Frame-dragging

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

| General relativity |

|---|

|

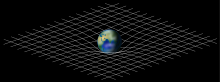

Frame-dragging is an effect on spacetime, predicted by Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, that is due to non-static stationary distributions of mass–energy. A stationary field is one that is in a steady state, but the masses causing that field may be non-static — rotating, for instance. More generally, the subject that deals with the effects caused by mass–energy currents is known as gravitoelectromagnetism, which is analogous to the magnetism of classical electromagnetism.

The first frame-dragging effect was derived in 1918, in the framework of general relativity, by the Austrian physicists Josef Lense and Hans Thirring, and is also known as the Lense–Thirring effect.[1][2][3] They predicted that the rotation of a massive object would distort the spacetime metric, making the orbit of a nearby test particle precess. This does not happen in Newtonian mechanics for which the gravitational field of a body depends only on its mass, not on its rotation. The Lense–Thirring effect is very small – about one part in a few trillion. To detect it, it is necessary to examine a very massive object, or build an instrument that is very sensitive.

In 2015, new general-relativistic extensions of Newtonian rotation laws were formulated to describe geometric dragging of frames which incorporates a newly discovered antidragging effect.[4]

Effects

Rotational frame-dragging (the Lense–Thirring effect) appears in the general principle of relativity and similar theories in the vicinity of rotating massive objects. Under the Lense–Thirring effect, the frame of reference in which a clock ticks the fastest is one which is revolving around the object as viewed by a distant observer. This also means that light traveling in the direction of rotation of the object will move past the massive object faster than light moving against the rotation, as seen by a distant observer. It is now the best known frame-dragging effect, partly thanks to the Gravity Probe B experiment. Qualitatively, frame-dragging can be viewed as the gravitational analog of electromagnetic induction.

Also, an inner region is dragged more than an outer region. This produces interesting locally rotating frames. For example, imagine that a north–south-oriented ice skater, in orbit over the equator of a rotating black hole and rotationally at rest with respect to the stars, extends her arms. The arm extended toward the black hole will be "torqued" spinward due to gravitomagnetic induction ("torqued" is in quotes because gravitational effects are not considered "forces" under GR). Likewise the arm extended away from the black hole will be torqued anti-spinward. She will therefore be rotationally sped up, in a counter-rotating sense to the black hole. This is the opposite of what happens in everyday experience. There exists a particular rotation rate that, should she be initially rotating at that rate when she extends her arms, inertial effects and frame-dragging effects will balance and her rate of rotation will not change. Due to the equivalence principle, gravitational effects are locally indistinguishable from inertial effects, so this rotation rate, at which when she extends her arms nothing happens, is her local reference for non-rotation. This frame is rotating with respect to the fixed stars and counter-rotating with respect to the black hole. This effect is analogous to the hyperfine structure in atomic spectra due to nuclear spin. A useful metaphor is a planetary gear system with the black hole being the sun gear, the ice skater being a planetary gear and the outside universe being the ring gear. See Mach's principle.

Another interesting consequence is that, for an object constrained in an equatorial orbit, but not in freefall, it weighs more if orbiting anti-spinward, and less if orbiting spinward. For example, in a suspended equatorial bowling alley, a bowling ball rolled anti-spinward would weigh more than the same ball rolled in a spinward direction. Note, frame dragging will neither accelerate nor slow down the bowling ball in either direction. It is not a "viscosity". Similarly, a stationary plumb-bob suspended over the rotating object will not list. It will hang vertically. If it starts to fall, induction will push it in the spinward direction. However, if a "yoyo" plumb-bob (with axis perpendicular to the equatorial plane) is slowly lowered, over the equator, toward the static limit, the yoyo will spin up in a counter rotating direction. Curiously, any denizens inside the yoyo will not feel any torque and will not experience any felt change in angular momentum.

Linear frame dragging is the similarly inevitable result of the general principle of relativity, applied to linear momentum. Although it arguably has equal theoretical legitimacy to the "rotational" effect, the difficulty of obtaining an experimental verification of the effect means that it receives much less discussion and is often omitted from articles on frame-dragging (but see Einstein, 1921).[5]

Static mass increase is a third effect noted by Einstein in the same paper.[6] The effect is an increase in inertia of a body when other masses are placed nearby. While not strictly a frame dragging effect (the term frame dragging is not used by Einstein), it is demonstrated by Einstein that it derives from the same equation of general relativity. It is also a tiny effect that is difficult to confirm experimentally.

Experimental tests

In 1976 Van Patten and Everitt[7][8] proposed to implement a dedicated mission aimed to measure the Lense–Thirring node precession of a pair of counter-orbiting spacecraft to be placed in terrestrial polar orbits with drag-free apparatus. A somewhat equivalent, less expensive version of such an idea was put forth in 1986 by Ciufolini[9] who proposed to launch a passive, geodetic satellite in an orbit identical to that of the LAGEOS satellite, launched in 1976, apart from the orbital planes which should have been displaced by 180 degrees apart: the so-called butterfly configuration. The measurable quantity was, in this case, the sum of the nodes of LAGEOS and of the new spacecraft, later named LAGEOS III, LARES, WEBER-SAT.

Limiting the scope to the scenarios involving existing orbiting bodies, the first proposal to use the LAGEOS satellite and the Satellite Laser Ranging (SLR) technique to measure the Lense–Thirring effect dates to 1977–1978.[10] Tests started to be effectively performed by using the LAGEOS and LAGEOS II satellites in 1996,[11] according to a strategy[12] involving the use of a suitable combination of the nodes of both satellites and the perigee of LAGEOS II. The latest tests with the LAGEOS satellites have been performed in 2004–2006[13][14] by discarding the perigee of LAGEOS II and using a linear combination.[15] Recently, a comprehensive overview of the attempts to measure the Lense-Thirring effect with artificial satellites was published in the literature.[16] The overall accuracy reached in the tests with the LAGEOS satellites is subject to some controversy.[17][18][19]

The Gravity Probe B experiment[20][21] was a satellite-based mission by a Stanford group and NASA, used to experimentally measure another gravitomagnetic effect, the Schiff precession of a gyroscope,[22][23][24] to an expected 1% accuracy or better. Unfortunately such accuracy was not achieved. The first preliminary results released in April 2007 pointed towards an accuracy of[25] 256–128%, with the hope of reaching about 13% in December 2007.[26] In 2008 the Senior Review Report of the NASA Astrophysics Division Operating Missions stated that it was unlikely that the Gravity Probe B team will be able to reduce the errors to the level necessary to produce a convincing test of currently untested aspects of General Relativity (including frame-dragging).[27][28] On May 4, 2011, the Stanford-based analysis group and NASA announced the final report,[29] and in it the data from GP-B demonstrated the frame-dragging effect with an error of about 19 percent, and Einstein's predicted value was at the center of the confidence interval.[30][31]

NASA published claims of success in verification of frame dragging for the GRACE twin satellites[32] and Gravity Probe B,[33] both of which claims are still in public view. A research group in Italy,[34] USA, and UK also claimed success in verification of frame dragging with the Grace gravity model, published in a peer reviewed journal. All the claims include recommendations for further research at greater accuracy and other gravity models.

In the case of stars orbiting close to a spinning, supermassive black hole, frame dragging should cause the star's orbital plane to precess about the black hole spin axis. This effect should be detectable within the next few years via astrometric monitoring of stars at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.[35]

By comparing the rate of orbital precession of two stars on different orbits, it is possible in principle to test the no-hair theorems of general relativity, in addition to measuring the spin of the black hole.[36]

Astronomical evidence

Relativistic jets may provide evidence for the reality of frame-dragging. Gravitomagnetic forces produced by the Lense–Thirring effect (frame dragging) within the ergosphere of rotating black holes[37][38] combined with the energy extraction mechanism by Penrose[39] have been used to explain the observed properties of relativistic jets. The gravitomagnetic model developed by Reva Kay Williams predicts the observed high energy particles (~GeV) emitted by quasars and active galactic nuclei; the extraction of X-rays, γ-rays, and relativistic e−– e+ pairs; the collimated jets about the polar axis; and the asymmetrical formation of jets (relative to the orbital plane).

The Lense–Thirring effect has been observed in a binary system that consists of a massive white dwarf and a pulsar.[40]

Mathematical derivation

Frame-dragging may be illustrated most readily using the Kerr metric,[41][42] which describes the geometry of spacetime in the vicinity of a mass M rotating with angular momentum J, and Boyer–Lindquist coordinates (see the link for the transformation):

where rs is the Schwarzschild radius

and where the following shorthand variables have been introduced for brevity

In the non-relativistic limit where M (or, equivalently, rs) goes to zero, the Kerr metric becomes the orthogonal metric for the oblate spheroidal coordinates

We may rewrite the Kerr metric in the following form

This metric is equivalent to a co-rotating reference frame that is rotating with angular speed Ω that depends on both the radius r and the colatitude θ

In the plane of the equator this simplifies to:[43]

Thus, an inertial reference frame is entrained by the rotating central mass to participate in the latter's rotation; this is frame-dragging.

An extreme version of frame dragging occurs within the ergosphere of a rotating black hole. The Kerr metric has two surfaces on which it appears to be singular. The inner surface corresponds to a spherical event horizon similar to that observed in the Schwarzschild metric; this occurs at

where the purely radial component grr of the metric goes to infinity. The outer surface can be approximated by an oblate spheroid with lower spin parameters, and resembles a pumpkin-shape[44][45] with higher spin parameters. It touches the inner surface at the poles of the rotation axis, where the colatitude θ equals 0 or π; its radius in Boyer-Lindquist coordinates is defined by the formula

where the purely temporal component gtt of the metric changes sign from positive to negative. The space between these two surfaces is called the ergosphere. A moving particle experiences a positive proper time along its worldline, its path through spacetime. However, this is impossible within the ergosphere, where gtt is negative, unless the particle is co-rotating with the interior mass M with an angular speed at least of Ω. However, as seen above, frame-dragging occurs about every rotating mass and at every radius r and colatitude θ, not only within the ergosphere.

Lense–Thirring effect inside a rotating shell

The Lense–Thirring effect inside a rotating shell was taken by Albert Einstein as not just support for, but a vindication of Mach's principle, in a letter he wrote to Ernst Mach in 1913 (five years before Lense and Thirring's work, and two years before he had attained the final form of general relativity). A reproduction of the letter can be found in Misner, Thorne, Wheeler.[46] The general effect scaled up to cosmological distances, is still used as a support for Mach's principle.[46]

Inside a rotating spherical shell the acceleration due to the Lense–Thirring effect would be[47]

where the coefficients are

for MG ≪ Rc2 or more precisely,

The spacetime inside the rotating spherical shell will not be flat. A flat spacetime inside a rotating mass shell is possible if the shell is allowed to deviate from a precisely spherical shape and the mass density inside the shell is allowed to vary.[48]

See also

- Geodetic effect

- Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment

- Gravitomagnetism

- Mach's principle

- Broad iron K line

References

- ^ Thirring, H. (1918). "Über die Wirkung rotierender ferner Massen in der Einsteinschen Gravitationstheorie". Physikalische Zeitschrift. 19: 33. Bibcode:1918PhyZ...19...33T. [On the Effect of Rotating Distant Masses in Einstein's Theory of Gravitation]

- ^ Thirring, H. (1921). "Berichtigung zu meiner Arbeit: 'Über die Wirkung rotierender Massen in der Einsteinschen Gravitationstheorie'". Physikalische Zeitschrift. 22: 29. Bibcode:1921PhyZ...22...29T. [Correction to my paper "On the Effect of Rotating Distant Masses in Einstein's Theory of Gravitation"]

- ^ Lense, J.; Thirring, H. (1918). "Über den Einfluss der Eigenrotation der Zentralkörper auf die Bewegung der Planeten und Monde nach der Einsteinschen Gravitationstheorie". Physikalische Zeitschrift. 19: 156–163. Bibcode:1918PhyZ...19..156L. [On the Influence of the Proper Rotation of Central Bodies on the Motions of Planets and Moons According to Einstein's Theory of Gravitation]

- ^ Mach, Patryk; Malec, Edward (2015). "General-relativistic rotation laws in rotating fluid bodies". Physical Review D. 91 (12): 124053. arXiv:1501.04539. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..91l4053M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.91.124053. S2CID 118605334.

- ^ Einstein, A The Meaning of Relativity (contains transcripts of his 1921 Princeton lectures).

- ^ Einstein, A. (1987). The Meaning of Relativity. London: Chapman and Hall. pp. 95–96.

- ^ Van Patten, R. A.; Everitt, C. W. F. (1976). "Possible Experiment with Two Counter-Orbiting Drag-Free Satellites to Obtain a New Test of Einsteins's General Theory of Relativity and Improved Measurements in Geodesy". Physical Review Letters. 36 (12): 629–632. Bibcode:1976PhRvL..36..629V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.36.629. S2CID 120984879.

- ^ Van Patten, R. A.; Everitt, C. W. F. (1976). "A possible experiment with two counter-rotating drag-free satellites to obtain a new test of Einstein's general theory of relativity and improved measurements in geodesy". Celestial Mechanics. 13 (4): 429–447. Bibcode:1976CeMec..13..429V. doi:10.1007/BF01229096. S2CID 121577510.

- ^ Ciufolini, I. (1986). "Measurement of Lense–Thirring Drag on High-Altitude Laser-Ranged Artificial Satellites". Physical Review Letters. 56 (4): 278–281. Bibcode:1986PhRvL..56..278C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.56.278. PMID 10033146.

- ^ Cugusi, L.; Proverbio, E. (1978). "Relativistic Effects on the Motion of Earth's Artificial Satellites". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 69: 321. Bibcode:1978A&A....69..321C.

- ^ Ciufolini, I.; Lucchesi, D.; Vespe, F.; Mandiello, A. (1996). "Measurement of dragging of inertial frames and gravitomagnetic field using laser-ranged satellites". Il Nuovo Cimento A. 109 (5): 575–590. Bibcode:1996NCimA.109..575C. doi:10.1007/BF02731140. S2CID 124860519.

- ^ Ciufolini, I. (1996). "On a new method to measure the gravitomagnetic field using two orbiting satellites". Il Nuovo Cimento A. 109 (12): 1709–1720. Bibcode:1996NCimA.109.1709C. doi:10.1007/BF02773551. S2CID 120415056.

- ^ Ciufolini, I.; Pavlis, E. C. (2004). "A confirmation of the general relativistic prediction of the Lense–Thirring effect". Nature. 431 (7011): 958–960. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..958C. doi:10.1038/nature03007. PMID 15496915. S2CID 4423434.

- ^ Ciufolini, I.; Pavlis, E.C.; Peron, R. (2006). "Determination of frame-dragging using Earth gravity models from CHAMP and GRACE". New Astronomy. 11 (8): 527–550. Bibcode:2006NewA...11..527C. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2006.02.001.

- ^ Iorio, L.; Morea, A. (2004). "The Impact of the New Earth Gravity Models on the Measurement of the Lense-Thirring Effect". General Relativity and Gravitation. 36 (6): 1321–1333. arXiv:gr-qc/0304011. Bibcode:2004GReGr..36.1321I. doi:10.1023/B:GERG.0000022390.05674.99. S2CID 119098428.

- ^ Renzetti, G. (2013). "History of the attempts to measure orbital frame-dragging with artificial satellites". Central European Journal of Physics. 11 (5): 531–544. Bibcode:2013CEJPh..11..531R. doi:10.2478/s11534-013-0189-1.

- ^ Renzetti, G. (2014). "Some reflections on the Lageos frame-dragging experiment in view of recent data analyses". New Astronomy. 29: 25–27. Bibcode:2014NewA...29...25R. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2013.10.008.

- ^ Iorio, L.; Lichtenegger, H. I. M.; Ruggiero, M. L.; Corda, C. (2011). "Phenomenology of the Lense-Thirring effect in the solar system". Astrophysics and Space Science. 331 (2): 351–395. arXiv:1009.3225. Bibcode:2011Ap&SS.331..351I. doi:10.1007/s10509-010-0489-5. S2CID 119206212.

- ^ Ciufolini, I.; Paolozzi, A.; Pavlis, E. C.; Ries, J.; Koenig, R.; Matzner, R.; Sindoni, G.; Neumeyer, H. (2011). "Testing gravitational physics with satellite laser ranging". The European Physical Journal Plus. 126 (8): 72. Bibcode:2011EPJP..126...72C. doi:10.1140/epjp/i2011-11072-2. S2CID 122205903.

- ^ Everitt, C. W. F. The Gyroscope Experiment I. General Description and Analysis of Gyroscope Performance. In: Bertotti, B. (Ed.), Proc. Int. School Phys. "Enrico Fermi" Course LVI. New Academic Press, New York, pp. 331–360, 1974. Reprinted in: Ruffini, R. J.; Sigismondi, C. (Eds.), Nonlinear Gravitodynamics. The Lense–Thirring Effect. World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 439–468, 2003.

- ^ Everitt, C. W. F., et al., Gravity Probe B: Countdown to Launch. In: Laemmerzahl, C.; Everitt, C. W. F.; Hehl, F. W. (Eds.), Gyros, Clocks, Interferometers...: Testing Relativistic Gravity in Space. Springer, Berlin, pp. 52–82, 2001.

- ^ Pugh, G. E., Proposal for a Satellite Test of the Coriolis Prediction of General Relativity, WSEG, Research Memorandum No. 11, 1959. Reprinted in: Ruffini, R. J., Sigismondi, C. (Eds.), Nonlinear Gravitodynamics. The Lense–Thirring Effect. World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 414–426, 2003.

- ^ Schiff, L., On Experimental Tests of the General Theory of Relativity, American Journal of Physics, 28, pp. 340–343, 1960.

- ^ Ries, J. C.; Eanes, R. J.; Tapley, B. D.; Peterson, G. E. (2003). "Prospects for an improved Lense–Thirring test with SLR and the GRACE gravity mission" (PDF). Proceedings of the 13th International Laser Ranging Workshop NASA CP 2003.

- ^ Muhlfelder, B.; Mac Keiser, G.; and Turneaure, J., Gravity Probe B Experiment Error, poster L1.00027 presented at the American Physical Society (APS) meeting in Jacksonville, Florida, on 14–17 April 2007, 2007.

- ^ "StanfordNews 4/14/07" (PDF). einstein.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ "Report of the 2008 Senior Review of the Astrophysics Division Operating Missions". Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-21. Retrieved 2009-03-20. Report of the 2008 Senior Review of the Astrophysics Division Operating Missions, NASA

- ^ Hecht, Jeff. "Gravity Probe B scores 'F' in NASA review". New Scientist. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ "Gravity Probe B – MISSION STATUS".

- ^ "Gravity Probe B finally pays off". 2013-09-23. Archived from the original on 2012-09-30. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ^ "Gravity Probe B: Final results of a space experiment to test general relativity". Physical Review Letters. 2011-05-01. Archived from the original on 2012-05-20. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ^ Ramanujan, Krishna. "As World Turns it Drags Time and Space". NASA. Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Perrotto, Trent J. "Gravity Probe B". NASA. Washington, D.C.: NASA Headquarters. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Ciufolini, I.; Paolozzi, A.; Pavlis, E. C.; Koenig, R.; Ries, J.; Gurzadyan, V.; Matzner, R.; Penrose, R.; Sindoni, G.; Paris, C.; Khachatryan, H.; Mirzoyan, S. (2016). "A test of general relativity using the LARES and LAGEOS satellites and a GRACE Earth gravity model: Measurement of Earth's dragging of inertial frames". The European Physical Journal C. 76 (3): 120. arXiv:1603.09674. Bibcode:2016EPJC...76..120C. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-3961-8. PMC 4946852. PMID 27471430.

- ^ Merritt, D.; Alexander, T.; Mikkola, S.; Will, C. (2010). "Testing Properties of the Galactic Center Black Hole Using Stellar Orbits". Physical Review D. 81 (6): 062002. arXiv:0911.4718. Bibcode:2010PhRvD..81f2002M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.81.062002. S2CID 118646069.

- ^ Will, C. (2008). "Testing the General Relativistic "No-Hair" Theorems Using the Galactic Center Black Hole Sagittarius A*". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 674 (1): L25–L28. arXiv:0711.1677. Bibcode:2008ApJ...674L..25W. doi:10.1086/528847. S2CID 11685632.

- ^ Williams, R. K. (1995). "Extracting X rays, Ύ rays, and relativistic e−– e+ pairs from supermassive Kerr black holes using the Penrose mechanism". Physical Review D. 51 (10): 5387–5427. Bibcode:1995PhRvD..51.5387W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.51.5387. PMID 10018300.

- ^ Williams, R. K. (2004). "Collimated escaping vortical polar e−–e+ jets intrinsically produced by rotating black holes and Penrose processes". The Astrophysical Journal. 611 (2): 952–963. arXiv:astro-ph/0404135. Bibcode:2004ApJ...611..952W. doi:10.1086/422304. S2CID 1350543.

- ^ Penrose, R. (1969). "Gravitational collapse: The role of general relativity". Nuovo Cimento Rivista. 1 (Numero Speciale): 252–276. Bibcode:1969NCimR...1..252P.

- ^ Krishnan, V. Venkatraman; et al. (31 January 2020). "Lense–Thirring frame dragging induced by a fast-rotating white dwarf in a binary pulsar system". Science. 367 (5): 577–580. arXiv:2001.11405. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..577V. doi:10.1126/science.aax7007. PMID 32001656. S2CID 210966295.

- ^ Kerr, R. P. (1963). "Gravitational field of a spinning mass as an example of algebraically special metrics". Physical Review Letters. 11 (5): 237–238. Bibcode:1963PhRvL..11..237K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.11.237.

- ^ Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1975). The Classical Theory of Fields (Course of Theoretical Physics, Vol. 2) (revised 4th English ed.). New York: Pergamon Press. pp. 321–330. ISBN 978-0-08-018176-9.

- ^ Tartaglia, A. (2008). "Detection of the gravitometric clock effect". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 17 (4): 783–792. arXiv:gr-qc/9909006. Bibcode:2000CQGra..17..783T. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/17/4/304. S2CID 9356721.

- ^ a b Visser, Matt (2007). "The Kerr spacetime: A brief introduction". p. 35. arXiv:0706.0622v3 [gr-qc].

- ^ a b Blundell, Katherine Black Holes: A Very Short Introduction Google books, page 31

- ^ a b Misner, Thorne, Wheeler, Gravitation, Figure 21.5, page 544

- ^ Pfister, Herbert (2005). "On the history of the so-called Lense–Thirring effect". General Relativity and Gravitation. 39 (11): 1735–1748. Bibcode:2007GReGr..39.1735P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.4061. doi:10.1007/s10714-007-0521-4. S2CID 22593373.

- ^ Pfister, H.; et al. (1985). "Induction of correct centrifugal force in a rotating mass shell". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 2 (6): 909–918. Bibcode:1985CQGra...2..909P. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/2/6/015. S2CID 250883114.

Further reading

- Renzetti, G. (May 2013). "History of the attempts to measure orbital frame-dragging with artificial satellites". Central European Journal of Physics. 11 (5): 531–544. Bibcode:2013CEJPh..11..531R. doi:10.2478/s11534-013-0189-1.

- Ginzburg, V. L. (May 1959). "Artificial Satellites and the Theory of Relativity". Scientific American. 200 (5): 149–160. Bibcode:1959SciAm.200e.149G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0559-149.

![{\displaystyle {\bar {a}}=-2d_{1}\left({\bar {\omega }}\times {\bar {v}}\right)-d_{2}\left[{\bar {\omega }}\times \left({\bar {\omega }}\times {\bar {r}}\right)+2\left({\bar {\omega }}{\bar {r}}\right){\bar {\omega }}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/746015edea3a36294f39471033272aa670bde435)