Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian civil war

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

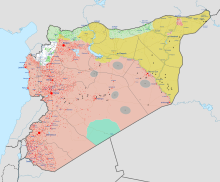

Ethno-religious composition of Syria immediately before the civil war in 2011[1]

The Syrian Civil War is an intensely sectarian war.[2] However, the initial phases of the uprising in 2011 featured a broad, cross-sectarian opposition to the rule of Bashar al-Assad, reflecting a collective desire for political reform and social justice, transcending ethnic and religious divisions.[3] Over time, the civil war has largely transformed into a conflict between ruling minority Alawite government and allied Shi'a governments such as Iran; pitted against the country's Sunni Muslim majority who are aligned with the Syrian opposition and its Turkish and Persian Gulf state backers. Sunni Muslims make up the majority of the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) and many hold high administrative positions, while Alawites and members of almost every minority have also been active on the rebel side.[4][5]

Despite this, Sunni recruits face systematic discrimination in the armed forces and ninety percentage of the officer corps are dominated by Alawite members vetted by the regime; based on their sectarian loyalty to Assad dynasty. SAA also pursues a truculent anti-religious policy within its ranks; marked by animosity towards Sunni religious expressions such as regular observance of salah (prayers), Hijab (headcoverings), abstinence from alcoholic drinks, etc.[6][7] The conflict has drawn in various ethno-religious minorities, including Armenians, Assyrians, Druze, Palestinians, Kurds, Yazidi, Mhallami, Arab Christians, Mandaeans, Turkmens and Greeks.[8][9]

In 2011, all the religious and ethnic communities, Muslim and non-Muslim, Arab, Turkmen or Kurd were united in their uprising against Assadist rule; disenchanted with the regime's corruption, authoritarian repression, nepotism, increasing poverty, unemployment, etc. This early unity highlighted the revolutionary subjectivity challenging the regime's attempts to sectarians the conflict, disputing the notion that the uprising was driven by sectarian reasons.[10] The peaceful movement, characterised by its anti-sectarian and pro-democracy stance, played a crucial role in articulating the non-sectarian grievances against the regime's authoritarian tactics.[11] Bashar al-Assad's strategy of importing Iran-backed Shia fundamentalists engaged in regional conflict with Sunni-majority countries and his portrayal as being the sole defender of Alawite interests from the Syrian Sunni majority; led to the transformation of the conflict into a sectarian war by late 2013.[12] Khomeinist militants have used its influence in regime-held areas to attempt Shi'ification through forced conversions, establishment of shrines, ethnic cleansing and demographic shifts by bringing in foreign Twelver Shia settlers from Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, etc.[13][14][15] Iranian government has been focusing its missionary efforts on converting Syria's Alawite minority to Twelver Shi'ism, by recruiting them in Iranian cultural and religious centres.[16]

Background

[edit]After early hopes that an era of political liberalization might follow Bashar al-Assad's succession of his father, these hopes flickered as Assad tightened his grip. He reined in Sunni Islamist opponents and sought to broaden his power base beyond minority sects. He promoted Sunnis to power and restored ties to Aleppo - a Sunni stronghold with which relations had been tense since the 1982 Hama massacre and the subsequent repression of the Muslim Brotherhood in the early 1980s.[17]

Assad adopted a more religious persona than his father, e.g. leaking videos of one of his sons reciting the Qur'an. While continuing to look to Iran for military supplies, he improved ties with Turkey. Yet Assad's policy of criticising jihadism in Iraq and Palestine carried risks and "enabled previously latent ethnic and sectarian tensions to surface, Sunni groups to organize, and unsettled other sects and power clusters who had prospered under his father" Hafez al-Assad.[17] Furthermore, the power and influence of Alawite elites in various sectors across the country; ranging from military, businesses, bureaucracy, etc. increased manifold times during the reign of Bashar al-Assad.[18] Additionally, Assad regularly stressed his Alawite roots in public appearances in order to suppress the rising number of dissidents from the traditionally loyalist Alawite base, who had begun playing prominent roles for the Syrian opposition.[12] This governance strategy showcased a mishandling of the diverse state-society dynamics, which, coupled with economic inequalities and political strains, resulted in escalated sectarian divisions. Approaching the moment of uprising, the regime's growing emphasis on sectarian identity in its public image further worsened the fragmentation of Syrian society.[19]

General issues

[edit]Both the opposition and government have accused each other of employing sectarian agitation. The opposition accused the government of agitating sectarianism.[20] Invoking minority sentiments and fears had long been a key policy of the Assads to ensure the regime's support amongst disenchanted Alawites.The regime dispatched the most loyal of the Alawite army units to fiercely crush the biggest protests.[21] Time Magazine reported that in Homs government workers were offered extra stipends of up to $500 per month to fan sectarian fears while posing as opposition supporters. This included placing graffiti with messages such as "The Christians to Beirut, the Alawites to the grave," and shouting such sectarian slogans at anti-government protests.[22] Some protesters reportedly chanted "Christians to Beirut; Alawites to the coffin".[23]

United Nations human rights investigators, concluded that Syrian civil war is rapidly devolving into an "overtly sectarian" and ethnic conflict, raising the specter of reprisal killings and prolonged violence that could last for years after the government falls. "In recent months, there has been a clear shift" in the nature of the conflict, with more fighters and civilians on both sides describing the civil war in ethnic or religious terms, "Feeling threatened and under attack, ethnic and religious minority groups have increasingly aligned themselves with parties to the conflict, deepening sectarian divides", said the report.[24]

The sharpest split arose between the ruling minority Alawite sect, a heterodox offshoot of Shi'ism constituting about 12% of total Syrian population, from which President Assad's most senior political elites, military officers, generals and associates are drawn; and the country's Sunni Muslim majority, mostly aligned with the opposition, the panel noted. This division was compounded by the regime's strategic mismanagement of ethnic relationships, which, instead of securing regime stability, led to an escalation in ethnic tensions and violence.[25] But the panel also said that the conflict had drawn in other minorities, including Armenian Christians, Assyrian Christians, Druze, Palestinians, Kurds, Yezidi and Turkmens.[8][26] Taking advantage of the existing social tensions; state media began trumpeting the sectarian card to discredit the protestors, in order to legitimise Assad's continuation and to gain critical support from those Alawites disillusioned with the regime.[27]

Nevertheless, there were some trends at this point that were not in line with a developing sectarian war. On 12 February 2013, a CNN report from inside Talkalakh revealed that the town itself was under rebel control, though government forces were only a matter of yards away, surrounding the town. Nevertheless, there was no fighting in or around the town thanks to a tenuous ceasefire between the warring sides brokered by a local sheikh and an Alawite member of parliament. Though isolated clashes have occurred, killing three rebels, and though government forces have been accused of harassing civilians since its implementation, the ceasefire has largely held. The town has returned to a degree of normal function, and some shops have started to re-open. Even the governor of Homs Province has been able to meet with rebels in the town, and has called the ceasefire an "experiment". Both sides reject sectarianism, stressing the need to keep foreign jihadist fighters out of the country. Nevertheless, the mainly Sunni rebels in the town stated that they remained committed to overthrowing Assad.[28]

International positions

[edit]In 2011, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated that the primarily Sunni protesters "have a lot of work to do internally" in order to gain the broad public support needed to form a genuinely national movement. She added, "It is not yet accepted by many groups within Syria that their life will be better without Assad than with Assad. There are a lot of minority groups that are very concerned." Clinton urged all opposition factions to extend further towards the minorities and to sustain their "moral high ground".[29] While Syrian opposition supporters are predominantly Sunni, it also include many Christian and Alawite figures in its ranks.[30]

Turkey Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been trying to "cultivate a favorable relationship with whatever government would take the place of Assad" regardless of the group.[31] In December 2012, US president Barack Obama praised the Syrian opposition as a pluralistic, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural popular movement, stating:

"the Syrian opposition coalition is now inclusive enough, is reflective and representative enough of the Syrian population that we consider them the legitimate representative of the Syrian people in opposition to the Assad regime"[32][33]

On the other hand, Russia has maintained a strategic alliance with the Assad regime, leveraging its influence to significantly bolster the Syrian government's position both militarily and diplomatically.[34] Its alignment includes substantial military support and diplomatic backing in international forums, notably at the United Nations, where Russia has used its veto power to block resolutions that could pressure Assad to make concessions or step down.[35][36][37] This unwavering support is a major source of frustration for the Syrian opposition, who view Russia’s stance as a significant obstacle to their goals. Viewing its involvement as a countermeasure to Western influence in the Middle East, Russia aims to protect its geopolitical interests, including its naval facility in Tartus.[38] This support is crucial in providing Assad with the military and logistical aid needed to withstand international pressure and maintain control,[39] while also aiming to prevent a geopolitical vacuum that Western powers could exploit if Assad's regime were to collapse, thereby underscoring Russia’s intent to remain a decisive power in the region.[40]

Despite international support, the Syrian opposition struggles to unite diverse groups[41][42] and articulate clear policies on key issues like the Baath Party and public sector reform, leading to skepticism among minorities like the Alawites about a stable post-Assad future.[43] This skepticism is fuelled by fears of potential chaos and sectarian backlash.[44] The opposition's disorganised approach and limited outreach to Alawites have inadvertently solidified Assad’s position as he portrays himself as the only option for maintaining Syria’s stability. This fragmented stance among opposition factions complicates their ability to govern effectively if Assad is ousted.[45]

History

[edit]In 2012 the first Christian Free Syrian Army unit formed,[46] yet it was reported that the Syrian government still had the support of the majority of the country's Christians of various ethnicities and denominations.[47][48] By 2013 an increasing number of Christians favored the opposition.[49] In 2014, the predominantly Christian Syriac Military Council formed an alliance with the FSA,[50] and other Syrian Christian militias such as the Sutoro had joined the Syrian opposition against the government.[51]

The Alawite sect of Islam has the second highest religious following in the Syrian Arab Republic and remains at the heart of the Syrian Government grassroot support; however, in April 2016 Alawite leaders released a document seeking to distance themselves from Shia Islam. The manifest titled "Declaration of an Alawite Identity Reform" stated that Alawism was a separate current "of and within Islam" and that the current political power (i.e. president Bashar al-Assad) did not represent the Alawite community.[52][53] Incidents of sectarianism amongst the Sunni population have been said to be rooted in that both Hafez al-Assad and Bashar al-Assad are Alawites, a minority fundamentalist Sunnis see as heretics. Additionally, the Syrian government maintains a network known as the shabiha, a shadow militia that anti-government activists allege are prepared to use force, violence, weapons and racketeering, whose members primarily consist of Alawites.[54][55] Iran provides training and equipping of Shia militants from Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan to fight with various sectarian Sunni militias in Syria,.[56] Minorities such as the Druze and Ismailis have refused to join these militias or be associated with the government,[57] with even some Alawites and Christians who are openly pro-government also refusing to join these militias or serve their conscription terms.[58]

Arab Sunnis

[edit]

Syrian Sunnis are subject to heavy discrimination from the Alawite dominated government apparatus; since the regime associates them with the Syrian opposition. As a result, Syria's Sunni community has suffered the vast majority of the brutalities and war crimes perpetrated by the Syrian Arab Army and pro-Assad Alawite militias during the Syrian Civil War.[59] Even though most of the opposition are composed of Sunnis, Ba'athist sympathisers of Arab Sunni background are present in pro-government forces as well.[60] The areas that have fallen under rebel control are mostly Sunni.[61] Shabiha have been reported of killing and perpetrating sectarian massacres of Sunnis, prompting kidnappings and alleged killing of Alawites by the Sunni side.[62][63] In addition, there have been numerous reports of sectarian violence against Sunnis by non-government Shiite Islamist groups, which have sought to justify their war-crimes by declaring that "We are performing our taklif [religious order]".[64] In one incident in late January 2012, Reuters reported that 14 members of a Sunni family were killed by the shabiha along with 16 other Sunnis in a formerly mixed neighbourhood of Homs that Alawites had purportedly fled four days prior.[65] Documented incidents of the regime's security forces targeting Sunni districts and villages date back virtually to the start of the uprising, including the shelling of Sunni neighbourhoods in Latakia by gunboats of the Syrian Navy in August 2011.[66] Abandoned Sunni homes have also been systematically plundered to the extent that "the country's newly flourishing flea markets took on a new name, "souk al sunna."[67]

The massacres in Houla and Qubeir, both Sunni farming settlements on the fault line between Sunni majority areas and the Alawite heartland of the Alawite Mountains, are said to be part of a plan intended by radical Alawite elements in the north-west to clear nearby Sunni villages in order to create a "rump state" that is easy to defend.[68] The Naame Shaam campaign has sought to highlight the sectarian nature of the Syrian government and the sectarian role of its main ally Iran, which includes attempts to alter the demographic composition of areas of Syria via the removal of Sunni inhabitants.[69] Some citizens loyal to the Ba'ath party coming from Sunni background continue to serve in the Syrian armed forces, despite massive Sunni desertions. Some Sunni citizens who are critical of the Assad regime do not support the opposition as well; due to the sufferings caused by widespread devastation as a result of the civil war. Hysteria over an alleged "Sunni triumphalism" in the scenario of an opposition victory has been a regular feature of Assad regime's propaganda since the eruption of the protests in 2011.[70][71]

The Times of Israel reported in June 2014 that various individuals interviewed in a "Sunni-dominated, middle-class neighborhood of central Damascus" claimed support for Assad among the Sunnis in Syria.[72] However, acknowledging the difficulty for establishing the true political opinion, the report states:

"It is difficult to ascertain the popularity or discontent with Assad inside Syria. The country has a pervasive security apparatus in place that punishes people for speaking out against the ruling establishment... Many who supported and respected him.. have turned against him because of the violence his government has inflicted on those who oppose him, including the relentless shelling of rural, opposition-held areas around Damascus."[72]

Describing reports of Hezbollah-led ethnic cleansing campaigns across Syria, US Chair of the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Ed Royce, stated in December 2015: "I’ve been briefed on the fact that [Iran is] even bringing in militias from Hezbollah and their families into Sunni dominated neighborhoods in Damascus and running their Sunni population out as they basically do an ethnic cleansing campaign".[74] SNHR reported in 2017 that the war has rendered around 39% of Syrian mosques unserviceable for worship. More than 13,500 mosques were destroyed in Syria between 2011-2017. Around 1,400 were dismantled by 2013, while 13,000 mosques got demolished between 2013-2017.[75]

Assadist security forces tend to view ordinary Sunni civilians with suspicion, accusing them as potential "fifth columnists" tied to the Free Syrian Army. At the same time, Syrian Arab Army has relied mostly on Sunni conscripts to fill its manpower; while the leadership at higher military positions was almost exclusively filled with Alawite loyalists of Assad. To prevent the overt perception of Alawite dominance, certain high ranking positions were awarded to non-Alawite supporters of the regime, while the deep state remained under the firm control of Alawite loyalists.[76] Sunnis also hold high governmental positions; the Prime Minister of Syria (previously Minister of Health) Wael Nader al-Halqi, the Minister of Defense and also Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Army and the Armed Forces (previously Special Forces) General Major Fahd Jassem al-Freij, Foreign Minister Walid Muallem and Major General Mohammad al-Shaar, an Interior Minister, are some of the Sunni Muslims in the positions of power. There also operate pro-Assad Sunni militias composed of Baathist loyalists, such as the Ba'ath Brigades. Brigades are made up of Sunni Syrians and other Arab Sunnis from the Middle Eastern region that adhere to pan-Arab ideals.[77] However, these militias were disbanded in 2018 to consolidate the regime's monopoly over armed forces.[78]

In 2018, The Economist reported that most of the Syrians forcibly displaced by the Ba'athist regime belong to the Sunni community as part of a systematic sectarian cleansing campaign to re-mold the demography in favour of the Assad dynasty. Hardline Assadists often justify the bombings in Sunni-majority regions by labelling the Sunni residents as "terrorists". Law No. 10 implemented by the regime has dispensed out thousands of homes and properties owned by displaced Sunnis to Iran-backed Khomeinist militants and pro-Assad loyalists.[79] Regarding the new religious policy adopted by the government towards its Sunni majority since outbreak of the civil war, The Economist article states:

“the country has been led by Alawites since 1966, but Sunnis held senior positions in government, the armed forces and business... The country’s chief mufti is a Sunni, but there are fewer Sunnis serving in top posts since the revolution. Last summer Mr Assad replaced the Sunni speaker of parliament with a Christian. In January he broke with tradition by appointing an Alawite, instead of a Sunni, as defence minister.”[79]

The controversial Law No. 10 passed by Bashar al-Assad in 2018 enabled the state to confiscate properties from displaced Syrians and refugees if they do not submit official documents within a timeframe of 1 year. The law is widely viewed as part of a social engineering campaign to remake Syria in the image of Bashar al-Assad, particularly by preventing the return of Sunni refugees. There are reports of regime plans to make Sunnis a minority within Syria in-order to consolidate its rule through the weaponization of Law no.10 and distributing vast swathes of confiscated properties to Assad loyalists and pro-Iranian militants.[a] Increasing sectarian violence has also resulted in Sunni holy places being attacked by Syrian and foreign Shia militias and the Syrian Army. Middle East Monitor reported in 2020 that graveyards of numerous Sunni figures have been demolished as revenge for the alleged destruction of Shia shrines.[84] In May 2020, eighth century Umayyad Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz's tomb in Idlib was destroyed by the Syrian Arab Army and Iranian-backed Shia militant groups.[84][85][86][87][88][89]

Alawites

[edit]

Alawites in Syria are a minority, accounting for less than 12 percent of the 23 million residents in Syria. Sunnis constitute the majority of the Syrian population. Journalist Nir Rosen, writing for Al Jazeera, reported that members of the Alawite sect are afraid of Sunni hegemony, as they were oppressed by Sunnis during Ottoman times and in the early years of the 20th century, the Sunni merchant class held much of the country's wealth and dominated politics.[90] Following Hafez al-Assad's coup, Alawites' position in Syria improved under the government of Assad, himself an Alawite, and they became the dominant elites in state bureaucracy and security apparatus.[91][92]

During the Syrian civil war, Alawites in Syria have been subject to a series of growing threats and attacks coming from Sunni Islamists.[93] In 2012, Adnan Al-Arour, a Syrian satellite television preacher based in Saudi Arabia, said that Alawites who supported Bashar al-Assad would be chopped up and fed to the dogs.[94][91]

Reuters investigated the mood and the condition of the Alawite community in early 2012. Several Alawites said that they have been threatened during the uprising for their religion and that they feared stating their names in cities where Sunnis are the majority. Some with distinguishable accents have tried to mask their speech patterns to avoid being identified as Alawites, Nir Rosen reported at around the same time, a phenomenon he suggested was not unique to Alawites in the increasingly sectarian conflict.[95] An Alawite originally from Rabia, near Homs, claimed that if an Alawite leaves his village, he is attacked and killed. Reuters reported that the uprising appeared to have reinforced support for President Bashar al-Assad and the government among ordinary Alawites, with a group of Alawites witnessed by its reporter chanting for Maher al-Assad to "finish off" the rebels. They were also convinced that if Assad fell, they would be killed or exiled, according to the investigation. Several claimed acts of sectarian violence had been committed against Alawites, including 39 villagers purportedly killed by Sunnis. Some also said that in cities like Homs, Alawites risked being killed or abducted if they ventured into Sunni neighbourhoods.[91] Many are fleeing their homes in fear of getting killed.[96]

The Globe and Mail reported that Alawites in Turkey were becoming increasingly interested in the conflict, with many expressing fears of a "river of blood" if Sunnis took over and massacred Alawites in neighbouring Syria, and rallying to the cause of Assad and their fellow Alawites, though the report said there was no evidence that Alawites in Turkey had taken up arms in the Syrian conflict.[97] A voice purported to belong to Mamoun al-Homsy, a former MP in Assad's parliament and one of the early opposition leaders, warned in a recorded message in December 2011 that Alawites should abandon Assad, or else "Syria will become the graveyard of the Alawites".[98] Jihadis in Syria follow the anti-Alawite fatwahs of the medieval scholar Ibn Taymiyah.[99] Simultaneously; anti-Sunni sectarianism arose drastically amongst Alawite loyalists of Bashar al-Assad over the course of the civil war.[100]

Studies of social dynamics of the conflict point out that anti-Sunni sectarian sentiments were discreetly cultivated in the Alawite community by the authorities so as to cultivate a mechanism of "social fear" amongst its members of other alternatives to the Ba'athist regime; so as to ensure their loyalty.[101] The rising sectarianism feared by the Alawite community has led to speculation of a re-creation of the Alawite State as a safe haven for Assad and should the leadership in Damascus finally fall. Latakia Governorate and Tartus Governorate both have Alawite majority population and historically made up the Alawite State that existed between 1920 and 1936. These areas have so far remained relatively peaceful during the Syrian civil war. The re-creation of an Alawite State and the breakup of Syria is however seen critically by most political analysts.[102][103][104][105] King Abdullah II of Jordan has called this scenario the "worst case" for the conflict, fearing a domino effect of fragmentation of the country along sectarian lines with consequences to the wider region.[106]

Most reports by Western media of sectarian violence against Alawites from the rebel side have related to fighters from Al-Qaeda's Syrian affiliate al-Nusra Front.[107] In September 2013, Al-Nusra fighters reportedly executed at least 16 Alawite civilians in the village of Maksar al-Hesan, east of Homs, including seven women, three men over the age of 65, and four children under the age of 16.[108] In October 2015, the head of al-Nusra, Abu Mohammad al-Julani, called for indiscriminate attacks on Alawite villages in Syria. He said "There is no choice but to escalate the battle and to target Alawite towns and villages in Latakia".[109]

Other Salafist preachers have echoed this sectarian rhetoric. Alawites were denounced by Egyptian Islamist cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi, based in Qatar.[110][111] According to Sam Heller, Muheisini, a Saudi Arabian Salafi cleric who served as a religious judge in the rebel Army of Conquest, issued fatwa to exterminate Alawite male combatants. While he was against killing Alawite women, he wrote that Alawite female fighters or captured Alawite women could potentially be executed as apostates.[112]

There have been allegations against the militias of the FSA (Free Syrian Army) as well. In December 2012, the massacres of Aqrab was initially attributed to pro-government militias but later alleged to have been perpetrated by rebels.[113][114][115] In June 2013, rebel fighters perpetrated the Hatla massacre of up to 60 Shia civilians. Video footage of the massacre showed rebels using sectarian language to describe the victims of the massacre.[116] In March 2013, Abu Sakkar, a commander of a rebel militia loosely affiliated with the FSA and later al-Nusra, was filmed cutting organs from the dead body of a Syrian soldier and saying: "I swear to God, you soldiers of Bashar, you dogs, we will eat from your hearts and livers! O heroes of Bab Amr, you slaughter the Alawites and take out their hearts to eat them!".[117] Abu Sakkar claimed the mutilation was revenge. He said he found a video on the soldier's cellphone in which the soldier sexually abuses a woman and her two daughters,[118] along with other videos showing Assad loyalists raping, torturing, dismembering and killing sunnis, including children.[119] (The incident was condemned by the FSA leadership, who declared they wanted him "dead or alive".[118]) In May 2013, an FSA spokesman said that Alawite settlements could be destroyed if the Sunni-majority town of Qusayr was seized by Assad loyalists, due to collateral damage from ongoing Battle of Qusayr. He added, "We don't want this to happen, but it will be a reality imposed on everyone".[120]

After the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War, the Alawites have suffered as a result of the community's perceived loyalty to the Assad government and attempts to monopolise regime control over the community. Many Alawites fear that a negative outcome for the government in the conflict could result in an existential threat to their community.[121][122]

Due to Assad regime's fear of mass-defections in military ranks, Alawite recruits are sent for active combat in the frontlines and forced conscriptions imposed by the Ba'athist state disproportionately targeted Alawite regions. This has resulted in a large number of 'Alawite casualties and Alawite villages in the coastal areas have suffered immensely a result of their support. Many Alawites, particularly the younger generation who believes that the Ba'athists have held their community hostage, have reacted with immense anger at Assad regime's corruption and hold the government responsible for the crisis. There has been rising demands across Alawite regions to end the conflict by achieving reconciliation with Syrian opposition and prevent their community from perceived as being associated with the Assad regime.[123][124]

In May 2013, SOHR stated that out of 94,000 killed during the war, at least 41,000 were Alawites.[125] By 2015, up to a third of the 250,000 Alawite male fighters of the Assad regime had been killed in the increasingly sectarian conflict.[121] In April 2017, a pro-opposition source reported Russian media assertions that 150,000 young Alawites had died.[126] Another report estimates that around 100,000 Alawite youths were killed in combat by 2020.[127]

Since 2020, numerous Alawite figures and activists have been more outspoken in their criticism of the Assad regime, with discontent related to rising corruption, arbitrary arrests, censorship and sectarian activities of Iranian-linked militant groups in regime-held areas. Ba'athist paramilitaries have regularly raided the houses and seized assets of Alawites accused of being disloyal. Alawite dissident journalists have fled Syria out of fear of being forcibly disappeared by the Mukhabarat.[128]

Alawites within the opposition

[edit]While there are Alawite activists opposed to Assad, Reuters describes them as isolated in 2012.[91] Fadwa Soliman is a Syrian actress of Alawite descent who is widely known for leading protests in Homs.[129] She has become one of the most recognized faces of the uprising.[130] Monzer Makhous, the representative of the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces in France, is an Alawi.[131]

In 2012, General Zubaida al-Meeki, an Alawite from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, became the first female military officer to defect to the opposition.[132] Influential Alawite intellectual and dissident Dr. Abdul Aziz al-Khair was imprisoned by the Assad government in October 2012. This incident led to widespread outrage within the Alawite community, which was denounced by hardline Assad loyalists. A mass-shooting between Alawite clans polarised over regime's policies occurred at Qardaha, in the same month.[133][134]

According to the Financial Times: "Opposition activists have worked hard to present a non-sectarian message. Video footage of protests in the Damascus suburbs shows protesters carrying posters with the crescent of Islam beside the Christian cross. Even exiled representatives of the [Muslim] Brotherhood, banned in Syria, have avoided sectarian discourse."[135] A group calling itself the Coalition of Free Alawite Youth offered an alternative for Alawites who do not want to take up arms. It invited them to flee to Turkey, promising that "within a few days, will secure free accommodation for them with a monthly salary that will shield them from humiliation."[136]

A new Alawite opposition movement, "Upcoming Syria", was founded on 21 November 2015.[137] Testimonies from Alawites in coastal regions state that Alawite families are sending their children abroad to avoid forced conscription by the Ba'athist government.[138] According to a 2020 report published by the Arab Reform Initiative:

"Many young Alawites are prioritizing their living conditions and believe that the regime is corrupt, responsible for all the successive crises that have been affecting Syrians, including youth, and incapable of finding solutions to any of them. However, it is hard to determine the prevalence of such discontent, due to their entrenched fear of the security apparatus."[139]

Christians

[edit]Christians in Syria, the majority of whom are Arab Christians, along with Assyrian and Armenian minorities, made up about 10% of the pre-war population of Syria and they are fully protected by Syria's 1973 constitution, which guarantees their religious freedom and allowed them to operate churches and schools.[140] However, the constitution stipulates that the President must be a Muslim.[141] Alongside Syria's Sunni community, Syrian Christians constitute the vast majority of Syrian refugees who got forcibly displaced during the civil war.[142] As a result of forced displacement and large-scale emigrations, recent reports estimate that Christian population has been reduced to around 300,000 members by 2022, less than 2% of the total population residing inside Syria.[143][144][145] Numerous human rights organizations have criticized the Assad regime for conducting sectarian practices against Christians.[146]

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, activists of Syria's Christian communities have been vigorous participants in revolutionary activities, ranging from peaceful pro-democracy demonstrations to armed resistance in Free Syrian militias. Some Christian opposition NGOs such as "Syrian Christians for Peace" are critical of armed activities against the Assad regime and instead champion only peaceful civilian mobilisation and anti-regime boycotts. Meanwhile prominent Christian activists have been heavily involved in the armed resistance, by joining various Local Co-ordination Committees, opposition militias and are active as representatives in various opposition bodies such as the Syrian National Council (SNC), Syrian National Revolutionary Coalition (SNRC), etc. George Sabra, former head of SNRC and current President of the SNC, is a member of the Christian community.[147][148][149][150]

On various occasions during the conflict, it has been reported that the Ba'athist government has been attempting to recruit supporters from the country's Christians. The Christians of Syria are members of various ethnicities and denominations.[47][48][151] In 2015, however, Syrian government recruiters were shot at while they were attempting to forcibly draft men in Christian areas, revealing their growing resentment with Ba'athist regime's militarization of the conflict.[152] Christian community has strongly resisted the forced recruitment drive of Syrian military in their neighborhoods, fearing that the regime wants to relinquish them as cannon-fodder for its own ambitions. As a result, many Christians have formed local militias independent of the regime.[153]

Despite strong resistance from Christian community, Ba'athist government has imposed discriminatory practices upon Christians through its forced conscription laws. These laws enable government authorities to seize all assets and properties of Syrian families accused of draft evasion. State policies primarily target members of Syria's Sunni and Christian communities, whose families are overwhelmingly opposed to fight fellow Syrians on behalf of the Assad regime. Many Christian families have been fleeing from regime-held areas to evade forced conscription.[154] Many rural and young Christians view emigration outside Syria, particularly EU countries as a way to advance career opportunities in education and employment, in addition to providing better prospects for their families.[155]

Christian activists have condemned Assad regime for launching sectarian attacks across Syria by deploying Syrian military forces and Alawite paramilitaries, which affect Christian communities because most Christians live in mixed Sunni-Christian neighborhoods. Many Christian organizations have criticized the Arab Socialist Ba'ath party of attempting to take their community hostage solely for propaganda purposes.[156][157] According to Samir, a Christian university professor in Aleppo:

"We are not just threatened by terrorist groups, we also have to suffer the Syrian regime's injustices like our Muslim brothers. We would like to live in a state that respects freedom and justice"[158]

In 2012, CBS News reported that some Christians support the Syrian government because they believe that their survival is linked to the survival of Syria's largely secular government.[159] An Al-Ahram article reported that the officials of numerous Syrian churches supported the government to extent of turning in members of the opposition within their own churches. Michel Kilo, a prominent Christian in the opposition, blasted these churches and called for Syrian Christians to "boycott the church until it is restored to the people and becomes the church of God and not that of the government intelligence agencies."[160] The Economist reported that Syrian Christians are well represented in the leadership of the opposition and many of them have increasingly begun to sympathize with the opposition. Social relations between Sunni and Christian communities are friendly; with leaders and members of both communities jointly attending funerals for slain opposition fighters and civilians who were killed by Assad's security appartus, church-based groups ferrying medicine to rebels, and they are also represented in the SNC and local committees.[161] The sectarian animosities that have arisen in certain segments of the disillusioned opposition tend to be directed at Alawites rather than Christians. Despite Assad's government's demands for public support and loyalty from the Christian clergy, most Syrian bishops do not intend to "carry their flocks" in toeing the regime's line.[161]

Many Syrian Christians believe that the Islamist-dominated governments which have been formed since the Arab Spring have become less willing to recognize the equal rights of Christians.[162] Some fear that they will suffer the same consequences of persecution, ethnic cleansing and discrimination as the indigenous Assyrian (aka Chaldo-Assyrian) Christians of Iraq and Coptic Christians of Egypt if the government is overthrown.[163] Most protests have taken place after Muslim Friday prayer, and the Archbishop of the Syriac Orthodox Church in Aleppo told the Lebanon-based Daily Star, "To be honest, everybody's worried, we don't want what happened in Iraq to happen in Syria. We don't want the country to be divided. And we don't want Christians to leave Syria."[164]

According to International Christian Concern, Christians were attacked by anti-government protesters in mid-2011 because they did not participate in the protests.[165] Christians were present in early demonstrations in Homs, but the entire demonstration walked off when Islamist Salafi slogans were shouted.[166]

Nevertheless, members of Christian sects have not always responded to the war in a uniform manner. The Christian hamlet of Yakubiyah in northern Idlib Province was overrun by rebel forces in late January 2013. Government forces withdrew from Yakubiyah after brief fighting at a checkpoint on the outskirts of the village, sparing the village from destructive street fighting—not a single resident died in the takeover of the town. The population before the war was mixed between Armenian Apostolics and Eastern Catholics, but most Armenians had fled the village with the army, being widely suspected of collaboration. Only some Catholics remained, the group having widely refused to take up arms for the government in Yakubiyah. The two Armenian churches suffered damage as a result of the war. The garden of one had served to house armoured vehicles of the army units who had held the village, and soldiers had used its courtyard as a dump. After rebels took the town, the Armenian churches fell victim to looters, who stole nearly everything of value from them—but also left religious texts alone. The single Catholic church in the village, however, remained untouched. Those residents who had not fled the fighting reported amicable relations with the rebel units occupying the town.[167] However, relations between local Sunni rebels and the remaining Christian civilians in the town broke down catastrophically over the following months. Rebels came to suspect the Christians of harbouring pro-government loyalties, but may have also wanted to seize the property of Christian families. Beginning with the wealthier families, rebels began targeting Yakubiyah's Christians for persecution. In a November 2013 interview, a Christian from the village who fled to the Turkish town of Midyat said that after six Christians were beheaded and after at least 20 other Christians were kidnapped, Yakubiyah was now virtually empty of Christians. She also made it clear by stating that those responsible were not jihadists, stating: "Al-Nusra didn't come to our village; the people who came were from villages close by, and they were Free Syrian Army."[168]

In 2012, the first Christian Free Syrian Army unit formed,[46] yet it was reported that the Syrian government still had the reluctant support of the majority of the country's Christians of various ethnicities and denominations.[47][48] In 2014, the ethnic Syriac Orthodox Christian Syriac Military Council formed an alliance with the FSA,[169] and other Assyrian Christian militias such as the Sutoro had joined the Syrian opposition against the Syrian government in allegiance with the YPG-led Syrian Democratic Forces.[51]

Attacks on Christians and churches

[edit]Throughout the course of the conflict, Syrian Arab Armed Forces has been pursuing a military strategy of deliberately bombing churches. Various human rights organizations have also accused the Ba'athist government of targeting Christian civilians.[170] As of 2019, around 61% of churches damaged in the Syrian civil war were targeted by the government forces. Out of the 124 documented incidents of violence against Christian religious centres between 2011 and 2019; 75 attacks were perpetrated the forces loyal to the Assad regime and 33 by various factions of the opposition.[171][172][173]

Some sources inside the Syriac Orthodox Church reported in 2012 an "ongoing ethnic cleansing of Christians" is being carried out by the Free Syrian Army. In a communication received by Agenzia Fides, the sources claimed that over 90% of the Christians of Homs have been expelled by militant Islamists of the Farouq Brigades who went door to door, forcing Christians to flee without their belongings and confiscating their homes. Mgr. Giuseppe Nazzaro, the Vicar of Aleppo later clarified that these reports were unconfirmed.[174]

The Christian population of Homs had dropped from a pre-conflict total of 160,000 down to about 1,000 in early 2012, due to heavy clashes between Syrian Arab Army and the Free Syrian Army.[175] Jesuit sources in Homs said the reason for the exodus was not because of threats from insurgent groups, but rather over the Christians' fears over the situation and that they had left on their own initiative to escape the conflict between government forces and insurgents.[176] Other charitable organisations and some local Christian families reported to Fides that they were expelled from Homs because they were considered "close to the regime". Fides said that Islamist opposition groups not only targeted those who refused to join the demonstrations, but also other Christians who were in favour of the opposition.[177] According to the Catholic Near East Welfare Association, opposition forces had occupied some historical churches in the old city district of Homs, leading to the Saint Mary Church of the Holy Belt being damaged during clashes with the Syrian army, and opposition groups also vandalised icons inside some of the churches.[162]

Local sources told Fides that Christians in Qusayr, a town near Homs, were given an ultimatum in 2012 to leave by armed Sunni rebel groups.[178][better source needed] Christian refugees from Qusayr, a town with a Christian population of 10,000 before the war, also reported that their male relatives had been killed by rebels.[179] The Vicar Catholic Apostolic of Aleppo, Giuseppe Nazzaro, stated that such reports were unconfirmed but noted that intolerant Islamist and terrorist movements are becoming more visible. He recalled a car bomb which exploded near a Franciscan school in Aleppo narrowly missing children present there.[180][181][better source needed] These reports were also strongly denied by opposition groups who instead blamed the government forces for inflicting the damage and forced displacements. For its part, the Vatican's ambassador in Syria, Mario Zenari, denied that Christians were being discriminated, saying they shared the "same sorry fate as the rest of the Syrian people."[160]

In 2012, Robert Fisk and official Orthodox sources claimed that an attack on Christians in Saidnaya was perpetrated by the FSA.[182][183]

In a 2012 report by Al-Ahram, Abdel-Ahad Astifo, an opposition Syrian National Council member and director of the European branch of the Christian Assyrian Democratic Organisation, stated that "The regime's forces and death squads are bombing both churches and mosques in several Syrian cities, with the aim of blaming others and injecting sectarian discord into the country."[160] On 26 February 2012, Al-Arabiya reported that Christians in Syria were being persecuted by the government, though the majority of those claims were rejected by official Christian sources in Syria.[141] The Al Arabiya article claimed that the government was targeting churches for perceived support to the opposition.[141] In another incident, Al-Arabiya reported that government forces attacked and raided the historic Syriac Orthodox Saint Mary Church of the Holy Belt in Homs.[141] Official Syrian church sources maintained that it was the anti-government militias that used the church as a shield and later damaged its contents on purpose.[184][185] Al-Arabiya reports in 2012 stated that the Syrian government has been persecuting Christian community leaders by various means. In one instance, a Christian activist sympathetic to the opposition told the newspaper that one priest had been killed by the government's forces and then state-run TV blamed government opposition for his death.[141]

In 2012, British conservative politician Edward Leigh issued alarm over the collapse of Assad regime and its implications for Syrian Christians under a potential majoritarian rule.[186] Syrian Christian refugees frequently express fear of rebels. When the town of Ras al-Ayn was captured by the FSA and al-Nusra from the government and the Kurdish-led PYD in late 2012, the Assyrian International News Agency reported that much of the town's Assyrian Christian population fled almost overnight. One refugee stated "The so-called Free Syrian Army, or rebels, or whatever you choose to call them in the West, emptied the city of its Christians, and soon there won't be a single Christian in the whole country."[187]

On 23 April 2013, the Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox archbishops of Aleppo, Paul (Yazigi) and Yohanna Ibrahim, were reportedly kidnapped near Aleppo by an armed Chechen group.[188] The president of the Syrian National Council George Sabra also corraborated this, stating that the bishops were allegedly being held by a rebel group in the vicinity of Aleppo and "were in good health".[189] However, later reports have accused the Ba'athist regime of being behind their kidnapping, since they have been foricbly disappeared ever since. The kidnappings had occurred a week after Archbishop Yohanna Ibrahim's public statements criticizing Bashar al-Assad.[190][191] On 2 July 2013, the Vatican reported that Syriac Catholic priest Francois Murad was killed by rebel militia in Ghassaniyah on 23 June while taking refuge in a Franciscan convent.[192][193] On the other hand, various Christian Bishops have also strongly condemned the Assad government for its actions against Christian community.[194] Blaming Ba'athist regime's indiscriminate targeting of Syrian cities for triggering forced expulsions and large-scale migration of Christians outside of Syria, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop Yohanna Ibrahim stated:

"Christians are not targeted, nor are churches, but what happens is that they are subjected to indiscriminate attacks.. the situation in Syria differs from the situation in Iraq, and the survival of Christians in Syria is not linked to the survival of Bashar al-Assad's regime"[195][196]

Syrian Churches have been demolished by Turkistan Islamic Party in Syria fighters.[197] In Jisr al-Shughur, according to Jihadology.net, a Church's cross had a TIP flag placed on top of it after the end of the battle.[198][199][200][201] The Uzbek group Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad (Tavhid va Jihod katibasi) released a video featuring themselves and the TIP attacking and desecrating Christian Churches in Jisr al-Shughur.[202][203][204][205][206][207] Jabhat al Nusra and Turkistan Islamic Party fighters cleansed the rural area around Jisr al-Shughour of its Syrian Christian inhabitants and slit the throat of a Syrian Christian along with his wife accusing them of being Syrian government agents, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.[208] Al-Arabiya said that the area was Alawite.[209][210] In the area to Aleppo's southwest, the entry via Turkey of Uyghurs into Syria was reported by a Syrian Christian who said they have seized control of Al Bawabiya village.[when?][211]

In January 2016, Kurdish Asayish security forces said members of the pro-government National Defence Forces were behind two bomb blasts that killed nearly 20 people in a Christian section of the city of Qamishli.[212] Syrian Network of Human Rights stated in 2019:

"The Syrian regime has always invoked good slogans, but on the ground, it has done the opposite. While the regime claims that it has not committed any violations, and that it is keen on protecting the Syrian state and the rights of minorities, it has carried out qualitative operations in suppressing and terrorizing all those who sought political change and reform, regardless of religion or race, and of whether this causes the destruction of the heritage of Syria and the displacement of its minorities."[172]

Arab Christians

[edit]The Arab Christians are mainly located in western Syria in Valley of Christians who are mainly Greek Orthodox or Melkites (Greek Catholics). The largest Christian denominations in Syria are the Greek Orthodox church,[213] and the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, who are exclusively Arab Christians, followed by the Syriac Orthodox. The appellation "Greek" refers to the liturgy which they use, sometimes, it is used in reference to the ancestry and ethnicity of the members, but not all of the members are of Greek ancestry; in fact, the Arabic word which is used is "Rum", which means "Byzantines", or Eastern Romans. Generally, the term is used in reference to the Greek liturgy, and the Greek Orthodox denomination in Syria. Arabic is now its main liturgical language.

Assyrians

[edit]

The Assyrian people, mainly located in the Northeast of Syria (with the bulk of their population in neighbouring northern Iraq, and others in south east Turkey and north west Iran), are ethnically and linguistically distinct from the main group of Syrian Christians, in that unlike the latter, who are of Aramean heritage but largely now Arabic speaking, Assyrians are of ancient Assyrian/Mesopotamian heritage, retain Eastern Aramaic as a spoken tongue, and are often members of the Assyrian Church of the East or Chaldean Catholic Church, as well as the Syriac Orthodox Church.

Unlike other Christian groups, The Assyrian dominated Christian militias in Syria are primarily allied with anti government Kurdish forces, whose secular attitude and tolerance of the minority has allowed for them both to work well in fighting against ISIS/ISIL, the enemy of both peoples. Some are pro-secularist opposition, with one militia member stating "the [Assad] regime wants us to be puppets, deny our ethnicity and demand an Arab-only state".[214] However, other armed Assyrian groups in al-Hassakah such as Sootoro, ally themselves with the government,[215] and have clashed with Kurdish YPG forces whom they accuse of trying to steal Assyrian lands.[216]

Assyrian communities, towns and villages have been targeted by Islamist rebels, and Assyrians have taken up arms against such extremists as ISIS,[217] and Assyrians and their militias and political organizations are staunchly anti-government. The Assyrian Democratic Organization is a founding member of the Syrian National Council and it is also a member of the executive committee of the council.[218] The ADO, however, have only participated at peaceful demonstrations and have warned against a "surge in the national and sectarian extremism".[219][220]

On 15 August 2012, members of the Syriac nationalist Syriac Union Party stormed the Syrian embassy in Stockholm in protest of the Syrian government. A dozen of its members were later detained by Swedish police.[221] By October 2012, the Syrian Syriac National Council had been formed. In January 2013, a military wing, the Syrian Syriac Military council, was formed, based in Al-Hasakah Governorate, home to a large Assyrian Christian population.[222]

Many Assyrian Christians found refuge in the Tur Abdin region in southern Turkey as fighting reached north-eastern Syrian by spring 2013. Many of them reported to have fled after they were targeted by armed rebels.[223]

By January 2014, the Syriac Military Council affiliated to the PYD.[224]

Several fighters killed in clashes prompted by Assyrians' move to set up checkpoints in Qamishli in fear of ISIL.[225]

Armenians

[edit]Many diaspora Armenians, from both the Apostolic and Catholic churches, have fled the fighting in Syria, with 7,000[226] emigrating to Armenia and a further 5,000[227] to Lebanon by February 2013. However, most Armenians still express support for Bashar Al-Assad[228] and fear the fall of the government,[229] considering him as a protector for the Christians persecution by Muslim extremists.[230]

A controversy over the role of Turkey in the Syrian civil war also occurred due to the manner and means of which Al-Nusra Front sacked the city of Kessab, which was looked at as one of the most significant Armenian majority towns in Syria. News agencies and local residents of Kessab reported that the town's Armenian Catholic and Evangelical churches had been ruined and burnt by the Islamist groups, along with the Misakyan Cultural Centre.[231][232][233] Around 250 families from Kessab who had taken refuge in Latakia returned to their homes a day after the Syrian Army recaptured the town.[234][235]

Kurds

[edit]For decades, Kurds have been suffering heavy discrimination under Ba'athist rule and was deprived of linguistic, cultural and educational opportunities. Kurdish language was banned and Kurdish activists were persecuted by the state.[59] The Syrian Civil War created a lot of instability in the region, providing opportunities for Kurdish militias to take control of parts of northern and eastern Syria, where the situation for Kurds became better than under the regime controlled regions.[59] A result of this has been the creation of Kurdistana Rojava (West Kurdistan), an autonomous Kurdish zone within Syria.[236] In this region, an autonomous administration and self-governing institutions have been set up and led by Kurds, also known as the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria.[237] This new autonomous government, albeit fragile, has become an important aspect in Syrian geopolitics and for many Kurds.[236]

Kurds in Syria

[edit]Kurdistan, centered on the Zagros mountain range on the borders of present-day Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, is where the majority of the Kurds live.[236] Estimates are that there are around 30 million Kurds around the world, mainly dispersed in the Middle East.[236] Approximately 1 million live in Syria and are viewed as a minority by the ruling elite because they are "a group of people, differentiated from others in the same society by race, nationality, religion, or language, who both think of themselves as a differentiated group and are of thought by others as a differentiated group with negative connotations.”[236] Most Kurds live in the region of Rojava in Western Kurdistan, with Qamishli as the largest Kurdish city in Syria and considered as the de facto capital of Western Kurdistan.[238] Many of the Kurds living in Syria have a Turkish background because of their exodus from Turkey during the Kurdish uprisings in this country in 1925.[238] With this exodus from Turkey, Kurdish nationalist intellectuals arrived in Syria as well, bringing the idea of a "national Kurdish group" to the small population of Kurds already living in Syria.[239] Because of their Turkish origin, many Kurds in northern Syria were deprived of the right to vote when the French mandate began in 1920. Even so, Kurds in Syria have positioned themselves differently from region to region. Kurds in Afrin and Damascus supported the French, while the majority of the Kurdish tribes in the Jazirah and Jarabulus region cooperated with Turkish troops loyal to Mustafa Kemal.[240] This difference in loyalty showed the various attitudes of the Kurds towards the mandate. Where some tribes supported Turkish troops, some leading Kurdish families like al-Yusiv and Shamdin opposed Arab nationalism, which Kemal propagated, because it "threatened their ethnic and clan-based networks".[240] Even though a sense of a Kurdish national identity developed slowly during the French mandate, prominent leaders of the Syrian Kurds like the Bedir Khan brothers furthered the cause of Kurdish nationalism.[238]

Institutionalization of sectarian division under the French Mandate

[edit]When Syria fell under French colonial rule in 1920, the position of the Kurds in Syria changed. The French authorities used the strategy of divide and rule to control and govern rural and urban elites and ethnic and religious minorities.[239] Contrary to how the British ruled Iraq, the French mandate system did not seek support from the Sunni-Arab majority, but started defending non-Sunni minorities, under which the Kurds.[239] The French authority for instance allowed the activities of the Khobyun League and their pursuit in strengthening the Kurdish position into one national organization. Indeed, as Tejel describes it, the French mandate actually used sectarian division to be able to govern Syria.[239] For the Kurds, the foundation of the Xoybun League in 1927 meant an unison on the part of the Kurds in their fight against Turkey.[241] For the Kurds, Turkey formed a threat to Kurdish nationalism and their pursuit for independence. For the French, the alliance with the Kurds was politically used as well in their border disputes with Turkey.[239] Researchers like Tejel and Alsopp argue that the French mandate used the "Kurdish card" as a tool to keep opposing states at bay, while at the same time ensuring the loyalty of the Kurds in their colonial rule.[241][239] The Kurds and the early rise of Kurdish nationalism was therefore embedded in a country divided by sectarian lines.[239]

Oppression by the Ba'athist Syrian government

[edit]Several Syrian Kurdish political parties established after 1946 were crushed when Kurdish areas were Arabized by the Ba'athist Syrian state, beginning in the 1960s. After seizing power in a coup, Hafiz al-Assad transformed Syria into a one-party dictatorship in 1970 and implemented several Arab nationalist policies. Following Hafez al-Assad's promulgation of Decree 93, the Kurdish status was further reduced when the creation of an Arab Belt under the government of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath party in 1973 expelled Kurdish natives from their lands in north-eastern regions of Syria.

The Arab Belt program was an ethnic cleansing campaign launched by the Ba'athist Syrian government of Hafez al-Assad between 1973 and 1976.[242][243][244] By implementing its Arab Belt programme, the Syrian government sought to change the demographics of northern parts of the Al-Hasakah region by sending Arab settlers, and change its ethnic composition of the population in favor of Arabs to the detriment of other ethnic groups, particularly the Syrian Kurds.[245][246] By the end of the programme in 1976, Syrian government forcibly deported approximately 140,000 Kurds living in 332 villages and confiscated their lands around a 180-mile strip across the north-eastern boundary-regions of Syria with Turkey and Iraq. Tens of thousands of Arab settlers coming from Raqqa were then granted these lands to establish settlements by the Ba'athist government.[247][248]

By pursuing radical Arab nationalist policies, Ba'athists attempted to justify their oppression of the Syrian Kurds, unless they assimilated themselves to the Arab identity of Syria. The Kurdish people and Kurdish identity have been perceived as major threats by the Ba'athist Syrian state and until after the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011, little has been done to halt the state's discriminatory treatment of Kurds in Syria. Scholars argue that the discrimination is seen by the majority of the Kurds as a threat to their national and ethnic identity, providing the main reason for establishing Syrian Kurdish political parties.

Establishing an autonomous region

[edit]

Even though the PYD was struggling to maintain a loyal base of followers, the party quickly gained momentum when the ongoing conflict between the Syrian regime and the armed opposition increased.[238][240][249] Where initially the PYD did not get involved in the war, this changed when Assad withdrew his military forces from several towns in northern Syria.[240][241][249][250] Considering the PYD was the only Kurdish political organization with a military force, the PYD seized this opportunity to capture these now unarmed towns. The military wing of the PYD, the People's Protection Units (YPG) took nearly every town in northern Syria where a Kurdish majority lived in just two months.[249] By January 2014, three autonomous cantons were established in the northern part of Syria, Rojava. The PYD's strength in the Kurdish regions in Syria is because of this well-organized and well-trained military wing. The PYD has enough resources to recruit, train and commit potential sympathizers to the party and now has an estimated 10.000-20.000 armed members.[240]

The PYDs pragmatic policy

[edit]Where the PYD's pragmatism gave this Kurdish organization several opportunities to cooperate for its own gains, the party also received many accusations by Syrian Kurds for collaborating with the Assad regime and the PKK in exchange for power in northern Syria.[249] The PKK argues that they do see Assad as a dictator, but "if Assad doesn't attack Kurds we will not go to war.”[251] Although the PYD has denied these accusations, there have been several instances during the Syrian civil war where the party collaborated with its opponents, like the PKK and the Syrian regime. Despite the PKK supporting the Assad regime, the PYD did have ties with this armed group – considered by the United States, Turkey and the European Union as a terrorist group - and received training in guerrilla warfare. Furthermore, the PYD has worked together with Assad military forces to fight the Islamic State which both actors perceived as a greater security threat.[249] Although the PYD rhetorically opposes the Assad regime, the party has opted for a pragmatist policy towards Assad, which has, amongst other things, resulted in sharing power with the Syrian regime in two other Syrian northern towns: Qamishli and Hasakah. Indeed, according to several authors, precisely this pragmatic stance has led to the party's success and survival.[240][249]

Kurdification in Rojava

[edit]On 10 October 2015, the YPG together with Arab, Assyrian, Armenian and Turkmen militias set up the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). By early 2016, the PYD had driven the Islamic State out the Kurdish areas the PYD controlled and received the United States protection against the Islamic State and Turkey.[249] With this support, the PYD was able to increase their territory in northern Syria and take the city of Hasaka in 2015. With the tides turning in their favour, the PYD installed a radical 'Kurdification' policy as part of their “Rojava revolution”. This radical democratic movement is aimed to not only establish an independent state during the sectarian struggle, but also to homogenize the ethnically diverse Rojava by using political power.[249][252] With a ‘re-Kurdification’ of Arabized Kurds, the PYD hopes to strengthen their position in areas where the Arabs are in the majority.[250] In order to keep this territory under control, the PYD has to delegate power to local Arab chieftains in areas where the Kurds are in the minority. This “blurring of sectarian lines” can be a strategic gamble or an attempt to cooperate with the Arabs to keep Rojava.[250] Here, the PYD uses the sectarian conflict in Syria to preach Kurdish nationalism as a democratic confederalism, promoting secularism, socialism and equality. However, several researchers argue that their struggle for Kurdish nationalism is only a tool for power politics.[240][249][250]

Currently, the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS) embeds the autonomous administration led by the Kurds. DFNS is still part of the Syrian state, but is autonomous in the sense that it executes self-governance.[237] The Administrative Regions Act, which has been passed in August 2017, divides the Rojava into six cantons and three regions.[237] The DFNS recognises and accepts all ethnic groups living in the Kurdis-led regions and promotes coexistence between the different communities. DFSN states that: “Cultural, ethnic and religious groups and components shall have the right to name their self-administrations, preserve their cultures, and form their democratic organizations. No one or component shall have the right to impose their own beliefs on others by force”.[237] This democratic confederalism is the foundational doctrine of Rojava and is developed by Abdullah Öcalan, the founder of the PKK. In this concept, state power is decentralised by letting small, local councils govern. However, in this northern Kurdish border zone, encompassing a mix of different minorities, ‘Kurdification’ is still pursued by the SDF.[250] Furthermore, even though the DFNS claims it promotes local democracy, researchers argue that the power is very centralized, even authoritarian.[240][250] Some news sources call this ‘re-Kurdification’ as just another form of oppression and argue that the PYD uses education as a tool of indoctrinization of PKK-Öcalan ideology.[253][254] By closing down schools who reject to follow the PKK curriculum and using their authority to deliberately force Arab families to leave their home in Kurdish-controlled areas, the PYD is accused of "mirroring the practices of the Assad regime in areas it controls".[254][255]

Current situation

[edit]In 2017, the SDF controlled around 25% of Syria.[250] The hold on these territories by the SDF was firm until Turkey launched an offensive in October 2019. Turkey's operation was aimed to create a 'safe zone' in Syria in order to push back the YPG (which Turkey sees as a terrorist organization) and relocate Syrian refugees.[238][256] This offensive has resulted in significant territorial loss for the SDF, under which key cities like Tel Abyad and Ras Al-Ayn.[256] Even though the United States supported the Kurds to fight IS back in 2014, when Erdogan told President Trump Turkey would begin with its cross-border operation to secure the safe-zone, President Trump said that the US troops would not get involved in this conflict.[238] On October 13, 2019, the Turkish offensive began with air strikes and shelling, resulting in over 13.000 people to flee the area.[256] With Kurdish forces concentrating on defending itself against Turkey, hundreds of IS-fighters and people suspected to have links with IS escaped from the camps in this affected area in which they had been held.[257] Currently, north-eastern Syria is divided by SDF-controlled areas, the Syrian regime forces, opposition militia and Turkish forces.

Druze

[edit]The Syrian Druze are concentrated in the southern province of Suwayda (or Sweida) and have become progressively more opposed to the government during the civil war. Despite the presence of high-profile Druze figures such as Gen. Issam Zahreddine in the Syrian military, who was implicated in severe human rights abuses—including the heavy shelling of civilian areas and the killing of American journalist Marie Colvin during the siege of Homs[258]— the general climate within the Druze-majority governorate has been one of refusal to participate in the conflict.[259] Druze leaders making statements against the Syrian government, Druze religious leaders being jailed for not celebrating the reelection of Assad, and community members refusing to serve conscription terms in the Syrian Arab Army or join pro Syrian government forces.[260] Since 2018, Druze community has also been apprehensive of the growing presence of Hezbollah and other Iran-backed militant groups in the southern regions of Syria.[261]

The Druze have been particularly opposed to members of their community being forced into Syrian government military service, with violent demonstrations and kidnappings of Syrian government security forces to force the release young Druze men captured to be forced into army conscription,[262] and incidents of the community breaking Druze individuals out of the Syrian government prisons.[58] The small minority of the Druze population who reside in the Israeli occupied Golan Heights (< 3% of all Syrian Druze) have been divided in their attitudes. Many amongst them have supported the Syrian opposition, while some Druze expressed support to Assad government. Associated Press reported that support for the Assad government among the Druze in Golan had largely "eroded" by 2012.[263][264]

In early 2013, it was reported that Druze were increasingly joining and supporting the opposition[265] and had formed Druze-dominated battalions within the FSA.[265][266] In January 2013, "dozens of Druze fighters joined a rebel assault on a radar base [...] in Sweida province".[265] In February 2013, several dozen Druze religious leaders in Sweida called on Druze to desert the Syrian military and gave their blessing to the killing of "murderers" within the government.[266] Lebanese Druze politician Walid Jumblatt, leader of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP), has also urged Syrian Druze to join the opposition.[267][268] In 2012 it was reported that the majority of Druze villages in the northern Idlib Province were supporting the opposition but were not involved in fighting.[269]

In 2012, there were at least four car bombings in pro-government areas of Jaramana, a town near Damascus with a Druze and Christian majority.[265] The Syrian government claimed that these were sectarian attacks on Druze and Christians by Islamist rebels.[270][271] Opposition activists and some Druze politicians claimed that the government itself is carrying out the attacks (see false flag) to stoke sectarian tensions and push the Druze into conflict with the opposition.[265][272]

In 2013, Israel is reportedly increasingly reaching out to the Druze of the Golan Heights with the intention of potentially creating a reliable buffer proxy force in the event Syria collapses into sectarian strife and anarchy in the near future.[273][274][275][276]

In early 2015, a Druze delegation from the Sweida province which was seeking aid from the government due to increasing attacks by ISIL was accused of being unpatriotic and rebuffed, because it refuse to join the Syrian government's forces.[57] Druze have refused to join Hezbollah led militias sent by the Syrian government, as they would expect to be sent to fight Sunnis.[262]

A massacre of Druze at the hands of Al-Qaeda affiliate Al-Nusra Front took place in June 2015 in Idlib. Nusrah issued an apology after the incident. Foreign Policy noted that there is absolutely no reference to the Druze in Al-Nusra's "apology", since Al-Nusrah forced the Druze to renounce their religion, destroyed their shrines and now considers them Sunni.[277][278][279] Nusra and ISIL are both against the Druze, the difference being that Nusra is apparently satisfied with destroying Druze shrines and making them become Sunnis while ISIL wants to violently annihilate them like it did to Yazidis.[280] The Druze land was taken by Turkmen.[281]

After Jabal al-Arba'een was subjected to bombardment by the coalition, foreign fighters fled to Jabal al-Summaq. Homes of the Druze religious minority of Jabal al-Summaq's Kuku village were forcibly stolen and attacked by Turkistan Islamic Party Uyghurs and Uzbeks.[282] In September 2015, "Sheikhs of Dignity" Druze militia accused the Assad government of orchestrating two car-bomb attacks in Suweida, which resulted in the deaths of its leader, Wahid al-Balous, and 27 others. Druze organized large scale protests in Suweida which resulted in the deaths of six loyalists of the Assad regime.[283]

Druze community became fervently opposed to the Assad government over time and has been vocal about its opposition against increasing Iranian interference in Syria.[284] In August 2023, economic hardships intensified as the Assad regime doubled public sector salaries amid hyperinflation and removed gasoline subsidies,[285] sparking mass protests against Assad regime erupted in the Druze-majority city of Suweida,[286][287] which eventually spread to other regions of southern Syria.[288][289][290] Druze cleric Hikmat al-Hajiri, religious chief of Syrian Druze community, has declared war against "Iranian invasion of the country".[291] The renewed vigor in these protests signified a major political awakening among the Druze, echoing through the region as a call to resist not just the Syrian regime but also external influences perceived as threatening their autonomy.[292]

Until May 2024, the regime's response to the protests in Suwayda differed from its actions in other regions.[293] Instead of employing direct violence, the regime used tactics such as facilitating kidnappings and creating security disturbances through local intermediaries. They also targeted Druze individuals outside Suwayda, issued threats to remove protection for the region, permitted extremist groups like ISIS to infiltrate it, stoked tribal conflicts to sow discord internally, and falsely accused the Druze of treason and collaboration with Israel.[294]

Shias

[edit]Twelver Shias

[edit]In October 2012, various Iraqi religious sects join the conflict in Syria on both sides. Twelver Shiite militant groups from Iraq, in Babil Governorate and Diyala Governorate, traveled to Damascus from Tehran, or from the Shiite holy city of Najaf, Iraq, claiming that they wanted to protect Sayyidah Zaynab shrine, a Twelver Shiite shrine in Rif Dimashq.[295]

In December 2012, Syrian rebel forces burned the Shia 'Husseiniya' mosque in the northern town of Jisr al-Shughur, inciting fears that the salafist groups would wage an all out war against Syria's minority religions.[296][297][298]

On 25 May 2013, Nasrallah announced that Hezbollah is fighting in the Syrian Civil War against Islamic extremists and "pledged that his group will not allow Syrian rebels to control areas that border Lebanon".[299] In the televised address, he said, "If Syria falls in the hands of America, Israel and the takfiris, the people of our region will go into a dark period."[299]

Jaysh al-Islam released a video showing the execution of ISIS members and showed a Jaysh al-Islam Sharī'ah official named Shaykh Abu Abd ar-Rahman Ka'ka (الشيخ أبو عبد الرحمن كعكة) gave a speech condemning "those who want (ISIS) to achieve" (وما الذي يريدون أن يحققوه), as "of the Madhhab of the Khawarij" (إنه مذهب الخوارج), "madhhab of hypocrisy" (مذهب النفاق), "madhhab of Abdullah ibn Saba' the Jew, who are joined with those under the banner of the dogs of (hell) fire "( مذهب عبد الله بن سبأ اليهودي إنه الإنضمام تحت لواء كلاب أهل النار).[300]

Ismaili

[edit]Ismaili Shias are also found around Hama region (Masyaf and al-Qadmus) and in Salamiyah, and were early supporters of the uprising against the government.[57]

As of March 2015 opposition activists have accused the government of attempting to stoke sectarian tentions in eastern Hama and Salamiyah, the burial place of the Ismaili sect's founder Ismail bin Jaafar, with recruitment drives aimed at Ismailis for pro-government militias for the purpose of setting up checkpoints to harass, rob and kill Sunnis.[301] The Ismaili community has been known to be peaceful and aimed at not engaging in any form of sectarianism and avoiding national conflict, perhaps under the spiritual guidance of its cultured Imam abroad, his Highness the Aga Khan IV. An Ismaili delegation that traveled to Damascus seeking aid from increasing ISIS attacks were reportedly told by Assad: "You have 24,000 draft dodgers in Salamiyeh. Let them join", referring to the fact that Ismailis do not wish to be associated with government militias, and the NDF has stood accused of refusing to protect Ismaili villages and looting Ismaili victims of ISIS attacks.[57]

Sufis

[edit]Sufis Muslims who mostly live in Damascus and Aleppo and in Deir al-Zor. Due to the Syrian Civil War, many are split into pro-government, pro-opposition and neutral currents. Sheikh Mohamed Said Ramadan Al-Bouti, a well-known Sufi cleric who had close ties to the authorities, was killed in a bombing at the Iman Mosque in Damascus. He had strongly criticized protesters and demonstrators in his support for the government. The government and the opposition have accused each other of the assassination. His son appeared on Syrian television where he supported the governments version of the event.