Naito Parkway

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Facing northwest on the Steel Bridge | |

| Former name(s) | Front Street Front Avenue |

|---|---|

| Part of | |

| Namesake | Bill Naito |

| Owner | Portland Bureau of Transportation |

| Length | 3.2 mi (5.1 km)[1] |

| Location | Portland, Oregon, U.S. |

| From | SW Barbur Blvd |

| Major junctions | |

| To | NW Front Ave |

Naito Parkway is a major thoroughfare of Portland in the U.S. state of Oregon. It was formerly known as Front Avenue and Front Street and was renamed in 1996 to honor Bill Naito. It runs between SW Barbur Boulevard and NW Front Avenue, and adjacent to Tom McCall Waterfront Park through Downtown Portland.

Route description

[edit]Starting from the south, SW Naito Parkway begins at its interchange with Barbur Boulevard. Up to that point, Barbur serves as Oregon Route 99W (OR 99W) and OR 10, but Naito takes over this designation north of the interchange. Continuing northbound, the parkway has an interchange with the Ross Island Bridge, part of U.S. Highway 26 (US 26).

The street then passes over Interstate 405 (I-405), including ramps for the Marquam Bridge, and into Downtown Portland. After passing Harbor Drive, which provides an I-5 southbound connection, the parkway runs adjacent to Tom McCall Waterfront Park through most of downtown, with connections to the Hawthorne and Morrison bridges.[1] The Morrison Bridge provides a second connection to I-5. Between these two bridges in the median of Naito is Mill Ends Park which is, according to some, the world's smallest park.[2]

Naito then passes by the Portland Saturday Market and under the Burnside Bridge, at which point it becomes NW Naito Parkway. Next, it has an interchange with the Steel Bridge, where it loses its Highway 99W designation, as that route crosses over the bridge to continue on N Interstate Avenue. The parkway continues north to pass under the Broadway and Fremont bridges. It then passes through a level railroad crossing that serves as a passenger and freight access point to Union Station. Naito Parkway ends just after the Fremont Bridge, at its intersection with NW 15th Avenue, although the street itself continues in a northwest direction as NW Front Avenue.[1]

Transportation

[edit]Several radial TriMet bus lines serving southwestern suburbs of Portland access Downtown via the southern portion of Naito Parkway. These lines include:

All routes merge northbound onto Naito from Barbur Boulevard and turn west after entering Downtown to provide connection to the Portland Transit Mall. Routes then return to Naito southbound. These routes also connect to the Portland Streetcar at Naito and Harrison Street.[3]

Line 16, a radial line serving Sauvie Island and the far northern neighborhoods of Linnton and St. Johns, accesses Downtown via the north end of Naito, turns west on Oak Street to provide connection to the Transit Mall, and then returns to Naito northbound.[3]

Starting in 2015, the Portland Bureau of Transportation began the Better Naito project, closing one northbound lane of Naito during the summer months in order to convert it into a cycle track and pedestrian area that runs the length of Tom McCall Waterfront Park.[4] The bureau plans to make these changes permanent and year-round by 2020, but has decided to keep the temporary cycle track in place from January 2019 until permanent construction is completed.[5][6]

History

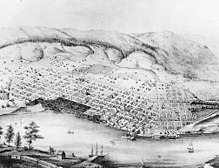

[edit]The beginning of Naito Parkway coincided with the birth of Portland, when William P. Overton built his home along the waterfront in 1841.[7] In these early days of the city, Naito was known as Front Street, and was the center of the downtown commercial core.[8] Front consisted of a large levee, which was considered by many community members to be a public street, although a court ruling found it to be private in 1862.[7]

The first school in Oregon was housed in a small wooden building on Front and Taylor Street, which started in 1845 and was led by Oregon's first practicing teacher and doctor, Ralph Wilcox.[9] The city's first brick building was constructed on the west side of Front in 1853, when William S. Ladd commissioned Absalom B. Hallock to build his liquor and wine store. Shortly after, Hallock was commissioned to add a second floor to the building, which was used as the first location of the Ladd and Tilton Bank.[10]

The narrow strip of land between the Willamette River and Front's downtown section was occupied by a series of wharves, many of which were open to public use. This proximity to the river made Front an economic hub for the city. Many brick commercial buildings were constructed on the west side of Front, including the 1885 Fechheimer & White Building[11] and the 1857 Hallock–McMillan Building, which stands today as Portland's oldest extant building.[12]

Before dawn on December 22, 1872, a fire was discovered at a Chinese laundry between Alder and Morrison Street on the east side of Front Street. Due in part to windy conditions and flammable trash piled up between the pilings of the waterfront buildings, the fire spread quickly and engulfed buildings on both sides of the block.[13] The fire destroyed two city blocks before it was extinguished. The city officially blamed the Chinese for the fire, and there were reports that a group of white residents had drowned three Chinese men in the Willamette during the blaze.[14] Portland Police also rounded up Chinese men at gunpoint and forced them to work water pumps to fight the fire. In spite of official and popular blame being placed on Chinese residents, it is now thought that the fire was more likely an act of racially-motivated arson.[13]

On August 2 of the following year, the Great Fire of 1873 started at a furniture store on Front.[9] The area damaged by the 1872 fire acted as a buffer, aiding in containment efforts.[15] In spite of this, over 20 blocks were destroyed.[16] The prevalence of wood as a building material was a large factor in the fire's spread, and efforts to rebuild the affected area heavily employed brick and iron in an intentional effort to improve construction quality.[9] Builders also became increasingly focused on architectural aesthetics, and by the 1880s, both sides of Front's commercial core were lined with multi-story buildings featuring decorative cast iron fronts and wooden colonnades.[10]

Repeated floods of the Willamette, including a major one in 1894, encouraged commercial development to move further away from the river.[10] In addition, the arrival of the railroad meant that the river was no longer the primary means of shipping. By the turn of the century, much of the river's shipping traffic had moved north, the commercial core had migrated west to Fourth and Fifth Avenue, and many buildings along Front sat abandoned.[17]

Many of the wharves along Front were torn down in 1929 in order to build a seawall and sewer interceptor.[7] The seawall remedied problems with flooding, but loss of the wharves substantially diminished commercial purpose for the area.[10]

The Great Depression led to further decline in Front's commercial importance, and many of the multi-story buildings that remained occupied were vacant except for the ground floor storefronts. As part of an effort to rejuvenate the street, the city built the Portland Public Market in 1933.[10]

Front Street was renamed Front Avenue in 1935.[18]

The 1942 opening of Harbor Drive cut Front Avenue completely off from the river, and replaced it as the main thoroughfare along the waterfront.[8] Front was also widened as part of this project. All 79 buildings between Front and the river were torn down as a result, including the Portland Public Market.[19]

By 1968, the Portland Bureau of Planning recommended the elimination of Harbor Drive, in order to expand the city's park system and give the public access to the waterfront.[20] Interstate 5 was completed in 1964 on the east bank of the river, and I-405 was completed on the west side in 1969. Completion of the Fremont Bridge in 1973 completed the city's current freeway loop, drastically reducing the need for Harbor Drive as a thoroughfare.[8] Harbor was closed in 1974 and demolition began to make way for Tom McCall Waterfront Park, once again making Front Avenue the nearest street to the west-side waterfront.[17]

In 1987, Skanner owner Bernie Foster led a push to change the street's name to honor civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Over 200 surveyed property owners opposed the change, while only nine supported it. Foster eventually succeeded in renaming Union Avenue to Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd.[21]

In 1996, the city renamed the street Naito Parkway to honor local investor, philanthropist, and civic leader Bill Naito.[22] The change went into effect only a few months after Naito's death, against a city code requiring that a person be deceased for at least five years before a street can be named after them.[23]

Events

[edit]Naito Parkway is often partially closed or otherwise modified to accommodate events at Tom McCall Waterfront Park,[24] including the Waterfront Blues Festival, Rose Festival, and the Oregon Brewers Festival.

The Rose Festival's Starlight Run uses Naito as a starting point, and also used it as a finish point in 2019.[25]

Naito has been used as a starting and finishing point in the Portland Marathon, and has been involved in media attention regarding mishaps in the race. In 2018, runners approaching the final stretch were delayed by a freight train crossing at the Steel Bridge.[26] In 2019, runners went off-route after missing a turn onto the Ross Island Bridge and continuing south on Naito.[27]

Notable landmarks

[edit]Naito Parkway runs adjacent to many notable buildings and other landmarks, particularly as it passes through the Skidmore/Old Town Historic District.[28]

- National University of Natural Medicine, 2828 SW Naito Parkway

- Salmon Street Springs, SW Naito Parkway & Salmon Street

- World Trade Center buildings 2 & 3, SW Naito Parkway & Salmon Street

- Mill Ends Park, SW Naito Parkway & Taylor Street

- Hallock–McMillan Building (built 1857), 237 SW Naito Parkway

- Fechheimer & White Building (built 1885), 233 SW Naito Parkway

- Smith's Block (built 1872), 111 SW Naito Parkway

- Portland Saturday Market Pavilion, SW Naito Parkway & Ankeny Street

- Bill Naito Legacy Fountain SW Naito Parkway & Ankeny Street

- Skidmore Block Building (built 1889) & White Stag sign, 70 NW Couch Street

- Japanese American Historical Plaza, NW Naito Parkway & Couch St

- Centennial Mills (built 1911), 1362 NW Naito Parkway

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Naito Parkway" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ Young, Amalie (May 6, 2001). "One Step and You've Left Mill Ends Park". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Portland City Center (PDF) (Map). TriMet. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Portland Bureau of Transportation. "Better Naito: A New Way to the Waterfront". City of Portland. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Better Naito forever?". Portland, Oregon: KOIN-TV. July 25, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Theen, Andrew (August 8, 2019). "Northbound Naito Parkway will have one lane for cars forever". The Oregonian. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Reed, Henry (June 1, 1941). "Cavalcade of Front Avenue". Ernie Bonner Collection. Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library. Paper 119. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c Adopted West Quadrant Plan. City of Portland. March 5, 2015. p. 10. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Scott, Harvey Whitefield (1890). History of Portland, Oregon: with illustrations and biographical sketches of prominent citizens and pioneers. Syracuse, NY: D Mason & Co. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Ballestrem, Val C. (December 3, 2018). Lost Portland Oregon. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 64–67. ISBN 9781439665930. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Portland Bureau of Planning (October 6, 2008). "Revised Documentation, National Historic Landmark Nomination: Skidmore/Old Town Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ Brink, Benjamin (February 13, 2010). "Portland's oldest buildings downtown offer a peek into the past". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Fairchild, Jim (January 14, 2011). "The Portland Riverfront Fire of 1872". Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Chandler, J. D. (November 12, 2013). Hidden History of Portland, Oregon. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 9781625846679. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Fire Area, Portland, 1873". Oregon History Project. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Firefighting in Portland Through the Years". City of Portland. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Killen, John (June 18, 2015). "Throwback Thursday: In 1940s, Portland gained a freeway, lost old but impressive buildings". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ MacColl, E. Kimbark (1979). The Growth of a City: Power and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1915 to 1950. Portland, Oregon: The Georgian Press Company. p. 512. ISBN 0-9603408-1-5.

- ^ Bonner, Ernest (2003). "Widening Front Avenue". Ernie Bonner Collection. Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library. pp. 5–6. Paper 321. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "1952 to 2001". Archives & Records Management. Office of the City Auditor. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Parks, Casey (January 10, 2019). "Twenty-five years after corridor's controversial renaming, Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard is a map mainstay". The Oregonian. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ Orloff, Chet. "William Sumio Naito (1925–1996)". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Gomez, Cynthia Carmina (April 29, 2019). "Process and Privilege". Oregon Humanities. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ Azar, Kellee (April 27, 2016). "Lane closure for festivals begins Monday on Naito Parkway". KATU 2. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ "New start time and start location announced for Rose Festival's Starlight Run". Fox 12. April 12, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ San Roman, Katie (December 4, 2018). "It's Not a Sprint, It's the Portland Marathon". The Bridge. Portland Community College. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Lorge Butler, Sarah (October 9, 2019). "New Portland Marathon is Mostly a Success". Runner's World. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Skidmore/Old Town Historic District Design Guidelines". City of Portland. Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. Retrieved October 25, 2019.