Mary Fleming

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Mary Fleming | |

|---|---|

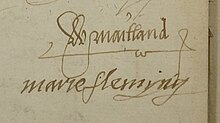

Signature of Mary (bottom) and her husband William Maitland (top) | |

| Born | 1542 |

| Died | Unknown Scotland |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Known for | Lady in waiting to Mary, Queen of Scots |

| Spouse | William Maitland of Lethington |

| Parent(s) | Malcolm Fleming, 3rd Lord Fleming Janet Stewart |

Mary Fleming (/ˈflɛmɪŋ/; also spelled Marie Flemyng; 1542–fl. 1584) was a Scottish noblewoman and childhood companion and cousin of Mary, Queen of Scots. She and three other ladies-in-waiting (Mary Livingston, Mary Beaton and Mary Seton) were collectively known as "The Four Marys".[1] A granddaughter of James IV of Scotland, she married the queen's renowned secretary, Sir William Maitland of Lethington.

Life

[edit]Mary Fleming was the youngest child of Malcolm Fleming, 3rd Lord Fleming, and Lady Janet Stewart. She was born in 1542, the year her father was taken prisoner by the English at the Battle of Solway Moss. Her mother was an illegitimate daughter of James IV of Scotland. Lady Fleming became a governess to the infant queen, also born in 1542, and the dowager queen, Mary of Guise, chose Lady Fleming's daughter Mary to be one of four companions to the young queen. Mary Fleming and Mary, Queen of Scots, were first cousins.

In France

[edit]In 1548, five-year-old Mary Fleming and her mother accompanied Mary, Queen of Scots, to the court of King Henry II of France, where the young queen was raised. Mary Fleming's father having died the previous year in the Battle of Pinkie, her mother had an affair with the French king, the product of which was a son, Henri d'Angoulême, born around 1551.

In 1554, Mary, Queen of Scots played the Delphic Sibyl and Mary Fleming was the Erythraean Sibyl in a masque performed at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, written by Mellin de Saint-Gelais.[2]

Scotland

[edit]Mary, Queen of Scots, and her companions returned to Scotland in 1561 after the death of Francis II of France. The English diplomat Thomas Randolph recorded that the queen was consoled by Mary Fleming when she was disturbed by the discovery of the French poet Chastelard hiding in her bedchamber. After having "some grief of mind", the queen took Mary to be her "bedfellow".[3]

On 26 May 1562 the four women attended Mary at the ceremony of the opening of the Parliament of Scotland. Thomas Randolph described the procession of "four virgins, maydes, Maries, damoyselles of honor, or the Queen's mignions, cawle [call] them as please your honor, but a fayerrer [fairer] syghte was never seen".[4]

During the twelfth day of Christmas pageant in January 1564, Mary Fleming played the part of queen of the Bean.[5] Thomas Randolph was drawn into the dance, and described the costumes:

"The queen of the Bean was that day in a gown of cloth of silver; her head, her neck, her shoulders, the rest of her whole body so be-sett with stones, that more in our whole jewel house were not to be found. The Queen herself that day apparreled in colours white & black, no neither jewel or gold about her that day, but the ring that I brought her from (Queen Elizabeth) hanging at her breast, with a lace of black and white about her neck."[6]

On 19 September 1564, William Kirkcaldy of Grange wrote that the Royal Secretary, William Maitland, was showing an interest in Mary Fleming: "I doubt not but you understand me by now, that our secretary's wife is near dead, and he a suitor to Mrs Fleming, who is as fit for him, as I am to be Pope!"[7]

Marriage to Maitland

[edit]

Mary Fleming married the queen's royal secretary, Sir William Maitland of Lethington, who was many years her senior. The wedding was held at Stirling Castle on 6 January 1567.[8] Jamie Reid-Baxter has suggested that the Scots Renaissance comedy Philotus, about a lecherous octogenarian seeking marriage to a teenage girl, may first have been performed during the Maitland-Fleming wedding celebrations.[9]

The following evidence may suggest that the marriage was successful despite rumors[citation needed] that they were unhappy and that Mary wished to murder her husband:

- The wedding occurred after a three-year courtship that weathered ambivalent relations between Maitland and Mary, Queen of Scots, to whom Mary Fleming was a lady-in-waiting and had been since the age of five.

- Maitland was so infatuated with Mary Fleming that he wrote to William Cecil about it.[citation needed]

- The courtship was the talk of both the Scottish and English courts.

Marian Civil War

[edit]When Mary was imprisoned at Lochleven Castle, Maitland and Mary Fleming sent her a gold jewel depicting the lion and mouse of Aesop's fable. This was a token alluding to the possibility of escape, and his continuing support for her, the mouse could free the lion by nibbling away the knots of the net. Mary wore the jewel at the castle and Marie Courcelles, one of her women provided a description and said it a gift from Fleming.[10] Mary kept this jewel with her in England until her death.[11]

Mary Fleming and her husband were in Edinburgh Castle in 1573 when it was held by supporters of Mary, Queen of Scots against an English army supporting the government of James VI of Scotland. She was captured with her husband when the castle surrendered on 28 May 1573. She was surrendered to Regent Morton and kept a prisoner in Robert Gourlay's House.[12] Her husband was carried out of the castle on a litter because he was unable to stand or walk. He died at Leith on 9 June 1573 before his trial in the custody of William Drury.[13]

Mary Fleming wrote to William Cecil on 21 June imploring that the body of her husband, "which when alive has not been spared in her hieness service, may now after his death, receive no shame or ignominy". As a result, Queen Elizabeth asked Regent Morton to spare the body, which he did.[14]

On 29 June 1573, and again on 15 July, she was ordered to return a chain or necklace of rubies and diamonds in her possession that had belonged to Mary, queen of Scots.[15][16][17] The piece had been a pledge for money lent to William Kirkcaldy of Grange, captain of Edinburgh Castle.[18] The piece was described as "a chayn of rubeis with twelfth merkis of diamantis and rubeis and ane merk with twa rubys in 1578.[19]

Later life

[edit]Mary Fleming did not receive the restoration of Lethington's estate and properties until 1581 or 1582 by grant of King James VI,[20] gaining a rehabilitation on 19 February 1584 for herself and her son. She was allowed the benefit of a property Maitland had given her, Bolton in East Lothian.[21]

She had two children, a boy James, who later became a Catholic and lived in France and Belgium in self-imposed exile, and a daughter Margaret, who married Robert Ker, 1st Earl of Roxburghe. In 1581, Mary, queen of Scots asked Elizabeth I to grant Fleming safe conduct so she could visit the imprisoned queen of Scots. There is no evidence that Mary Fleming went. The last documents attributed to her are her letter to William Cecil and a letter to her sister discussing some bad feelings that existed between Fleming and her brother-in-law Coldingham.

She married secondly, George Meldrum of Fyvie.[22]

In popular culture

[edit]In the 2007 film Elizabeth: The Golden Age, Mary Stuart's lady-in-waiting Annette Fleming, played by Susan Lynch, is an allusion to Mary Fleming.

In the 2013-2017 CW television series Reign, the character Lady Lola Fleming, played by Anna Popplewell, is based on Mary Fleming.

In the 2018 film Mary Queen of Scots, Mary Fleming is played by actress Maria-Victoria Dragus.

Lady Mary Fleming features prominently in the 1820 novel The Abbot by Walter Scott, where she shares Mary Stewart's imprisonment in Lochleven Castle and escape from it.

References

[edit]- ^ French, Morvern. "Mary Fleming and Mary Queen of Scots". Scotland and the Flemish People. St Andrews Institute of Scottish Historical Research. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Alphonse de Ruble, La première jeunesse de Marie Stuart, (Paris, 1891), pp. 95-08.

- ^ Bain, Joseph, ed., Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 886, 688.

- ^ David Hay Fleming, Mary, Queen of Scots (London, 1897), p. 490: HMC Rutland, 1 (London, 1888), pp. 84-5.

- ^ Rosalind K. Marshall, "Prosopographical Analysis of the Female Household", Nadine Akkerman & Birgit Houben, The Politics of Female Households: Ladies-in-waiting across Early Modern Europe (Brill, 2014), p. 224: HMC Pepys Manuscripts at Magdalene College, Cambridge (London, 1911), pp. 11–13

- ^ 'Wigton Papers', Miscellany of the Maitland Club, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1840), pp. 391–2

- ^ Bain, Joseph, ed., Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1900), pp. 34, 75.

- ^ Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queen's Scotland, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1850), p. 87.

- ^ Reid-Baxter, Jamie, "Ane Renaissance Comedy frae the Scottis Court", notes accompanying the Biggar Theatre Workshop production of Philotus, September 1997

- ^ Thomas Duncan, 'The Relations of Mary Stuart with William Maitland of Lethington', The Scottish Historical Review, 5:18 (January 1908), 157: David Hay Fleming, Mary Queen of Scots (London, 1897), 472–473: Joseph Robertson, Inventaires de la Royne Descosse (Edinburgh, 1863), xlix–l.

- ^ Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, 7 (London, 1844), 258.

- ^ Daniel Wilson, Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Time, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1891), p. 226.

- ^ Harry Potter, Edinburgh Under Siege, 1571-1573 (Stroud, 2003), p. 145.

- ^ William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-1574, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), pp. 590–591 no. 700: Harry Potter, Edinburgh Under Siege, 1571-1573 (Stroud, 2003), p. 145.

- ^ John Duncan Mackie, "Queen Mary's Jewels", Scottish Historical Review, 18:70 (January 1921), p. 91

- ^ Charles Thorpe McInnes, Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland: 1566-1574, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1970), p. 355.

- ^ John Hill Burton, Register of the Privy Council, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1878), pp. 246-7.

- ^ Bruce Lenman, 'Jacobean Goldsmith-Jewellers as Credit-Creators: The Cases of James Mossman, James Cockie and George Heriot', Scottish Historical Review, 74:198 part (October 1995), p. 162.

- ^ Thomas Thomson, Collection of Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), pp. 193–194, 262 no. 8.

- ^ Barbé. "The Queen's Marys": 469.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gordon Donaldson, Register of the Privy Seal: 1581-84, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1982), pp. 307, no. 1828, 313 no. 1862.

- ^ Scots Peerage, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1911), p. 541.