Second Anglo-Mysore War

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Second Anglo-Mysore War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Mysore Wars and the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War | |||||||

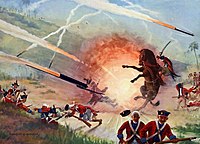

Depiction of action in the 1783 Siege of Cuddalore. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

The Second Anglo-Mysore War was a conflict between the Kingdom of Mysore and the British East India Company from 1780 to 1784. At the time, Mysore was a key French ally in India, and the conflict between Britain against the French and Dutch in the American Revolutionary War influenced Anglo-Mysorean hostilities in India. The great majority of soldiers on the company side were raised, trained, paid and commanded by the company, not the British government. However, the company's operations were also bolstered by Crown troops sent from Great Britain, and by troops from Hanover,[1] which was also ruled by Great Britain's King George III.

Following the British seizure of the French port of Mahé in 1779, Mysorean ruler Hyder Ali opened hostilities against the British in 1780, with significant success in early campaigns. As the war progressed, the British recovered some territorial losses. Both France and Britain sent troops and naval squadrons from Europe to assist in the war effort, which widened later in 1780 when Britain declared war on the Dutch Republic. In 1783 news of a preliminary peace between France and Great Britain reached India, resulting in the withdrawal of French support from the Mysorean war effort. The British consequently also sought to end the conflict, and the British government ordered the Company to secure peace with Mysore. This resulted in the 1784 Treaty of Mangalore, restoring the status quo ante bellum under terms that company officials, such as Warren Hastings, found extremely unfavourable.

Background

[edit]Hyder Ali ruled Mysore (though he did not have the title of king). Stung by what he considered a British breach of faith during an earlier war against the Marathas, Hyder Ali committed himself to a French alliance to seek revenge against the British. Upon the French declaration of war against Britain in 1778, aided by the popularity of ambassador Benjamin Franklin, the British East India Company resolved to drive the French out of India by taking the few enclaves of French possessions left on the subcontinent.[2] The company began by capturing Pondicherry and other French outposts in 1778. They then captured the French-controlled port at Mahé on the Malabar Coast in 1779. Mahé was of great strategic importance to Hyder, who received French-supplied arms and munitions through the port, and Hyder had not only told the British that it was under his protection, he had also provided troops for its defence. Hyder set about forming a confederacy against the British, which, in addition to the French, included the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad.

War

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

In July 1780, Hyder Ali invaded the Carnatic with an army of 80,000. He descended through the passes of the Eastern Ghats, burning villages as he went, before laying siege to British forts in northern Arcot. The British responded by sending a force of 5,000 to lift the sieges. From his camp at Arcot, Hyder Ali sent part of his army under the command of his eldest son, Tipu Sultan, to intercept a British force from Guntur, under the command of Colonel William Baillie, which had been sent to reinforce Colonel Hector Munro's army 233 kilometres (145 mi) to the north at Madras.[2] On the morning of 10 September 1780, Baillie's force came under heavy fire from Tipu's guns near Pollilur. Baillie formed his force into a long square formation and began to move slowly forward. However, Hyder Ali's cavalry broke through the formation's front, inflicting many casualties and forcing Baillie to surrender. Out of the British force of 3,820 men, 336 were killed. The defeat was considered to be the East India Company's most crushing loss in India up to that time. Munro reacted to the defeat by retreating to Madras, abandoning his baggage and dumping his cannons in the water tank at Kanchipuram, a small town some 50 kilometres (31 mi) south of Madras.[3] Naravane states in fact that it was a massacre with only 50 officers and 200 men taken prisoner, including Baille.[4]

Instead of following up the victory and pressing on for a decisive victory at Madras, Hyder Ali renewed the siege at Arcot, which he captured on 3 November. This decision gave the British time to shore up their defences in the south, and to despatch reinforcements under the command of Sir Eyre Coote to Madras.[3]

Coote, though repulsed at Chidambaram, defeated Hyder Ali in succession in the battles of Porto Novo[5] and Sholinghur, while Tipu was forced to raise the siege of Wandiwash, and besieged Vellore instead. The arrival of Lord Macartney as governor of Madras in the summer of 1781 included news of war with the Dutch Republic. Macartney ordered the seizure of Dutch outposts in India, and the British captured the main Dutch outpost at Negapatam after three weeks of siege in November 1781 against defenses that included 2,000 of Hyder Ali's men. This forced Hyder Ali to realize that he could never completely defeat a power that had command of the sea, since British naval support contributed to the victory.

Tipu also defeated Colonel Braithwaite at Annagudi near Tanjore on 18 February 1782.[4] This army consisted of 100 Europeans, 300 cavalry, 1400 sepoys and 10 field pieces. Tipu seized all the guns and took the entire detachment as prisoners. In December 1781, Tipu seized Chittur from British hands. These operations gave Tipu valuable military experience. Both Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan gained alliances with Ali Raja Bibi Junumabe II and the Mappila Muslim community and later met with Muslim Malay from Malacca under Dutch service.

During the summer of 1782, company officials in Bombay sent additional troops to Tellicherry, from whence they began operations against Mysorean holdings in the Malabar. Hyder Ali sent Tipu and a strong force to counter this threat, and the latter had pinned this force at Panianee when he learned of Hyder Ali's sudden death from cancer. Tipu's precipitate departure from the scene provided some relief to the British force, but Bombay officials had sent further reinforcements under General Richard Matthews to the Malabar in late December to relieve it before they learned of Hyder Ali's death. When they received this news, they immediately ordered Matthews to cross the Western Ghats and take Bednore. He felt compelled to do so despite a lack of sound military footing for the effort. He entered Bednore, which surrendered after Matthews drove Mysorean forces from the Ghats. However, Matthews had so overextended his supply lines that he was soon thereafter besieged in Bednore by Tipu, and forced to capitulate. Matthews and seventeen other officers were taken to Seringapatam, and from there to the remote hilltop prison of Gopal Drooge (Kabbaldurga) where they were seemingly forced to imbibe a lethal poison.[6]

On the east coast, an army led by General James Stuart marched from Madras to resupply besieged fortifications and to dispute Cuddalore, where French forces had arrived and joined with those of Mysore. Stuart besieged Cuddalore even though the forces were nearly equal in size. The French fleet of the Baillie de Suffren drove away the British fleet, and landed marines to assist in Cuddalore's defence. However, when word arrived of a preliminary peace between France and Britain, the siege was ended. General Stuart, who was engaged in disputes with Lord Macartney, was eventually recalled and sent back to England.

The British captured Mangalore in March 1783, but Tipu brought his main army, and after recapturing Bednore, besieged and eventually captured Mangalore. At the same time, troops from Stuart's army were joined with those of Colonel William Fullarton in the Tanjore region, where he captured the fortress at Palghautcherry in November, and then entered Coimbatore against little resistance.

- William Baillie Memorial, Seringapatam

- Plaque of the William Baillie Memorial, Seringapatam

- Memorial for the Battle of Porto Novo, 1781 at Porto Novo

Treaty of Mangalore

[edit]

During this time, company officials received orders from company headquarters in London to bring an end to the war, and entered negotiations with Tipu Sultan. Pursuant to a preliminary cease fire, Colonel Fullarton was ordered to abandon all of his recent conquests. However, due to allegations that Tipu violated terms of the cease fire at Mangalore, Fullarton remained at Palghautcherry. On 30 January the garrison of Mangalore surrendered to Tipu Sultan.

The war was ended on 11 March 1784 with the signing of the Treaty of Mangalore,[4] in which both sides agreed to restore the others' lands to the status quo ante bellum. The treaty is an important document in the history of India, because it was the last occasion when an Indian power dictated terms to the company.[citation needed]

Consequences

[edit]It was the second of four Anglo-Mysore Wars, which ultimately ended with British control over most of southern India. Pursuant to the terms of the Treaty of Mangalore, the British did not participate in the conflict between Mysore and its neighbours, the Maratha Empire and the Nizam of Hyderabad, that began in 1785. In Parliament, the Pitt administration passed Pitt's India Act that gave the government control of the East India Company in political matters.[7]

Battle honour

[edit]A battle honour, Carnatic was awarded for two periods: 1780–1784, during the Second Anglo-Mysore War, when Hyder Ali threatened Madras; and 1790–1792, during the Third Anglo-Mysore War, up to the siege of Mysore. Originally awarded to three battalions of Bengal Native Infantry in 1829, it lapsed after their disbandment due to participation in the 1857 uprising. In 1889, it was awarded to twenty units of the Madras Presidency Army. The battle honour is considered repugnant, an official term of opprobrium used by the Government of India.[8]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tzoref-Ashkenazi, Chen (June 2010). "Hanoverians, Germans, and Europeans: Colonial Identity in Early British India". Central European History. 43 (2): 222. doi:10.1017/S0008938910000014. JSTOR 27856182. S2CID 145511813.

- ^ a b Barua (2005), p. 79.

- ^ a b Barua (2005), p. 80.

- ^ a b c Naravane, M. S. (2014). Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj. New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3.

- ^ Malleson, G. B. (George Bruce) (1914). The decisive battles of India : from 1746 to 1849 inclusive. London : Reeves & Turner. p. 254. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Willasey-Wilsey, Tim (Spring 2014). "Searching for Gopal Drooge and the Murder of Captain William Richardson". The Journal of the Families in British India Society (31): 16–15. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Philips, C. H. (December 1937). "The East India Company 'Interest' and the English Government, 1783–4". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 20: 83–101. doi:10.2307/3678594. JSTOR 3678594. S2CID 167958985.

- ^ Singh, Sarbans (1993). Battle Honours of the Indian Army, 1757–1971. New Delhi: Vision Books. p. 102. ISBN 81-7094-115-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Barua, Pradeep P. (2005). The State at War in South Asia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1. LCCN 2004021050.

- Dalrymple, William (2019). The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Hardcover). New York: Bloomsbury publishing. ISBN 978-1-63557-395-4.

- Kaliamurthy, G. (1987). Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780–84). Delhi: Mittal Publications. OCLC 20970833.

- Roy, Kaushik (2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-58767-9. LCCN 2010040940.

- Tzoref Ashkenazi, Chen (2019). "German soldiers in eighteenth century India". MIDA Archival Reflexicon. pp. 1–8.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 414.