Empress Myeongseong

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Needs more references and existing references should be consistently formatted (use Template:Sfn for page numbers). (March 2024) |

| Empress Myeongseong | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empress Consort of Korea (posthumously) | |||||

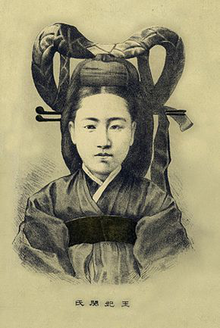

Posthumous drawing of Empress Myeongseong (1898) | |||||

| Queen consort of Joseon | |||||

| Tenure | 20 March 1866 – 1 November 1873 | ||||

| Predecessor | Queen Cheorin | ||||

| Successor | Empress Sunjeong as the Empress of Korea | ||||

| Tenure | 1 July 1894 – 6 July 1895 | ||||

| Predecessor | Herself as the Queen of Joseon | ||||

| Successor | Empress Sunjeong as the Empress of Korea | ||||

| Queen regent of Joseon | |||||

| Tenure | 1 November 1873 – 1 July 1894 | ||||

| Predecessor | |||||

| Successor | None | ||||

| Monarch | Gojong | ||||

| Tenure | 6 July 1895 – 26 September 1895 | ||||

| Predecessor | Regained title | ||||

| Successor | Title and position abolished | ||||

| Monarch | Gojong | ||||

| Born | 17 November 1851 Gamgodang, Seomrak Village, Geundong-myeon, Yeoheung-mok, Kimhwa County, Gyeonggi Province, Kingdom of Joseon[a] | ||||

| Died | 8 October 1895 (aged 43) Okhoru Pavilion, Gonnyeonghap, Gyeongbok Palace, Kingdom of Joseon | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Yeoheung Min (by birth) Jeonju Yi (by marriage) | ||||

| Father | Min Chi-rok, Internal Prince Yeoseong | ||||

| Mother | Internal Princess Consort Hanchang of the Hansan Yi clan | ||||

| Religion | Shamanism | ||||

| Seal |  | ||||

| Korean name | |||||

| Hangul | 명성황후 | ||||

| Hanja | 明成皇后 | ||||

| Revised Romanization | Myeongseong Hwanghu | ||||

| McCune–Reischauer | Myŏngsŏng Hwanghu | ||||

| Birth name | |||||

| Hangul | 민자영 | ||||

| Hanja | 閔玆暎 | ||||

| Revised Romanization | Min Ja-yeong | ||||

| McCune–Reischauer | Min Cha-yŏng | ||||

Empress Myeongseong[b] (Korean: 명성황후; 17 November 1851 – 8 October 1895)[c] was the official wife of Gojong, the 26th king of Joseon and the first emperor of the Korean Empire. During her lifetime, she was known by the name Queen Min (Korean: 민비; Hanja: 閔妃). After the founding of the Korean Empire, she was posthumously given the title of Myeongseong, the Great Empress (명성태황후; 明成太皇后).

The later Empress was of aristocratic background and in 1866 was chosen by the de facto Regent Heungseon Daewongun to marry his son, the future King Gojong. Seven years later his daughter-in-law and her Min clan forced him out of office. Daewongun was a conservative Confucian later implicated in unsuccessful rebellion against his daughter-in-law’s faction. He believed in isolation of Joseon from all foreign contact as a means of preserving independence. She, by contrast, was a believer in gradual modernisation using Western and Chinese help. From 1873 to her assassination in 1895 she oversaw economic, military and governmental modernisation.

In the 1880s and 1890s the relationship between Joseon and neighbouring Japan deteriorated. The queen consort was considered an obstacle by the government of Meiji Japan to its overseas expansion.[1] She took a firmer stand against Japanese influence after Daewongun's failed rebellions that were intended to remove her from the political arena.[2] Miura Gorō, Japanese Minister to Korea, backed the faction headed by Daewongun and directly ordered the assassination. On 8 October 1895, the Hullyeondae Regiment loyal to the Daewongun attacked the Gyeongbokgung Palace and overpowered its Royal Guards. The intruders then allowed a group of ronin, specifically recruited for this purpose, to assassinate the queen consort. Her assassination sparked international outrage.[3]

The Japanese-backed cabinet in the winter of 1895–1896 ordered Korean men to cut off their top-knot of hair. This caused uproar, because this style of hair was considered a badge of Korean identity.[4] This topknot edict and the assassination provoked nationwide protests.[5][6] Gojong and the Crown Prince (later Emperor Sunjong of Korea) accepted refuge in the Russian legation in 1896. The anti-Japanese backlash led to the repeal of the Gabo Reform, which had introduced other measures increasing Japanese influence.[5] In October 1897, Gojong returned to Gyeongungung (modern-day Deoksugung). Whilst there, he proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire[5] and raised the status of his deceased wife to Empress.

Names and titles

[edit]As was the custom in late Joseon society, the woman who came to be Empress Myeongseong never had a personal name. "Min" is the name of her clan. "Empress" was a title conferred after her assassination. Changes in her marital status or the status of her husband are reflected in her own title. In Western terms, she was nameless throughout her life.[7] For the most part, the narrative below refers to her as the queen consort because that was her title during life at the beginning of her political activity, and was her functioning position. For convenience the description queen regent is not separately used.

Background

[edit]Clan tensions at the death of the King

[edit]In 1864, at the age of 32, Cheoljong of Joseon died suddenly[8][9] under ambiguous causes. Cheoljong was childless and had not appointed an heir.[8] The Andong Kim clan had risen to power through intermarriage with the royal House of Yi. Queen Cheorin, Cheoljong's consort and a member of the Andong Kim clan, claimed the right to choose the next king. Traditionally, the most senior Queen Dowager had the official authority to select the new king. Cheoljong's cousin, Grand Royal Dowager Hyoyu (once known as Queen Sinjeong), was the most senior Dowager. She was of the Pungyang Jo clan and the widow of Heonjong of Joseon's father. She had risen to prominence by intermarriage with the Yi family.

Alliance between the Pungyang Jo clan and Yi Ha-eung

[edit]Grand Queen Dowager Hyoyu saw an opportunity to advance the cause of her Pungyang Jo clan, the only true rival of the Andong Kim clan in Korean politics. As King Cheoljong was dying, she was approached by Yi Ha-eung, a distant descendant of King Injo (r.1623–1649), whose father was made an adoptive son of Prince Eunsin, a nephew of King Yeongjo (r.1724–1776).

The branch that Yi Ha-eung's family belonged to was a distant line of descendants of the Yi clan. They survived the often deadly political intrigue that frequently embroiled the Joseon court by forming no affiliation with any factions. Yi Ha-eung himself was not eligible for the throne due to a law that dictated that a successor had to be part of the generation after the most recent monarch. Yi Ha-eung's second son, Yi Myeong-bok, was a possible candidate for the throne.

The Pungyang Jo clan saw that Yi Myeong-bok, was only 12 years old and would not be able to rule in his own name until he came of age. They hoped to influence Yi Ha-eung, who would be acting as de facto regent for his son. (Technically Grand Queen Dowager Hyoyu would be regent but in fact she did not intend to play an active role in the regency). As soon as news of King Cheoljong's death reached Yi Ha-eung through his intricate network of spies in the palace, the hereditary royal seal required for the selection of a new monarch was taken to or by Grand Queen Dowager Hyoyu. She already was strictly entitled to make the appointment.[10] She thereupon chose her great-grandson, Yi Myeong-bok. The Andong Kim clan was powerless to act because the formalities had been observed.

Accession of a new King

[edit]In the autumn of 1864, Yi Myeong-bok was renamed as Yi Hui (이희, 李㷩) and was crowned as Gojong King of Joseon, with his father as Regent titled as Grand Internal Prince Heungseon. He is referred to in this article henceforth as Heungseon Daewongun or Daewongun.

The strongly Confucian Daewongun proved to be a decisive leader in the early years of Gojong's reign. He abolished the old government institutions that had become corrupt under the rule of various clans, revised the law codes along with the household laws of the royal court and the rules of court ritual, and heavily reformed the military techniques of the royal armies. Within a few years, he was able to secure complete control of the court, and eventually receive the submission of the Pungyang Jos while successfully disposing of the last of the Andong Kims, whose corruption, he believed, was responsible for the country's decline in the 19th century.

Early life and family

[edit]

Yeoheung Min clan antecedants

[edit]The future queen consort was born into the aristocratic Yeoheung Min clan on 17 November 1851[11][12][13][14] within the House of Gamgodang in Seomrak Village, Geundong-myeon, Yeoheung (present-day Yeoju), Gyeonggi Province, where the clan originated.[15]

The Yeoheung Mins were a noble clan boasting many high-ranking bureaucrats in its illustrious past, princess consorts, and two queen consorts. These were firstly, Queen Wongyeong (wife of Taejong of Joseon and mother of Sejong the Great) and, secondly, Queen Inhyeon (second wife of Sukjong of Joseon).[15]

When her father Min Chi-rok was young, he studied under scholar Oh Hui-sang (오희상; 吳熙常), and eventually married the scholar's daughter. She became Min Chi-rok's first wife, Lady Oh of the Haeju Oh clan. In 1833 Lady Oh died childless at the age of 36. After three years' mourning, Min Chi-rok in 1836 married Lady Yi of the Hansan Yi clan (later known as Internal Princess Consort Hanchang). She was the daughter of Yi Gyu-nyeon. The future Empress was the fourth and only surviving child of Lady Yi.

Before her marriage, the later empress was known as the daughter of Min Chi-rok, Lady Min, or Min Ja-yeong (민자영; 閔玆暎).[16] At age seven, she lost her father to an illness on 17 September 1858[d] while he was in Sado city. Lady Min was raised by her mother and Min relatives for eight years until she moved to the palace and became queen.[17] Lady Min assisted her mother for three years while in living in Gamgodang. In 1861 it was decided that Min Seung-ho, would become her father's heir.

Selection as queen consort and marriage

[edit]When Gojong reached the age of 15, his father began to seek a bride for his son. Ideally the choice would be a person without politically ambitious relatives and someone who was of noble lineage. After rejecting numerous candidates, the Daewongun's wife, Grand Internal Princess Consort Sunmok (known at the time as Grand Internal Princess Consort Yeoheung; Yeoheung Budaebuin; 여흥부대부인; 驪興府大夫人)[e] and his mother, Princess Consort Min, proposed a bride from their own clan, the Yeoheung Min.[15] The girl's father was dead. She was said to possess beautiful features, a healthy body, and an ordinary level of education.[15]

This possible bride underwent a strict selection process, culminating in a meeting with the Daewongun on 6 March, and a marriage ceremony on 20 March 1866.[18] The Daewongun, likely fearing that the Andong Kim clan and the Pyungyang Jo clan, who were political rivalries for the future, may have been influenced favourably towards Lady Min due to her lack of a father or brother. He did not suspect Lady Min herself as politically ambitious, and he was satisfied with the interview.[19] It was only later he observed that she "...was a woman of great determination and poise“ but that he nevertheless allowed her to marry his son.[20] In doing so, he raised to the throne a woman who by 1895 had proven herself to be "his chief foil and implacable enemy."[21]

Lady Min, aged 16, married the 15-year-old king and was invested in a ceremony (책비, chaekbi) as the Queen Consort of Joseon.[f] Two places assert claims as the location of the marriage and accession. These are Injeongjeon Hall (인정전) at Changdeok Palace[15] and Norakdang Hall (노락당) at Unhyeon Palace. The headdress typically worn by brides at royal weddings was so heavy for the bride that a tall court lady was specially assigned to support it from the back. Directly following the wedding was the three-day ceremony for reverencing of ancestors.[22]

When Lady Min became Queen Consort, her mother was given the royal title of "Internal Princess Consort Hanchang" (한창부부인; 韓昌府夫人). Her father was given the royal title of "Internal Prince Yeoseong" (여성부원군; 驪城府院君), and was posthumously appointed as Yeonguijeong after his death.[23][24][25] Her father's first wife also given the royal title of "Internal Princess Consort Haeryeong" (해령부부인; 海寧府夫人).

On the day of their marriage ceremony, Gojong did not go to his wife's quarters to consummate the marriage, but to the quarters of concubine Royal Consort Yi Gwi-in of the Gyeongju Yi clan. This preference would later be approved by the Heungseon Daewongun.[26][27]

The first impression of the queen consort at the palace was that she was dutiful and docile. Over time, Daewongun changed his view of her.[19] Officials noticed that the new queen consort differed from previous queens before her in her choices and determination. She did not participate in lavish parties, rarely commissioned extravagant fashions from the royal ateliers, and almost never hosted afternoon tea parties with the various princesses of the royal family or powerful aristocratic ladies unless politics required her to do so. Expected to act as an icon for Korea's high society, the queen rejected this role. Instead, she spent her time reading books written using Chinese characters, whose use in Korea was usually reserved for aristocratic men. Spring and Autumn Annals and its accompanying Zuo Zhuan[15] are examples. She furthered her own education in history, science, politics, philosophy, and religion.

As queen consort

[edit]Court domination

[edit]By the age of twenty, the queen consort had begun to leave the total seclusion of her apartments at Changgyeong Palace and to play an active part in politics. This was not at the invitation of Heungseon Daewongun and his high officials. Daewongun directed his son to conceive through the concubine Yi Gwi-in from the Yeongbo Hall (영보당귀인 이씨).[g] On 16 April 1868, the concubine gave birth to Prince Wanhwa (완화군), to whom Daewongun gave the title of crown prince. It was said that Daewongun was overwhelmed with joy at the arrival of Gojong's first born son, and that afterwards the queen consort was not accorded respect or honour as before.[19]

Discord between the queen consort and Daewongun became public when her infant son died in late 1871 four days after birth. Daewongun publicly accused her of being unable to bear a healthy male child. She suspected her father-in-law of foul play through the ginseng emetic treatment he had brought her.[28] It seems likely the queen consort's intense distrust of her father-in-law dates from this time.

Meanwhile the queen consort secretly formed a powerful faction against the Heungseon Daewongun. With the backing of high officials, scholars, and members of her clan, she desired to remove Daewongun from power. Min Seung-ho, the queen consort's adoptive older brother, along with court scholar Choe Ik-hyeon, devised a formal impeachment of Daewongun. The impeachment was to be presented to the Royal Council of Administration, arguing that the 22 year old Gojong should now rule in his own right. In 1873, with the approval of Gojong and the Royal Council, the Heungseon Daewongun was forced to retire to Unhyeongung, his estate at Yangju. The queen consort then banished the royal concubine along with her child to a village outside the capital.[29] The child was stripped of royal titles and died on 12 January 1880.

After these expulsions, the queen consort had control over the court, where her own clan family members received high office. As queen consort she ruled along with her husband but was recognized as being more politically active than him.[30]

Start of imperial Japanese influence

[edit]After Korean refusal to receive Japanese envoys announcing the Meiji Restoration, some Japanese aristocrats favored an immediate invasion of Korea. Upon the return of the Iwakura Mission, this idea was quickly dropped because the new Japanese government was neither politically nor fiscally stable enough to start a war.[31] When Heungseon Daewongun was ousted from politics, Japan renewed efforts to establish ties with Korea, but the Imperial envoy arriving at Dongnae in 1873 was turned away.[32]

In 1875 the Japanese gunboat Unyō was dispatched towards Busan and a second warship was sent to the Bay of Yeongheung, ostensibly surveying sea routes. On 20 September 1875 in a move seen by the Koreans as provocative, the Unyō,ventured into restricted waters off Ganghwa Island. Korean shore batteries then opened fire. Thus arose a violent confrontation between the Japanese and the Koreans known as the Ganghwa Island incident.[33] Following this incident, six naval vessels and an imperial Japanese envoy were sent to Ganghwa Island to enforce the wishes of the Japanese government, which was then in a position to insist on Korea opening to trade generally. There was precedent for this line of action in the behaviour of European powers and their extraction of the so-called Unequal Treaties.

Whilst a majority of the royal Korean court favored absolute isolationism, Japan had demonstrated its willingness and capacity to use force. The deposed Daewongun took the opportunity to blame the Min clan for their weakness in contrast to his own previous isolationist, anti-foreign policies.[34] After numerous meetings, the Ganghwa Treaty was signed on 26 February 1876, thus opening Korea to Japan and the world. The treaty was modeled after treaties imposed on Japan by the United States. Various ports were forced to open to Japanese trade, and Japanese now had rights to buy land in designated areas. The treaty permitted the immediate opening of Busan (1876) and later other major ports, Wonsan (1880) and Incheon (1883) to Japanese merchants. For the first few years, Japan enjoyed a near total monopoly of trade. Japanese cotton goods were imported to Korea, which was unindustrialised and still dominantly dependent on limited modes of agricultural production. Rice and cereals became the main export to Japan, whose merchants came to inhabit the major ports.[35] By 1894 Busan gave every appearance, according to doctor-missionary Isabella Bird, of being a town in Japan. She reports the fact that the customs were levied by the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs officers on behalf of the Korean Crown. At least one of these officers was English.[36]

Social revolution

[edit]Reorganisation of Joseon government

[edit]In 1880, a mission headed by Kim Gi-su (Kim Hong-Jip) was commissioned by Gojong and the Min clan to study Japanese westernisation and its intentions for Korea. The immediate diplomatic objective was to persuade the Japanese that there was no need to open a Legation in Seoul and that the port of Incheon should not be opened.[37] It arrived on 11 August 1880.

While in Japan, Kim visited the Chinese embassy in Japan no less than six times. He met with the Chinese first envoy to Japan, He Ru-zhang,[38] and his staff adviser, Huang Zunxian. In September 1880, a prepared paper was written for the benefit of, and was presented to, the visiting Koreans, the purpose of which was to change their whole approach towards modernisation through external contact. This paper, whose text survives in five differing forms, was written by Huang. It was entitled Korean Strategy and examined the strategic position of Korea in the context of its need for strength in the international situation of the day. The essence of its thesis was that Russia was land-hungry and represented the primary threat to Korea. The Chinese, it argued, should be regarded as natural close allies from whom full independence was undesirable. Huang advised that Korea should adopt a pro-Chinese policy, while retaining close ties with Japan for the time being. He also advised an alliance with the United States in particular because it did not occupy the countries with which it traded, and because it would be a protection against Russia. He considered it wise to open trade relations with Western nations and to adopt Western technology, arguing that their interest in Korea was trade rather than occupation. The modernisation of Japan through Western contact was pointed to as a promising precedent for study.

Kim returned from Japan in late 1880. By early 1881 the paper had made a considerable impression on the king and the queen consort.[39] Copies were commissioned to be sent out to all ministers. She had hoped to win yangban (aristocratic) approval to invite Western nations into Korea, and to open up trade so as to keep Japan in check. She wanted to first allow Japan to help in the modernisation process but after completion of certain projects, have them be driven out by Western powers. However, the yangban aristocracy opposed any opening of the country to the West. Choi Ik-hyun, who had helped with the impeachment of Heungseon Daewongun, sided with the isolationists. He maintained that the Japanese were just like the "Western barbarians" and would spread subversive notions, just as previous Western contact had brought Roman Catholicism. That had been a major issue during Daewongun's regency and Catholicism was crushed by widespread persecution.[40]

To the socially conservative yangban, the queen consort's plan meant the end of social order. Accordingly, the response to the distribution of Korean Strategy was a joint memorandum to the throne from scholars in every province of the kingdom. They stated that the ideas in the book were impractical theories, and that the adoption of Western technology was not the only way to enrich the country. They demanded that the number of envoys exchanged, ships engaged in trade and articles of trade be strictly limited, and further that all foreign books in Korea should be destroyed. Two thousand (out of office) scholars gathered at Cho-rio, planning to march on Seoul and overwhelm the serving Ministers. The gathering was met at Cho-rio by royal envoys who promised to stop the mission to Japan, to which the protesters objected. It was too late, however, and the Korean mission by then had landed in Nagasaki in Japan.[41]

Thus in 1881, a large fact-finding mission was sent to Japan under Kim Hongjip. It stayed for seventy days observing Japanese government offices, factories, military and police organizations, and business practices. The visitors obtained information about innovations in the Japanese government copied from the West, especially the proposed constitution. On the basis of these reports, the queen consort began reorganisation of the government.[42] Twelve new bureaus were established to deal with foreign relations with the West, China, and Japan. Other bureaus were established to supervise commerce. A bureau of the military was created, tasked to modernize weapons and techniques. Civilian departments were established to import Western technology.

Meanwhile in September 1881, a plot was uncovered to overthrow the queen consort's faction, depose the King, and place Heungseon Daewongun's illegitimate (third) son, Yi Jae-seon (known posthumously as Prince Imperial Waneun) on the throne. The plot was frustrated by informants to[43] and spies of the queen consort. Heungseon Daewongun (whose involvement was not proved) was unharmed. However, the attempted coup resulted in Yi Jae-seon's death in late October 1881.

In October 1881, the queen consort arranged for 60 top Korean military students to be sent to Tientsin in Qing China where they were to study arms manufacturing and deployment.[44] The Japanese volunteered to supply military students with rifles and train a unit of the Korean army to use them. She agreed but reminded the Japanese that students would still be sent to China for further education on Western military technologies. The modernisation of the military was met with opposition.

The insurrection of 1882

[edit]In June 1882, members of the old military became resentful of the special treatment of the new units. They destroyed the house of Min Gyeom-ho and killed him. He was Gojong's maternal uncle, being his mother's younger brother, and was the administrative head of the training units and in charge of the treasury. Yi Choi-eung and Kim Bo-hyun, a magistrate, were also killed.[45] These had been associated with the Min corruption whereby the soldiers got rotten rice in payment of wages. These soldiers then fled to the protection of Daewongun, who publicly rebuked but privately encouraged them. Daewongun took control of the old units. He ordered an attack on the administrative district of Seoul that housed the Gyeongbokgung, the diplomatic quarter, military centers, and science institutions. These soldiers attacked police stations to free comrades who had been arrested and ransacked private estates and mansions belonging to relatives of the queen consort. These units stole rifles and killed Japanese training officers. They narrowly missed murdering the Japanese ambassador to Seoul, who escaped to Incheon, and thence to Japan where he was interviewed at court for an account of events.[46] The military rebellion then headed towards the palace but both queen consort and the King escaped in disguise. They fled to her relative's villa in Cheongju, where they remained in hiding.[h] Rumour supplied differing accounts of the escape. The truth may lie in the detailed account recorded by Homer Hulbert.[47]

One rumour was that Grand Internal Princess Consort Sunmok had entered the palace, and hidden her daughter-in-law, the queen consort, in a wooden litter that the older woman was riding on. Allegedly a court officer saw this and informed the soldiers invading the palace.[48]

Princess Sunmok did try to persuade her husband Heungseon Daewongun to stop the hunt for the queen consort. This seemed so suspicious that later he kept her away from his affairs.[49] When Daewongun could not find the queen consort, he likely assumed she was dead (according to Hulbert). He announced, "the queen is dead".[50][51][52] Numerous supporters of the queen consort were executed once Daewongun took control of Gyeongbokgung Palace. He immediately dismantled the recent reform measures and relieved the new units of duty. Foreign policy reverted to isolationism. Both Chinese and Japanese representatives were forced to leave the capital.

Li Hongzhang, with the consent of Korean envoys in Beijing, sent 4,500 Chinese troops to restore order and secure Chinese interests in Korea. His troops arrested Daewongun, who was then taken to Paoting in China where he remained under house arrest.[53] The royal couple returned and overturned all of Daewongun's actions.

The Japan-Korea Treaty of 1882, signed on 10 August 1882 required the Koreans to pay 550,000 yen damages in respect of Japanese lives and property lost during the insurrection. This agreement also permitted Japanese troops to guard the Japanese embassy in Seoul. The queen consort proposed to China a new trade agreement granting the Chinese special privileges and rights to ports inaccessible to the Japanese. Public order was enforced by Wu Chang-ching and his detachment of 3,000 Chinese troops. She also successfully requested that a Chinese commander, General Yuan Shih-kai, take control of the new military units and that a German adviser, Paul Georg von Möllendorff, head the Maritime Customs Service. The Chinese desired further trade treaties so as to deflect a Japanese monopoly. Treaties were later signed with the United States (1882) and France (1886).[45]

Mission to North America

[edit]In July 1883 the queen consort sent a special mission to the United States. It was headed by Min Yeong-ik, her adoptive nephew. The mission arrived at San Francisco on 2 September 1883 carrying the newly created Korean national flag. It visited U.S. historical sites, heard lectures on U.S. history, and attended a gala event in their honor given by the mayor of San Francisco and other U.S. officials. The mission dined in New York at the Fifth Avenue Hotel with President Chester A. Arthur, and discussed the growing threat of the Japanese and the possibility of U.S. investment in Korea. The Korean visit lasted three months, returning via San Francisco.[54] At the end of September, Min Yeong-ik travelled to Seoul and reported to the queen consort. She at once established English language schools with U.S. instructors. Min Yeong-ik's report had been optimistic:

I was born in the dark. I went out into the light, and, your Majesty, it is my displeasure to inform you that I have returned to the dark. I envision a Seoul of towering buildings filled with Western establishments that will place herself back above the Japanese barbarians. Great things lie ahead for this Kingdom, great things. We must take action, your Majesty, without hesitation, to further modernize this still ancient kingdom.

Matters culminated in October 1883 with a royal request that the Americans send an adviser to Korea to the office of foreign affairs, and instructors for the army. An order for arms was placed with a US firm based in Yokohama.[55] A complement of three military instructors arrived in April 1888.[56]

Progressives vs Conservatives

[edit]The Progressives were founded during the late 1870s by a group of yangban who supported westernisation of Joseon. They wanted immediate westernisation, including a complete cessation of ties with Qing China. With the queen consort possibly unaware of their anti-Chinese sentiments, they were granted frequent royal audiences and meetings to discuss progressivism and nationalism. They advocated for educational and social reforms, including the equality of the sexes by granting women full rights. The queen consort was convinced at first, but she did not support their anti-Chinese stance. In the result, she became a proponent of the Sadae faction which was pro-China and in favour of gradual westernisation.

In 1884, the conflict between the Progressives and the Sadaes intensified. The Progressives, frustrated by the Sadaes and the growing influence of the Chinese, successfully conspired to secure the aid of Japanese Legation staff and troops.[57] American Legation officials, in particular Naval Attaché George C. Foulk, heard about the possibility of trouble breaking out caused by the Progressives. This rumour reached the British who put out feelers to their various other contacts. All this found its way back to the chief Progressive conspirators, who, fearing their dangerous game was almost up, decided to act immediately.[58]

They staged a bloody palace coup on 4 December 1884 (the Gapsin Coup) on the occasion of a diplomatic dinner celebrating the opening of the new Korean postal service.[59] The Progressives killed numerous high-ranking Sadaes and secured key government positions vacated by Sadaes who had fled the capital or had been killed. This new administration began to issue edicts in both the King and queen consort's names. The King and the queen consort had been kidnapped and were held prisoner by armed Japanese guards. The new cabinet did not secure popular support despite their agenda of modernisation and planned political, economic, social, and cultural reforms.[60]

The queen consort was horrified by the violence of the Progressives. They effected seven murders of high-ranking Koreans. Clan leaders summoned to the palace by letters purporting to come from the King were beheaded on stepping out of their sedan chairs.[61] Following suppression of the coup, the queen consort no longer trusted the Japanese.[62] She refused to support the actions of the Progressives, declaring any documents signed in her name to be null and void. After only two days[63] of control over the administration, the Progressives were crushed by Chinese troops under Yuan Shikai's command. These were sent following a secret request by the queen consort to the Chinese Resident. A handful of Progressive leaders were killed, others escaping to Japan.[64] The Japanese troops were only 130 in all and were easily overwhelmed. Japanese deaths and property damage followed. The Treaty of Hanseong (8 January 1885) negotiated by Count Inouye on behalf of the Japanese required Joseon to pay a "moderate" indemnity for damages inflicted: 40 Japanese were killed during the coup and the Japanese legation was burned to the ground. In addition, the Koreans agreed to rebuild the Japanese Legation plus some barracks for their troops. Lastly, those guilty of murdering a Japanese officer were to be punished.[65]

On 18 April, the Convention of Tientsin (1885) was made in Tianjin, China, between the Japanese and the Chinese. In it, they both agreed to pull troops out of Joseon. Each party agreed it would send troops only if their property was endangered; each would inform the other before doing so. Both nations also agreed to pull out their military instructors so as to allow the newly arrived Americans to perform that task. The Japanese withdrew troops from Korea, leaving a number of legation guards.

Public policy

[edit]Economy

[edit]

Following the opening of all Korean ports to the Japanese and Western merchants in 1888, contact and involvement with outsiders increased foreign trade rapidly. In 1883, the Maritime Customs Service was established under the patronage of the queen consort and the supervision of Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet of the United Kingdom. The Maritime Customs Service administered the business of foreign trade and collection of tariffs.

By 1883, the economy was now no longer in a state of monopoly conducted by Japanese merchants as it had been only a few years ago. Much of the economy was controlled by the Koreans, with some participation shared between Western nations, Japan and China. In 1884, the first Korean commercial firms such as the Daedong and the Changdong Company emerged. The Korean copper coinage had been debased to the exchange of 500 cash to one US dollar. This meant that transactions in cash were heavy and bulky. It was not a currency suited to the scale of commercial transactions. Japanese yen and Japanese banks were used everywhere.[66] In 1883 the Korean Bureau of Mint produced a new coin, tangojeon or dangojeon thereby securing a stable Korean currency, but in the five years following the new currency was blamed, rightly or wrongly, for the inflation of basic commodities.[67] Western investment also began to grow in 1886. One third of all imported goods were carried inland by men or pack animals. They were frequently stopped and taxed for transit by road barriers on the way. The Seoul government in exchange for a fee authorised these barrier levies.[68]

The German A.H. Maeterns, with the aid of the United States Department of Agriculture, created a new project designated the "American Farm."[69] This was on a large plot of land donated by the queen consort to promote modern agriculture. Farm implements, seeds, and milk cows were imported from the United States. In June 1883, the Bureau of Machines was established and steam engines were imported. Finally, telegraph lines facilitating communication between Joseon, China, and Japan were laid between 1883 and 1885.[69]

Despite the fact that the royal couple had brought the Korean economy to a degree of westernisation, modern manufacturing facilities did not emerge.

Education

[edit]From early projections in 1880, in May 1885 a palace school to educate the children of the elite was approved by the queen consort. The Royal English School (육영공원; 育英公院; Yukyŏng Gongwŏn) was established by the American missionary Homer Hulbert and three other missionaries. The school had two departments, liberal education and military education. Courses were taught exclusively in English using English textbooks. However, due to low attendance, the school was closed shortly after the last English teacher, Bunker, resigned in late 1893.[70]

In 1886, the queen consort patronized the first all-girls' educational institution, Ewha Academy (later Ewha University). The school was established in Seoul by Mary F. Scranton. She collaborated with Methodist missionary and teacher Henry Gerhardt Appenzeller, who worked in Korea from 1885 to his death in June 1902.[71] As Louisa Rothweiler, a founding teacher of Ewha Academy observed, the school was, at its early stage, more of a place for poor girls to be fed and clothed than a place of education.[70] The creation of the academy was a significant social change.[72]

Missionaries contributed much to the development of Western education in Joseon.

Medicine, music, and religion

[edit]The arrival of Horace Newton Allen under invitation of the queen consort in September 1884 marked the formal introduction of Christianity, which spread rapidly in Joseon. He was able, with the queen consort's permission and official sanction, to arrange for the appointment of other missionaries as government employees. He also introduced modern medicine in Korea by establishing the first western Royal Medical Clinic of Gwanghyewon in February 1885.[i]

In April 1885, numerous Protestant missionaries began to arrive in Joseon. Prominent Protestant missionaries Horace Grant Underwood, Lillias Horton Underwood, and William B. Scranton (with his mother, Mary Scranton) moved to Korea in May 1885. They established churches within Seoul and began to establish centers in the countryside. Catholic missionaries arrived soon afterwards.

Christian missionaries made converts but also created contributions towards modernisation of the country. Concepts of equality, human rights and freedom, and the participation of both men and women in religious activities were introduced for the first time to Joseon. The queen consort wanted the literacy rate to rise, and with the aid of Christian educational programs, it did so within a matter of a few years.

Notable changes were made in music. Western music theory partly displaced the traditional Eastern concepts. Protestant missions introduced Christian hymns and other Western songs that created a strong impetus to modify Korean ideas about music. The organ and other Western musical instruments were introduced in 1890, and a Christian hymnal was published in the Korean language in 1893 under the commission of the queen consort.

The queen consort invited different missionaries to enter Joseon. She valued their knowledge of Western history, science, and mathematics. It can be assumed these advantages were seen as outweighing the potential loss of ancestor worship, which Catholic converts were well-known to have resisted in face of sustained persecution in the past.[73] Isolationists continued to view Christianity as subversive of morals in the refusal to perform rites for ancestors and the perceived disloyalty to the state. Some scholars had attempted to classify Christianity not as a religion but a school of learning.[74] A degree of religious tolerance was a practical outcome of the queen consort's policies, whether or not it had been an overt goal. The queen consort herself never became a Christian, but remained a devout Buddhist with influences from shamanism and Confucianism.

Military

[edit]Modern weapons were imported from Japan and the United States in 1883. The first military factories were established and new military uniforms were created in 1884. In a show of her support for pro-American government, a request was made to the United States for more American military instructors to speed up the military modernisation of Korea under joint patronage of Gojong and the queen consort. Military modernisation was slow compared to the other projects.

In October 1883, American minister Lucius Foote arrived to take command of the modernisation of Joseon's older army units, which had not started to Westernise. In April 1888, General William McEntyre Dye and two other military instructors arrived from the United States, followed in May by a fourth instructor. They brought about more rapid military development.[75]

A new military school was created called Yeonmu Gongwon, and an officers' training program began. Visible progress in the preparedness and capacity of the Korean military was being achieved. The growing troop numbers caused the Japanese concern as to the possible impact of Korean troops if the Japanese government did not interfere to stall the process. By 1898 the Korean army comprised 4,800 men in Seoul who were drilled by the Russians at that time. There were 1,200 Korean soldiers in the provinces and the navy owned two small vessels.[76]

Despite army training becoming increasingly on par with that of the Chinese and the Japanese, naval investment of all kinds was neglected. This omission represented a gap in the modernisation project. Failure to develop naval defence rendered Joseon's long sea borders more vulnerable to invasion. This was a severe contrast to the period nearly 300 years earlier when Joseon's navy under Admiral Yi Sun-sin had been the strongest in East Asia.[77] Now, the Korean navy comprised old ships almost powerless against the advanced ships of modern navies.

Press

[edit]

The first newspaper to be published in Joseon was the Hanseong Sunbo Hanseong Sunbo, an all-Hanja newspaper. It was published as a thrice monthly official government gazette by the Bakmun-guk (publishing house), an agency of the Foreign Ministry. It included contemporary news of the day, essays and articles about westernisation, and news of modernisation of Joseon. In January 1886, the Bakmun-guk published a new newspaper, Hanseong Jubo (The Seoul Weekly). The publication of a Korean-language newspaper was a significant development, and the paper itself played an important role as a communication medium to the masses until it was abolished in 1888 under pressure from the Chinese government. A newspaper entirely in Hangul, making no use of the Korean Hanja script, was not published again until 1894. Kanjō Shinpō was published as a weekly newspaper under the patronage of both Gojong and the queen consort. It was written half in Korean and half in Japanese.

Reforms, rebellion, and war

[edit]Trade 1875 onwards

[edit]

The queen consort's economic reforms opened the Korean economy to the world, but in practice the majority of trade for Korean agricultural products was with China and Japan. After the failure of the Progressive coup, Japanese policy focused on expanding economic ties. Between 1877-81 imports into Korea increased by 800%; between 1885-1891 rice and other grain exports increased by 700%. Most grain was exported to Japan via Osaka. Many kinds of household and luxury goods were imported into Korea, in turn encouraging officials to demand extra or new taxes from the farmers.[78] Between 1891 and 1895 the chief Korean exports were rice, beans, tobacco, raw hides, gold dust and silk. Ginseng was now permitted to be exported as a privately traded product, the old government monopoly ending and being replaced by high taxation. The 1895 trade value was almost 13 million US dollars of the day.[21]

Economic activity between 1883 and 1897 was conducted in a society unprepared for the impact of mass importation of foreign-produced goods, largely from Japan.[79] In the period 1886 to 1888 an ineffective currency reform fuelled inflation; it was not until 1897 that relative price stability in textiles was experienced.

From 1875 to 1894, Korea signed 11 treaties with 9 foreign powers. These were: Austria (1892); China (1882); France (1886); Germany (1883); Great Britain (1883); Italy (1884); Japan (1876), (1882), (1885); Russia (1884); and the United States of America (1882). Their descriptions and chronological sequence are given with Korean names elsewhere.[80]

Political instability 1894–1895

[edit]

Under this external economic pressure, Korean peasants decided to protest, then rebel. The Donghak Peasant Revolution, that lasted from January 1894 to 25 December 1895, presented the queen consort with an extremely dangerous situation. Its causes are complex, being religious, nationalistic and economic. The queen consort was assassinated in October 1895 before this matter was resolved. During 1894, much of Southern Korea was in a state of open peasant revolt which the government could not control. The Chinese were requested by Korea to send troops to restore order, which they did, hoping to establish a fully committed pro-Chinese policy at court. The Japanese government unilaterally sent troops to Korea, abducting the now pro-Chinese Daewongun and effecting a violent coup at the palace resulting in a pro-reform, pro-Japanese government. By this time the peasants had largely withdrawn and neither Japanese nor Chinese troops were required for any Korean purpose. Each side refused to return troops to their country of origin until the other did so first.[81] Thus arose the First Sino-Japanese War (January 1894-25 December 1895) in which the Japanese were the decisive victors.

Personal life

[edit]Personality and appearance

[edit]Detailed descriptions of the queen consort can be found in The National Assembly Library of Korea and in records kept by Lillias Underwood[82] a close and trusted American friend of the queen consort. Underwood had come to Korea in 1888 as a missionary and was appointed by the queen consort as her doctor.

These sources describe the queen consort's appearance, voice, and public manner. She was said to have had a soft face with strong features. These were considered attributes of classic beauty in contrast to the king's known preference for "sultry" women. The queen consort's personal speaking voice was soft and warm, but when conducting affairs of the state, she asserted her points with strength. Her public manner was formal, and she heavily adhered to court etiquette and traditional law. Underwood described her in the following way:[83]

I wish I could give the public a true picture of the queen as she appeared at her best, but this would be impossible, even had she permitted a photograph to be taken, for her charming play of expression while in conversation, the character and intellect which were then revealed, were only half seen when the face was in repose. She wore her hair like all Korean ladies, parted in the center, drawn tightly and very smoothly away from the face and knotted rather low at the back of the head. A small ornament...was worn on the top of the head fastened by a narrow black band...

Her majesty seemed to care little for ornaments, and wore very few. No Korean women wear earrings, and the queen was no exception, nor have I ever seen her wear a necklace, a brooch, or a bracelet. She must have had many rings, but I never saw her wear more than one or two of European manufacture...

According to Korean custom, she carried a number of filigree gold ornaments decorated with long silk tassels fastened at her side. So simple, so perfectly refined were all her tastes in dress, it is difficult to think of her as belonging to a nation called half civilized...

Slightly pale and quite thin, with somewhat sharp features and brilliant piercing eyes, she did not strike me at first sight as being beautiful, but no one could help reading force, intellect and strength of character in that face...

Isabella Bird Bishop, a well-known British travel writer and member of the Royal Geographical Society, described the queen consort's appearance as that of "...a very nice-looking slender woman, with glossy raven-black hair and a very pale skin, the pallor enhanced by the use of pearl powder" while meeting with her when Bishop traveled to Korea.[84] Bishop had also mentioned Empress Myeongseong in her book, Korea and Her Neighbors:

Her Majesty, who was then past forty, was a very nice-looking slender woman, with glossy raven-black hair and a very pale skin, the pallor enhanced by the use of pearl powder. The eyes were cold and keen, and the general expression one of brilliant expression. She wore a very handsome, very full, and very long skirt of mazarine blue brocade, heavily pleated, with the waist under the arms, and a full sleeved bodice of crimson and blue brocade, clasped at the throat by a coral rosette, and girdled by six crimson and blue cords, each one clasped with a coral rosette, with a crimson silk tassel hanging from it. Her headdress was a crownless black silk cap edged with fur, pointed over the brow, with a coral rose and full red tassel in front, and jewelled aigrettes on either side. Her shoes were of the same brocade of her dress. As soon as she began to speak, and especially when she became interested in conversation, her face lighted up into something very like beauty.

— Isabella L. Bird, Korea and Her Neighbors, pp. 252–253

On each occasion I was impressed with the grace and charming manner of the Queen, her thoughtful kindness, her singular intelligence and force, and her remarkable conversational power even through the medium of an interpreter. I was not surprised at her singular political influence, or her sway over the King and many others. She was surrounded by enemies, chief among them being Tai-Won-Gun (Daewongun), the King's father, all embittered against her because by her talent and force she had succeeded in placing members of her family in nearly all the chief offices of State. Her life was a battle. She fought with all her charm, shrewdness, and sagacity for power, for the dignity and safety of her husband and son, and for the downfall of Tai-Won-Gun.

— Isabella L. Bird, Korea and Her Neighbors, p. 255

Bishop described Jayeong as "clever and educated", and Gojong to be "kind" during the time she visited the palace.[85]

William Franklin Sands, a United States diplomat who came to Korea during Japan's colonisation, also spoke highly about the queen consort:

She was a politician and diplomat who overtaken the times, striving for the independence of Joseon, possessing outstanding academics, strong intellectual personality, and unbending willpower.

Early years

[edit]The young queen consort and her husband were incompatible in the beginning of their marriage. Both found the other's preferences unattractive. She preferred to stay in her chambers studying, while he enjoyed spending his days and nights drinking, attending banquets and enjoying royal parties. The queen, who was genuinely concerned to understand affairs of state, immersed herself in philosophy, history, and science books of a kind normally reserved for yangban men. Court officials noted that the queen consort was highly selective in choosing who she associated with and confided in.

Her first pregnancy came five years after marriage, at the age of 21, and ended in despair and humiliation when her infant son died shortly after birth. She lost all her children apart from Yi Cheok, born when she was 24.[86] His older sister was born when the queen consort was 23, but died and with a birth of two sons followed Yi Cheok's birth. They were born respectively during the queen consort's 25th and 28th years, and neither survived. These difficulties experienced in bearing healthy children may reflect in part the stresses of family and political relationships. There were no pregnancies after the age of 28, which was earlier than some other royal wives whose child-bearing ended in around their early thirties.[87]

Korean politics had resulted in the deaths of many of the queen consort's immediate relatives. In August 1866, the year of the royal marriage, there was an armed skirmish between the French Admiral Roze and the Korean troops at Ganghwa Island.[88] In 1876, the process leading to the Treaty of Ganghwa soured the relationship of Heungseon Daewongun with his son. As that relationship deteriorated, the king's father made death threats against the queen consort. Her mother was assassinated in 1874 in a bombing incident, along with her adoptive older brother, Min Seung-ho.[89][90][91][92] During the Insurrection of 1882 and the 1884 coup, some of the queen consort's relatives were killed. The queen consort herself was exposed to personal danger as the attempts on her life and safety demonstrate.

The royal couple's surviving son, Sunjong, was a sickly child, frequently catching illnesses and convalescing for weeks.[citation needed] The Empress cared personally for the Crown Prince and sought help from shamans and monks. The latter received rewards for blessings. Had the Crown Prince died, his rights would have devolved to the offspring of a royal concubine. The Crown Prince and his mother shared a close relationship despite her strong personality.[93]

Later years

[edit]Gojong and his wife shared an affection during the later years of their marriage. Gojong was chosen to become King not because of his astuteness (lacking because he was never formally educated) or because of his bloodline (which was mixed with courtesan and common blood), but because the Pungyang Jo clan had wrongly assumed they could control him indefinitely through his father. Eventually Gojong was pressured by his Min advisers to seize control of the government, which he did. In attending to responsibilities of state, he depended frequently on his capable wife for the conduct of international and domestic affairs. In so doing, Gojong came to appreciate his wife's wit, intelligence, and ability to learn quickly. As the problems of the kingdom increased, Gojong relied even more on his wife.

By the years of modernisation of Joseon, it is safe to assume that Gojong had come to love his wife. They began to spend much time with each other, privately and officially. His affection for her was enduring. When Daewongun regained political power after the death of the queen consort, he presented a proposal with the aid of certain Japanese officials posthumously to lower his daughter-in-law's status from queen consort to commoner.[94] The official degree of degradation issued against the dead queen was regarded as a fraud and was rescinded by the issuers not long afterwards, in the meantime having been rejected by the US and all legations bar one.[95] On 15 October 1895, a few days after the murder, when the terrified King and the Crown Prince were confined to the palace, still believing that the queen consort had managed to run away from her pursuer, Daewongun issued in the King's name an edict that she was to be divorced for desertion and that the King would remarry.[96]

Gojong bitterly refused to cooperate. Instead, he raised his deceased wife's position to Bin (빈; 嬪);[97][98] the title being the first rank of Women of the Internal Court. He erected a spirit shrine to her in the inner palace enclosure. It was connected to the house by a decorated gallery.[99]

After Gojong's father died in early 1898, he did not attend the funeral due to their strained relationship in consequence of the queen consort's murder and Daewongun's subsequent actions. It is said that Gojong's cries at the death of his father were heard over the palace walls.[100][101]

Residence

[edit]The royal couple had three palaces available to them in Seoul. They chose to reside in the Northern Palace, Gyeongbokgung Palace, where ultimately the queen's assassination took place. After that, and following his return from sanctuary in the Russian Legation, Gojong refused to live in Gyeongbokgung Palace.[102] In life, the queen consort used a series of inter-communicating small rooms separated by sliding panel doors. These rooms were approximately 8 foot (2.4 metres) square. This palace also contained the great Throne Hall, Geunjeongjeon.

Assassination

[edit]

The Eulmi Incident

[edit]In the immediate run-up to her death, the queen consort had allied herself with Russian interests to counterbalance Japanese influence. She was perceived by the Japanese as an important hostile target.[6] Her assassination took place in the early hours on 8 October 1895 within the king's private quarters, in an attack known in Korea as the Eulmi Incident (을미사변; 乙未事變). A few court ladies also shared her fate due to the Japanese mistaking them for the queen. The attack was organized by Miura Gorō and carried out by over fifty Japanese agents.[103] The royal palace was in disarray after the ordeal, but Gojong ordered a eunuch to search for the queen's remains: only a singed finger bone was later found.[104][103][105]

Funeral procession and tomb

[edit]

On 13 October 1897, Gojong (with Russian support) regained his throne, and spent a fortune (70,000 dollars in United States money of the day[106]) to have his beloved queen's remains properly honored and entombed. On 22 November 1897,[107] her mourning procession included 5,000 soldiers, 650 police, 4,000 lanterns, hundreds of scrolls honoring her, and giant wooden horses intended for her use in the afterlife. The honors Gojong placed on her at her funeral were a recognition of her diplomatic and heroic efforts on behalf of Korea against the Japanese. They were also a statement of his own love for her. The recovered remains are in her tomb located in Namyangju, Gyeonggi, South Korea.[108]

Aftermath

[edit]

Gojong left the palace in 1896 and took refuge on 11 February for a year in the nearby armed Russian Legation where he remained safe with the Crown Prince until February 1897.[109] Meanwhile, the third stage of the Gabo Reforms were hugely unpopular including because Korean men were ordered to cut off their topknots. By the time Gojong returned to the palace, the temporary ascendancy of Japanese interests (a pro-Japanese cabinet and the Japanese-instigated Gabo Reform) following the Sino-Japanese war and the assassination of the queen consort was over. This was because of popular anti-Japanese sentiment and the fact that the King had been in the effective control of the Russians.[6] In the longer term, these tensions resulted in Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War.[110] In 1910, the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty established Korea's status as a Japanese colony. This status lasted between 29 August 1910 and 15 August 1945.

Proclaimed titles

[edit]

On 6 January 1897, Gojong changed the queen consort's posthumous name to "Queen Munseong" (문성왕후, 文成王后), and altered her funeral location to Hongneung. Officials advised that the name was too similar to King Jeongjo's Munseong temple name, therefore on 2 March 1897 Gojong changed the name to "Myeongseong". That name is not to be confused with Queen Myeongseong of the Cheongpung Kim clan, King Hyeonjong's wife.[97][111][112]

Gojong proclaimed a new reign and became Emperor Gwangmu on 13 October 1897. The queen's title was also changed to "Empress Myeongseong" (명성태황후; 明成太皇后), that same month adding Tae (태; 太), meaning Great, to her posthumous title.[113][114]

Memorials

[edit]

In the place where the limited physical remains of the queen consort were found after cremation, a marker of the site was erected by 1898. Gojong built a spirit house for her, now demolished, a photograph of which survives from 1912. The mortal remains of the couple are interred together at the Joseon Royal tombs complex at Hongyuneung (홍유릉), Namyangju.

Photographs and illustrations

[edit]Photographs of Myeongseong

[edit]

Although documents note that the queen consort was in an official royal family photograph, its whereabouts are unknown. Another royal family photograph depicting Gojong, Sunjong, and Crown Princess Min exists, but it was taken after the Empress' death. Shin Byong-ryong, a professor at Konkuk University, has stated his belief that the lack of photos of the queen consort derives from her constant fear of being recognizable to the public. Myeongseong's political prominence has led many to believe that a photo of her must have existed at some point in history. Others have suspected that the Japanese government may have removed all evidence of this kind after her assassination. Some further speculated that the Japanese themselves may have kept a photo of her.[115] As at 2022, it remains questionable whether any contemporary image of her in photographic form survives.[116]

In 2003, KBS News reported that an alleged photograph of the queen consort had been disclosed to the public.[115] The photograph was said to have been preserved as a family heirloom upon its purchase by the grandfather of Min Su-gyeong. In the photo, a woman is accompanied by a retinue at her rear. Experts have stated that the woman was clearly of high rank and possibly the wife of a bureaucrat. The woman's clothing appeared to be of the kind worn only by the royal family but her outfit did not display the embroideries expected to decorate the apparel of the Empress. Some have further speculated that the figure may have been a high-ranking maidservant of the Empress.[117][115]

Alleged portraits

[edit]At the time of her assassination, an oil painting by Italian artist Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766) was alleged to be a portrait of the Empress. However, the painting was too early and was subsequently discovered to be a portrait of Xiang Fei, a concubine of the Qianlong Emperor during 18th century Qing Dynasty.[118]

In August 2017, a gallery exhibition held by Daboseong Ancient Art Museum in Central Seoul displayed a portrait of a woman said to be Empress Myeongseong. The woman is seen wearing a white hanbok, a white hemp hat, and leather shoes. She sits on a western-style chair. Kim Jong-chun, director of Daboseong Gallery, stated that when the portrait was examined, "Min clan" was written above the face side, and "portrait of a Madame" had been inscribed on the back. Subsequently, based on infrared research by the gallery, scholars and an art professor doubt the identification of the woman as being the queen consort.[119]

Japanese illustration

[edit]

On 13 January 2005, history professor Lee Tae-jin (이태진; 李泰鎭) of Seoul National University unveiled an illustration from an old Japanese magazine he had found at an antique bookstore in Tokyo. The 84th edition of the Japanese magazine Fūzokugahō (風俗畫報) published on 25 January 1895 has a Japanese illustration of Gojong and the queen consort receiving Inoue Kaoru, the Japanese chargé d'affaires.[117] The illustration is marked 24 December 1894 and signed by an artist with the surname Ishizuka (石塚). It also has an inscription: "The [Korean] King and Queen, moved by our honest advice, realize the need for resolute reform for the first time." Lee considered that the depiction of clothes and background are sufficiently detailed to suggest that it was drawn at the scene. Both the King and Inoue are shown looking at the queen consort in a manner that suggests the conversation was taking place between the queen consort and Inoue, with the King listening.

Family

[edit]- Grandfather

- Min Gi-hyeon (민기현; 閔耆顯; 1751–1 August 1811)

- Grandmother

- Lady Jeong of the Yeonil Jeong clan (1773–9 March 1838); Min Gi-hyeon's third wife

- Father

- Min Chi-rok, Internal Prince Yeoseong (여성부원군 민치록; 閔致祿; 1799 – 17 September 1858)

- Mother

- Internal Princess Consort Hanchang of the Hansan Yi clan (한창부부인 한산 이씨; 1818 – 28 November 1874); Min Chi-rok's second wife

- Grandfather: Yi Gyu-nyeon (이규년; 李圭年; 1788–?)

- Grandmother: Lady Kim of the Andong Kim clan (안동 김씨; 安東 金氏; 1788–?)

- Stepmother: Internal Princess Consort Haeryeong of the Haeju Oh clan (1798 – 15 March 1833)

- Step-Grandfather: Oh Hui-sang (오희상; 吳煕常; 1763–1833)

- Internal Princess Consort Hanchang of the Hansan Yi clan (한창부부인 한산 이씨; 1818 – 28 November 1874); Min Chi-rok's second wife

- Siblings

- Adoptive older brother: Min Seung-ho (1830 – 28 November 1874);[j] son of Min Chi-gu (1795–1874)

- Adoptive sister-in-law: Lady Kim of the Gwangsan Kim clan clan (1843–1867 23 April); Min Seung-ho's first wife

- Unnamed adoptive nephew (1864–1874)

- Adoptive sister-in-law: Lady Kim of the Yonan Kim clan; 1830–11 February 1859); Min Seung-ho's second wife

- Adoptive sister-in-law: Lady Yi of the Deoksu Yi clan (1851–1 July 1919); Min Seung-ho's third wife

- Adoptive nephew: Min Yeong-ik (1860–1914); eldest son of Min Tae-ho (1834–1884)

- Adoptive sister-in-law: Lady Kim of the Gwangsan Kim clan clan (1843–1867 23 April); Min Seung-ho's first wife

- Unnamed older brother (1840–1847)

- Older sister: Lady Min of the Yeoheung Min clan (1843–1849)

- Older sister: Lady Min of the Yeoheung Min clan (1847–1852)

- Adoptive older brother: Min Seung-ho (1830 – 28 November 1874);[j] son of Min Chi-gu (1795–1874)

- Husband

- King Gojong (later "Emperor Gojong"; 9 September 1852 – 21 January 1919)

- Father-in-law: Heungseon Daewongun (21 December 1820 – 22 February 1898)

- Legal father-in-law: King Munjo of Joseon (18 September 1809 – 25 June 1830)

- Mother-in-law: Grand Internal Princess Consort Sunmok of the Yeoheung Min clan (3 February 1818 – 8 January 1898)

- Legal mother-in-law: Queen Shinjeong of the Pungyang Jo clan (21 January 1809 – 4 June 1890)

- Father-in-law: Heungseon Daewongun (21 December 1820 – 22 February 1898)

- King Gojong (later "Emperor Gojong"; 9 September 1852 – 21 January 1919)

- Children

- Son: Prince Royal Yi Choi (원자 이최; 4 November 1871 – 8 November 1871)[k]

- Unnamed daughter (13 February 1873 – 28 September 1873)

- Son: Yi Cheok, Emperor Sunjong (25 March 1874 – 24 April 1926)

- Daughter-in-law: Empress Sunmyeong of the Yeoheung Min clan (20 November 1872 – 5 November 1904) – daughter of Min Tae-ho, leader of the Yeoheung Min clan

- Daughter-in-law: Yun Jeung-sun, Empress Sunjeong of the Haepyeong Yun clan (19 September 1894 – 3 February 1966) – daughter of Marquis Yun Taek-yeong

- Son: Grand Prince Yi Deol (대군 이덜; 5 April 1875 – 18 April 1875)[l]

- Son: Grand Prince Yi Bu (대군 이부; 18 February 1878 – 5 June 1878)

In popular culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Film and television

[edit]- Portrayed by Hwang Jeong-sun in the 1959 film Daewongun and Minbi

- Portrayed by Choi Eun-hee in the 1964 film The Sino-Japanese War and Queen Min the Heroine

- Portrayed by Do Geum-bong in the 1969 film Destiny of My Load

- Portrayed by Yoon Jeong-hee in the 1971 film The Women of Gyeongbokgung

- Portrayed by Kim Yeong-ae in the 1973 MBC TV series Queen Min

- Portrayed by Do Geum-bong in the 1973 film Three Days of Their Reign

- Portrayed by Kang Soo-yeon and Kim Yeong-ae in the 1982 KBS1 TV series Wind and Cloud

- Portrayed by Kim Ji-sook in the 1989–1990 KBS2 TV series Wind, Clouds, and Rain

- Portrayed by Kim Hee-ae in the 1990 MBC TV series 500 Years of Joseon: Daewongun

- Portrayed by Ha Hee-ra in the 1995–1996 KBS1 TV series Dazzling Dawn

- Portrayed by Moon Geun-young, Lee Mi-yeon and Choi Myung-gil in the 2001–2002 KBS2 TV series Empress Myeongseong.

- Portrayed by Soo Ae in the 2009 film The Sword With No Name.[120]

- Portrayed by Kang Soo-yeon in the 2006 film Hanbando

- Portrayed by Seo Yi-sook in the 2010 SBS TV series Jejungwon.

- Portrayed by Ha Ji-eun in the 2014 KBS2 TV series Gunman in Joseon.

- Portrayed by Choi Ji-na in the 2015 KBS2 TV series The Merchant: Gaekju 2015

- Portrayed by Lee Yoon-jeong in the 2015 film The Sound of a Flower

- Portrayed by Kim Ji-hyeon in the 2019 SBS TV series Nokdu Flower

- Portrayed by Park Jung-yeon in the 2020 TV Chosun TV series Kingmaker: The Change of Destiny

- Portrayed by Cha Ji-yeon in the 2021 film Lost Face

Musicals

[edit]See also

[edit]- Society in the Joseon dynasty

- Political factions during the Joseon dynasty

- Japanese Occupation of Gyeongbokgung Palace

- Joseon Dynasty

Notes

[edit]- ^ Current location: 250-1 Neunghyeon-dong, Cheorwon County, Gangwon Province, South Korea

- ^ Her name is also romanized "Empress Myungsung".

- ^ In the lunar calendar, the Empress was born on the 25th day of the 9th month of the 2nd year of the reign of King Cheoljong of Joseon, and died on the 20th day of the 8th month of the 32nd year of the reign of King Gojong of Korea (her husband)

- ^ In Kim Dong-in's historical novel Spring of Unhyeongung, Empress Myeongseong is said to be a filial child when her father Min Chi-rok was lying in bed due to illness.

- ^ The Daewongun's wife is the Princess Consort to the Prince of the Great Court.

- ^ Styled as "Her Majesty, the Central Hall" (jungjeon mama, 중전마마, 中殿媽媽).

- ^ Palace hall names were eventually used to differentiate Gojong’s three concubines who had the same surname and title: Royal Consort Yi Gwi-in of the Yeongbo Hall (영보당 귀인 이씨), Royal Consort Yi Gwi-in of Naean Hall (내안당 귀인 이씨), and Royal Consort Yi Gwi-in of the Gwanghwa Hall (광화당 귀인 이씨)

- ^ It was said that the Empress Myeongseong disguised herself in advance by acting as Hong Kye-hun's sister, and was carried on the back of Hong Kye-hun. She was able to escape the city and go to Yeoju to hide.

- ^ The hospital was renamed "Jejungwon" on 23 April 1885. Currently, this would be the future Yonsei University & Severance Hospital.

- ^ Younger brother of her mother-in-law, Grand Internal Princess Consort Sunmok (Gojong's mother)

- ^ Died from complications of imperforate anus; was given title of Prince Royal (원자; 元子) before he died

- ^ Was also known as Grand Prince Yi Po (대군 이표)

References

[edit]- ^ Park Jong-hyo (박종효) (9 November 2004). "일본인 폭도가 가슴을 세 번 짓밟고 일본도로 난자했다" [Japanese mob tramped down her breast three times and violently stabbed her with a katana]. Shindonga (in Korean).

- ^ "Korean Women in Resistance to the Japanese". Archived from the original on 8 March 2002.

- ^ Paine, S. C. M. (2003). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge University Press. p. 316. ISBN 9780521817141.

- ^ Hulbert 1905, p. 302: The top-knot was "the distinctive mark of Korean citizenship".

- ^ a b c 아관파천 [Agwan Pacheon] (in Korean). Doosan Encyclopedia – via Naver.

- ^ a b c Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Miln 1895, chpt. 5: "She—the most powerful Korean in Korea—is content to be nameless; a sovereign with almost unlimited power, but without a nominal individuality; and to be called merely by the family name of her forefathers, and to be designated only as the daughter of her fathers, the wife of her husband, and the mother of her son."

- ^ a b Kim, Wook-Dong (2019). Global Perspectives on Korean Literature. Ulsan: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 36. ISBN 9789811387272.

- ^ Quinones, C. Kenneth (December 1980). "The Kunse Chosŏn Chŏnggam and Modern Korean Historiography". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 40 (2): 511. doi:10.2307/2718991. JSTOR 2718991.

- ^ Choe Ching Young. The Rule of the Taewŏn’gun, 1864-1873: Restoration in Yi Korea. Cambridge, Mass.: East Asian Research Center, Harvard University, 1972.

- ^ Some sources say that she was born 25 September; the date discrepancy is due to the difference in the calendar systems. "Queen Min". Archived from the original on 17 February 2006.

- ^ The house she was born in was built in 1687, in the 13th year of King Sukjong, and was rebuilt in 1975 and 1976. In 1904, a stone monument inscribed with the handwriting of her husband Gojong (called the Tangangguribi) was erected on the alleged site used by her for study."Place 2". myhome.shinbiro.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ The House of Gamgodang is that in which she lived from her birth until she was eight. In 1687, a hut for the king's father-in-law, the father of Queen Inhyeon, Min Yu-jung was built. Only the main building remains today, but the building was restored to its natural state in 1995. In the room where the empress studied as a child, a monument was erected inscribed with the words "Empress Myeongseong Tangangguri" (the village where Empress Myeongseong was born) to commemorate her birth. "Home > Tourism> Historical Relic". Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ The inscription, measuring 250 by 64 by 45 cm3, which her husband Gojong erected in 1904 (The Gwangmu Emperor's 8th year (Gapjin), 5th month, 1st day), read 明成皇后誕降舊里碑 명성황후탄강구리비 Myeongseong Hwanghu Tangangguribi The Stone Tablet for The Empress Myeongseong's Birthplace, her Former Village. "명성황후탄강구리비(明成皇后誕降舊里碑)". minc.kr.

- ^ a b c d e f "Queen Min". Global Korean Network of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 17 February 2006. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ Han 2001, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Han 2001, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Based on the existing (lunar) calendar of the time. See "Queen Min". Archived from the original on 17 February 2006. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- ^ a b c Yi Kyŏng-jae (이경재) (2003). 한양이야기 [Hanyang History] (in Korean). Garam (가람기획). p. 234.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce. Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- ^ a b Griffis 1897, p. 467.

- ^ Simbirtseva, Tatiana M. (8 May 1996). "Queen Min of Korea: Coming to Power". Global Korean Network of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 17 February 2006.

- ^ 음서로 벼슬에 올라 장악원과 사도시의 첨정을 지냈으며, 딸이 왕비로 간택되면서 영의정에 추증되고 여성부원군(驪城府院君)에 추봉되었다. [1]

- ^ Han 2001, pp. 24–27.

- ^ 지두환, 241쪽 (Translation: Ji Du-hwan, pg. 241)

- ^ 임중웅, 370 ~ 371쪽에서 (Translation: Im Jung-eung, pg. 370–371)

- ^ Han 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie (16 May 2019). "Biography of Queen Min, Korean Empress". ThoughtCo.

- ^ Miln 1895, chpt. 5: In line with Korean custom: "Korean wives have one rather desirable prerogative—a prerogative which the wives of China do not share with them, nor I fancy, do the wives of Japan. A Korean man cannot house his concubines or second-class wives under the roof that shelters his true or first wife, without her permission."

- ^ Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (1895). Corea or Cho-sen: The Land of the Morning Calm. London: William Heinemann. chpt. 10.

- ^ Griffis, William Elliot (1912). A Modern Pioneer in Korea: The Life Story of Henry G. Appenzeller. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company. p. 58.

- ^ Hulbert 1905, pp. 216, 221: On the alleged basis that the Japanese letter addressed the Koreans disrespectfully not as equals.

- ^ Hulbert 1905, pp. 219–221.

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 437: By means of thousands of stone monuments set up at cross-roads and markets that he ordered to be inscribed with slogans. Even sticks of ink were sloganised.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Bird 1898, p. 23.

- ^ Hirano, Kenichiro. "Interactions among Three Cultures in East Asian International Politics during the Late Nineteenth Century: Collating Five Different Texts of Huang Zun-xian's "Chao-xian Ce-lue" (Korean Strategy)" https://web.archive.org/web/20150402100550/http://dspace.wul.waseda.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2065/789/1/20031113_hirano_eng.pdf Retrieved 15 September 2023

- ^ Described by Hirano as "Huang (1848–1905, alias Gong-du, a native of Jia-ying county, Guangdong province and a Hakka)"

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 430.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, p. 70.

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 432.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 73–74.

- ^ 황현, 《역주 매천야록 (임형택 외 역, 문학과지성사, 2005) 176"페이지 [Hwang Hyeon, 《Translated by Maecheon Yarok (translated by Lim Hyeong-taek et al., Munhwagwajiseongsa, 2005), page 176]

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, p. 74.

- ^ a b Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Griffis 1897, pp. 438–440.

- ^ Hulbert 1905, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Hwang 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Hwang 2011, p. 56.

- ^ 고종실록 19권, 고종 19년 6월 10일 갑자 7번째기사.

- ^ 임중웅, 374 ~ 375쪽

- ^ 지두환, 245쪽

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 441: Events to 13 September including the arrest are in a telegram to the New York Tribune of 2 October.

- ^ Griffis 1897, pp. 446–447.

- ^ Dennett 1922, pp. 477–478.

- ^ Dennett 1922, p. 481.

- ^ Dennett 1922, p. 478.

- ^ Hulbert 1905, pp. 235–238.

- ^ Dennett 1922, p. 479.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 450.

- ^ At page 166 in Korea and Japan (May 1905) in The Korea Review, Vol. 5 No. 5, May 1905 (ed) Homer B. Hulbert https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/58243/pg58243-images.html Retrieved 15 September 2023

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 451.

- ^ Dennett 1922, p. 486: The Progressive coup participant Kim Ok-kiun (modern designation Kim Ok-gyun) was lured to Shanghai by his "friend" then murdered there. The involvement of Chinese General Yuan Shi Kai was suspected (at least by the Americans). The General brought the body back to Korea in a Chinese war vessel and the murderer was received at court. The corpse was cut up and pieces were displayed in various parts of Korea.

- ^ Dennett 1922, p. 486.

- ^ Bird 1898, p. 20.

- ^ see Dangojeon, under History

- ^ Bird 1898, p. 25.

- ^ a b Griffis 1897, p. 447.

- ^ a b Neff, Robert (30 May 2010). "Korea's modernization through English in the 1880s". The Korea Times. Seoul, Korea: The Korea Times Co. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ See Gallery photograph of Appenzeller's school in 1887.

- ^ 이화학당 梨花學堂 [Ewha Hankdang (Ewha Academy)] (in Korean). Nate/ Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.

1887년 학생이 7명으로 늘어났을 때, 명성황후는 스크랜튼 부인의 노고(勞苦)를 알고 친히 '이화학당(梨花學堂)'이라는 교명을 지어주고 외무독판(外務督辦) 김윤식(金允植)을 통해 편액(扁額)을 보내와 그 앞날을 격려했다. 당초에 스크랜튼 부인은 교명(校名)을 전신학교(專信學校, Entire Trust School)라 지으려 했으나, 명성황후의 은총에 화답하는 마음으로 '이화'로 택하였다.이는 당시에 황실을 상징하는 꽃이 순결한 배꽃〔梨花〕이었는데, 여성의 순결성과 명랑성을 상징하는 이름이었기때문이다.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, p. 63: See An Chongbok quoted in Chonhak Mundap and Chonhakko.

- ^ Griffis 1897, p. 453.

- ^ Bird 1898, p. 19.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, p. 49.

- ^ Korea: Its Land, People and Culture of All Ages 1960, pp. 76–80.