Donnell Óg O'Donnell

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

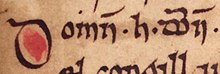

Donnell Óg O'Donnell (Irish: Domhnall Óg Ó Domhnaill; c. 1242-1281), was a medieval Irish king of Tyrconnell and member of the O'Donnell dynasty. He was a leading figure in the resistance to Anglo-Norman rule in the north west and closely related to many of the movement's most prominent figures, such as Hugh McFelim O'Connor, who is often credited as being the first to import Scottish gallowglass warriors. He should not be confused with a descendant of the same name who was a nephew of Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, and was the ultimate beneficiary-in-remainder to the Lordship of Tyrconnell.

Background and early career

[edit]Domhnall Óg was the posthumous[1] son of Domhnall Mór Ó Domhnaill, King of Tír Chonaill and his wife, Lasairfhíona, daughter of Cathal Crobhdhearg Ó Conchobhair, King of Connacht.[2] Lasairfhíona's aunt, Beanmhidhe, daughter of Toirdhealbhach Ó Conchobhair, was wife to the Scottish lord, Maol Mhuire an Sparáin, son of Suibhne mac Duinnshléibhe, whose kindred would become very important to Domhnall Óg's career.[3]

Tír Chonaill, centred on modern County Donegal, emerged from a confederation of tribes called the Cenél Conaill, claiming descent from the legendary figure Conall Gulban. Traditionally, leadership over Tír Chonaill alternated between rival branches of a sub-grouping known as the Cenél Aedha, which included the O'Muldory and O'Cannon families. Their seat of power was located in the barony of Tirhugh, in the south of modern County Donegal.

Éigneachán, father of Domhnall Mór, was the first of his lineage to assume rule of Tír Chonaill, in about 1200 C.E.[4] Previously, Éigneachán's family, the Cenél Luighdech, based around the site of the modern town of Ramelton, had been a tributary sept of Tír Chonaill.

Domhnall Mór succeeded his father in 1207 or 1208 and enjoyed a long and relatively peaceful reign until his death in 1241.[5]

However, the reigns of Domhnall Óg's older half-brothers, Maol Seachlainn and Gofraidh,[6] were troubled. Maol Seachlainn died at the Battle of Ballyshannon in 1247 fighting against Maurice FitzGerald, 2nd Lord of Offaly, after which Ruaidhrí Ó Canannáin was installed as ruler of Tír Chonaill. The lordship of Tír Chonaill changed hands twice before Gofraidh decisively recovered it in 1250.[7] Gofraidh himself died in 1258, perhaps as the result of wounds inflicted at the Battle of Creadran Cille in 1257, also fought against Maurice FitzGerald.[8]

In the wake of Gofraidh's death, there was a leadership crisis among the Cenél Conaill which their rivals, the Cenél nEógain, attempted to exploit by demanding tribute. It was at this point that an 18-year-old Domhnall Óg returned from fosterage among Clann Suibhne[9] in Scotland to succeed Gofraidh.[10][11]

Due to the influence of his upbringing, he was noted to speak in a strong Scottish dialect.[12]

King of Tír Chonaill

[edit]Domhnall Óg's reign saw not only a halt to the expansion of Anglo-Norman rule in the north west, but also the emergence of Tír Chonaill as a serious contender with the O'Neill dynasty for supremacy in Ulster, and an important player in politics across Ireland. He also claimed overlordship of northern Connacht. The Annals of the Four Masters record the following military exploits of Domhnall Óg as king of Tír Chonaill:

1259: A successful retaliatory raid on Tyrone and Oriel.[13]

1262: Wide reaching raids into Fermanagh, north Connacht and as far as County Longford.[14]

1263: Raids into Clanricarde in cooperation with Aodh na nGall Ó Conchobair (anglice "Hugh O'Conor") and on his own account into County Mayo.[15]

1272: A series of raids on the islands of Lough Erne.[16]

1273: A series of raids on the Cenél nEógain, apparently with several Connacht chieftains serving as tributaries.[17]

1275: He successfully defended Tír Chonaill against an incursion by Cenél nEógain, pursuing the attackers to their homes and taking great spoils.[18]

Domhnall Óg died in 1281 at the Battle of Disirt-dá-Chríoch (near modern Dungannon, Co. Tyrone) fighting against Aodh Buidhe O'Neill, founder of the Clanaboy branch of the O'Neill dynasty. He was succeeded as king of Tír Chonaill by his son, Aodh.[19]

Family and legacy

[edit]Domhnall Óg was married at least twice and had at least one son by each wife. His successor, Aodh, was the son of the daughter of Eoin Mac Suibhne, grandson of Maol Mhuire an Sparáin.[20][21] Domhnall Óg's son, Toirdhealbhach (also known as Turough), who later contested the kingship with Aodh and served as King of Tír Chonaill for several years, was the son of a daughter of Aonghus Mór, the founder of the Macdonald dynasty who were the Lords of the Isles.[22]

Domhnall Óg's reign was marked by a great consolidation of power within Tír Chonaill. He laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Mac Suibhne dynasty of gallowglass in Tír Chonaill when his father-in-law, Eoin Mac Suibhne, usurped the Ó Breisléins as lords of Fanad around 1263. The connection between Tír Chonaill and western Scotland pre-dated Domhnall Óg. For example, a member of the Mac Somhairle dynasty, possibly Ruaidhrí mac Raghnaill, died in the army of Domhnall Óg's elder half-brother Maol Seachlainn at the Battle of Ballyshannon. But after Domhnall Óg, the balance of power within Tír Chonaill would be determined less by relations among the traditional septs of Cenél Conaill than by feuding within the O'Donnell dynasty and their Mac Suibhne vassals, often with direct support from one Scottish magnate or another. No longer would its rule be in contention among the traditionally leading septs such as O'Muldory and O'Cannon. All subsequent rulers until the early modern period were direct descendants of Domhnall Óg.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) p. 111

- ^ Simms (2001) p. 14 tab. ii; McKenna (1946) p. 40.

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 86

- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) p. 103

- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) p. 104

- ^ Simms (2001) p. 14 tab. ii.

- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) p. 105

- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) pp. 110-111

- ^ Parkes (2006) p. 368 n. 19; Duffy (1993) pp. 127, 153; McKenna (1946) pp. 40, 42 § 22, 44 § 22.

- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) p. 110

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 74

- ^ Ó hUiginn (2016) p. 110

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 80

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 83

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 83

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 88

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 89

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 90

- ^ O'Clery (1845) p. 92

- ^ Parkes (2006) p. 368 n. 19.

- ^ Duffy (2002) p. 61; Duffy (1993) p. 153; Walsh (1938) p. 377.

- ^ Duffy (1993) p. 154.

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- McKenna, L (1946). "Some Irish Bardic Poems: LXXVII". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 35 (137): 40–44. ISSN 0039-3495. JSTOR 30099620.

- Walsh, P (1938). "O Donnell Genealogies". Analecta Hibernica (8): 373, 375–418. ISSN 0791-6167. JSTOR 30007662.

- O'Clery, Michael (1845). Connellan, Owen (ed.). The annals of Ireland, tr. from the orig. Irish of the Four masters by O. Connellan. Dublin: Oxford University. pp. 74, 80, 83, 86, 88, 89, 90, 92 – via Google Books.

- O’Donnell, Francis Martin (2018), The O'Donnells of Tyrconnell – A Hidden Legacy, Washington, D.C.: Academica Press LLC, ISBN 978-1-680534740 See pages 39 and 230.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Duffy, S (1993). Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318 (PhD thesis). Trinity College, Dublin – via Trinity's Access to Research Archive.

- Duffy, S (2002). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". In Duffy, S (ed.). Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 45–70. ISBN 0-7524-1974-9 – via Academia.edu.

- Parkes, P (2006). "Celtic Fosterage: Adoptive Kinship and Clientage in Northwest Europe" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 48 (2): 359–395. doi:10.1017/S0010417506000144. eISSN 0010-4175. ISSN 1475-2999. JSTOR 3879355.

- Simms, K (2001). "The Clan Murtagh O'Conors". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society. 53: 1–22. ISSN 0332-415X. JSTOR 25535718.

- Ó hUiginn, Ruairí (2016). "Annals, Histories, and Stories". In Boyd, Matthieu (ed.). Ollam: Studies in Gaelic and Related Traditions in Honor of Tomás Ó Cathasaigh. Stroud: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 101–114. ISBN 9781611478358.