Cottagecore

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Cottagecore[1] is an internet aesthetic and subculture concerned with an idealised rural lifestyle.[2][3] The aesthetic centres on traditional and vernacular architecture, clothing, interior design and crafts. Based primarily on the visual and material culture of rural Europe,[4] cottagecore was first named on Tumblr in 2018[5] and is related to similar internet aesthetics including goblincore and dark academia. A subculture of Millennials and Generation Z, cottagecore developed as a response to economic pressures faced by young people; the aesthetic emphasises sustainability, agrarianism and slow living.[6]

In British English, the term cottage typically denotes a small, cozy building. During English Feudalism, cottages housed cotters (peasant labourers), who served their manorial lord.[7] The term now describes many kinds of small house of rustic or traditional style. Cottages are often associated with cottage gardens, which prioritise informal design and a mixture of ornamental and edible plants. Notably, cottages are associated with non-urban landscapes. The aesthetics of cottages and cottage gardens may be evoked in rural houses or in more urban environments.

Aesthetic and lifestyle elements

[edit]

Cottagecore satisfies an "aspirational form of nostalgia" for its proponents, as well as an escape from many forms of stress and trauma.[8] The New York Times described it as a reaction to hustle culture and the advent of personal branding.[8] The Guardian called it a "visual and lifestyle movement designed to fetishise the wholesome purity of the outdoors."[9] Cottagecore emphasizes simplicity and a pastoral life as an escape from the dangers of the modern world.[10] It became highly popular on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.[11][9] By encouraging proponents to spend time in nature, cottagecore may facilitate physical and mental self-care.[12]

Fashion

[edit]Hipster fashion of the 2000s and 2010s prefigured many of the aesthetics of cottagecore. Continued interest in vintage clothing, facial hair, "authenticity", and co-opting aesthetics of past generations fueled a burgeoning cottagecore subculture after the hipster trend began to wane. Prairie clothing, pioneer clothing, homesteader clothing, Victorian silhouettes, wool, calico muslin, button downs, and worn leather are often incorporated into the cottagecore style.[13]

Analytics company EDITED identified that, besides floral prints and stripes, "Old-world, feminine shapes and details are integral to this aesthetic—milkmaid necklines, puff sleeves, ruffles and prairie-inspired midi dresses."[14] Marketing commentators noted that the trend fits with already available 1970s-inspired dresses, lace trim, and denim, and complemented the slow fashion trend.[14] Brands like Batsheva, Doen, and the Vampire's Wife became popular for their frilly, whimsical flowy dresses that fit the cottagecore aesthetic.[15]

Food and gardening

[edit]

The practices of homesteading reflect the philosophy of self-sufficiency of cottagecore. This could include growing one's own food in one's own garden, making meals from scratch, and baking one's own bread. Cottagecore gardening is intended to be environmentally friendly, often including permacultural farming practices.[16][17] For example, the cultivation of a variety of perennial and annual native plants (i.e. plants endemic to the areas near one's home) helps attract insects, including bees, and as such promotes biodiversity and increases pollination of food-producing crops.[17]

Crafts

[edit]Followers of cottagecore typically purchase secondhand, vintage, hand-built, or primitive furniture.[18][19] Popular hobbies are often related to self-sufficiency including quilting, knitting and crochet.[20]

Antecedents and cultural context

[edit]

While cottagecore arose as a named aesthetic in 2018, similar aesthetics and ideals existed prior to its inception. The pastoral genre developed by the Hellenistic Greeks characterised the rural Arcadia as an idyllic landscape in which shepherds and shepherdesses enjoy leisure.[21] The works of the Hellenistic poet Theocritus were primarily aimed at an educated urban class who sought an escape, physical or imaginative, from the filth and disease associated with city life. The Roman poet Virgil developed the genre by acknowledging contemporary issues through the pastoral device.[22] Pastoral escapism continued to be produced for the courtly audience of the Roman Empire in the format of novels such as Daphnis and Chloe from the second century AD.[22]

The fourteenth-century Italian Renaissance poet Petrarch was known for his hill-walking and gardening as well as his pastoral poetry.[22] English playwright William Shakespeare wrote two pastoral plays: As You Like It and A Winter’s Tale. Christopher Marlowe’s renowned poem The Passionate Shepherd to His Love inspired a poetic response written by Walter Raleigh, The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd, in which the speaker observes that Arcadian ideas were fallacies.[22]

In eighteenth-century Europe it was fashionable to build follies, ornamental structures often built in the style of classical architecture or to mimic rustic villages.[23] Marie Antoinette's Hameau de la Reine, a rustic model village, is a primary example of a folly in a pastoral style.

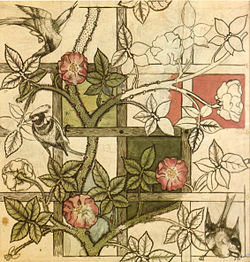

The Arts and Crafts movement of the nineteenth century was an approach to art, architecture, and design that embraced 'folk' styles and techniques as a critique of industrial production.[9] Several Victorian institutions including Morris & Co. and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood popularised a medievalist style, leading to a revived interest in rustic and vernacular architectural and furnishing styles.[24]

Thomas Kinkade sold millions of copies of his paintings of idyllic cottages.[25]

There have been similar aesthetics in specific countries, such as Japan's iki (detached elegance), Germany's fernweh (wanderlust), or Denmark's hygge (satisfying comfort).[26]

Contemporary popularity

[edit]The aesthetic gained traction in many online spheres and on social media in 2020 due to the mass quarantining in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[11][9][27] Networks such as the blogging site Tumblr had a 150% increase in cottagecore posts in the three months from March to May 2020.[14] It spread on Pinterest, a platform for sharing visual ideas.[28] It became popular on TikTok as well,[4][29] with numerous cottagecore enthusiasts sharing videos of themselves living in rural areas, bathing in the forest, or baking bread.[30]

On TikTok, the LGBTQIA+ community has been particularly fond of cottagecore, especially lesbians.[31] Many young women have found a sense of femininity through dressing in a cottagecore aesthetic while still feeling aligned with a modern, in-control woman archetype.[32] The New Yorker asserted that such videos had "evoked a mood of calm, enlightened, prettified productivity."[26] Vox characterized the trend as "the aesthetic where quarantine is romantic instead of terrifying."[5]

Living in the style of cottagecore or simply looking at others doing the same on the Internet was seen as something that could help people de-stress.[33] Speaking to CNN, psychologist Krystine Batcho noted that it should be no surprise nostalgia in general and cottagecore in particular was in vogue during such a stressful time. "Longing for simpler situations, simpler time periods or simpler ways of living is an effort to balance out and to counteract the effects of high intense stress," she said.[12] This was a period when many urban residents questioned whether it was worth living in the cities, and rural life stood up as an appealing alternative.[30]

A New York Times article compared cottagecore to the social simulation video game series Animal Crossing being acted out in real life, coinciding with the success of the then-newest entry in the franchise Animal Crossing: New Horizons.[8][9] In July 2021 The Sims 4 released an expansion pack called "Cottage Living", which focuses on floral prints, gardening and tending to animals like chickens and llamas.[34]

American musician Taylor Swift's 2020 album, Folklore, has been credited with increasing the aesthetic's popularity.[35][36][37] She continued the aesthetic with its follow-up record, Evermore (2020),[38][39] and applied it to her performance at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards.[40] The music videos for "Cardigan" and "Willow" both incorporate cottagecore imagery.[41] Other public figures who embraced this style include British actress Millie Bobby Brown,[42] American musician Hayley Kiyoko,[43] American model Hailey Bieber,[44] and English footballer David Beckham.[45]

In the United States, cottagecore became a decorating trend for the 2020 holiday season while the sales of needlework kits skyrocketed.[46] In 2021, the Royal Horticultural Society noted that cottage gardening was a key design style.[17]

China has its own version of cottagecore. Even though the country is rapidly urbanising as part of economic development, many young people have decided to leave the cities after their university studies for their hometowns in the countryside, where the quality of life has improved thanks to, among other things, the availability of fast Internet access, new roads, and high-speed railways.[47] Among the returning youths are cottagecore-minded architects.[48]

Critiques

[edit]According to critics, cottagecore offers an unrealistic, romanticised view of rural life.[8][18][19][49] Critics note the contrast between idyllic depictions of rural life constructed by the aesthetic and some of the realities of such spaces, such as the effects of rural poverty[12] or sanitation.[19] Lara Prendergast of The Spectator said "[p]rivileged humans have always hankered for the simple and rustic", and recalled historical criticisms levied against Marie Antoinette's mock-village, in which she would dress as a shepherdess while servants performed the manual labour necessary for its upkeep.[50]

Rebecca Jennings of Vox magazine described cottagecore and dark academia as "historical aesthetics that evoke conservative values and gender roles".[51] Jennings and others also noted themes of Eurocentrism and heteronormativity.[51][52]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "-core", Wikipedia, May 27, 2025, retrieved June 10, 2025

- ^ McGrath, Meadhbh (April 14, 2020). "Back to nature: Why cottagecore is the perfect escapism". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

... dubbed "cottagecore" (also "countrycore" and "farmcore"), it offers a romanticised vision of country life.

- ^ Edwards, Rachel (January 19, 2023). "How to achieve an authentic cottagecore aesthetic direct from the countryside". Country Living. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

Occasionally referred to as farmcore or countrycore, cottagecore romanticises the idea of living off the land ...

- ^ a b Tiffany, Kaitlyn (February 5, 2021). "Cottagecore Was Just the Beginning". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Jennings, Rebecca (August 3, 2020). "Cottagecore, Taylor Swift, and our endless desire to be soothed". Vox. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "'Cottagecore' and the rise of the modern rural fantasy". www.bbc.com. December 9, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2025.

- ^ Daniel D. McGarry, Medieval history and civilization (1976) p.242.

- ^ a b c d Slone, Isabel (March 10, 2020). "Escape Into Cottagecore, Calming Ethos for Our Febrile Moment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Hall, Amelia (April 15, 2020). "Why is 'cottagecore' booming? Because being outside is now the ultimate taboo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Bergado, Gabe (April 22, 2020). "Cottagecore Offers an Escape From Today's Stressful World". Teen Vogue. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Sunder, Kalpana (September 21, 2020). "Pie, flowers, pottery, knitting: why Taylor Swift loves cottagecore and how it's taking over social media during Covid-19". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Marples, Megan (February 7, 2021). "Cottagecore has us yearning for a bygone era that never was". CNN. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "How to Choose Cottagecore Outfits". Nvuvu. May 30, 2021. Archived from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Velasquez, Angela (June 10, 2020). "In Times of Crisis, Gen Z Embraces Escapist Fashion". Sourcing Journal. Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ Slone, Isabel (March 10, 2020). "Escape Into Cottagecore, Calming Ethos for Our Febrile Moment". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Crisfield, Max (April 17, 2021). "How to nail the cottagecore look in your garden in one day". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c "What's the buzz? Why the cottagecore garden trend is great for bees and biodiversity". The Guardian. April 5, 2021. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "What's it like to be 'cottagecore'?". BBC Bitesize. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Judkis, Maura (September 13, 2021). "Cottagecore, cluttercore, goblincore — deep down, it's about who we think we are". Style. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ Slone, Isabel (March 10, 2020). "Escape Into Cottagecore, Calming Ethos for Our Febrile Moment". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Introduction (p. 14) to Virgil: The Eclogues trans. Guy Lee (Penguin Classics)

- ^ a b c d Frey, Angelica (November 11, 2020). "Cottagecore debuted 2300 years ago". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Casid, Jill H. (Spring 1997). "Queer(y)ing Georgic: Utility, Pleasure, and Marie-Antoinette's Ornamented Farm". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 30 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 304–318. doi:10.1353/ecs.1997.0015. JSTOR 30054251. S2CID 162216322.

- ^ V. B. Canizaro, Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), p. 196.

- ^ Pickering, Corky (September 9, 2020). "The cottagecore dream during the pandemic". Red Bluff Daily News. MediaNews Group, Inc. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Chayka, Kyle (April 26, 2021). "TikTok and the Vibes Revival". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Bowman, Emma (August 9, 2020). "The Escapist Land Of 'Cottagecore,' from Marie Antoinette to Taylor Swift". NPR. Archived from the original on August 31, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Alterman, Liz (August 21, 2020). "What Is 'Cottagecore'? A Hot Decor Trend Thanks to COVID-19 and Taylor Swift". Real Estate. SF Gate. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Malbon, Abigail (July 24, 2020). "What is cottagecore? TikTok's latest aesthetic explained". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ a b AFP (August 3, 2020). "Cottagecore, the new lifestyle aesthetic that could dethrone hygge". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ White, Ro (September 30, 2020). "What Is Cottagecore and Why Do Young Queer People Love It?". Autostraddle. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Knowles, Samantha (September 9, 2020). "Cottagecore: a modern twist on a traditional feminine aesthetic". The Shorthorn. Archived from the original on October 27, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Schnalzer, Rachel (August 14, 2020). "Cottagecore is all over the internet. Here's where to experience it in California". Travel. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Carpenter, Nicole (July 8, 2021). "Cottage Living dragged my Sims outside to meet their neighbors". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 3, 2022. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Corr, Julieanne (January 17, 2021). "Taylor photo sparks Swift sales jump for Aran sweaters". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "A brief history of the cardigan, from Coco Chanel to Taylor Swift". RTÉ. July 27, 2020. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ Satran, Rory (January 9, 2021). "Taylor Swift's 'Evermore' Braid Is More Than Just a Braid". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Charlotte (December 16, 2020). "Cottagecore: The trend that defined Taylor Swift's new album". RTÉ. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Rao, Sonia (December 11, 2020). "How Taylor Swift and indie rock band the National became unlikely collaborators". Pop Culture. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Amatulli, Jenna (March 14, 2021). "Taylor Swift Serves Cottagecore Perfection With Medley During Grammys Performance". HuffPost. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Lefevre, Jules (December 11, 2020). "Taylor Swift's New Album Is Out And The First Video Is Cottagecore Heaven". Junkee. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Nesvig, Kara (May 18, 2020). "Millie Bobby Brown Jumped on the Cottagecore Bandwagon". Teen Vogue. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ "Hayley Kiyoko's New Video Is the Cottagecore Love Story of Our Dreams". Pride.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Dupes, Abby (July 26, 2022). "Hailey Bieber's Baby Blue Bikini and Tank Combo Is Peak Cottagecore — Shop the Look Here". Seventeen. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Elan, Priya (July 3, 2020). "David Beckham leads the way as men flock to 'cottagecore' look". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Cook, Kim (December 1, 2020). "Cottagecore holidays: Decorations with a homespun vibe". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "The gap between China's rural and urban youth is closing". The Economist. January 23, 2021. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Wainwright, Oliver (March 24, 2021). "China's rural revolution: the architects rescuing its villages from oblivion". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Klotz, Harper (March 22, 2021). "Cottagecore, a beautiful aesthetic with issues to address". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ Prendergast, Lara (April 29, 2021). "The curious rise of cottagecore". The Spectator. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Jennings, Rebecca (July 7, 2020). "This week in TikTok: Are you cottagecore or more "dark academia"?". Vox. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Martinez, Anna J. (September 20, 2021). "The Problems & Potential of Loving Cottagecore as a Woman of Color". Dismantle Magazine. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2023.