Pari Khan Khanum

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Pari Khan Khanum پریخان خانم | |

|---|---|

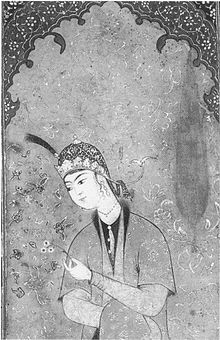

Painting of a seated princess, most likely Pari Khan Khanum[1] | |

| Born | August 1548 Ahar, Iran |

| Died | 12 February 1578 (aged 30) Qazvin, Iran |

| Betrothed | Badi-al Zaman Mirza Safavi |

| Dynasty | Safavid |

| Father | Tahmasp I |

| Mother | Sultan-Agha Khanum |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

Pari Khan Khanum (Persian: پریخان خانم, romanized: Pariḵān Ḵānom; August 1548–12 February 1578) was a Safavid princess, daughter of the second Safavid Shah, Tahmasp I and his Circassian consort, Sultan-Agha Khanum. From an early age, she was well-loved by her father and was allowed to partake in the court activities, gradually becoming an influential figure who attracted the attentions of the prominent leaders of the militant Qizilbash tribes.

She played a central role in the succession crisis occurring after her father's death in 1576. She was able to eliminate her brother Haydar Mirza and his supporters and enthrone her favoured candidate, Ismail Mirza, as Ismail II. However, despite her expectations, Ismail curtailed her power and put her in a house arrest. He died suspiciously in 1577 from poisoning, and Pari Khan may have been the mastermind behind his assassination.

With her endorsement, her elder brother Mohammad Khodabanda was chosen as Ismail's successor. Mohammad was almost blind, and this fact made him a suitable choice for Pari Khan, who expected to lead a de facto rule while Mohammad remained a figurehead. However, his influential wife, Khayr al-Nisa Begum, emerged as an opponent to Pari Khan and successfully plotted her death. Pari Khan was strangled to death on 12 February 1578, at the age of thirty.

Regarded as the most powerful woman in the Safavid history, she was praised by her contemporaries for her intelligence and competence, though in later chronicles she was portrayed as a villain who murdered two of her brothers and aspired to usurp the throne. She was a patron of poets, her most well-known beneficiary being Mohtasham Kashani who wrote five eulogies in the praise of Pari Khan. Writers of the time dedicated works to her, like Abdi Beg Shirazi and his Takmelat al-akhbar and she was compared to Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad, prophet of Islam. In a society that imposed harsh restrictions on high-class women, Pari Khan was able to take leadership of the ineffective Safavid court and gather royal followers amounting to four or five hundred.

Early life

[edit]Pari Khan Khanum was born near Ahar (in modern-day Iran) on August 1548.[2] Her father was Tahmasp I, the second shah of the Safavid dynasty. Her mother, Sultan-Agha Khanum, was the sister to Shamkhal Sultan, a Circassian noble from Daghestan.[3] Pari Khan also had a full-brother named Suleiman Mirza.[2] Contemporary chronicles describe her as intelligent, clever and intuitive, and report that these attitudes caught the interest of her father.[4] She found two role models in her aunts, Pari Khan Khanum I and Mahinbanu Sultan, both daughters of Ismail I who had political influence; Pari Khan wished to imitate and surpass them.[5]

She showed immense interest in Islamic law, jurisprudence and poetry, and excelled at them all, to the point that the Safavid historian Afushta'i Natanzi deemed her "distinct from the females".[4] Tahmasp admired her interest in the politics of the Safavid empire and she became his favourite daughter.[6][7] When she was 10 years old, she was promised to Prince Badi-al Zaman Mirza, son of Bahram Mirza, Tahmasp's younger brother.[2] Yet, as his favourite daughter, Tahmasp did not allow Pari Khan to leave the capital Qazvin for Sistan, Badi-al Zaman's abode and appanage.[2] The betrothal never culminated to a marriage.[4] Tahmasp's affection for Pari and his reliance on her advice surpassed that of his sons.[7] Consequently, her assistance and favour was coveted by the leaders of the militant tribes collectibely known as Qizilbash.[2][a]

Career

[edit]Tahmasp's succession crisis

[edit]

Despite the court's inquiries, Tahmasp never chose one of his sons as his successor, and while there was a precedent of the eldest son succeeding his father, Tahmasp's eldest, Mohammad Khodabanda, was blind and thus disqualified to rule.[9] The Qizilbash tribes and the court had split into two factions over their favoured prince: Haydar Mirza was supported by the Ustajlu tribe, along with two Safavid princes,[b] and the Georgians of the court (due to his Georgian maternal origin); while Ismail Mirza was supported by every other Turkoman tribe of the Qizilbash (e.g. Rumlu and Afshar), the Circassians, and Pari Khan herself.[11][12] Ismail was Tahmasp's second son, but he had been imprisoned for a myriad of reasons—such as pederasty—in Qahqaheh Castle since 1557; Haydar was Tahmasp's fifth son, who had become his favourite, and even was bestowed with administrative powers in times of Tahmasp's absence.[13][2] While in prison, Ismail was involved in embezzlements of Ustajlu money and had affairs with the wife of an Ustajlu commander.[13][14] As a result, Ustajlu leaders had found a better ally in Haydar.[14]

The Circassians and the Georgians both had political influence over Tahmasp and therefore were rivals of each other.[2] The foremost concern of the Qizilbash was Haydar's maternal origin, which would have potentially curb their influence in the court by an influx of Georgians entering the military ranks.[14] Pari Khan's support for Ismail may have stemmed from the desire to preserve a Turkic-Circassian dominance in the court.[15] Other probable motivations for her support include Ismail's reputation before imprisonment as a beloved and courageous prince, or that she thought by supporting him she could maintain her position and influence.[16] Pari's mother, Sultan-Agha Khanum at the request of her daughter would slander Haydar Mirza to Tahmasp and smear his image as a traitor while presenting Ismail's faction as loyal and true.[17]

On 18 October 1574 Tahmasp fell gravely ill and for two months did not recover.[2] Reportedly, Pari Khan assumed the care of her father and stayed at his bedside.[7] The shah's illness accelerated the threat of violence among the factions, so much that Haydar's supporters always closely guarded him in case of an attack.[18] At the same time, they conspired with the castellan of Qahqaheh to have Ismail murdered. Pari Khan discovered the plot and informed Tahmasp, who dispatched a group of Afshar musketeers to Qahqaheh to watch over Ismail.[2]

Although Tahmasp was mindful of the factionalism in the court, he did not appoint a successor.[18] He died on 14 May 1576, with Haydar's mother and Pari Khan at his bedside.[18] Haydar immediately declared himself the new king. On the night of Tahmasp's death, the guards of the palace (traditionally sequenced between different tribes of the Qizilbash) were from pro-Ismail faction: Rumlu, Afshar, Qajar, Bayat and Varsak, essentially imprisoning Haydar inside the palace without the support of his adherents.[2][19] Haydar Mirza apprehended Pari Khan as a way to save himself. Pari Khan ostensibly gave him her support by kissing his feet, then she swore on the Quran that she could grant him the support of her uncle, Shamkhal Sultan, and her brother, Suleiman Mirza if Haydar allowed her to leave the palace.[2] Once she had exited the court, she gave the palace keys to her uncle and Ismail supporters, who rushed into the palace and killed Haydar.[c] Afterwards, per Pari Khan's request, an envoy was dispatched to Qahqaheh to free Ismail from incarnation and bring him to the capital.[19]

Under Ismail II

[edit]

Until Ismail's arrival at Qazvin, Pari Khan established herself as the de facto leader of Iran.[2] She employed Makhdum Sharifi Shirazi, a well-known Sunni preacher, to read a khutba in the name of Ismail on the Friday prayer of 23 May 1576 in the presence of all of the foremost Qizilbash leaders, thus affirming Ismail's ascension.[2] She established a personal court of Circassians staffs and chose the calligrapher Khwaja Majid al-Din Ibrahimi Shirazi as her personal vizier.[21][d] Every morning, the Qizilbash would go to her for their concerns and petitions and Pari Khan's establishment was treated as a proper royal court.[23][2]

On 4 June 1576, Ismail arrived at Qazvin, but due to the inauspiciousness of the date (according to the astrologers), he stayed at the house of Hossein-Qoli Kholafa, leader of the Rumlu tribe, instead of heading to the palace.[2] On 1 September 1576, he was crowned king in Chehel Sotun palace as Ismail II.[13] Pari Khan expected gratitude from her brother.[24] However, Ismail was disquieted by the Qizilbash's deference to Pari Khan, and reportedly snubbed them and said to them: "Have you not understood, my friends, that interference in matters of state by women is demeaning to the king's honour?"[23] He forbade the Qizilbash leaders from seeing Pari Khan, decreased her guards and attendants, confiscated her assets and was unfriendly to her when he gave her an audience.[2] To further tarnish her reputation, Ismail spread rumours about her sexual deviancy.[25] Ismail may have also been planning to kill her, evident from a letter sent by Pari Khan to him.[13][e] The result was Pari Khan's complete isolation and absence from the chronicles throughout Ismail's reign.[27]

Ismail ruled for two years and his short tenure is described as a reign of terror.[28] Two months after his coronation, he began a purge of all his male relatives, including Badi-al Zaman Mirza, Pari Khan's betrothed and Suleiman Mirza, Pari Khan's full-brother.[13] Suleiman Mirza was killed for his aggressive behaviour which stemmed from Ismail's cold demeanour towards Pari Khan.[27] The only survivors of this purge were the blind Mohammad Khodabanda and his three young sons.[13]

Ismail's reign ended with his sudden death on 25 November 1577, with poison being suspected as the cause of death.[2] Pari Khan was presented as a main participant in Ismial's death, although the theory is unproven.[29] Still, with his death, she once again became a powerful figure in the court, with the notables of the realm obeying her decrees.[2]

Mohammad Khodabanda and death

[edit]Reportedly, after Ismail's death, Pari Khan was requested to succeed her brother, however she refused the offer.[30] The Qizilbash debated over the only two possible candidates: Mohammad Khodabanda, and Shuja al-Din, Ismail's infant son; the latter was rejected for his young age and the Qizilbash chose Mohammad Khodabanda as the new king. They then informed Pari Khan of their choice.[2] The contemporary chronicler, Hasan Beg Rumlu, records that Pari Khan was openly opposed to Mohammad's succession and tried to prevent him from arriving at Qazvin.[29] However, according to Iskandar Beg Munshi, Pari Khan considered Mohammad as the best possible candidate, as his blindness would have allowed her to maintain her power. She and the Qizilbash came to the agreement that Mohammad would only be a figurehead while she and her representatives managed the kingdom.[2]

Thus Pari Khan began her second de facto reign.[31] She released the prisoners incarcerated by Ismail and provided protection for many notable men and women; for example, she released Makhdum Sharifi Shirazi from prison and helped him escape to the Ottoman Empire.[31][29] She ordered the officials to remain in Qazvin and wait for Mohammad's arrival, however, Mirza Salman Jaberi, the former grand vizier of Ismail II, who had some responsibility in Ismail's hostility to Pari Khan, fled to Shiraz where Mohammad Khodabanda resided.[31] He warned the new shah and his forceful wife, Khayr al-Nisa Begum, of the influence of Pari Khan, causing them to openly oppose Pari Khan.[31] Mohammad sent some men to guard the state treasury which resulted in a clash between Pari Khan's supporters and his men.[31] Shamkhal Sultan then increased the guards of Pari Khan's residence, which caused more animosity between the royal couple and Pari Khan.[32] Meanwhile, many of the notables left Qazvin for Shiraz to join the shah's court.[31]

The arrival of Mohammad and Khayr al-Nisa on 12 February 1578 ended the two months reign of Pari Khan.[2] When the shah and his wife were approaching the palace, Pari Khan greeted them while sitting on a golden litter with four to five hundred guards and staff at her side.[2] Khayr al-Nisa, knowing that Pari Khan would hinder her exercise of power, began plotting her death.[2] Mohammad Khodabanda ascended the throne in the presence of all the princesses and notables, including Pari Khan.[33] Secretly, he and his wife had employed Khalil Khan Afshar, Pari Khan's childhood lala (tutor), for the murder.[34] After the festivities had ended, Pari Khan was returning to her residence with her entourage when her path was blocked by Khalil Khan. After some quarrel, she peacefully acquiesced and allowed Khalil Khan to take her to his house, where she was strangled to death.[33][f] Shamkhal Khan and Ismail's son, Shuja al-Din were also killed on the same day.[36] At the time of her death, Pari Khan had an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 tomans wealth, four to five hundred servants, and owned a house outside of the harem quarters in Qazvin.[37]

Poetry

[edit]Pari Khan was a patron of poets and also wrote poetry herself.[7] In the Takmelat al-akhbar by Abdi Beg Shirazi—which it itself was dedicated to Pari Khan[38]—there are several poems attributed to her under the takhallus (pen name) Haghighi.[39] However, according to the Iranologist Dick Davis, only one poem is proven to be written by her.[40]

Tahmasp I considered poetry as an antithesis to his piety and therefore refused to allow poets in his court.[41] Pari Khan would support talented poets during this hard period when they were not well-respected.[29] Her most distinguished beneficiary was Mohtasham Kashani, a poet from Kashan who was awarded with the title malek al-sho'ara (the poet-laurate) by her decree.[29] She ordered that all poets from Kashan should first submit their works to Mohatasham for examination before sending them to the court.[42] Mohtasham, in response to this critical moment in his career, wrote a panegyric to her.[43] Overall, his diwan (collection of poems) includes five eulogies for Pari Khan, which is a greater number than any poems Mohtasham dedicated to other royals, even Tahmasp himself.[7] In her correspondence with poets, Pari Khan would ask the poets for their response to her specific requests; for example, she once asked Mohtasham to write a reply to 80 lines of ghazal (ode) from Jami (d. 1492), one of her favourite poets.[44][42] Though Mohtasham's response to this literary project is not found in his diwan, 60 lines of ghazal with metre and rhyming schemes similar to Jami were identified by Iranologist Paul E. Losensky, confirming that Mohtasham was able to fulfil Pari Khan's request.[45]

Assessments and legacy

[edit]Pari Khan Khanum is regarded in modern historiography as the most powerful woman of her era.[33] She was able to amass a royal entourage regardless of her gender in a society that imposed far more restrictions on the high-class women than the middle and lower classes.[46] Among her contemporaries, she was eulogized as an intelligent and shrewd woman; Iskandar Beg dubbed her death as a 'brave martyrdom' and Abdi Beg Shirazi gave her titles such as 'princess of the world and its inhabitants' and 'the Fatima of the time'.[47][48] Later historians portray her more as a villainous character, condemning her for the murder of two of her brothers and aspiring to usurp the throne.[49] According to modern historian Shohreh Gholsorkhi, queenship was not Pari Khan's goal.[49] She was more confident that she was better suited to handle the affairs of the country than male princes and therefore became the indirect leader of the stale and ineffective Safavid court.[49][35]

With her downfall, Khayr al-Nesa Begum emerged as another powerful woman of the Safavid era before she was also murdered after an eighteen-month-long reign.[35] Early 20th century historians like Hans Robert Roemer and Walther Hinz portrayed Khayr al-Nesa and Pari Khan as the main culprits for the predatory nature of the Safavid court during the 1570s and 1580s.[50] However, the presence of these two women speak of other smaller female influence in the society,[51] which may suggest that Pari Khan's politicking was not only unusual, but may have been accepted.[52] However, politically influential women seem to disappear after the early years of the Safavid dynasty, suggesting that women of the court became more isolated in late Safavid history.[53]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Qizilbash is a collective name for a group of Turkic militant tribes that served the Safavid dynasty.[8]

- ^ Ibrahim Mirza, who was his cousin, and Mustafa Mirza, who was his younger brother.[10]

- ^ According to contemporary sources, Haydar dressed himself in women's clothing and hid inside the harem, but Pari Khan recognised him and ordered his death.[20][2]

- ^ Khwaja belonged to a clerical family that traditionally worked for the royal Safavid family.[22]

- ^ The letter was sent by Pari Khan as a response to Ismail's accusations. She also openly criticized his rule and condemned his systemic purge of all his male relatives.[26]

- ^ The diary of Don Juan of Persia, a well-known Iranian figure in 17th-century Spain, attests that Pari Khan was beheaded and her head was put onto a lance to be displayed publicly at the gates of Qazvin. This account contrasts with the Safavid society of the time and seems to be more a fantasy influenced by the western tradition.[35]

References

[edit]- ^ Soudavar 2000, pp. 60, 68.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Pārsādust 2009.

- ^ Szuppe 2003, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 146.

- ^ Szuppe 2003, p. 157, 168.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 147.

- ^ Aldous 2021, p. 744.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 247.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 147–148.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 57-58.

- ^ a b c d e f Ghereghlou 2016.

- ^ a b c Birjandifar 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 149-150.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 148.

- ^ a b Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 149.

- ^ Ahmadi 2021, p. 315.

- ^ Szuppe 2003, p. 153–154.

- ^ Blair 2006, p. 428.

- ^ a b Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 150.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 63-64.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 68.

- ^ a b Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 152.

- ^ Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e Ahmadi 2021, p. 316.

- ^ Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e f Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 154.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 155.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Ahmadi 2021, p. 317.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Szuppe 2003, p. 152.

- ^ Dabīrsīāqī & Fragner 1982.

- ^ Moshir Salimi 1957, p. 171.

- ^ Davis 2023, p. xxxvii.

- ^ Sharma 2017, p. 21.

- ^ a b Losensky 2004.

- ^ Losensky 2019, p. 410.

- ^ Losensky 2018, p. 573.

- ^ Losensky 2018, p. 573, 578.

- ^ Ahmadi 2021, p. 319, 317.

- ^ Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 155-156.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 52, 76.

- ^ a b c Gholsorkhi 1995, p. 156.

- ^ Mitchell 2009, p. 158.

- ^ Ahmadi 2021, p. 318.

- ^ Birjandifar 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Ahmadi 2021, p. 318, 322.

Sources

[edit]- Ahmadi, Nozhat (2021). "The status of women in Safavid society". In Matthee, Rudi (ed.). The Safavid World. New York: Taylor & Francis. pp. 310–324. ISBN 9781000392876. OCLC 1274244049.

- Aldous, Gregory (2021). "The Qizilbāsh and their Shah: The Preservation of Royal Prerogative during the Early Reign of Shah Ṭahmāsp". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 31 (4): 743–758. doi:10.1017/S1356186321000250. S2CID 236547130.

- Birjandifar, Nazak (2005). Royal women and politics in Safavid Iran (Master of Arts thesis). McGill University. OCLC 727917163.

- Blair, Sheila (2006). Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748612123. OCLC 56651142.

- Dabīrsīāqī, M.; Fragner, B. (1982). "'Abdī Šīrāzī". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume I/2: ʿAbd-al-Hamīd–ʿAbd-al-Hamīd. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-0-71009-091-1.

- Davis, Dick (2023). The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women. Washington D.C.: Mage Publishers. ISBN 9781949445053. OCLC 1107875493.

- Ghereghlou, Kioumars (2016). "Esmāʿil II". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gholsorkhi, Shohreh (1995). "Pari Khan Khanum: A Masterful Safavid Princess". Iranian Studies. 28 (3/4). Iranian Studies, vol. 28, no. 3/4: 143–156. doi:10.1080/00210869508701833. ISBN 0-85773-181-5. JSTOR 4310940.

- Mitchell, Colin P. (2009). The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric. New York: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857715883.

- Losensky, Paul (2019). "Selections from the Poetry of Muhtasham Kashani". In Khafipour, Hani (ed.). The Empires of the Near East and India. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 406–427. ISBN 9780231547840. OCLC 1049576710.

- Losensky, Paul (2018). ""Utterly Fluent, but Seldom Fresh": Jāmī's Reception among the Safavids". In d'Hubert, Thibaut; Papas, Alexander (eds.). Jāmī in Regional Contexts: The Reception of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī’s Works in the Islamicate World, ca. 9th/15th-14th/20th Century. Leiden: Brill. pp. 568–601. ISBN 9789004386600. OCLC 1076788310.

- Losensky, Paul (2004). "Moḥtašam Kāšāni". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Moshir Salimi, Ali Akbar (1957). زنان سخنور [Zanān-i Sukhanvar]. Tehran: Matbu'ati Ali Akbar Alami. OCLC 1033924945.

- Pārsādust, Manučehr (2009). "Parikhān Kānom". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Roemer, H. R. (2008). "The Safavid Period". The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–350. ISBN 9781139054980.

- Soudavar, Abolala (2000). "The Age of Muhammadi". Muqarnas. 17: 53–72. doi:10.2307/1523290. JSTOR 1523290.

- Sharma, Sunil (2017). Mughal Arcadia - Persian Literature in an Indian Court. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674975859.

- Szuppe, Maria (2003). "Status, knowledge, and politics : women in Sixteenth-Century Safavid Iran". In Nashat, Guity (ed.). Women in Iran from the Rise of Islam to 1800. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 140–170. ISBN 9780252071218. OCLC 50960739.