Pyramid of Neferirkare

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Pyramid of Neferirkare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Neferirkare Kakai | |

| Coordinates | 29°53′42″N 31°12′09″E / 29.89500°N 31.20250°E |

| Ancient name | |

| Constructed | Fifth Dynasty (c. 25th century BC) |

| Type | Step pyramid (originally) True pyramid (converted) |

| Material | Limestone[3] |

| Height | 52 metres (171 ft; 99 cu)[4] (Step pyramid) 72.8 metres (239 ft; 139 cu)[5] (True pyramid, original) |

| Base | 72 metres (236 ft; 137 cu)[4] (Step pyramid) 105 metres (344 ft; 200 cu)[5] (True pyramid) |

| Volume | 257,250 m3 (336,470 cu yd)[6] |

| Slope | 76°[4] (Step pyramid) 54°30′[5] (True pyramid) |

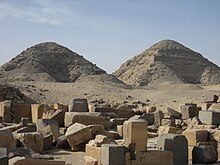

The pyramid of Neferirkare (Egyptian: Bꜣ Nfr-ỉr-kꜣ-rꜥ "the Ba of Neferirkare"[5]) was built for the Fifth Dynasty pharaoh Neferirkare Kakai in the 25th century BC.[7][a] It was the tallest structure on the highest site at the necropolis of Abusir, found between Giza and Saqqara, and still towers over the necropolis. The pyramid is also significant because its excavation led to the discovery of the Abusir Papyri.

The Fifth Dynasty marked the end of the great pyramid constructions during the Old Kingdom. Pyramids of the era were smaller and becoming more standardized, though intricate relief decoration also proliferated. Neferirkare's pyramid deviated from convention as it was originally built as a step pyramid: a design that had been antiquated after the Third Dynasty (26th or 27th century BC).[b] This was then encased in a second step pyramid with alterations intended to convert it into a true pyramid;[c] However, the pharaoh's death left the work to be completed by his successors. The remaining works were completed in haste, using cheaper building material.

Because of the circumstances, Neferirkare's monument lacked several basic elements of a pyramid complex: a valley temple, a causeway, and a cult pyramid. Instead, these were replaced by a small settlement of mudbrick houses south of the monument from where cult priests could conduct their daily activities, rather than the usual pyramid town near the valley temple. The discovery of the Abusir papyri in the 1890s is owed to this. Normally, the papyrus archives would have been contained in the pyramid town where their destruction would have been assured. The pyramid became part of a greater family cemetery. The monuments to Neferirkare's consort, Khentkaus II; and his sons, Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini, are found in the surrounds. Though their construction began under different rulers, all four of these monuments were completed during the reign of Nyuserre.

Location and excavation

[edit]

The pyramid of Neferirkare is situated on the necropolis at Abusir, between Saqqara and the Giza Plateau.[18] Abusir assumed great import in the Fifth Dynasty after Userkaf, the first ruler, built his sun temple and, his successor, Sahure inaugurated a royal necropolis there with his funerary monument.[19][20] Sahure's successor,[20] his son Neferirkare, was the second ruler to be entombed in the necropolis.[21][22][23][24] The Egyptologist Jaromír Krejčí proposes a number of hypotheses for the position of Neferirkare's complex in relation to Sahure's complex: (1) that Neferirkare was motivated to distance himself from Sahure and thus chose to found a new cemetery and redesign the mortuary temple plan to differentiate it from Sahure's; (2) that geomorphological pressures – particularly the slope between Neferirkare's and Sahure's complexes – required Neferirkare to situate his complex elsewhere; (3) on the basis of the site being the highest point, Neferirkare may have selected it to ensure his complex dominated the surrounding area and; (4) that the site may have been intentionally selected to build the pyramid in line with Heliopolis.[25][d] The Abusir diagonal is a figurative line connecting the north-west corners of the pyramids of Neferirkare, Sahure and Neferefre. It is similar to the Giza axis, which connects the south-east corners of the Giza pyramids, and converges with the Abusir diagonal to a point in Heliopolis.[28][32]

The location of the complex affected the construction process. The Egyptologist Miroslav Bárta said the location was chosen partly because of its relation to the administrative capital[e] of the Old Kingdom, Inbu-Hedj[f] known today as Memphis.[34][35] Providing that the location of ancient Memphis is accurately known, the Abusir necropolis would have been no further than 4 km (2.5 mi) from the city centre.[6] The benefit of the site being close to the city was the increased access to resources and manpower.[36] South-west of Abusir, workers could exploit a limestone quarry to gather resources for the manufacture of masonry blocks used in the construction of the pyramid. The limestone there was particularly easy to quarry considering that gravel, sand and tafl layers sandwiched the limestone into thin segments of between 0.60 m (2.0 ft) and 0.80 m (2 ft 7 in) thick making it easier to dislodge from its matrix.[37]

In 1838, John Shae Perring, an engineer working under Colonel Howard Vyse,[38] cleared the entrances to the pyramids of Sahure, Neferirkare and Nyuserre.[39] Five years later, the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius, sponsored by King Frederick William IV of Prussia,[40][41] explored the Abusir necropolis and catalogued Neferirkare's pyramid as XXI.[39] It was Lepsius who proposed the theory that the accretion layer method[g] of construction was applied to the pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasty.[45] One important development was the discovery of the Abusir papyri, found in the temple of Neferirkare during illicit excavations in 1893.[46] In 1902–1908, the Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt, working for the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft or German Oriental Society, resurveyed those same pyramids and had their adjoining temples and causeways excavated.[39][47] Borchardt's was the first, and only other, major expedition carried out at the Abusir necropolis,[47] and contributed significantly to archaeological investigation at the site.[48] His findings were published in Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Nefer-Ir-Ke-Re (1909).[49][50] The Czech Institute of Egyptology has had a long-term excavation project going at the site since the 1960s.[47][51]

Mortuary complex

[edit]

Layout

[edit]Pyramid construction techniques underwent a transition in the Fifth Dynasty.[52] The monumentality of the pyramids diminished, the design of mortuary temples changed, and the substructure of the pyramid became standardized.[52][53] By contrast, relief decoration proliferated[52] and the temples were enriched with greater storeroom complexes.[53]

These two conceptual changes had developed by the time of Sahure's reign at the latest. Sahure's mortuary complex indicates that symbolic expression through decoration became favoured over sheer magnitude. For example, Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu's complex had a total of 100 linear metres (330 linear feet) reserved for decoration, while Sahure's temple had around 370 linear metres (1,200 linear feet) dedicated to relief decorations.[54] Bárta identifies that storage space in mortuary temples expanded consistently from Neferirkare's reign onwards.[55] This was a result of the combined centralization of administrative focus onto the funerary cult, the increase in the numbers of priests and officials involved in the maintenance of the cult, and the increase in their revenues.[56][57] The discovery of considerable remains of stone vessels – mostly broken or otherwise incomplete – in the pyramid temples of Sahure, Neferirkare, and Neferefre bears testament to this development.[58]

Old Kingdom mortuary complexes consisted of five essential components: (1) a valley temple; (2) a causeway; (3) a mortuary temple; (4) a cult pyramid; and (5) the main pyramid.[35] Neferirkare's mortuary complex had only two of these basic elements: a mortuary temple which had been hastily constructed from cheap mudbrick and wood;[59][60][61] and the largest main pyramid at the site.[3] The valley temple and causeway that were originally intended for Neferirkare's monument were co-opted by Nyuserre for his own mortuary complex.[62] Conversely, a cult pyramid[h] never entered construction, as a consequence of the rush to complete the monument upon Neferirkare's death.[64] Its replacement was a small settlement and lodgings constructed from mudbrick to the south of the complex where the priests would live.[64] An enormous brick enclosure wall was built around the perimeter of the pyramid and mortuary temple to complete Neferirkare's funerary monument.[64]

Main pyramid

[edit]The monument was intended as a step pyramid, an unusual choice for a Fifth Dynasty king, given that the era of step pyramids ended with the Third Dynasty (26th or 27th century BC) centuries prior, depending on the scholar and source.[2][65][66][67] The reasoning behind this choice is not understood.[5][68] The Egyptologist Miroslav Verner considers a speculative connection between the Turin Canon's listing him "as the founder of a new dynasty"[i] and the original project, though he also considers the possibility of religious reasons and power politics as well.[68] The first build contained six carefully laid steps[60][j] of high quality limestone blocks[77][3] reaching a height of 52 m (171 ft; 99 cu).[65] A white limestone casing was to be applied to the structure,[77] but after minimal work on this was completed – extending only to the first step[65] – the pyramid was redesigned to form a "true pyramid".[60][65] Verner describes the architecture of a Fifth Dynasty pyramid:

The outer face of the first step of the pyramid core was formed by a frame made of huge blocks of dark grey limestone up to 5 m long and well bound together. Similarly, there was an inner frame built of smaller blocks, and making up the walls of the rectangular trench destined for the underground chambers of the tomb. Between the two frames pieces of poor-quality limestone had been packed, sometimes "dry" and sometimes stuck together with clay mortar and sand. ... The core was indeed modelled into steps, but these were built in horizontal layers and only the stone blocks making up the outer surface were of high quality and well joined together. The inner part of the core was filled up with only partially joined rough stones of varying quality and size.[78]

To convert the step into a genuine pyramid, the whole structure was extended outwards by about 10 m (33 ft; 19 cu) and raised a further two steps in height.[77][79] This expansion project was completed in rough order with small stone fragments intended to be cased in red granite.[60][77] The premature death of the king halted the project after only the lowest level(s) of the casing had been completed.[60][65][77] The resultant base of the structure measured 105 m (344 ft; 200 cu) on each side,[60] and, had the project been completed, the pyramid would have reached approximately 72 m (236 ft; 137 cu) in height with an inclination from base to tip of about 54°.[65] Despite the incompleteness of the structure, the pyramid – which is of comparable size to Menkaure's pyramid at Giza – dominates its surrounds as a result of the position of its site standing on a hill some 33 m (108 ft) above the Nile delta.[2][65][80]

Substructure

[edit]

The descending corridor near the middle of the north face of the pyramid serves as the entry into the substructure of Neferirkare's pyramid. The corridor begins approximately 2 m (6 ft 7 in) above ground level and ends at a similar depth below ground level.[59] It has proportions of 1.87 m (6 ft 2 in) height and 1.27 m (4 ft 2 in) width.[81] It is reinforced at the entrance and exit points with granite casing.[59] The corridor breaks out into a vestibule leading to a longer corridor which is guarded by a portcullis.[59] This second corridor has two turns, but maintains a generally eastward direction and ends in an antechamber offset from the burial chamber.[59] The roof of the corridor is unique: the flat roof has a second gabled roof made of limestone on top of it which itself has a third roof made from a layer of reeds.[59]

The burial and ante chamber's ceilings were constructed with three gabled layers of limestone. The beams disperse weight from the superstructure onto either side of the passageway, preventing collapse.[60][59] Thieves have ransacked the chambers of its limestone making it impossible to properly reconstruct,[59] though some details can still be discerned. Namely, that (1) both rooms were oriented along an east–west axis, (2) both chambers were the same width; the antechamber was shorter of the two, and (3) both chambers had the same style roof, and are missing one layer of limestone.[59]

Overall, the substructure is badly damaged: the collapse of a layer of the limestone beams has covered the burial chamber.[60] No trace of the mummy, sarcophagus, or any burial equipment has been found inside.[59][60] The severity of the damage to the substructure prevents further excavation.[5]

Mortuary temple

[edit]

The mortuary temple is located at the base of the pyramid's Eastern face.[65] It is larger than is typical for the period.[82] Archaeological evidence suggests that it was unfinished at Neferirkare's death, and was completed by Neferefre and Nyuserre.[83] For example, while the inner temple and statue niches were built from stone,[60][82] much of the rest of the temple, including the court and entrance hall, was apparently hastily completed using cheap mudbrick and wood.[60][61] This left large portions of the mortuary temple susceptible to erosion from rain and wind, where stone would have given it significant durability.[84] The site was less aesthetically impressive, although its basic layout and features remained roughly analogous to Sahure's temple.[85] Its enlarged size can be attributed to a design decision to build the complex without a valley temple or a causeway.[82] Instead, the causeway and temple, whose foundations had been constructed, were diverted to Nyuserre's complex.[60][85]

The temple was entered through the columned portico, and columned entrance hall which terminates into a large columned courtyard.[86] The columns of the hall and courtyard are made from wood arranged into the form of lotus stalks and buds.[60] The courtyard is adorned with thirty-seven such columns; these columns are asymmetrically positioned.[87] The archaeologist Herbert Ricke hypothesized that columns near the altar may have been damaged by fire and removed. A papyrus fragment from the temple archives corroborates this story.[87] A low stepped ramp in the courtyard's west leads to a transverse (north–south) corridor which leads south into storerooms and north into another smaller corridor containing six wooden columns through which the open courtyard of the main pyramid can be accessed.[86] It is in the southern storerooms that the Abusir papyri were discovered by graverobbers in the 1890s.[82] Beyond the storerooms is a gate which has another access point to the main pyramid's courtyard, and through which a second excavated south-western gate leads to Khentkaus II's complex.[64] Finally, traversing across the corridor leads directly into the inner sanctuary or temple.[60][82]

The surviving reliefs are fragmentary. Of the preserved materials, one particular block stands out as vitally important in reconstructing the genealogy of the royal family at this time. A limestone block, discovered in the 1930s by the Egyptologist Édouard Ghazouli, depicts Neferirkare with his consort, Khentkaus II, and eldest son, Neferefre.[82] It was not found at the site of the pyramid, but as a part of a house in the village of Abusir.[28]

The Abusir papyri document details concerning Neferirkare's mortuary temple at Abusir. One testimony from the papyri is that five statues were housed in the niches of the central chapel.[60] The central statue depicted Neferirkare as the deity Osiris, whereas the two outermost statues portrayed him as the king of Upper and Lower Egypt respectively.[88] The papyri also record the existence of at least four funerary boats at Abusir. Two boats are located in sealed rooms while the other two are to the north and south of the pyramid itself. The southern boat was discovered when Verner unearthed the funerary boat during excavations.[89]

Valley temple, causeway and cult pyramid

[edit]At the time of Neferirkare's death, only the foundations of the valley temple and two-thirds of the causeway to the mortuary temple had been laid.[60][90] When Nyuserre took over the site, he had the causeway diverted from its original destination to his own mortuary temple.[91] As such, the causeway travels in one direction for more than half its distance, then bends away to another for the remainder of its length.[91][92]

Neferirkare's monument has no cult pyramid.[64] Rather, the cult pyramid was replaced with a small settlement, called Ba Kakai,[k] of mudbrick lodgings for priests, south of the monument.[64][93]

The omission of these "essential"[35] elements had one significant impact.[85] Under normal circumstances, the priests tending to the deceased pharaoh's funerary cult would have lived in a 'pyramid town' built in the vicinity of the valley temple, situated on the Abusir Lake.[64][94][95] The daily records of the administration would have had their residence in the town with the priests.[85] Instead, as a result of circumstance, these documents were instead kept inside the mortuary temple.[64] This has allowed their archives to be preserved, as they would have otherwise long ago disintegrated, buried under the mud.[85] The siting of the settlement by the complex also allowed small restorative works to be conducted.[93]

Later history

[edit]Nyuserre was the last king to build his funerary monument at Abusir; his successors Menkauhor and Djedkare Isesi chose sites elsewhere,[47][96][97] and Abusir ceased to be the royal necropolis.[98][93] But the site was not abandoned. The Abusir Papyri demonstrate that funerary cults remained active at Abusir at least until the reign of Pepi II at the end of the Sixth Dynasty.[96] Priests who served Neferirkare include Kaemnefret, priest of Neferirkare's pyramid and sun temple and of Sahure's pyramid;[99] Nimaatptah, priest in the pyramid and sun temple of Neferirkare;[100] Kuyemsnewy and Kamesenu,[l] priests of the cults of Sahure, Neferirkare, and Nyuserre;[102][101] Nimaatsed, priest of the pyramids of Neferirkare, Neferefre, and Nyuserre;[103] Khabauptah, priest of Sahure, Neferirkare, Neferefre, and Nyuserre Ini.[104]

Verner believes that royal cultic activities ceased by the First Intermediate Period.[47] Málek notes that some limited evidence for the persistence of the cults of Neferirkare and Nyuserre throughout the Herakleopolitan Period exists, though this means Nyuserre's cult operated continuously until at least the Twelfth Dynasty.[105] Professor Antonio Morales believes funerary cults may have continued beyond the Old Kingdom,[106] in particular the cult of Nyuserre appears to have survived both in its official form and in popular public veneration until the early Middle Kingdom,[107] and some scant evidence in the form of two statues[m] dated to the Middle Kingdom may suggest that Neferirkare's cult was active during that period as well.[109]

The necropoleis near Memphis, specifically those at Saqqara and Abusir, were used extensively during the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty (c. 664–525 BC).[110] Considerable quantities of stone were required to build these tombs, and this was very probably sourced from the Old Kingdom pyramids, thereby inflicting further damage to them.[111] Graves estimated to be from the fifth century BC have been discovered in the vicinity of Neferirkare's mortuary temple. One yellow calcite gravestone, discovered by Borchardt, bears an Aramaic inscription: "(Belonging) to Nsnw, the daughter of Paḥnûm" alternatively read as "(Belonging) to Nesneu, the daughter of Tapakhnum".[112] A second inscription, found by Verner on a limestone block in the mortuary temple bears the inscription: "Mannu-ki-na'an son of Šewa". The dating of this second inscription is uncertain, but may plausibly be from the same period.[113]

- Mummified remains in a canvas cartonnage dated to the 26th Dynasty

- Aramaic inscription discovered by Ludwig Borchardt

Family cemetery

[edit]Pyramid of Khentkhaus II

[edit]

Borchardt initially thought a ruined structure on the southern side of Neferirkare's complex to be an unimportant mastaba, and surveyed it only briefly.[114] In the 1970s, Verner's Czech team identified it as the pyramid tomb of Neferirkare's consort, Khentkaus II.[114][115] Perring had previously discovered griffonage on a limestone block from the site of Neferirkare's tomb which mentioned "the King's wife Khentkawes".[115] She also appeared in a relief of the royal family on another limestone block on which Neferirkare's son, Neferefre, also appears.[115]

Khentkhaus's pyramid was built in two phases.[116] The first must have begun during Neferirkare's reign, as is evidenced by the inscription Perring discovered. The project was halted around the tenth year of Neferirkare's reign.[114] Verner suggested Neferirkare's untimely death interrupted the project and that it was finished during Nyuserre's reign.[114] The word "mother" appears inscribed above "wife" on another block indicating that the relationship between Khentkaus II and Nyuserre was as mother and son.[116][114] The completed structure has a square base measuring 25 m (82 ft; 48 cu) across each side, and with a slope of 52° would stand 17 m (56 ft; 32 cu) tall were it not in ruins. Her mortuary complex also includes a satellite pyramid, a courtyard, and an extended mortuary temple.[116]

Unfinished pyramid (Neferefre)

[edit]Located directly south-west[46] of Neferirkare's monument, and just to the west of Khentkaus II's, Neferefre's unfinished pyramid is another member of the family cemetery born around Neferirkare's tomb.[85] Built on the Abusir diagonal, Neferefre's pyramid was never completed owing to the unexpectedly early death of the pharaoh.[116][n] Originally built with a base length of 65 m (213 ft; 124 cu), slightly shorter than that of Sahure's pyramid, and with only a single step completed, the plan had to be altered to accommodate the remains of the king.[118] For this reason, the pyramid was hastily converted into a squared mastaba[75][117][119] and completed with the application of limestone facing at a slope of 78° and a clay and desert stone capping.[75] The accompanying mortuary temple is believed to have been built promptly following Neferefre's death.[75] The main features of the temple were a hypostyle hall, two large wooden boats, and a number of broken statues found in rooms near the aforementioned hall.[46]

Nyuserre's pyramid

[edit]

Nyuserre joined the family cemetery with his mortuary complex,[120] and was the last king to be interred in the Abusir necropolis.[98] Upon taking the throne, Nyuserre undertook to complete the three unfinished monuments of his closest family members: his father, Neferirkare; his mother, Khentkaus II; and his brother, Neferefre. The costs of this project burdened the construction of his own monument, which manifested itself in the siting of the complex.[120]

Instead of being seated on the Abusir-Heliopolis axis, Nyuserre's complex is nestled between Neferirkare's and Sahure's pyramids.[62][121][122] Respecting the axis would have meant placing the complex south-west of Neferefre's unfinished pyramid, and far from the Nile valley. The expense would have been unreasonable.[121]

The pyramid, located north-east of Neferirkare's pyramid,[21] stands around 52 m (171 ft; 99 cu) tall with a base length of about 79 m (259 ft; 151 cu).[92] The causeway connecting the valley temple to the mortuary complex was originally intended for Neferirkare's pyramid, but Nyuserre had these diverted, to serve his monument.[62][85]

Abusir papyri

[edit]

The monument's significance comes from the circumstances of its construction, and the contents of the Abusir papyri archives.[3][123][124] The Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal says that "this was the most important known collection of papyri from the Old Kingdom until the 1982 expedition of the Egyptological Institute of the University of Prague discovered an even richer cache in a storeroom of the nearby mortuary temple of Neferefre."[124]

The first fragments of the Abusir papyri were discovered by illicit diggers in 1893,[46] and sold and distributed around the world in the antiquities market.[125] Later, Borchardt discovered additional fragments while excavating in the same area.[126] The fragments were found to be written in hieratic; a cursive form of hieroglyphics.[75] Other papyri found in Neferirkare's tomb were comprehensively studied and published by the Egyptologist Paule Posener-Kriéger.[75][127]

The papyri records span the period between the reign of Djedkare Isesi through to the reign of Pepi II.[124] They recount all aspects of the management of the funerary cult of the king including the daily activities of priests, lists of offerings, letters, and inventory checks of the temple.[46][127][128] Importantly, the papyri connect the larger picture of the interplay between the mortuary temple, sun temple and other institutions.[127] For example, the fragmentary evidence of the papyri indicates that goods for Neferirkare's funerary cult were transported by ship to the pyramid complex of the king.[129] The full extent of the records of the papyri found at Abusir is unknown as more recent findings remain unpublished.[46]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Proposed dates for Neferirkare Kakai's reign: c. 2492–2482 BC,[2][7] c. 2477–2467 BC,[8] c. 2475–2455 BC,[9] c. 2446–2438 BC,[10] c. 2446–2426 BC,[11] c. 2373–2363 BC.[12]

- ^ Proposed dates for the Third Dynasty: c. 2700–2625 BC,[13] c. 2700–2600 BC,[14] c. 2687–2632 BC,[2] c. 2686–2613 BC,[9] c. 2680–2640 BC,[15] c. 2650–2575 BC,[11] c. 2649–2575 BC,[10] c. 2584–2520[16]

- ^ The term "true pyramid" refers to pyramids which have the geometric shape of a pyramid. That is, they have a square base with four triangular faces converging to a single point at the apex.[17]

- ^ Heliopolis, or Iunu, was a major city of ancient Egypt.[26] The temple of Heliopolis housed the sacred stone of Benben[27] – the primeval hill which arose from the primordial waters of Nu.[28] The temple was also the location of the cult of the sun god,[29] Atum.[30] The Egyptologist Mark Lehner proposes that the pyramids relation to the temple of Heliopolis is evidence in support of the pyramid being a sun symbol.[31]

- ^ Administrative centres in the early Old Kingdom period generally consisted of officials, personnel and some craftsmen. Memphis was the largest of these centres, and housed the royal court of the pharaoh during the Old Kingdom. The exact extent of the spatial organization of Memphis in the Old Kingdom remains unknown, though it was most probably not densely populated or walled like its contemporaries such as Sumerian cities. Most of the population of Egypt lived as peasant farmers in rural communities.[33]

- ^ transl. inbw-ḥḏ[34]

- ^ A solid central limestone core is constructed[42] and encased in successive layers of small stone blocks laid at an inwards slant.[42][43] As a result of the inwards tilt of each layer, the pyramid had a slope of about 74°.[42] These blocks were roughly dressed with the exception of the outer edge of each layer which was smoothed to flatten the surface.[43] This was the method of construction applied to Third Dynasty step pyramids.[42][43][44]

- ^ The purpose of the cult pyramid remains unclear, though, it may have had some relation to the pharaoh's Ka.[63]

- ^ The division of the Turin Canon into dynasties is a contested topic. The Egyptologist Jaromír Málek holds the conviction that the divisions in kinglists coincide with the transfer of the royal residence and believes that the introduction of dynasties, as used in modern study, began with Manetho.[69] Similarly, the Egyptologist Stephan Seidlmayer, considers the break in the Turin Canon at the end of the Eighth Dynasty to represent the relocation of the royal residence from Memphis to Herakleopolis.[70] The Egyptologist John Baines does not accept Málek's explanation for these features, and instead believes the list is divided into dynasties with totals given at the end of each, though only a few such divisions have survived.[71] Similarly, Professor John Van Seters views the breaks in the canon as divisions between dynasties, but in contrast, says that the criterion for these divisions remains unknown. He speculates that the pattern of dynasties may have been taken from the nine divine kings of the Greater and Lesser Enneads.[72] The Egyptologist Ian Shaw believes the Turin Canon gives some credibility to Manetho's division of dynasties, but considers the king lists to be a form of ancestor worship and not a historical record.[73]

- ^ It was originally believed that the pyramid was built by layering small rectangular stone blocks – which measured up to two feet (six-tenths of a metre) in length – and were angled inwards towards a solid core.[45] This theory was proposed initially by Richard Lepsius, an Egyptologist who visited the site briefly in the 1830s, and propagated by the archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, who conducted excavations in Egypt, including at Neferirkare's pyramid, at the start of the 20th century, after discovering what he believed were accretion layers on "internal faces" of the pyramids at Abusir.[45][74] It was challenged by Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi who conducted careful examinations of pyramidal architecture in the Old Kingdom and failed to find blocks lying on a slant in any Fourth or Fifth Dynasty pyramid they studied. Rather, they found that in each instance these blocks were always set horizontally. This lead them to reject the accretion layer hypothesis.[45] The theory was effectively disproven by the Czech excavation team at Abusir led by the Egyptologist Miroslav Verner.[45][74] The unfinished nature of Neferefre's monument allowed Verner's team to test Lepsius and Borchardt's hypothesis; if the pyramid had been constructed as suggested, then underneath the clay and desert stone capping, the pyramid's structure would have resembled the layers of an onion.[75] Instead the excavators found that the pyramid of Neferefre and pyramid of Neferirkare consisted of: an outer retaining wall of four or five courses of large horizontally layered stone blocks;[75] an inner pit of small horizontally layered roughly dressed limestone blocks;[76] with the gap between the two frames filled with a mash of crude limestone chunks, mortar and sand;[75][76] and not in the slanted fashion proposed by the accretion layer theory.[45][74][75]

- ^ transl. Bʒ–Kʒ–kʒi[93]

- ^ Kʒ-m-śn.w[101]

- ^ The statues are of a Sekhemet-hetep[ty] (transl. Sḫmt–ḥtp[ty]) from the Twelfth Dynasty. The first is notable for having the formula [n]r–pr ny–swt–bity Nfr–ir–kʒ–rˁ mʒˁ–ḫrw, meaning "of the temple of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Neferirkare, true of voice". The second statue was found at Abusir, providing corroborating evidence, but does not have a reference to the mortuary temple.[108]

- ^ The exact duration of Neferefre's reign remains undetermined, but the archaeological evidence and state of the unfinished pyramid suggest that his reign lasted no longer than at most three years, though most probably not more than two.[117]

References

[edit]- ^ Borchardt 1909, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Altenmüller 2001, p. 598.

- ^ a b c d Verner 2001e, p. 291.

- ^ a b c Verner 2001e, p. 463.

- ^ a b c d e f Arnold 2003, p. 160.

- ^ a b Bárta 2005, p. 180.

- ^ a b Verner 2001c, p. 589.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 30.

- ^ a b Shaw 2003, p. 482.

- ^ a b Allen et al. 1999, p. xx.

- ^ a b Lehner 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 288.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 389.

- ^ Arnold 2003, p. 265.

- ^ Verner 2001e, p. 473.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 287.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 87, 89.

- ^ Arnold 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Verner 2001b, p. 5.

- ^ a b Bárta 2017, p. 6.

- ^ a b Verner 2001b, p. 6.

- ^ Verner 2001e, p. 302.

- ^ Dodson 2016, p. 27.

- ^ Bárta 2015, Abusir in the Third Millennium BC.

- ^ Krejčí 2000, pp. 475–477.

- ^ Allen 2001, p. 88.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Verner 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Verner 2001e, p. 34.

- ^ Myśliwiec 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Isler 2001, p. 201.

- ^ Bard 2015, p. 138.

- ^ a b Jefferys 2001, p. 373.

- ^ a b c Bárta 2005, p. 178.

- ^ Bárta 2005, p. 179.

- ^ Krejčí 2000, p. 473.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Edwards 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 54.

- ^ Peck 2001, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d Lehner 1999, p. 778.

- ^ a b c Sampsell 2000, Vol 11, No. 3 the Ostracon.

- ^ Isler 2001, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f Sampsell 2000, Vol 11, No. 3 The Ostracon.

- ^ a b c d e f Edwards 1999, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e Verner 2001b, p. 7.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 105, 215–217.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 216.

- ^ Borchardt 1909, Titelblatt & Inhaltsverzeichnis.

- ^ Krejčí 2015, Térenní projekty: Abúsír.

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, p. 90.

- ^ a b Bárta 2005, p. 185.

- ^ Bárta 2005, pp. 183–185.

- ^ Bárta 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Bárta 2005, pp. 185–188.

- ^ Loprieno 1999, p. 41.

- ^ Allen et al. 1999, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Verner 2001e, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Lehner 2008, p. 144.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b c Lehner 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Verner 2001e, p. 296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Verner 1994, p. 77.

- ^ Verner 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Kahl 2001, p. 591.

- ^ a b Verner 2001e, p. 297.

- ^ Málek 2003, pp. 84, 103–104.

- ^ Seidlmayer 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Baines 2007, p. 198.

- ^ Seters 1997, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Shaw 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c Verner 2002, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lehner 2008, p. 147.

- ^ a b Verner 2014, Neferefre's (unfinished) pyramid.

- ^ a b c d e Verner 2014, Neferirkare's pyramid.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Verner 2002, p. 50.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e f Verner 2001e, p. 294.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Bareš 2000, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Verner 1994, p. 79.

- ^ a b Verner 2001e, pp. 294–295.

- ^ a b Verner 2001e, p. 295.

- ^ Allen et al. 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Altenmüller 2002, p. 270.

- ^ Verner 2001e, p. 318.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Lehner 2008, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Krejčí 2000, p. 483.

- ^ Lehner 2008, pp. 142, 144–145.

- ^ Edwards 1975, p. 186.

- ^ a b Goelet 1999, p. 87.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 79–80, 86.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, p. 86.

- ^ Mariette 1889, pp. 242–249, d. 23.

- ^ Mariette 1889, p. 250, d. 24.

- ^ a b Sethe 1933, p. 175.

- ^ Hayes 1990, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Mariette 1889, p. 329, d. 56.

- ^ Mariette 1889, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Málek 2000, pp. 245–246, 248.

- ^ Morales 2006, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 314.

- ^ Málek 2000, p. 249.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 313.

- ^ Dušek & Mynářová 2012, pp. 53, 65.

- ^ Bareš 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Dušek & Mynářová 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Dušek & Mynářová 2012, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Verner 2002, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Lehner 2008, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d Lehner 2008, p. 146.

- ^ a b Verner 2001a, p. 400.

- ^ Lehner 2008, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 138.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, p. 80.

- ^ Verner 2001e, p. 303.

- ^ Lehner 2008, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c Grimal 1992, p. 77.

- ^ Davies & Friedman 1998, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Strudwick 2005, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c Strudwick 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Allen et al. 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Krejčí 2000, p. 472.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; et al. (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623.

- Allen, James P. (2001). "Heliopolis". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2002). "Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom". In Coppens, Filip (ed.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001 (PDF). Vol. 70. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 269–290. ISSN 0044-8699.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86064-465-8.

- Baines, John (2007). Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815250-7.

- Bard, Kathryn (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- Bareš, Ladislav (2000). "The destruction of the monuments at the necropolis of Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2005). "Location of the Old Kingdom Pyramids in Egypt" (PDF). Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 15 (2). Cambridge: 177–191. doi:10.1017/s0959774305000090. S2CID 161629772. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-28.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2015). "Abusir in the Third Millennium BC". CEGU FF. Český egyptologický ústav. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1909). "Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Nefer-Ir-Ke-Re". Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Abusir. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Abusir; 5: Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft; 11 (in German). Leipzig: Hinrichs. doi:10.11588/diglit.30508.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Davies, William V.; Friedman, Renée F. (1998). Egypt Uncovered. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 978-1-55670-818-3.

- Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Royal Tombs of Ancient Egypt. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-2159-0.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Dušek, Jan; Mynářová, Jana (2012). "Phoenician and Aramaic Inscriptions from Abusir". In Botta, Alejandro (ed.). In the Shadow of Bezalel. Aramaic, Biblical, and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of Bezalel Porten. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 60. Leiden: Brill. pp. 53–69. ISBN 978-90-04-24083-4.

- Edwards, Iorwerth (1975). The pyramids of Egypt. Baltimore: Harmondsworth. ISBN 978-0-14-020168-0.

- Edwards, Iorwerth (1999). "Abusir". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Goelet, Ogden (1999). "Abu Ghurab/Abusir after the 5th Dynasty". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Hayes, William C. (1990) [1953]. The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 233920917.

- Isler, Martin (2001). Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- Jefferys, David (2001). "Memphis". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 373–376. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Kahl, Jochem (2001). "Old Kingdom: Third Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 591–593. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Krejčí, Jaromír (2000). "The origins and development of the royal necropolis at Abusir in the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 467–484. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Krejčí, Jaromír (2015). "Abúsír". CEGU FF (in Czech). Český egyptologický ústav. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Lehner, Mark (1999). "pyramids (Old Kingdom), construction of". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 778–786. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Loprieno, Antonio (1999). "Old Kingdom, overview". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 38–44. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Málek, Jaromír (2000). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Málek, Jaromír (2003). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Mariette, Auguste (1889). Maspero, Gaston (ed.). Les Mastabas de l'Ancien Empire: fragment du dernier ouvrage de Auguste Édouard Mariette. Paris: F. Vieweg. OCLC 10266163.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27 – July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Myśliwiec, Karol (2001). "Atum". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 158−160. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Peck, William H. (2001). "Lepsius, Karl Richard". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Sampsell, Bonnie (2000). "Pyramid Design and Construction – Part I: The Accretion Theory". The Ostracon. 11 (3). Denver.

- Seidlmayer, Stephen (2003). "The First Intermediate Period (c. 2160–2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 108–136. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Seters, John Van (1997). In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-013-2.

- Sethe, Kurt (1933). Urkunden des Alten Reiches (in German). Vol. 1. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung. OCLC 883262096.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Strudwick, Nigel (2005). Leprohon, Ronald (ed.). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13048-7.

- Verner, Miroslav (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. 69 (3). Prague: 363–418. ISSN 0044-8699.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Abusir". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001c). "Old Kingdom". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001d). "Pyramid". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–95. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001e). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). Abusir: Realm of Osiris. Cairo; New York: American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-723-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (2014). The Pyramids. New York: Atlantic Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78239-680-2.