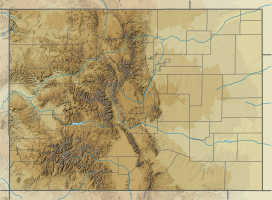

South Table Mountain (Colorado)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| South Table Mountain | |

|---|---|

View looking east from the top of Lookout Mountain | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 6,338 ft (1,932 m)[1][2] |

| Prominence | 475 ft (145 m)[2] |

| Isolation | 1.75 mi (2.82 km)[2] |

| Coordinates | 39°45′20″N 105°12′38″W / 39.7555429°N 105.2105438°W[3] |

| Geography | |

| Location | Jefferson County, Colorado, U.S.[3] |

| Parent range | Front Range foothills[2] |

| Topo map(s) | United States Geological Survey 7.5' topographic map Golden, Colorado[3] |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Mesa |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | February 14, 1859 by George Andrew Jackson, Thomas L. Golden and members of Chicago Company |

| Easiest route | South slope via Quaker Street |

South Table Mountain is a mesa on the eastern flank of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains of North America. Castle Rock, the 6,338-foot (1,932 m) summit of the mesa, is located on private property in Jefferson County, Colorado, 0.56 miles (0.9 km) directly east (bearing 90°) of downtown Golden.[1][2][3]

Mesa

[edit]The most distinctive feature of the mesa is its nearly flat cap that is formed by ancient Paleocene lava flows.[4] It is separated from companion North Table Mountain, which consists of the same geologic formation, by Clear Creek.

South Table Mountain is a popular scenic and recreational destination in the Denver metro area, and most of it is preserved as Jefferson County Open Space. Its landmark prominence is Castle Rock, a small higher butte that projects from the mesa's northwest end.

Geology

[edit]South Table Mountain is underlain by sedimentary rocks of the Denver Formation, which spans the interval from latest Cretaceous to early Paleocene time. An exposure of the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary layer has been identified and documented on its slopes.[5]

Two prominent, columnar jointed, cliff-forming lava flows form the nearly flat cap on South Table Mountain. The Ralston Dike, a body of intrusive monzonite located about 4 miles to the northwest, probably represents the volcanic vent from which the flows erupted.[6] The flows are about 62 to 64 million years old according to radiometric dating, which places them in the early Paleocene epoch. Generally referred to as basaltic, they are classified either as latite,[6] or as shoshonite.[7] They contain the minerals augite, plagioclase, and olivine altered to serpentine, with accessory sanidine, orthoclase, apatite, magnetite, and biotite.[7]

Zeolite

[edit]Both North and South Table Mountain are known for the wide variety of zeolite minerals [1] that occur in vesicles in the second flow. These include analcime, thomsonite, mesolite, chabazite, and others.[7] Excellent specimens of Table Mountain zeolites can be seen at the nearby Mines Museum of Earth Science.[8]

History

[edit]In times far past, South Table Mountain was ascended and used by American Indian tribes of the region, and archaeological remains are known to exist on its top. A piece of grape shot thought to be from either Spanish explorers or 1830s fur traders was found by Arthur Lakes on the mesa top in April 1895.[9] The earliest recorded ascent of the mesa was by Thomas L. Golden and other gold rushers while hunting during the Colorado Gold Rush on February 14, 1859. In 1906, father and son William H. and Clyde L. Ashworth built the original Castle Rock Resort, a cafe atop Castle Rock, where visitors were taken by burro up a trail on the north flank of Castle Rock. After vandalism destroyed it in 1907, the venture was abandoned until Charles F. Quaintance revived it in 1908 with a new cafe and burro train and a road from the south slope built by Harry Hartzell. This was supplemented in 1913 with a lighthouse, dance hall and funicular incline railway to the top. Business faded with the advent of the Denver Mountain Parks, and the funicular rails were salvaged for the allied effort in World War I in 1918. The idle resort was taken over by the Ku Klux Klan in 1923 as a major meeting and ceremonial place of its regional membership, during its rise to power in Colorado. This continued until the mid-1920s, after which it reverted to resort use as Lava Lane, and became idle again by 1926. The resort burned to the ground in an arson fire in 1927. During the 1910s-1920s, the city of Denver quarried gravel from the mountain's northeast alcove. In 1935, the Works Progress Administration built the Colorado Amphitheater for Camp George West on its southern side. Developers in 1957 originally wanted to build the Magic Mountain theme park at its northeastern alcove, until residents of Applewood protested and convinced them to build elsewhere. Subsequent attempts to develop or quarry the mountain including condominiums and a corporate headquarters continued through the remainder of the 20th century, and the mesa was gradually purchased or placed under easement by Jefferson County for open space. Today, much of South Table Mountain is open to the public, while southern portions are occupied by the Colorado State Patrol and National Renewable Energy Laboratory.[citation needed]

Feature names

[edit]

Although not necessarily recorded on United States Geological Survey maps, several historically named features are part of South Table Mountain:

- Castle Rock, originally known as Table Rock, a prominent butte at northwest end

- Slaughterhouse Gulch, a gulch upon its northern slope, likely named for farms once in the Coors Brewery valley

- Long Gulch, a lengthy gulch along Quaker Street on the south slope

- Crystal Springs, natural water springs in the vicinity of the head of Long Gulch

Wildlife

[edit]Animals known to frequent the mesa through time include rattlesnakes, coyotes, mountain sheep, cougars, deer, elk, and more. Of these, most except for the mountain sheep continue to live on the mountain today. The area, along with the adjacent north table mountain, is notorious among locals for its dense population of rattlesnakes, considered to be the most dangerous wildlife in the area.[10] Coyotes are frequently sighted in the area but tend to avoid humans. Cougars have been spotted by some hikers, but sightings are exceedingly rare.[11] The most commonly spotted wildlife tend to be elk, deer, coyotes, and a variety of birds.

Burial site

[edit]On August 4, 1911, Jonas "Mott" Johnson, Jr. discovered, according to the Golden Transcript, "a skull, a few bones and a few tattered remnants of clothing" washed down Long Gulch next to what is today Quaker Street on the south side of the mesa.[12] Tracing them to their source, the investigation found additional remains and clothing with conclusive evidence they belonged to an adult woman who had been murdered with remains buried at the gulch. Law enforcement investigators determined these to be the remains of Denver Italian matriarch Maria Laguardia, who was lured to the mesa and murdered for her gold by goddaughter Angeline Garramone on September 19, 1910.[13] Garramone was subsequently sentenced to life in prison. According to the Transcript, "Only a small part of the woman's body has been found" in 1911 and the possibility exists that further remains could still be at Long Gulch. Laguardia's remains that were found were given a proper burial at Mt. Olivet Cemetery.

Ascents

[edit]First ascent – earliest by a person of confirmed identity was on February 14, 1859, by gold discoverer George A. Jackson, partner Thomas L. Golden, and members of the Chicago Company, a gold seeking party, all of whom were hunting mountain sheep atop the mesa.

Fastest ascent – according to the Colorado Transcript issue of September 8, 1904, the fastest ascent was disputed between David G. Dargin, climbing to top of Castle Rock in 23:55 3/5 on November 6, 1859, and Charles Wade, climbing to top of Castle Rock from starting point of Washington Avenue Bridge at Clear Creek in 23:54 1/2 around February 1861. However, according to the website www.strava.com – onto which runners download GPS data of their activities – Golden resident Lex Williams ran from the Washington Avenue Bridge at Clear Creek to the summit of Castle Rock in 13:45 on October 31, 2018, making this the current Fastest Known Time (FKT). [2]

First automobile ascent – by Stanley Steamer, driven by George Hering on July 31, 1908, with 3 passengers (Charles F. Quaintance, John H. Reichert, and a Golden Transcript reporter) and camera equipment in 1908.[14]

Fastest automobile ascent – same as first automobile ascent, timed from starting point at 13th Street and Washington Avenue in 12 minutes 45 seconds, via South Golden Road and Quaker Street, proof of ascent published on front page of the Transcript showing automobile with passengers atop Castle Rock.

Helicopter ascent – first aerial ascent was by helicopter that flew onto Castle Rock in April 1948.[15]

See also

[edit]- List of Colorado mountain ranges

- List of Colorado mountain summits

- List of Colorado county high points

References

[edit]- ^ a b The elevation of South Table Mountain includes an adjustment of +0.967 m (+3.17 ft) from NGVD 29 to NAVD 88.

- ^ a b c d e "South Table Mountain, Colorado". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "South Table Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Drewes, Harald (2008). "Table Mountain shoshonite porphyry lava flows and their vents, Golden, Colorado" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5242, 28p.

- ^ Kauffman, E.G., Upchurch, G.R. Jr., and Nichols, D.J., 2005. The Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary at South Table Mountain near Golden, Colorado. In: Extinction Events in Earth History, Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences, vol. 30, p. 365-392.

- ^ a b Van Horn, R. 1957. Bedrock geology of the Golden Quadrangle, Colorado. U.S. Geological Survey, Map GQ-103.

- ^ a b c Kile D.E., 2004. Zeolites and associated minerals from the Table Mountains near Golden, Jefferson County, Colorado. Rocks and Minerals, vol. 79, no. 4, p. 218-238.

- ^ Bartos, P.J. 2004. Table Mountain zeolites: The Colorado School of Mines perspective. Rocks and Minerals, vol. 79, no. 4, p. 240-244.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". April 3, 1895 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ McKee, Spencer (2021-04-27). "Rattlesnake activity prompts warning about popular mountain in Colorado". OutThere Colorado. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ "ArcGIS Web Application". jeffcoparks.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". August 10, 1911 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "Says She is Not Guilty — The Middle Park Times November 10, 1911 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". August 6, 1908 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". April 22, 1948 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.