Seymour Goes to Hollywood

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

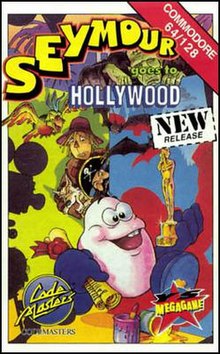

| Seymour Goes to Hollywood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Big Red Software |

| Publisher(s) | Codemasters |

| Composer(s) | Allister Brimble |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Amstrad CPC, Atari ST, Commodore 64, MS-DOS, ZX Spectrum |

| Release | (CPC and Spectrum) (Commodore 64) |

| Genre(s) | Platform, adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Seymour Goes to Hollywood, also known as Seymour at the Movies, is a platform and adventure game developed by Big Red Software and originally published in Europe by Codemasters in 1991. Players control Seymour, a small potato-like creature who wishes to be a film star. The film's script has been locked in a safe, meaning Seymour must solve puzzles by collecting and using objects scattered throughout the game in order to progress, ultimately retrieving the script and allowing filming to start.

The game was originally designed as part of the Dizzy series, with a working title of Movieland Dizzy, but the creators of Dizzy disagreed with the real-world direction the game had taken, despite it being 90% complete. The developers, Big Red Software, were given 12 weeks to create a new game with a different character. Seymour was adapted from Dizzy, with a new shape and fingers to differentiate the two.

Seymour Goes to Hollywood received both positive and average ratings from the video game press at the time, and was compared to Dizzy video games both positively and negatively. The character also received both praise and criticism for his shape.

Gameplay[edit]

Players guide Seymour through the game's locations, solving puzzles by collecting up to three objects at once and using them in pre-set locations.[4] Movement from one screen to the next is enabled through flip-screen, when Seymour touches the outer edge of one screen he is transported to the next.[5] The film studio where the game takes place features several rooms such as an office and eight film sets accessed from a maze of backlots, where each screen is only slightly different from the last. The doors to film sets are locked and Seymour must first locate the relevant key to gain access.[6] The sets' themes include films such as The Wizard of Oz and King Kong, as well as sets based on generic genres such as horror films and science fiction films.[7]

Characters throughout the film studios and movie sets will help Seymour on his quest with new objects and advice, but only if he helps them first.[8] Seymour's observations when collecting objects and sarcastic exchanges with other characters are communicated through speech bubbles.[6] One example of a puzzle is the Frankenstein's monster which must be created by combining body parts in a specific location on the horror film set. Once the monster is completed it smashes through one of the set's walls, allowing Seymour to access the set next door.[7]

Plot[edit]

Seymour has been given the starring role in a Hollywood film and duly arrives at the film studio to begin work. It transpires that the studio's boss, Dirk E. Findlemeyer the second, has taken a vacation to Miami. Findlemeyer has taken the key to his safe with him, which prevents filming from commencing because the safe contains the film scripts. Seymour must blow the safe with dynamite to access the scripts and then collect 16 Academy Awards from around the game and award one to each of the actors. Only then can filming commence.[7][9]

Development[edit]

Beginning with Magicland Dizzy, Codemasters sub-contracted Big Red Software, headed by Paul Ranson, to assist in the production of future Dizzy games in the series.[6][10] The success of Dizzy: Prince of the Yolkfolk prompted Big Red Software to take the series in a new direction.[10] The publisher decided that the titular egg character's next adventure should be set in a world based on real-life.[6]

Big Red Software started work and had 90% completed the project, which had the working title Movieland Dizzy, before the team was told to replace Dizzy with a new character. This was because the creators of Dizzy, the Oliver Twins, disagreed with the direction that Movieland Dizzy was taking the character, and after discussions Codemasters agreed.[6][10] Pete Ranson, Paul's brother, was one of Big Red Software's graphic designers and was given the job of creating a new character. This character began as a misshapen egg, was given fingers, and was given jump animations that lacked Dizzy's bounce. A friend of the Ranson's, having seen the character graphics, said that "he looked like a Seymour". The name "stuck" and the new character was completed.[6]

After making the decision to use a new character rather than Dizzy, Codemasters allowed Big Red Software free rein to develop the new game, only stipulating that it must be ready for release within 12 weeks. By this point Big Red Software was already familiar with platform adventure games.[6] The game retained the Dizzy graphic adventure title engine.[10] Pete Ranson had previously designed graphics for every Dizzy game bar the first, graphics were shared between Dizzy games and some were also recycled for Seymour Goes to Hollywood.[6]

After the Hollywood theme was decided on, the design team drew up a map and assigned objects and puzzles to different areas. The game was originally designed for the ZX Spectrum and then ported to the Amstrad CPC, due to the systems' similar architecture. However, the team struggled to port the game to the Commodore 64 due to it being a different machine altogether. The finished game is significantly changed from the incomplete Movieland Dizzy, which featured only film sets as locations, the surrounding film studio and backlots were not present.[6] The real-world studio elements were added after Dizzy was disassociated from the game.[10]

Reception[edit]

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Amstrad Action | 92%[9] |

| Crash | 85%[8] |

| Zzap!64 | 59%[11] |

| Amiga Format | 77%[12] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Amstrad Action | Mastergame[13] |

Both the Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum versions received high review scores,[14] one exception being the review in Sinclair User which was less positive.[15] The Commodore 64 version received a comparatively low score from Zzap!64. The magazine's reviewer wrote that despite the game featuring "brilliant humour and some of the best puzzles and animation seen in an arcade adventure",[11] it remained a "cruel parody" of the Spectrum version that "plays with all the style and grace of a drunken elephant!"[11] The Amiga version received both positive and average scores.[12] Seymour himself received a mixed response due to his appearance. Comments ranged from Seymour having "snatched Dizzy's crown"[9] to him being called "a peeled potato on legs",[15] an "albino mutant lardball"[12] and "a sort of slug-type thing".[16] David Crookes of Retro Gamer called Seymour a popular element and Big Red's most "infamous" character, but commented that Seymour did not match up to Dizzy.[10]

Seymour Goes to Hollywood was praised for its comparatively large size and for having more logical puzzles than Dizzy games, due to it being set in the real world.[16] Some players were critical of the size of the game and the time required to complete it.[6] The puzzles themselves were widely praised as "some of the best puzzles... ...ever seen in an arcade adventure",[11] and similar to Dizzy but with enough variation to "keep you scratching your head for hours".[17] Crash magazine's reviewer said that the puzzles may be too simple for players experienced with Dizzy games.[8] The game was compared to the Dizzy series by most reviewers, in both positive and negative lights. For instance, one reviewer opined that the game was indistinguishable from Dizzy games and succeeded for the same reasons,[18] while another reviewer called it average fare and asked "why didn't Codemasters just stuff it out as another Dizzy game?"[5] Crookes commented that though Seymour Goes to Hollywood borrows heavily from the Dizzy series it was a fulfilling game.[10]

Legacy[edit]

Five sequels were released in 1991 and 1992: Super Seymour Saves the Planet, Seymour: Take One!, Stuntman Seymour, Sergeant Seymour Robot Cop, and Wild West Seymour.[19][20]

References[edit]

- ^ "Seymour Goes to Hollywood for Amstrad CPC". GameFAQs. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Seymour Goes to Hollywood for Sinclair ZX81/Spectrum". GameFAQs. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Seymour Goes to Hollywood for Commodore 64". GameFAQs. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Davies, Jonathan (November 1992). "Game Reviews - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Amiga Power (19). Future Publishing: 99.

- ^ a b Merrett, Steve (August 1992). "VFM - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". CU Amiga. EMAP: 85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Retro - Behind the Scenes - Seymour Goes to Hollywood -Fat, Round but he didn't bounce along the ground... Seymour may have looked and played like Dizzy, but the gloves were off". GamesTM (97). Imagine Publishing: 136–139.

- ^ a b c Eddy, Richard (May 1991). "Previews - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Crash (88). Newsfield Publications Ltd: 23.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Nick (October 1991). "Review - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Crash (93). Newsfield Publications Ltd: 58, 59.

- ^ a b c Peters, Adam (June 1992). "Action Replay - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Amstrad Action (81). Future Publishing: 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g Crookes, David (2007). "Company Profile: Big Red Software". Retro Gamer (42). Imagine Publishing: 76–81.

- ^ a b c d Osborne, Ian (June 1992). "Flashback! - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Zzap!64 (85). Europress: 40, 41.

- ^ a b c Leach, James (September 1992). "Cheap 'n' cheerful - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Amiga Format (38). Future Publishing: 96.

- ^ Game review, Amstrad Action magazine, Future Publishing, issue 74, November 1991

- ^ Peters, Adam (November 1991). "Budget Bonanza - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Amstrad Action (74). Future Publishing: 48.

- ^ a b Sumpter, Garth (December 1991). "Budget Review - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Sinclair User (118). EMAP: 57.

- ^ a b Leach, James (December 1991). "Review - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Your Sinclair (72). Future Publishing: 41.

- ^ Roberts, Nick (March 1994). "Reviews - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". Amiga Force (16). Europress: 17, 18.

- ^ "Cheapos! - Seymour Goes to Hollywood". The One (47). EMAP: 88. August 1992.

- ^ "Super Seymour Saves the Planet". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Seymour - Take One!". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

External links[edit]

- Seymour Goes to Hollywood at SpectrumComputing.co.uk

- Seymour Goes to Hollywood at Lemon 64