24 Hour Party People

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| 24 Hour Party People | |

|---|---|

UK theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Winterbottom |

| Written by | Frank Cottrell-Boyce |

| Produced by | Andrew Eaton |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Robby Müller |

| Edited by | Trevor Waite |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Pathé Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 minutes[2] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2.8 million[2] |

24 Hour Party People is a 2002 British biographical comedy drama film about Manchester's popular music community from 1976 to 1992, and specifically about Factory Records. It was written by Frank Cottrell Boyce and directed by Michael Winterbottom. The film was entered into the 2002 Cannes Film Festival[3] to positive reviews.

It begins with the punk rock era of the late 1970s and moves through the 1980s into the rave and DJ culture and the "Madchester" scene of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The main character is Tony Wilson (played by Steve Coogan), a news reporter for Granada Television and the head of Factory Records. The narrative largely follows his career, while also covering the careers of the major Factory artists, especially Joy Division and New Order, A Certain Ratio, The Durutti Column and Happy Mondays.[4]

The film is a dramatisation based on a combination of real events, rumours, urban legends and the imaginings of the scriptwriter, as the film makes clear.[4] In one scene, one-time Buzzcocks member Howard Devoto (played by Martin Hancock) is shown having sex with Wilson's first wife in the toilets of a club; the real Devoto, an extra in the scene, turns to the camera and says, "I definitely don't remember this happening". The fourth wall is frequently broken, with Wilson (who also acts as the narrator) frequently commenting on events directly to camera as they occur, at one point declaring that he is "being postmodern, before it's fashionable". The actors are often intercut with real contemporary concert footage, including the Sex Pistols gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall.

Plot

[edit]In 1976 television presenter Tony Wilson sees the Sex Pistols perform at the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall for the first time. Inspired, Wilson starts a weekly series of punk rock shows at a Manchester club, where the newly formed Joy Division perform, led by the erratic, brooding Ian Curtis.[3]

Wilson founds a record label, Factory Records,[3] and signs Joy Division as the first band; the contract is written in Wilson's blood and gives the Factory artists full control over their music. He hires irascible producer Martin Hannett to record Joy Division, and soon the band and label have a hit record. In 1980, just before Joy Division is to tour the United States, Curtis hangs himself. Joy Division rename themselves New Order and record a hit single, "Blue Monday".[3]

Wilson opens a nightclub, the Haçienda;[3] business is slow at first, but eventually the club is packed each night. Wilson signs another hit band, Happy Mondays, led by Shaun Ryder, and the ecstasy-fuelled rave culture is born.[5]

Despite the apparent success, Factory Records is losing money. Every copy of "Blue Monday" sold loses five pence, as the intricate packaging by Peter Saville costs more than the single's sale price. Wilson pays for New Order to record a new album in Ibiza, but after two years, they still have not delivered a record. He pays for the Happy Mondays to record their fourth studio album in Barbados, but Ryder spends all the money on drugs. When Wilson finally receives the album, he finds that Ryder has refused to record vocals, and all the tracks are instrumentals. At the Haçienda, ecstasy use is curbing alcohol sales and attracting gang violence.[5]

The Factory partners try to save the business by selling the label to London Records. However, Wilson reveals that the Factory does not hold contracts with any of its artists and, therefore, doesn't own a catalogue of recordings. This renders the company ultimately worthless and the deal falls through. While smoking marijuana on the roof of Haçienda after its closing night, Wilson has a vision of God, who assures Wilson he has earned a place in history.[4][5]

Cast

[edit]

|

Cameos

|

Production

[edit]Director Michael Winterbottom held talks with the BBC about financing the film, but the studio "weren’t convinced anyone was interested in Tony."[7] Once production got underway, Winterbottom emulated a documentary style of shooting and cinéma vérité, as cast members were encouraged to improvise and blocking was loose or non-existent. The character of Tony Wilson is an unreliable narrator who regularly breaks the fourth wall, referencing Wilson's job as a TV presenter.[7] Real documentary footage of the period was also spliced into the film.[8]

Steve Coogan and Wilson were acquainted before filming, having first met in 1975. When Coogan later worked on a Granada Television late night show, the two men occasionally socialized.[9] Winterbottom recalled that Wilson helped the production team make connections with "everyone involved in the scene."[7]

Production designer Mark Tildesley rebuilt the Haçienda nightclub interior to its exact proportions in a Manchester warehouse.[7][8] The original building had been demolished and replaced with luxury flats in 2002.[10] Coogan, who performed at the club in 1986, "got goosebumps when [he] walked into the re-created Haçienda." To achieve the needed atmosphere, the production ran it as a real nightclub for a couple of nights, and New Order worked the DJ booth.[7]

Reception and awards

[edit]The film holds a Metacritic score of 85/100.[11] Roger Ebert gave it four out of four.[12]

The film was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival, competing against other films the same year, including About Schmidt, and The Pianist.[13]

In 2019, The Guardian ranked the film 49th in its 100 best films of the 21st century list.[14]

Empire gave it four out of five, highlighting the film's director.[5]

As usual with anything related to Factory Records, the film received its own FAC catalogue number – posthumously, in a sense, as Factory had already been bankrupt for nearly a decade. 24 Hour Party People is known as FAC 401, being first on the hundred that features other video & multimedia releases.[15]

24 Hour Party People holds a rating of 87% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 99 reviews. The site's consensus states: "The colorful, chaotic 24 Hour Party People nimbly captures the spirit of the Manchester music scene."[6]

Soundtrack

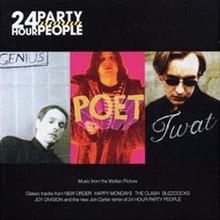

[edit]| 24 Hour Party People | |

|---|---|

| |

| Soundtrack album by various artists | |

| Released | 9 April 2002 |

| Recorded | 1976–2002 |

| Genre | Punk rock, post-punk, Madchester, electronica, house |

| Label | FFRR |

| Producer | Pete Tong |

| Alternative cover | |

US album cover | |

The soundtrack to 24 Hour Party People features songs by artists closely associated with Factory Records who were depicted in the film.[16] These include Happy Mondays, Joy Division (later to become New Order) and The Durutti Column. Manchester band the Buzzcocks are featured, as are The Clash. The album begins with "Anarchy in the U.K." by the Sex Pistols, the band credited in the film with inspiring Factory Records co-founder Tony Wilson to devote himself to promoting music.[16]

New tracks recorded for the album include Joy Division's "New Dawn Fades", from a concert performance by New Order with Moby and Billy Corgan.[16]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Allmusic | |

| Metacritic | (86/100)[18] |

| NME | (8/10)[19] |

| Pitchfork Media | (7/10)[20] |

| Rolling Stone | |

Track list

[edit]- "Anarchy in the U.K." (Sex Pistols) – 3:33 [16]

- "24 Hour Party People (Jon Carter Mix)" (Happy Mondays) – 4:30 [20]

- "Transmission" (Joy Division) – 3:36

- "Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn't've)" (Buzzcocks) – 2:42

- "Janie Jones" (The Clash) – 2:06

- "New Dawn Fades" (New Order featuring Moby) – 4:52

- "Atmosphere" (Joy Division) – 4:09

- "Otis" (The Durutti Column) – 4:16

- "Voodoo Ray" (A Guy Called Gerald) – 2:43

- "Temptation" (New Order) – 5:44

- "Loose Fit" (Happy Mondays) – 4:17

- "Pacific State" (808 State) – 3:53

- "Blue Monday" (New Order) – 7:30

- "Move Your Body" (Marshall Jefferson) – 5:15

- "She's Lost Control" (Joy Division) – 4:44

- "Hallelujah (Club Mix)" (Happy Mondays) – 5:40

- "Here To Stay" (New Order) – 4:58

- "Love Will Tear Us Apart" (Joy Division) – 3:24 [16]

Other songs in the film

[edit]Several songs appear in the film but are not on the soundtrack album, including:[20]

- "No Fun", performed by the Sex Pistols (archival video footage)

- "Money's Too Tight (to Mention)", performed by Simply Red (archival video footage)

- "Make Up to Break Up", performed by Siouxsie and the Banshees (archival video footage)

- "The Passenger", performed by Iggy Pop (archival video footage)

- "In The City", performed by The Jam (archival video footage)

- "No More Heroes", performed by The Stranglers (archival video footage)

- "Wimoweh", performed by Karl Denver (archival video footage)

- "Lazyitis", performed by Happy Mondays (archival video footage)

- "Old Lost John", performed by Sonny Terry (from the film Stroszek, during Ian Curtis suicide scene)

- "World in Motion", performed by New Order

- "Jacqueline", performed by The Durutti Column

- "Digital", performed by Joy Division

- "Flight", performed by A Certain Ratio

- "Skipscada", performed by A Certain Ratio

- "Tart Tart", performed by Happy Mondays

- "Freaky Dancin'", performed by Happy Mondays

- "Wrote for Luck", performed by Happy Mondays

- "Kinky Afro", performed by Happy Mondays

- "Sunshine and Love", performed by Happy Mondays

- "Satan", performed by Orbital

- "Go", performed by Moby

- "Louie Louie" (partial), performed by John The Postman

- "Louie Louie", performed by Factory All-Stars

- "King of the Beats", performed by Mantronix

- "Solid Air", performed by John Martyn

Chart positions

[edit]| Chart (2002) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[22] | 48 |

Networks

[edit]As of November 2023, the film was available for free on Roku, Pluto and Tubi streaming networks.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "24 Hour Party People (2002)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016.

- ^ a b "24 Hour Party People". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Festival de Cannes: 24 Hour Party People". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Smith, Evan (1 December 2013). "History and the Notion of Authenticity in Control and 24 Hour Party People". Contemporary British History. 27 (4): 466–489. doi:10.1080/13619462.2013.840537. ISSN 1361-9462. S2CID 159889143.

- ^ a b c d "24 Hour Party People". Empire. January 2000. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ a b "24 Hour Party People". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Phil Hoad (6 February 2023). "'I did my climactic speech – then took half an E': Steve Coogan on making 24 Hour Party People". theguardian.com. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Derek Elley (28 March 2002). "24 Hour Party People". variety.com. Variety Media. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Paul Morley (22 February 2001). "24 Hour Party People: shooting the past". theguardian.com. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ David Ward (29 August 2002). "Hacienda fans rave at plan for luxury flats". theguardian.com. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "24 Hour Party People". Metacritic. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "24 Hour Party People". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ "Official Selection 2002: All the Selection". festival-cannes.fr. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013.

- ^ "The 100 best films of the 21st century". The Guardian. 13 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "the factory records catalogue". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "24 Hour Party People". allmusic.com. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ 24 Hour Party People at AllMusic

- ^ "OST Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More at Metacritic". Metacritic. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Latest Reviews from NME.com – Music Videos, CDs, Gig Reviews & More". NME. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "Pitchfork: Album Reviews: Various Artists: 24 Hour Party People". Pitchforkmedia.com. 19 August 2002. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Various Artists: 24 Hour Party People". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Soundtrack – 24 Hour Party People". Hung Medien. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ "Where to Watch 24 Hour Party People". Roku. Retrieved 30 November 2023.