Downtown Houston

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Downtown Houston | |

|---|---|

The Downtown skyline from the west. | |

Road map of Downtown Houston. | |

| Country | |

| State | Texas |

| County | Harris County |

| City | Houston |

| Settled | 1836 |

| Subdistricts | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.8 km2 (1.84 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 10,165 |

| • Density | 2,100/km2 (5,500/sq mi) |

| Greater Downtown (within 2 miles): 74,791 | |

| ZIP Code | 77002 |

| Area code(s) | 281, 346, 713, and 832 |

| Website | downtownhouston |

Downtown is the largest central business district in the city of Houston and the largest in the state of Texas, located near the geographic center of the metropolitan area at the confluence of Interstate 10, Interstate 45, and Interstate 69. The 1.84-square-mile (4.8 km2) district, enclosed by the aforementioned highways, contains the original townsite of Houston at the confluence of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou, a point known as Allen's Landing. Downtown has been the city's preeminent commercial district since its founding in 1836.

Today home to nine Fortune 500 corporations, Downtown contains 50 million square feet (4,600,000 m2) of office space and is the workplace of 150,000 employees.[1] Downtown is also a major destination for entertainment and recreation. Nine major performing arts organizations are located within the 13,000-seat Theater District at prominent venues including Alley Theatre, Hobby Center for the Performing Arts, Jones Hall, and the Wortham Theater Center. Two major professional sports venues, Minute Maid Park and the Toyota Center, are home to the Houston Astros and Houston Rockets, respectively. Discovery Green, an urban park located on the east side of the district adjacent to the George R. Brown Convention Center, anchors the city's convention district.

Downtown is Houston's civic center, containing Houston City Hall, the jails, criminal, and civil courthouses of Harris County, and a federal prison and courthouse. Downtown is also a major public transportation hub, lying at the center of the light rail system, park and ride system, and the metropolitan freeway network; the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO) is headquartered in the district. Over 100,000 people commute through Downtown daily.[1] An extensive network of pedestrian tunnels and skywalks connects a large number of buildings in the district; this system also serves as a subterranean mall.

Geographically, Downtown is bordered by East Downtown to the east, Third Ward to the south, Midtown to the southwest, Fourth Ward to the west, Sixth Ward to the northwest, and Near Northside to the north. The district's streets form a strict grid plan of approximately 400 square blocks,[2] oriented at a southwest to northeast angle. The northern end of the district is crossed by Buffalo Bayou, the banks of which function as a linear park with a grade-separated system of hike-and-bike trails.

Composition

[edit]Downtown Houston is a 1,178-acre (1.841 sq mi) area bounded by Interstate 45, Interstate 69/U.S. Highway 59, and Interstate 10/U.S. Highway 90.[3] Several sub-districts exist within Downtown, including:[4]

- Ballpark – Includes Minute Maid Park and surrounding restaurants, lofts, and office space.

- Convention – Includes the George R. Brown Convention Center, Discovery Green, the Toyota Center, and some of the largest hotels in the city.

- Civic Center – Contains the core of Houston's government, including City Hall – the Houston Public Library Central Library is also here,

- Harris County – The district includes the Harris County courts complex, and the University of Houston–Downtown is on the edge of the district.[5]

- Historic – This was the original town center of Houston and dates from the 19th century. The center of the historic district is the Market Square, where the original city hall building stood.

- Medical – located along Interstate 45 in the southern corner of the district; includes St. Joseph Medical Center, residential properties and the Sacred Heart Co-Cathedral campus.

- Shopping – Main Street Square has a pavilion and fountains built around the Main Street Square Station – GreenStreet and the Shops at Houston Center are in the area.

- Skyline – Includes many skyscrapers and forms the base of Downtown's employment. The buildings are connected by the extensive tunnel network.

- Theater – The 17 block area includes many performing arts venues, Bayou Place, and the Houston Aquarium.[5]

- Warehouse – Home to Houston's alternative art scene, unique dining options, live music, artists’ studios and downtown's first lofts.

History

[edit]

Downtown Houston encompasses the original townsite of Houston. After the Texas Revolution, two New York real estate investors, John Kirby Allen and Augustus Chapman Allen, purchased 6,642 acres (2,688 ha) of land from Thomas F.L. Parrot and his wife, Elizabeth (John Austin's widow), for US$9,428 (equivalent to $261,584 in 2023).[6] The Allen brothers settled at the confluence of White Oak and Buffalo bayous, a spot now known as Allen's Landing.

A team of three surveyors, including Gail Borden, Jr. (best known for inventing condensed milk) and Moses Lapham, platted a 62-square-block townsite in the fall of 1836, each block approximately 250 by 250 feet, or 62,500 square feet (5,810 m2) in size.[7] The grid plan was designed to conform to the winding route of Buffalo Bayou; east–west streets were aligned at an angle of north 55º west, while north–south streets were at an angle of south 35º west.[8] Each block was subdivided into 12 lots – five 50-by-100-foot lots on each side of the block, and two 50-by-125-foot lots between the rows of five.[8] The Allen brothers, motivated by their vision for urban civic life, specified wide streets to easily accommodate commercial traffic and reserved blocks for schools, churches, and civic institutions.[9] The townsite was then cleared and drained by a team of Mexican prisoners and black slaves.[9] By April 1837, Houston featured a dock, commercial district, the capitol building of the Republic of Texas, and an estimated population of 1,500.[9] The first city hall was sited at present-day Market Square Park in 1841; this block also served as the city's preeminent retail market.[10]

The relocation of the Texan republic's capital to Houston required a significant political campaign by the Allen brothers. The Allens gifted a number of city blocks to prominent Texas politicians and agreed to construct the new capitol building and a large hotel at no cost to the government.[8] The Allens also donated blocks to celebrities, relatives, prominent lawyers, and other influential people in order to attract additional investment and speculation to the town.[8] During the late 1830s and early 1840s, Houston was in the midst of a land boom, and lots were selling at "enormous prices," according to a visitor to the town in 1837.[8]

Despite the efforts of the Allen brothers and high economic interest in the town, first few years of Houston's existence were plagued by yellow fever epidemics, flooding, searing heat, inadequate infrastructure, and crime.[9] Houston suffered from woefully inadequate city services; the Allens failed to accommodate transit, water service, sewerage, road paving, trash service, or gas service in their plans.[8] As a result, in 1839 the Texas Capitol was moved to Austin.[9]

In 1840, Houston adopted a ward system of municipal governance, which, at the time, was considered more democratic than a strong-mayor system and had already been adopted by the United States' largest cities.[11] The boundaries of the original four wards of Houston radiated out from the intersection of Main and Congress streets; the First Ward was located to the northwest, Second to the northeast, Third to the southeast, and Fourth to the southwest.[11] Fifth Ward was created in 1866, encompassing the area north of Buffalo Bayou and east of White Oak Bayou; Sixth Ward, the final addition to the system, replaced the section of Fourth Ward north of Buffalo Bayou in 1877.[11] The ward system, which featured elected aldermen who served as representatives of each neighborhood, remained Houston's form of municipal government until 1905, when the city switched to a commission government and the wards, as political entities, were dissolved.[11]

Houston grew steadily throughout the late 19th century, and the neighborhoods within the boundaries of modern Downtown diversified. To the northeast, around present-day Minute Maid Park, Quality Hill emerged as an elite neighborhood, occupied by entrepreneurs like William Marsh Rice (namesake of Rice University), William J. Hutchins, and William L. Foley (namesake of Foley's department stores).[12] The neighborhood was well known for its opulent residential architecture, often in the Greek Revival style.[12] To the north, along a bend in Buffalo Bayou, the working-class neighborhood of Frost Town welcomed immigrants from Europe and Mexico during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[13]

Prior to the arrival of the first streetcars in Houston in the 1870s, most development in the city had been centered in and around the present-day Downtown area. One of the first systems, the Houston City Street Railway, opened in 1874 with four lines along the principal commercial thoroughfares in the heart of the business district.[14] While generally focused on the most prosperous areas of town, the Houston City Street Railway extended one line a full mile south of the center of the city, making it the first streetcar network designed to spur residential development.[14] By the 1890s, new, larger local streetcar companies finally accumulated the capital necessary to begin constructing streetcar suburbs beyond the conventional boundaries of the city.[14] This led to the development and rapid growth of areas like the Houston Heights and Montrose.[14] Residential development subsequently moved out of the central business district; Quality Hill was virtually abandoned by the turn of the 20th century.[12]

Downtown's growth can be attributed to two major factors: The first arose after the Galveston Hurricane of 1900, when investors began seeking a location close to the ports of Southwest Texas, but apparently free of the dangerous hurricanes that frequently struck Galveston and other port cities. Houston became a wise choice, as only the most powerful storms were able to reach the city. The second came a year later with the 1901 discovery of oil at Spindletop, just south of Beaumont, Texas. Shipping and oil industries began flocking to east Texas, many settling in Houston. From that point forward the area grew substantially, as many skyscrapers were constructed, including the city's tallest buildings. In the 1980s, however, economic recession canceled some projects and caused others to be scaled back, such as the Bank of the Southwest Tower.[15]

- Bird's-eye view looking up Main Street, Houston, Texas (postcard, circa 1912–1924)

- Bird's-eye view, Houston, Texas (circa 1907)

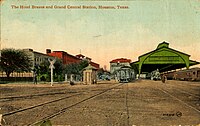

- Hotel Brazos and Grand Central Station, Houston, Texas (postcard, circa 1911)

- Downtown Houston in 1927

- View from the Scanlan Building, Houston, Texas (postcard, circa 1910)

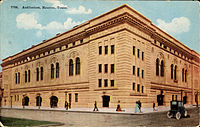

- City Auditorium, Houston, Texas (postcard, circa 1910)

- Opera House, Houston, Texas (postcard, circa 1958)

In the 19th century much of what was the Third Ward, the present day east side of Downtown Houston, was what Stephen Fox, an architectural historian who lectured at Rice University, referred to as "the elite neighborhood of late 19th-century Houston." Ralph Bivins of the Houston Chronicle wrote that Fox said that area was "a silk-stocking neighborhood of Victorian-era homes." Bivins said that the construction of Union Station, which occurred around 1910, caused the "residential character" of the area to "deteriorate." Hotels opened in the area to service travelers. Afterwards, according to Bivins, the area "began a long downward slide toward the skid row of the 1990s" and the hotels devolved into flophouses. Passenger trains stopped going to Union Station in 1974.[16] The construction of Interstate 45 in the 1950s separated portions of the historic Third Ward from the rest of the Third Ward and brought those portions into Downtown.[17]

Beginning in the 1960s the development of the 610 Loop caused the focus of the Houston area to move away from Downtown Houston. Joel Barna of Cite 42 said that this caused Greater Houston to shift from "a fragmenting but still centrally focused spatial entity into something more like a doughnut," and that Downtown Houston began to become a "hole" in the "doughnut." As interchange connections with the 610 Loop opened, according to Barna Downtown "became just another node in a multi-node grid" and, as of 1998, "has been that, with already established high densities and land prices." In the mid-1980s, the bank savings and loan crisis forced many tenants in Downtown Houston buildings to retrench, and some tenants went out of business. Barna said that this development further caused Downtown Houston to decline.[18]

The Gulf Hotel fire occurred in 1943.

Areas which are now considered part of Downtown were once within Third and the Fourth wards; the construction of Interstate 45 in the 1950s separated the areas from their former communities and placed them in Downtown. Additional freeway construction in the 1960s and 1970s solidified the current boundaries of Downtown. Originally, Downtown was the most important retail area of Houston. Suburban retail construction in the 1970s and 1980s reduced Downtown's importance in terms of retail activity.[17]

From 1971 to 2018, about 40 downtown buildings and other properties have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The onset of the 1980s oil glut had devastating economic consequences for Downtown. In the mid-1980s, a bank savings and loan crisis forced many tenants in Downtown Houston buildings to retrench, and some went out of business. This development further caused Downtown Houston to decline.[18] In 1986, Downtown's Class A office occupancy rate was 81.4%.[19] The Downtown Houston business occupancy rate of all office space increased from 75.8% at the end of 1987 to 77.2% at the end of 1988.[20] By the late 1980s, 35% of Downtown Houston's land area consisted of surface parking.[18] In the early 1990s Downtown Houston still had more than 20% vacant office space.[21] By 1987 many of the office buildings in Downtown Houston were owned by non-U.S. real estate figures.[22]

Downtown began to rebound from the oil crisis by the mid-1990s. A dozen companies relocated to Downtown in 1996 alone, bringing 2,800 jobs and filling 670,000 square feet (62,000 m2) of space.[23] In 1997 Tim Reylea, the vice president of Cushman Realty, said that "None of the major central business districts across the country has seen the suburban-to-downtown shift that Houston has."[24] Circa 2000 the Ballpark at Union Station/Enron Field, now Minute Maid Park, opened, Houston Downtown Management District president Bob Eury stated that this promoted subsequent development in Downtown.[25]

By 2000, demand for Downtown office space increased, and construction of office buildings resumed.[21] The cutbacks by firms such as Dynegy, in addition to the fall of Enron, caused the occupancy rate of Downtown Houston buildings to decrease to 84.1% in 2003 from 97.3% less than two years previously. In 2003, the types of firms with operations in Downtown Houston typically were accounting firms, energy firms, and law firms. Typically newer buildings had higher occupancy rates than older buildings.[19] In 2004, the real estate firm Cresa Partners stated that the vacancy rate in Downtown Houston's Class A office space was almost 20%.[26] The Texas Legislature established the Downtown Houston Management District in 1995.[3]

Circa/after the 1990s, Downtown has experienced a boom in high-rise residential construction, spurred in large part by the Downtown Living Initiative (DLI), a tax incentive program created by the city. Between 2013 and 2015, the DLI subsidized 5,000 proposed residential units. As a result, Downtown's residential population has increased to 10,165 people in 4,777 units, up from 900 units in the 1995.[1][27] Many of Downtown's older residential units are located in lofts and converted commercial space, many of which are located around the performance halls of the Houston Theater District and near Main Street in the Historic District.[citation needed] In spring 2009, luxury high-rise One Park Place opened-up with 346 units.[28] In early 2017 Downtown's largest residential building opened when Market Square Tower's 463 units were completed.

Developers have invested more than US$4 billion in the first decade of the 21st century to transform Downtown into an active city center with residential housing, a nightlife scene and new transportation.[29] The Cotswold Project, a $62 million project started in 1998, has helped to rebuild the streets and transform 90 downtown blocks into a pedestrian-friendly environment by adding greenery, trees and public art.[30] January 1, 2004, marked the opening of the "new" Main Street, a plaza with many eateries, bars and nightclubs, which brings many visitors to a newly renovated locale.[31]

Phoenicia Specialty Foods opened a downtown grocery store in 2011, located in One Park Place.[32][33]

In June 2019 Dianna Wray of Houstonia wrote that Downtown Houston had an increased amount of pedestrian traffic and residents compared to the post-oil bust 1980s.[25]

Office traffic declined during the COVID-19 pandemic in Texas. By 2022 many offices had split shifts to where workers only went to offices for some days of the week.[34] By 2022 activity at hotel and entertainment establishments recovered.[35]

In May 2024, a derecho struck the downtown Houston causing damage.[36]

Architecture

[edit]

In the 1960s, downtown comprised a modest collection of mid-rise office structures, but has since grown into one of the largest skylines in the United States. In 1960, the central business district had 10 million square feet (930,000 m2) of office space, increasing to about 16 million square feet (1,500,000 m2) in 1970. Downtown Houston was on the threshold of a boom in 1970 with 8.7 million square feet (800,000 m2) of office space planned or under construction and huge projects being launched by real estate developers. The largest proposed development was the 32-block Houston Center. Only a small part of the original proposal was ultimately constructed, however. Other large projects included the Cullen Center, Allen Center, and towers for Shell Oil Company. The surge of skyscrapers mirrored the skyscraper booms in other cities, such as Los Angeles and Dallas. Houston experienced another downtown construction spurt in the 1970s with the energy industry boom.[37]

The first major skyscraper to be constructed in Houston was the 50-floor, 218 m (715 ft) One Shell Plaza in 1971. A succession of skyscrapers were built throughout the 1970s, culminating with Houston's tallest skyscraper, the 75-floor, 305 m (1,001 ft) JPMorgan Chase Tower (formerly the Texas Commerce Tower), which was completed in 1982. In 2002, it was the tallest structure in Texas, ninth-tallest building in the United States, and the 23rd tallest skyscraper in the world. In 1983, the 71-floor, 296 m (971 ft) Wells Fargo Plaza was completed, which became the second-tallest building in Houston and Texas, and 11th-tallest in the country. Skyscraper construction in downtown Houston came to an end in the mid-1980s with the collapse of Houston's energy industry and the resulting economic recession.[38]

Twelve years later, the Houston-based Enron Corporation began constructing a 40-floor, 1,284,013sq.ft[39] skyscraper in 1999 (which was completed in 2002)[40] with the company collapsing in one of the most dramatic corporate failures in the history of the United States only two years later. Chevron bought this building to set up a regional upstream energy headquarters, and in late 2006 announced further consolidation of employees downtown from satellite suburban buildings, and even California and Louisiana offices by leasing the original Enron building across the street. Both buildings are connected by a second-floor unique walk-across, air-conditioned circular skybridge with three points of connection to both office buildings and a large parking deck. Other smaller office structures were built in the 2000–2003 period. As of January 2015, downtown Houston had more than 44 million square feet (4,087,733 m2) of office space, including more than 29 million square feet (1,861,704 m2) of class A office space.[41][42]

Notable buildings

[edit]

Notable buildings that form Houston's downtown skyline:

- The Sweeney, Coombs, and Fredericks Building is a late Victorian commercial building with a 3-story corner turret and Eastlake decorative elements that was designed by George E. Dickey in 1889. Evidence indicates that the 1889 construction may have been a renovation of an 1861 structure built by William A. Van Alstyne and purchased in 1882 by John Jasper Sweeney and Edward L. Coombs. Gus Fredericks joined the Sweeney and Coombs Jewelry firm before 1889. The building is on the corner of Main Street and Congress Street at 301 Main Street. The jewelry firm is still in business. It is one of the very few Victorian structures in the Bayou City.

- The Gulf Building, now called the JPMorgan Chase building, is one of the preeminent Art Deco skyscrapers in the southern United States. Completed in 1929, it remained the tallest building in Houston until 1963, when the Exxon Building surpassed it in height.

- The Esperson Buildings, 'Neils' built in 1927 and 'Mellie' in 1942, were modeled with Italian architecture.

- The Houston City Hall was started in 1938 and completed in 1939. The original building is an excellent example of the Art Deco Era. In front of City Hall is the George Hermann Square.

- The Alley Theatre was completed in 1968. It is home to the Tony Award winning theatre company by the same name, the oldest professional theatre company in Texas. Its nine towers and brutality style give it a castle appearance.

- One Shell Plaza was, at its completion in 1971, the tallest building in Houston. It stands 715 feet (218 m) tall, and when the antenna tower on its top is included, the height of One Shell Plaza is 1,000 feet (300 m).

- Houston Public Library's Central Library, consists of two separate buildings: the Julia Ideson Building (1926) and the Jesse H. Jones Building (1976).

- The Houston Industries Building, formerly known as the 1100 Milam Building, was built in 1973. It went through major renovations in 1996.

- Pennzoil Place, designed by Philip Johnson, built in 1976, is Houston's most award-winning skyscraper, known for its innovative design. Johnson's forward thinking brought about a new era in skyscraper design.

- The First City Tower was built in 1981.

- The JPMorgan Chase Tower, designed by I.M. Pei, was built in 1981. Formerly the Texas Commerce Tower, it is the tallest in Houston and the second tallest in the United States west of the Mississippi River.

Scanlan Building, Houston, Texas (postcard, circa 1912–1924) - The Chevron Tower, formerly the Gulf Tower, was built in 1982.

- The Bank of America Center, formerly the RepublicBank Center and the NationsBank center, designed by Philip Johnson, was built in 1983.

- The Wells Fargo Bank Plaza, formerly the Allied Bank Plaza and First Interstate Center, also built in 1983, is the second tallest building in the Houston Area.

- The Heritage Plaza was completed in 1987.

- The Enron Center North, also known as the Four Allen Center, was also built in 1983.

- The Enron Center South, also the Enron II, designed by Cesar Pelli was completed in 2002. (Note: Enron went bankrupt before the building's completion and was sold soon after it was completed for about half of its $200 million construction cost).

- The Hobby Center for the Performing Arts was started in 2000 and completed in 2002.

- The Lyric Centre, named for its adjacency to the Theater District.

- The Carter Building, once the tallest building in Texas, more recently re-purposed as a hotel.

- The Scanlan Building, at Main and Preston, was built on the site of the first official "White House" of the Republic of Texas. Constructed in 1909 by the daughters of Thomas Howe Scanlan to honor their father, former mayor of Houston (1870–1873). The Scanlan Building is listed in the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and was the largest building in the city at the time of its construction.

Demographics

[edit]In 2017 the Downtown Super Neighborhood #61, which includes Downtown and East Downtown, had 12,879 people. 34% were non-Hispanic White, 28% were Hispanic, 32% were non-Hispanic Black, 4% were non-Hispanic Asians, and 2% were non-Hispanic people of other racial identities.[43]

In 2015 there were 12,407 residents. 33% were non-Hispanic White, 32% were non-Hispanic Black, 29% were Hispanic, 5% were non-Hispanic Asian, and 1% were non-Hispanics of other racial identities.[44]

In 2000 there were 12,407 residents. 5,083 (41%) were non-Hispanic Black, 4,225 (34%) were non-Hispanic White, 2,872 (23%) were Hispanic, 156 (1%) were non-Hispanic Asians, 56 were of two or more races, 11 were non-Hispanic American Indian, and two each were non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian and non-Hispanic people of other racial identities.[45]

Economy

[edit]Downtown is Houston's single largest office market, containing 50 million square feet (4,600,000 m2) of space.[1] A premium submarket, Downtown commands the highest office rental rates in the city[46] and was one of the ten most expensive office markets in the United States in 2016.[47] Louisiana Street, which runs through the heart of the district, is one of the fifteen most expensive streets in the United States.[48]

3,500 businesses in the district employ approximately 150,000 workers. Major employers include Chevron, JPMorgan Chase, and United Airlines.[3] Downtown Houston has between 35% and 40% of the Class A office locations of the business districts in Houston.[49]

Companies based in Downtown

[edit]

Firms which are headquartered in Downtown include:

- Calpine

- Dynegy in Wells Fargo Plaza[50]

- KBR[51][52]

- Baker Botts in One Shell Plaza[53][54]

- Bracewell LLP in Pennzoil Place[55]

- Total Petrochemicals USA in Total Plaza[56][57]

- CenterPoint Energy in CenterPoint Energy Plaza[58][59]

- Vinson & Elkins in Texas Tower [60][61]

- Waste Management in First City Tower[62]

- El Paso Corp.[63]

- Plains All American Pipeline in Allen Center[64]

- Enterprise GP Holdings in Enterprise Plaza[65]

- EOG Resources in Heritage Plaza[66]

Companies with operations in Downtown

[edit]Continental Airlines (now known as United Airlines) formerly had its headquarters in Continental Center I.[67] At one point, ExpressJet Airlines had its headquarters in Continental's complex.[68][69] In September 1997 Continental Airlines announced it would consolidate its Houston headquarters in the Continental Center complex;[70] the airline scheduled to move its employees in stages beginning in July 1998 and ending in January 1999. Bob Lanier, Mayor of Houston, said that he was "tickled to death" by the airline's move to relocate to Downtown Houston.[71] Tim Reylea, the vice president of Cushman Realty, said that the Continental move "is probably the largest corporate relocation in the central business district of Houston ever."[24]

Hotel operators in Downtown reacted favorably, predicting that the move would cause an increase in occupancy rates in their hotels.[72] In 2008 Continental renewed its lease in the building. Before the lease renewal, rumors spread stating that the airline would relocate its headquarters to office space outside of Downtown. Steven Biegel, the senior vice president of Studley Inc. and a representative of office building tenants, said that if Continental's space went vacant, the vacancy would not have had a significant impact in the Downtown Houston submarket as there is not an abundance of available space, and the empty property would be likely that another potential tenant would occupy it. Jennifer Dawson of the Houston Business Journal said that if Continental Airlines left Continental Center I, the development of Brookfield Properties's new office tower would have been delayed.[73] As of September 2011 the headquarters moved out, but Continental will continue to house employees in the building. It will have about half of the employees that it once had.[74]

JPMorgan Chase Bank has its Houston operations headquartered in the JPMorgan Chase Building (Gulf Building).[75] LyondellBasell has offices in the LyondellBasell Towers formerly known as 1 Houston Center.[76] Hess Corporation has exploration and production operations in One Allen Center.,[77] but will move its offices to the under construction Hess Tower (Named after the company) upon its completion.[78]

ExxonMobil has Exploration and Producing Operations business headquarters at the ExxonMobil Building.[79] Qatar Airways operates an office within Two Allen Center;[80] it also has a storefront in the Houston Pavilions.[81][82] Enbridge has its Houston office in the Enterprise Plaza.[83] KPMG has their Houston offices in the new BG place at 811 Main St. Mayer Brown has his Houston office in the Bank of America Center.[84][85]

Former economic operations

[edit]When Texas Commerce Bank existed, its headquarters were in what is now the JPMorgan Chase Building (Gulf Building).[75] Prior to its collapse in 2001, Enron was headquartered in Downtown.[86] In 2005 Federated Department Stores announced that it will close Foley's 1,200 employee headquarters in Downtown Houston.[87]

Houston Industries (HI, later Reliant Energy) and subsidiary Houston Power & Lighting (HL&P) historically had their headquarters in Downtown.[88]

Halliburton's corporate headquarters office was in 5 Houston Center.[89] In 2001, Halliburton canceled a move to redevelop land in Westchase to house employees; real estate figures associated with Downtown Houston approved of the news. Nancy Sarnoff of the Houston Business Journal said it made more sense for the company to lease existing space instead of constructing new office space in times of economic downturns.[90] By 2009 Halliburton closed its Downtown Office, moved its headquarters to northern Houston, and consolidated operations at its northern Houston and Westchase facilities.[91]

Government

[edit]Local government

[edit]

Two city council districts, District H and District I, cover portions of Downtown.[92][93] As of 2015 Mayor Pro-Tem Ed Gonzalez and Robert Gallegos, respectively, represent the two districts.[94]

Houston City Hall, the Margaret Helfrich Westerman Houston City Hall Annex, and the Bob Lanier Public Works Building are all located in Downtown Houston.

The community is within the Houston Police Department's Downtown Division.[95] The Edward A. Thomas Building, headquarters of HPD, is located in 1200 Travis Downtown.[96]

Houston Fire Department Station 8 Downtown at 1919 Louisiana Street serves the central business district. Station 8 is in Fire District 8.[97] The fire station "Washington #8" first opened in 1895 at Polk at Crawford. The station was closed in 2001 after a sports arena was built on the site.[98] Fire Station 1, which was located at 410 Bagby Street, closed in 2001,[97] as it was merged with Station 8. Station 8, relocated to a temporary building at the corner of Milam and St. Joseph, reopened in June 2001. The current "Super Station" at 1919 Louisiana opened on April 21, 2008.[98] "Stonewall #3," organized in 1867, was located in the current location of the Post Rice Lofts. It 1895 it moved to a location along Preston Street, between Smith and Louisiana, in what is now Downtown. The station, currently Station #3, moved outside of the current day Downtown in 1903.[99] Fire Station 5, originally in what was then the Fifth Ward, moved to Hardy and Nance in what is now Downtown in 1895. The station was rebuilt at that site in 1932, and in 1977 the station moved to Spring Branch.[100] Station 2 moved from what is now the East End to what is now Downtown in 1926. The station moved to the Fourth Ward in 1965.[101]

The Houston Downtown Management District and Central Houston, Inc. is headquartered in Suite 1650 at 2 Houston Center, a part of the Houston Center complex.[102]

County representation

[edit]

Downtown is divided between Harris County Precinct 1 and Harris County Precinct 2.[103] As of 2016, Gene L. Locke heads Precinct 1.[104] As of 2016, Jack Morman heads Precinct 2.[105] Harris County Precinct Two operates the Raul C. Downtown Courthouse annex in Downtown.[106]

The Harris County court system is located within a five block area bounded by Franklin, San Jacinto, Caroline, and Congress Streets. This complex includes the following:[107][108]

- Harris County Civil Court

- Harris County Family Court

- Harris County Juvenile Court

- Harris County Criminal Court

- Harris County Justice of the Peace, Precinct 1, Place 2

All are located around a central plaza, nicknamed "Justice Square", located above the underground Harris County Jury Plaza.[109] Along with Harris County's facilities, there are several constable courts and support facilities nearby.

The Harris County jail facilities are in northern Downtown on the north side of the Buffalo Bayou. The 1200 Jail,[110] the 1307 Jail, (originally a Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) facility, leased by the county),[111] and the 701 Jail (formed from existing warehouse storage space) are on the same site.[112]

The nearest public health clinics of Harris Health System (formerly Harris County Hospital District) were as of 2000 Ripley Health Center (for ZIP codes 77002, 77003, and 77010) in the East End and Casa de Amigos Health Center (for ZIP code 77007).[113] In 2000 Ripley was replaced by the Gulfgate Health Center.[114] The nearest public hospital is Ben Taub General Hospital in the Texas Medical Center.[113]

State representation

[edit]Much of Downtown is located in District 147 of the Texas House of Representatives. As of 2016, Garnet F. Coleman represents the district.[115] Some of Downtown is located in District 148 of the Texas House of Representatives. As of 2016, Jessica Farrar represents the district.[116] Downtown is within District 13 of the Texas Senate; as of 2016 Rodney Ellis represents that district.[117]

Joe Kegans Unit, located in Downtown, is a Texas Department of Criminal Justice state jail for men. It is adjacent to the county facilities on the north side of the Buffalo Bayou.[118] Kegans opened in 1997.[119] The South Texas Intermediate Sanction Facility Unit, a parole confinement facility for males operated by Global Expertise in Outsourcing, is in Downtown Houston, west of Minute Maid Park.[120]

As of 2011, the Texas First Court of Appeals and the Texas Fourteenth Court of Appeals are located in the renovated 1910 Courthouse.[121][122]

Federal representation

[edit]

Downtown Houston is in Texas's 18th congressional district.[123] Its representative was Sheila Jackson Lee[124] who died on July 19th, 2024, from cancer at the age of 74. The seat is now vacant.[125][126]

The United States Postal Service previously operated a 16-acre (65,000 m2) Houston Post Office at 401 Franklin Street.[127] The building, named after Barbara Jordan, was designed by the architects who designed the Houston Astrodome, opened in 1962 and received its current name in 1984.[128] When it was a post office it had mail sorting machines. It has 555,000 square feet (51,600 m2) of space.[129] However, following the sale of the property, the U.S. Postal Service ceased operations at the facility on May 15, 2015, and consolidated its sorting operations.[130][131] The Sam Houston Station,[132] the new Houston Post Office on Hadley Street in Midtown Houston assumed the role held by the previous one.[133] In 2010 the Houston Press ranked the former Downtown post office as the best post office in Houston.[134] It became an event venue called Post HTX after the company Lovett Commercial took control of it in 2015.[135] By 2021 it was being redeveloped as a shopping center.[129]

In addition the USPS operates the 2 Houston Center and Civic Center postal units. In July 2011 the USPS announced that the two postal units may close.[136]

Regional offices of U.S. government agencies are located at the Mickey Leland Federal Building at 1919 Smith Street. The 22 story building, with a 6-story parking garage, was designated an Energy Star efficient building in 2000.[137]

The United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas has its offices in 515 Rusk in Downtown Houston.[138]

The Federal Bureau of Prisons operates the Federal Detention Center, Houston in Downtown.[139]

Diplomatic missions

[edit]The Consulate-General of the United Kingdom is located in Wells Fargo Plaza,[140] while the Consulate-General of Japan is located in Two Houston Center.[141] The Consulate-General of Switzerland, which resided in Downtown Houston, closed in 2006.[142][143][144][145]

Parks, recreation, and culture

[edit]Downtown contains fifteen public parks, varying from linear parks along Buffalo Bayou to block parks and plazas.

On the west side of Downtown along Bagby Street, Sam Houston Park is home to the Houston Heritage Society, which maintains a collection of historic houses from throughout the city's history. Nearby, Tranquility Park uses open green spaces and a series of interconnected fountains to commemorate NASA's landing on the moon's Sea of Tranquility. These parks tie into the larger civic complex anchored by City Hall and the main branch of Houston Public Library.

In the Historic District to the north, Market Square Park occupies a block formerly covered by Houston's open air market which fronted the old City Hall. Renovations completed in 2010 added two dog runs, a Greek restaurant, and Houston's only memorial to the September 11 attacks.[146][147]

Buffalo Bayou's route through Downtown contains multiple parks which segue together to form a continuous greenway. Allen's Landing, near the intersection of Smith and Preston, commemorates the landing site of the Allen brothers, the New York entrepreneurs who founded the city. Sesquicentennial Park, across Buffalo Bayou from Allen's Landing, commemorates the 150-year anniversary of the city's founding. The park contains a statue of former President George H. W. Bush, who represented a portion of west Houston during his time in the United States House of Representatives.

In the Convention District, Discovery Green, immediately west of the George R. Brown Convention Center, contains an amphitheater, two restaurants, a dog run, a jogging trail, multiple lawns, and an artificial lake on nearly 12 acres (49,000 m2) of land.[148] Since its opening in 2008, Discovery Green has become one of Downtown's main attractions, hosting approximately 1.2 million visitors a year and serving as one of the city's premier public spaces.[149] Discovery Green's environs, formerly covered by surface parking lots, have seen over US$600 million in new development since the park's opening.[150]

A number of other smaller parks and plazas are spread throughout Downtown. Main Street Square is a pedestrian-only promenade with a reflection pool and fountains on the METRORail line between Lamar and Dallas streets.[151] Near the Toyota Center, Root Square occupies a single block and features a public basketball court.[152] Harris County Precinct One operates the 2-acre (8,100 m2) Quebedeaux Park near the county court complex.[153] The park includes a stage area, picnic tables, and benches. The park surrounds the Harris County Family Law Center.[154]

A park in the southern part of Downtown, Trebly Park, began construction in March 2021 on the site of a former automobile repair center. The park had the provisional name Southern Downtown Park; its chosen name refers to how there are three street corners adjacent to the park.[155] The area is in the shape of an "L".[156]

Entertainment venues

[edit]

Downtown Houston has two major league sports venues. Minute Maid Park, opened in 2000, is home to MLB Houston Astros, and the Toyota Center, opened in 2003, is home to the NBA Houston Rockets. From 2004 to 2007, Toyota Center was also home to the now defunct WNBA Houston Comets.

The Theater District is one of the largest in the country as measured by the number of theater seats.[citation needed] Houston is one of only five cities in the United States with permanent professional resident companies in all of the major performing art disciplines of opera, ballet, music, and theater.[citation needed] Venues in the theater district include the Wortham Center (opera and ballet), the Alley Theatre (theater), the Hobby Center (resident and traveling musical theater, concerts, events), the Bayou Music Center (concerts and events) and Jones Hall (symphony).

The George R. Brown Convention Center is located on the east side of Downtown, between Discovery Green and Interstate 69, and contains 1,800,000 square feet (170,000 m2) of convention space and two adjoining hotels. In the mid-2010s, the promenade between the Center and Discovery Green was transformed into Avenida Houston, a mixed-use corridor featuring restaurants and retail spaces.[157]

Hotels and accommodations

[edit]Major hotels in downtown Houston are:

- Hilton Americas Convention Center Hotel

- Marriott Marquis Houston

- Four Seasons Hotel and Residences

- JW Marriott Downtown Houston[158]

- Doubletree Hotel Downtown Houston

- Hyatt Regency Houston, which features a revolving restaurant, the Spindletop, located on the hotel's 30th floor.[159]

- The Whitehall

- Club Quarters Hotel

- Courtyard Houston Downtown (Marriott)

- Residence Inn Marriott

- Westin Hotel

- SpringHill Suites Marriott

- Hotel Alessandra

Boutique hotels include:

- The Lancaster

- Magnolia Hotel

- Hotel Icon (Marriott)

- The Sam Houston Hotel

Retail and restaurants

[edit]

The Shops in Houston Center, located within the Houston Center complex, is an enclosed shopping mall. A few blocks away, GreenStreet is an open-air shopping center. The Houston Downtown Tunnel System is also home to many shops and restaurants. Several restaurants in Downtown Houston are in the Tunnel system, only open during working hours.[citation needed]

Katharine Shilcutt of the Houston Press said in 2012 that because of the Houston tunnel system taking traffic during the daytime and many office workers leaving for suburbs at night, many street level restaurants in Downtown Houston have difficulty operating. She added that the popularity of business-related lunches and dinners resulted in steakhouses in Downtown becoming successful.[160]

Fitness centers

[edit]Downtown hosts a branch of the YMCA, featuring a center for teenagers, a wellness center for females, a child watch area, a community meeting space, a chapel, group exercise rooms, and a racquetball court.[161] The Downtown YMCA provided dormitory space beginning in 1908, and continued to do so in its 1941 building, but the new YMCA to open in 2010 was not to have any. The current branch had a projected cost of $55 million.[162]

Artwork

[edit]In 2018 the street artist Dual made a mural representing Produce Row, which was a group of produce businesses on Commerce Street, on the Main & Co. building; at the time the area was in the first ward.[163]

Media

[edit]The Houston Chronicle, the citywide newspaper, previously had its headquarters in Downtown, but has since relocated c. 2014.[164] Beginning in 1998,[165] Houston Press headquarters was located in Downtown,[166] in the former Gillman Pontiac dealership building.[167] On the weekend after Friday October 25, 2013, the Houston Press was scheduled to move to its new offices in Midtown Houston.[165]

The magazine Houston Downtown was a Downtown-oriented magazine published by Rosie Walker.[168] Most area residents called it the "Downtowner." Walker was originally an office worker in Downtown Houston who was upset that she had learned of events occurring in Downtown Houston after they had already occurred. Walker said "Several people in our office decided to start a newsletter. It sort of expanded throughout our company and throughout our building."[169] It had been published for 14 years. In 1991 the business had paid off its debts. Walker decided not to take out loans to update her equipment and printing processes and instead closed the magazine during that year.[168]

The Downtown, Inc./Downtown Voice was another Downtown-related magazine. Kevin Clear of the Creneau Media Group planned to establish a magazine about Downtown Houston that would be published by Creneau. In January 1990 his company had developed a business plan aimed towards competing with Houston Downtown magazine. Houston Downtown was closed before Clear could develop a new magazine. Clear said "I hate to say we danced on their grave, but we weren't unhappy about the way things turned out."[168] Clear planned to introduce his magazine in May 1991. As of January 1991 he had not decided on a name for the magazine.[168] Elise Perachio became the editor of the magazine, which was ultimately named Downtown, Inc.[170] On August 1, 1994, the magazine, then called Downtown Voice, was sold to company Media Ink.[171]

Regional sports network AT&T SportsNet Southwest is headquartered in Downtown at GreenStreet.[172]

Transportation

[edit]

The Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO) operates Houston's public transportation systems. Downtown lies at the convergence of the three lines of Houston's light rail system, known as METRORail. The Red Line, which runs along Main Street, contains the following stations (from south to north): Downtown Transit Center, Bell, Main Street Square, Preston, and UH–Downtown.[173] The Southeast/Purple Line and East End/Green Lines stop at the Central, Convention District, and Theater District stations.

METRO operates many bus lines through Downtown.[174] Greenlink, a free-to-ride circulator shuttle, follows a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) circular route around the district. Greenlink is the successor to a trolley-style free-to-ride bus service which carried over 10,000 riders each day on five different routes prior to its disbandment in 2005.[175]

Taxicabs can be hailed from the street, at one of 21 taxi stands, or at various hotels. Taxi trips within Downtown have a flat rate of US$6, mandated by the city.[176] Uber operates within the city and surrounding areas.

Education

[edit]

One Main Building (formerly the Merchants and Manufacturers Building)

Colleges and universities

[edit]The University of Houston–Downtown (UHD) is a four-year state university, located at the northern-end of Downtown. Founded in 1974, it is one of four separate and distinct institutions in the University of Houston System. UHD has an enrollment of 14,255 students—making it the 15th largest public university in Texas and the second-largest university in the Houston area.[177]

The South Texas College of Law is a private law school located within Downtown and is one of three law schools in Houston.[178]

Downtown is within the Houston Community College System, and it is in close proximity to the Central Campus in Midtown.[179][180]

Primary and secondary education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]

The grade-school children of Downtown are served by the Houston Independent School District (HISD).

One public K-8 school, an HISD-affiliated charter school called Young Scholars Academy for Excellence (Y.S.A.F.E.), is in Downtown.[181] It was established on May 15, 1996, by Kenneth and Anella Coleman.[182] HISD's High School for the Performing and Visual Arts (HSPVA), a public magnet high school, broke ground on a new downtown campus in 2014,[183] and classes began there in 2019, replacing HSPVA's previous Montrose-area campus.[184]

Three public district elementary schools have zoning boundaries that extend to areas of Downtown with residential areas; they are:

- Bruce Elementary School (in the Fifth Ward)[185]

- Crockett Elementary School (northwest of Downtown)[186]

- Gregory-Lincoln Education Center[187] (in the Fourth Ward)

Gregory Lincoln Education Center[188] (in the Fourth Ward) takes most of Downtown's students at the middle school level. Marshall Middle School[189] (in Northside) takes students at the middle school level from a small section of northern Downtown. Northside High School (formerly Jefferson Davis High School),[190] also in Northside, takes students from almost all of Downtown at the high school level. Heights High School (formerly Reagan High School),[191] in the Houston Heights, take students in the high school level from a small section of northwest Downtown.

History of public schools

[edit]The block bounded by Austin, Capitol, Caroline, and Rusk held schools for many years. Houston Academy was established there in the 1850s. In 1894 the groundbreaking for Central High School occurred there. Central burned down in March 1919. In 1921 Sam Houston High School opened at the site.[192] The current Sam Houston building in the Northside opened in 1955.[193] The previous building became the administrative headquarters of the Houston Independent School District. By the early 1970s HISD moved its headquarters out of the building, which was demolished. As of 2011 a parking lot occupies the former school lot; a state historical marker is located at the lot.[192]

Booker T. Washington High School's first location, 303 West Dallas, served as the school's location from 1893 to 1959, when it moved to the north. Lockett Junior High School was established in the former Washington campus and closed in 1968.[194]

Anson Jones Elementary School served a portion of Downtown until its closing in Summer 2006.[194][195] Anson Jones opened in 1892 as the Elysian Street School; its first campus was destroyed in a fire, and that was replaced in 1893 with a three-story building at 914 Elysian in what is now Downtown. It was named after Anson Jones in 1902. In the 1950s many students resided in Clayton Homes and the students were majority Hispanic and Latino. In 1962 it had 609 students. Anson Jones moved to a new campus in the Second Ward in 1966, and its original campus in Downtown was demolished.[196]

Brock Elementary School served a portion of Downtown until its closing in Summer 2006 and repurposing as an early childhood center; its boundary was transferred to Crockett Elementary.[194][197] Before the start of the 2009–2010 school year J. Will Jones was consolidated into Blackshear Elementary School, a campus in the Third Ward.[198][199] During its final year of enrollment J. Will Jones had more students than Blackshear. Many J. Will Jones parents referred to Blackshear as "that prison school" and said that they will not send their children to Blackshear.[200] By Spring 2011 Atherton Elementary School and E.O. Smith were consolidated with a new K-5 campus in the Atherton site.[201] Middle school students in Downtown were rezoned to Gregory-Lincoln.[188][202]

As part of rezoning for the 2014–2015 school year, in Downtown all areas previously under the Blackshear attendance zone and many areas in the Bruce attendance zone were rezoned to Gregory-Lincoln K-8.[203]

Private schools

[edit]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston oversees the Incarnate Word Academy, a Catholic all-girls school founded in 1873 and the only high school located in Downtown until the opening of the new HSPVA campus in 2017.[204] Trinity Lutheran School, a PreK-8 Lutheran School, is located at 800 Houston Avenue, northwest of and in close proximity to Downtown. Its early childhood center is located at 1316 Washington Avenue, near the K-8 center and in proximity to Downtown.[179][205]

On September 27, 1897, a school in the two-story annex to the Sacred Heart Parish, staffed by Dominican sisters, opened with 28 enrolled students.[206] St. Thomas College (now known as St. Thomas High School) opened in Downtown in 1900.[207] In 1902 the parish bought a building used by St. Thomas and moved it from Franklin Street at Crawford Street to Pierce Street and Fannin Street. In 1905 the parish sought and received approval from the state to start a high school; in January 1907 Saint Agnes Academy, outside of Downtown, opened and high school students were transferred to St. Agnes. In 1911 the former school building, known as the Green House, was demolished and replaced by a church building. In 1922 the existing Sacred Heart School building opened; the parish spent $52,800 ($961,000 in today's currency) to build the building.[206] St. Thomas moved to its current location, outside of Downtown, in 1940.[207] The Sacred Heart School provided Catholic elementary education for 70 years until its closing in May 1967 after declining enrollment and increased operation costs. As of 2009 the former Sacred Heart building houses the diocese's parish religious education program.[206]

Public libraries

[edit]

Houston Public Library has the Central Library in Houston. It consists of two buildings, including the Jesse H. Jones Building, which contains the bulk of the library facilities, and the Julia Ideson Building, which contains archives, manuscripts, and the Texas and Local History Department.[208]

Houston's first public library facility opened on March 2, 1904.[209] The Ideson building opened in 1926, replacing the previous building. The Jesse H. Jones Building opened in 1976 and received its current name in 1989.[210] The Jones Building closed for renovations on Monday April 3, 2006.[211] It reopened May 31, 2008.[212] After renovations began the Houston Public Library headquarters moved from the Jones Building to the Marston Building in Neartown Houston.[213][214][215]

In addition, HPL operates the HPL Express Discovery Green at 1300 McKinney R2, adjacent to Discovery Green Park.[216][217] HPL Express facilities are library facilities located in existing buildings.[218] The library opened in 2008.[219]

Harris County Public Library operates the Law Library,[220] located on the first floor of Congress Plaza.[221]

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in downtown Houston, Texas

- Architecture of Houston

- Houston Downtown Tunnel System

- Houston Theater District

- Midtown Houston

- Greenway Plaza, Houston

- Neartown Houston

- Uptown Houston

- Greenspoint, Houston

- Westchase, Houston

- Memorial City, Houston

- Houston Energy Corridor

- Central business district

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Downtown at a Glance: June 2017" (PDF). Downtown District. June 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ "Downtown Houston Block Numbering (HCAD)" (PDF). Downtown District. January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Fact Sheet." () Downtown Houston Management District. Retrieved on April 7, 2009.

- ^ "Downtown Districts." Downtown Houston. Retrieved on June 11, 2016

- ^ a b "Eclectic variety of lively districts comprise downtown Houston". Houston Business Journal. November 17, 2006. Retrieved on March 11, 2010.

- ^ Livingston, Ronald Howard (June 15, 2010) [June 1, 1995]. "Parrott, Thomas F. L." Handbook of Texas. TSHA. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Protected Landmark Designation Report – Stuart Building" (PDF). City of Houston. March 21, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Glass, James L. (1994). "The Original Book of Sales of Lots in the Houston Town Company from 1836 Forward" (PDF). The Houston Review. 16: 167–194 – via Houston History Magazine.

- ^ a b c d e Kirkland, Kate Sayan (2009). The Hogg Family and Houston: Philanthropy and the Civic Ideal. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780292748460.

- ^ Theis, David (2010). "Back to the Future" (PDF). Market Square Park. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Chapman, Betty Trapp (Fall 2010). "A System of Government Where Business Ruled" (PDF). Houston History Magazine. 8: 29–33.

- ^ a b c Sturrock, Sidonie (Spring 2015). "Uncovering the Story of Quality Hill, Houston's First Elite Residential Neighborhood: A Detective on the Case" (PDF). Houston History Magazine. 12–2: 7–12.

- ^ George, Cindy (September 4, 2016). "Frost Town offers a peek into the past". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Baron, Steven (1994). "Streetcars and the Growth of Houston" (PDF). The Houston Review. 16: 67–100.

- ^ Information from Emporis[usurped]

- ^ Bivins, Ralph. "ON DECK/The stadium vote/Stadium gives hope to downtown landowners Archived 2012-06-17 at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. Sunday September 29, 1996. A1. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "Study Area 11 Archived May 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Accessed October 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c Barna, Joel Warren. "Filling the Doughnut." Cite 42. Summer/Fall (northern hemisphere) 1998. Published in: Scardino, Barrie and Bruce Webb. Ephemeral City. University of Texas Press, 2003. Google Books Page 73. ISBN 0-292-70187-X, 9780292701878.

- ^ a b Bivins, Ralph. "SURVIVAL OF THE NEWEST / OCCUPANCY DOWNTOWN TUMBLING, BUT THREE TOWERS DEFY TREND." Houston Chronicle. Sunday July 27, 2003. Business 1. Retrieved on November 11, 2009.

- ^ Bivins, Ralph. "Houston office occupancy increases/Survey: 3.1 million square feet of space absorbed last year." Houston Chronicle. Tuesday January 17, 1989. Retrieved on August 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Bivins, Ralph. "Downtown to get 27-story tower / Opening planned for 2002." Houston Chronicle. Thursday August 10, 2000. Business 1. Retrieved on November 12, 2009.

- ^ Nichols, Bruce. "The Selling of a City." The Dallas Morning News. June 7, 1987. Retrieved on November 11, 2009.

- ^ Rutledge, Tanya. "Continental picks Cullen Center as destination for downtown HQ." Houston Business Journal. Friday January 31, 1997. Retrieved on August 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Zehr, Leonard. "TrizecHahn nabs U.S. leasing deal Continental Airlines enticed to move head office to downtown Houston from suburbs." The Globe and Mail. September 11, 1997. Report on Business B7. Retrieved from LexisNexis on April 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Wray, Dianna (June 25, 2019). "How Downtown Houston Went from Barren to Bustling". Houstonia. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Sarnoff, Nancy. "Cullen Center snags new leases." Houston Business Journal. Wednesday February 18, 2004. Retrieved on November 11, 2009.

- ^ Barna, Joel Warren. "Filling the Doughnut." Cite 42. Summer/Fall (northern hemisphere) 1998. Published in: Scardino, Barrie and Bruce Webb. Ephemeral City. University of Texas Press, 2003. Google Books Page 72. ISBN 0-292-70187-X, 9780292701878.

- ^ Kudela & Weinheimer. "Award Winning Landscape Architecture Firm Creates 'High-Rise Oasis' in Downtown Houston". Press Release. PR Newswire. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ^ "Microsoft Word – General Release.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 29, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ "Cotswold". Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ "Downtown Houston Development/Project List" (). Greater Houston Partnership. Retrieved on April 23, 2010.

- ^ "Phoenicia Downtown Ribbon Cutting". Retrieved June 16, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Shilcutt, Katharine. "Lebanese Queso and More at the Fabulous New Phoenicia Downtown Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Press. Thursday November 17, 2011. Retrieved on November 19, 2011.

- ^ Luck, Marissa (May 19, 2022). "In downtown Houston, a rebound is underway, but where are the full-time office workers?". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Luck, Marissa (May 20, 2022). "Houstonians are out to play, fueling a revival for downtown's hotels and venues". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "7 dead in Houston area after storms and 100-mph winds". NBC News. May 18, 2024. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Fallows, James (July 1, 1985). "Houston: A Permanent Boomtown". The Atlantic. ISSN 2151-9463. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Wray, Dianna (June 25, 2019). "How Downtown Houston Went from Barren to Bustling". Houstonia Magazine. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ "1500 Louisiana St". CrediFi. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Architecture of Enron Center South – Houston, Texas, United States of America[usurped]

- ^ Microsoft Word – 02-FactSheet .doc

- ^ "Why downtown?" (PDF). www.downtownhouston.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "No. 61 Super Neighborhood Assessment" (PDF). City of Houston. June 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ "No. 61 Super Neighborhood Assessment" (PDF). City of Houston. November 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ "Census 2000: Demographic Data by Super Neighborhood DOWNTOWN AREA #61". City of Houston. Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2021. - Percentages were from the 2017 document.

- ^ "1Q 2016 Market Report: Houston Office Market" (PDF). Cresa. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Sarnoff, Nancy (November 22, 2016). "Report: Houston has some of the priciest office space in U.S." Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Feser, Katherine (November 19, 2015). "Louisiana Street is Houston's most expensive, report says". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Office." () Uptown Houston. Retrieved on January 18, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived 2008-12-22 at the Wayback Machine." Dynegy. Retrieved on December 10, 2008.

- ^ "Locations Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." KBR. Retrieved on January 13, 2009.

- ^ "Locations & Office Hours Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine." KBR Heritage Federal Credit Union. Retrieved on December 10, 2008.

- ^ "Baker Botts hires corporate partner." Austin Business Journal. Wednesday January 21, 2004. Retrieved on August 25, 2010.

- ^ "Houston, Texas Archived August 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Baker Botts. Retrieved on August 25, 2010. "One Shell Plaza 910 Louisiana Street | Houston | Texas..."

- ^ "Locations." Bracewell. Retrieved on May 21, 2022.

- ^ "Corporate: Driving Directions." Total Petrochemicals USA. Retrieved on April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Gas & Power Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine." Total S.A. Retrieved on January 25, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Information." CenterPoint Energy. Retrieved on January 14, 2009.

- ^ "CenterPoint Energy Tower Archived July 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." Berger Iron Works. Retrieved on January 14, 2009.

- ^ Selden, Jonathan. "Law firms in Austin help Houston offices." Austin Business Journal. Thursday September 22, 2005. Retrieved on May 5, 2010. "At Vinson & Elkins LLP, the Austin office is accommodating evacuated attorneys from the Houston headquarters as well as some clients, says Don Wood, administrative partner."

- ^ "Houston." Vinson & Elkins. Retrieved on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived August 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine." Waste Management, Inc. Retrieved on January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Corporate Archived March 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." El Paso Corporation. Retrieved on January 16, 2009.

- ^ "Welcome to Plains All American Pipeline!" Plains All American Pipeline. Retrieved on December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived 2009-11-25 at the Wayback Machine." Enterprise GP Holdings. Retrieved on December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Directory Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine." EOG Resources. Retrieved on December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Headquarters Location Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine." Continental Airlines. Retrieved on December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Air Transportation ." Opportunity Houston. Retrieved on December 10, 2008.

- ^ "Expressjet.com Terms, Conditions, And Notices." ExpressJet Airlines. June 8, 2003. Retrieved on May 19, 2009.

- ^ "Company History 1991 to 2000 Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine." Continental Airlines. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ^ Boisseau, Charles. "Airline confirms relocation/Continental moving offices downtown." Houston Chronicle. Wednesday September 3, 1997. Business 1. Retrieved on August 23, 2009.

- ^ Bivins, Ralph. "Hotels see high occupancy, rates Archived 2012-06-17 at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. Friday September 26, 1997. Business 1. Retrieved on August 23, 2009.

- ^ Dawson, Jennifer. "Continental renews lease, decides to stay downtown." Houston Business Journal. Friday September 19, 2008. Retrieved on November 11, 2009.

- ^ Moreno, Jenalia. "CEO aims for smooth landing in United-Continental merge." Houston Chronicle. Sunday September 25, 2011. 2. Retrieved on October 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Sarnoff, Nancy. "Historic downtown Chase building sold." Houston Chronicle. February 12, 2010. Retrieved on February 24, 2010.

- ^ "Houston Office & Refining Operations." LyondellBasell. Retrieved on February 5, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Hess Archived February 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Hess Corporation. Retrieved on February 9, 2009.

- ^ "Central Houston Inc". Business Development. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "contact us business headquarters." ExxonMobil. Retrieved on January 26, 2009.

- ^ "Houston." Qatar Airways. Retrieved on February 9, 2009.

- ^ Fact Sheet June 2007 Archived July 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Pavilions. Retrieved on January 13, 2009.

- ^ "Retail Leasing[permanent dead link]." Houston Pavilions. Retrieved on January 13, 2009.

- ^ "Spearhead Pipeline Expansion Project Open Season Is Now Closed Archived February 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Enbridge. Retrieved on December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Offices." KPMG. Retrieved on December 17, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Information Archived December 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Mayer Brown. Retrieved on December 17, 2009.

- ^ "Company News; Enron Plans to Sell Its Headquarters in Houston." The New York Times. Thursday August 21, 2003. Retrieved on October 20, 2009.

- ^ Colley, Jenna. "Federated to cut jobs at Foley's distribution center." Houston Business Journal. Friday April 14, 2006. Retrieved on October 20, 2009.

- ^ "0000950129-97-001088.txt : 19970320" (Archive). Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved on April 14, 2014. "Houston Industries Incorporated and Houston Lighting & Power Company Houston Industries Plaza 1111 Louisiana, 47th Floor Houston, TX 77002-5231"

- ^ "Office Location." Halliburton. Retrieved on January 13, 2009.

- ^ Sarnoff, Nancy. "Downtown up, Westchase down as Halliburton postpones project." Houston Business Journal. Friday December 21, 2009. Retrieved on November 11, 2009.

- ^ Clanton, Brett. "Halliburton to consolidate in 2 locations." Houston Chronicle. April 3, 2009. Retrieved on April 3, 2009.

- ^ City of Houston, Council District Maps, District H Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Retrieved on November 5, 2011.

- ^ City of Houston, Council District Maps, District I Archived September 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Retrieved on November 5, 2011.

- ^ "City Council." City of Houston. Retrieved on October 25, 2015.

- ^ "Beat Map Archived October 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Police Department. Retrieved on April 5, 2010.

- ^ "Ceremony held for renaming of HPD headquarters in honor of retired officer." Retrieved on October 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Fire Stations." City of Houston. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ a b "Fire Station 8 Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Retrieved on May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Fire Station 3 Archived 2010-05-29 at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Retrieved on May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Fire Station 5 Archived May 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Retrieved on May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Fire Station 2 Archived May 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." City of Houston. Retrieved on May 8, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived February 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Downtown Management District. Retrieved on April 7, 2009.

- ^ "Maps: All Precincts Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Harris County Precinct 3. Retrieved on November 22, 2008.

- ^ "Harris County Precinct One > Home". hcp1.net. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Harris County Commissioner Precinct 2". www.hcp2.com. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Courthouse Annexes Archived 2010-04-22 at the Wayback Machine." Harris County Precinct Two. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ^ "Harris County Courts". www.ccl.hctx.net. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Harris County District Courts". www.justex.net. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Jury Service". www.hcdistrictclerk.com. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ The 1200 Jail Archived February 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Harris County, Texas. Accessed September 12, 2008.

- ^ "The 1307 Jail Archived 2008-10-03 at the Wayback Machine." Harris County, Texas. Accessed September 12, 2008.

- ^ "The 701 Jail Archived 2008-09-18 at the Wayback Machine." Harris County, Texas. Accessed September 12, 2008.

- ^ a b "Clinic/Emergency/Registration Center Directory By ZIP Code". Harris County Hospital District. November 19, 2001. Archived from the original on November 19, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2021. - See ZIP codes 77002, 77003, 77007, and 77010. See this map for relevant ZIP codes.

- ^ "Gulfgate Health Center" (Archive). Harris County Hospital District. Accessed October 17, 2008.

- ^ Representatives, George Hewitt - Texas House of. "Texas House of Representatives". house.texas.gov. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ Representatives, George Hewitt - Texas House of. "Texas House of Representatives". house.texas.gov. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "The Texas State Senate: District 13". www.senate.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on August 3, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Kegans (HM) Archived September 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Accessed September 12, 2008.

- ^ Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Turner Publishing Company, 2004. 51. ISBN 1-56311-964-1, ISBN 978-1-56311-964-4.

- ^ "SOUTH TEXAS (XM) Archived 2008-08-21 at the Wayback Machine." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Accessed September 12, 2008.

- ^ "TJB | 1st COA | Contact Us". www.txcourts.gov. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "TJB | 14th COA | Contact Us". www.txcourts.gov. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ nationalatlas.gov website Archived October 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Representative Sheila Jackson Lee". Representative Sheila Jackson Lee. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ Shen, Michelle (July 20, 2024). "Sheila Jackson Lee, long-serving Democratic congresswoman and advocate for Black Americans, dies at 74 | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ "Texas Democratic Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee has died". USA TODAY. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ "Post Office Location – HOUSTON." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on December 4, 2008.

- ^ Hernandez, Pat. "Downtown Houston Post Office Closes." Houston Public Media. May 15, 2015. Retrieved on October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Schuetz, R.A.; Feser, Katherine (March 19, 2021). "Redesigned former post office wants to put new stamp on Houston". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "Downtown post office, designed by Astrodome architects, sets closing date". CultureMap Houston. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ reporter, miya shay, eyewitness news (December 17, 2014). "What will closure of downtown post office mean?". ABC13 Houston. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Get Your Stamps There While You Still Can Downtown Barbara Jordan Post Office on Franklin St. Will Close Forever on May 15th." Swamplot. May 6, 2015. Retrieved on October 30, 2016.

- ^ "1500 Hadley St. Replacement for Houston's Shuttering Downtown Post Office Is Actually Somewhat Close to Downtown." Swamplot. Retrieved on October 30, 2016.

- ^ "Best Post Office – 2010 U.S. Post Office on Franklin Street." Houston Press. Retrieved on December 12, 2010.

- ^ Najaro, Ileana (October 6, 2016). "Events draw attention as former post office undergoes transformation". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Weisman, Laura. "Nine Houston post offices marked for closure (with poll) Archived October 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. July 26, 2011. Retrieved on July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Mickey Leland Federal Building Archived 2009-05-09 at the Wayback Machine." U.S. General Services Administration. Retrieved on April 16, 2009.

- ^ "FR Doc E9-24240." Federal Register at U.S. Government Printing Office. October 8, 2009. Volume 74, Number 194. Retrieved on March 31, 2010.

- ^ "FDC Houston." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Houston Archived 2008-11-23 at the Wayback Machine." Consulate-General of the United Kingdom. Retrieved on December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Contact Us." Consulate-General of Japan in Houston. Retrieved on December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Visa Desk." Consulate General of Switzerland in Houston. September 5, 2004.

- ^ "Essence of Switzerland Archived 2008-09-14 at the Wayback Machine." Paul Scherrer Institute. Retrieved on December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Location." Consulate General of Switzerland in Houston. October 23, 2002.

- ^ Hodge, Shelby. "MIXERS, ELIXIRS AND IMAX SUMMER SOCIALS / Party animals drink with the dinosaurs." Houston Chronicle. Star 3. June 22, 2006. Retrieved on January 10, 2009.

- ^ "'New' Market Square Park to be unveiled".

- ^ Shauk, Zain (September 11, 2010). "Remembering 9/11 Victim's legacy grows at Lauren's Garden in Houston". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Features." Discovery Green Park. Retrieved on January 27, 2009.

- ^ Kaplan, David (May 3, 2013). "Discovery Green keeps giving city a fresh image". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "History of Discovery Green". Discovery Green Conservancy. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ "Main Street Square". www.downtownhouston.org. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Root Memorial Square". www.downtownhouston.org. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Quebedeaux Park." Harris County. Retrieved on January 3, 2009.

- ^ "Quebedeaux Park" Layout. Harris County. Retrieved on January 3, 2009.

- ^ Scherer, Jasper (March 11, 2021). "Construction begins on 'Trebly Park' in south downtown Houston". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 29, 2021. - Alternate link

- ^ Smith, Tierra (March 13, 2021). "GALLERY: Trebly Park breaks ground in downtown Houston". KPRC. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "The New Avenida". www.houstonconventiondistrict.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ^ "806 Main St". CrediFI. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ "Spindletop Restaurant Houston". www.hyatt.com. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ Shilcutt, Katharine. "Rest(aurants) in Peace: Notable Closings of 2012." Houston Press. Monday December 10, 2012. 3. Retrieved on March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Work begins on Tellepsen Family YMCA Archived 2012-06-17 at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. January 14, 2009. Retrieved on September 21, 2009.

- ^ Dooley, Tara. "It's been fun to stay at the Y Archived 2012-06-17 at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. August 22, 2008. Retrieved on September 21, 2009.

- ^ Hlavaty, Craig (September 24, 2018). "New Houston mural honors downtown's 'Produce Row' roots". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ "Houston Chronicle announces relocation and renovation". Houston Chronicle. July 21, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Garza, Abrahán. "Spaced City The Houston Press Moves to New Digs, From Downtown to Midtown." Houston Press. October 25, 2013. p. 1 (Archive). Retrieved on October 25, 2013.

- ^ "About Us" Archived April 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Houston Press. Retrieved on August 7, 2009.

- ^ Garza, Abrahán. "Old Houston Photos Mashed with Modern Houston, Part 2." Houston Press. Monday May 7, 2012. 1 Archived May 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on May 7, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Hassell, Greg. "PUBLISH OR PERISH/Small magazines born every year with big dreams." Houston Chronicle. Monday January 28, 1991. Business 1. Retrieved on October 14, 2012.

- ^ Pope, Tara Parker. "Last issue for Downtown." Houston Chronicle. Saturday January 19, 1991. A35. Retrieved on October 14, 2012.

- ^ Staff. "People in business." Houston Chronicle. Sunday November 10, 1991. Business 8. Retrieved on October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Houston group buys neighborhood magazines from New Mexico owner. (Media ink; Creneau Media Group Inc.)" Houston Business Journal. August 12, 1994. Retrieved on October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Contact Us". ROOT SPORTS. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ "Rail Map & Schedule Archived 2008-12-17 at the Wayback Machine." Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County, Texas. Retrieved on December 10, 2008.

- ^ "Central Business District/Downtown Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine." Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County, Texas. Retrieved on December 10, 2008.