been using technological advances, such as reverse osmosis to remove water from the unfermented grape juice, thereby increasing its sugar concentration,[3] but decreasing the volume of wine produced.

Current legality

[edit]

Control of chaptalization is fairly strict in many countries, and generally only permitted in more northerly areas where grapes might not ripen enough. In the European Union, the amount of chaptalization allowed depends on the wine growing zone.

| Zone | Allowable increase[2] | Maximum ABV from chaptalization[2] |

|---|---|---|

| A | 3% ABV (24 g/L)[10] | 11.5% (white), 12% (red)[11] |

| B | 2% ABV (16 g/L) | 12% (white), 12.5% (red) |

| C | 1.5% ABV (12 g/L) Zero in Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Cyprus, and regions of southern France | 12.5%–13.5% depending on region |

Dispensation to add another 0.5% ABV may be given in years when climatic conditions have been exceptionally unfavorable.[12] National wine regulations may further restrict or ban chaptalization for certain classes of wine.

In some areas, such as Germany, wine regulations dictate that the wine makers must label whether or not the wines are "natural," i.e. without sugar. Other areas, such as France, do not have such label requirements.[5]

In the United States, federal law permits chaptalization when producing natural grape wine from juice with low sugar content.[13] This allows chaptalization in cooler states such as Oregon, or in states such as Florida where the native grape (Muscadine) is naturally low in sugar. However, individual states may still create their own regulations; California, for example, prohibits chaptalization,[14] although California winemakers may add grape concentrate.[15]

Countries and regions

[edit]| Countries and regions where chaptalization is permitted | Countries and regions where chaptalization is not permitted

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b MacNeil, K (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- ^ a b c "Council Regulation (EC) No 479/2008 on the common organisation of the market in wine" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union: 148/52–54 (Annex V). 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sogg, D (2002-03-31). "Inside Wine: Chaptalization". Wine Spectator. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

- ^ Phillips, R (2000). A Short History of Wine. Harper Collins. pp. 195–196. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ a b Johnson, H (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon and Schuster. p. 395. ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ Phillips, 291.

- ^ Daniel, Laurie (September–October 2006). "Hang Time". Oakland Magazine. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Robinson, J (2003). Jancis Robinson's Wine Course. Abbeville Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-7892-0883-0.

- ^ a b MacNeil, 278.

- ^ a b "Quality categories". German Wine Institute. 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-07-31. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ "Guide to EU Wine Regulations" (PDF). UK Food Standards Agency. October 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ "Europa.eu, Press releases rapid: Agriculture and Fisheries". European Parliament. 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ "United States Federal Regulations, Title 27, Section 24.177" (PDF). Department of the Treasury. 2004.

- ^ a b c Phillips, 198.

- ^ Herbst, Ron; Herbst, Sharon Tyler (1995). "Wine Dictionary - chaptalization". Barron's Educational Services, Inc.

- ^ Brazil Federal Law 7678/1988 (in Portuguese)

- ^ Brazil Federal Decree 99066/1990 (in Portuguese)

- ^ a b c Johnson, H; Robinson, J (2005). The World Atlas of Wine. Mitchell Beazley Publishing. p. 242. ISBN 1-84000-332-4.

- ^ Robinson, 270.

- ^ Johnson and Robinson, 326.

- ^ "What's Lurking in Your Wine? Fish Bladders, Egg Whites, and Mega Purple". 29 June 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Correção do grau alcoólico". 2 March 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "¿Qué es la chaptalización?". 5 July 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

External links

[edit]- Chorniak, Jeff (August–September 2002). "How Sweet It Is: Chaptalization". WineMaker Magazine. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2002-10-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Chaptalization Calculator

- Gabriel Yravedra. El fraude de la chaptalización en vinos de la Unión Europea. AMV Ediciones, Madrid, 2014.