The Beyond (1981 film)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The Beyond | |

|---|---|

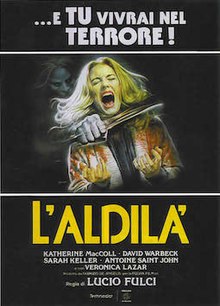

Italian theatrical release poster by Enzo Sciotti | |

| Italian | …E tu vivrai nel terrore! L'aldilà |

| Literally | And you will live in terror! The afterlife |

| Directed by | Lucio Fulci |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Dardano Sacchetti[1] |

| Produced by | Fabrizio De Angelis[1] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sergio Salvati[1] |

| Edited by | Vincenzo Tomassi[1] |

| Music by | Fabio Frizzi[1] |

Production company | Fulvia Film[1] |

| Distributed by | Medusa Distribuzione[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes[3] |

| Country | Italy[4] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $400,000[5] |

| Box office | £747.6 million ($416,652.16) |

The Beyond (Italian: …E tu vivrai nel terrore! L'aldilà, lit. "… And you will live in terror! The afterlife") is a 1981 English-language Italian Southern Gothic[6][7] supernatural horror film directed by Lucio Fulci. It is based on an original story created by Dardano Sacchetti, starring Catriona MacColl and David Warbeck. Its plot follows a woman who inherits a hotel in rural Louisiana that was once the site of a horrific murder, and which may be a gateway to hell. It is the second film in Fulci's Gates of Hell trilogy after City of the Living Dead (1980), and was followed by The House by the Cemetery (1981).[8]

Filmed on location in and around New Orleans in late 1980 with assistance from the Louisiana Film Commission, additional photography took place at De Paolis Studios in Rome. Released theatrically in Italy in the spring of 1981, The Beyond did not see a North American release until late 1983 through Aquarius Releasing, which released an edited version of the film titled 7 Doors of Death; this version featured an entirely different musical score and ran several minutes shorter than Fulci's original cut, and was branded a "video nasty" immediately upon its release in the United Kingdom. The original version of the film saw its first United States release in September 1998 through a distribution partnership between Rolling Thunder Pictures, Grindhouse Releasing, and Cowboy Booking International.

Following its release, reception of The Beyond was polarized. Contemporary and retrospective critics have praised the film for its surrealistic qualities, special effects, musical score and cinematography, but note its narrative inconsistencies; horror filmmakers and surrealists have interpreted these inconsistencies as intentionally disorienting, supplementing the atmospheric tone and direction. The Beyond is ranked among Fulci's most celebrated films, and has gained an international cult following over the ensuing decades.[9]

Plot

[edit]In 1927, artist and warlock Schweick works on a painting in Room 36 of the Seven Doors Hotel in New Orleans. He protects one of the seven gates of hell, which if opened will bring about the end of the world and the death of mankind. A lynch mob drags Schweick from his room and into to the hotel's basement, killing him for practicing black magic. Meanwhile, a white-eyed woman reads from the ancient tome "Eibon", prophesizing the opening of one of the seven gates.

Decades later, in 1981, Liza Merrill inherits the hotel and moves from New York City to refurbish and reopen it. A worker glimpses a white-eyed woman through a window and falls off his scaffolding. Local doctor John McCabe takes the injured man to hospital. The bell for Room 36 rings, but as the hotel has yet to open, Liza dismisses it as malfunctioning. A plumber named Joe investigates the lack of running water. In the flooded basement, he uncovers a bricked off area and accidentally opens the gate to hell. He is attacked by a ghoul, blinded and killed. The bodies of both Joe and Schweick are discovered by a maid, Martha, and are taken to the local morgue.

While driving into town, Liza encounters a blind woman named Emily and her guide dog, Dicky. Emily warns Liza that reopening the hotel would be a mistake and she should return to New York. At a bar, John urges Liza to give up on the hotel project. However, she refuses, thinking that it is her only remaining chance at financial success.

Later, Emily tells Liza about Schweick, warning her not to enter Room 36. Upon examining Schweick's painting, she states it was part of his seance, and his own death counted as a sacrifice to curse the land. After Liza scoffs at the warnings, Emily's hands begin to bleed, causing her to run with Dicky from the hotel in terror. Liza notices that neither of them made audible footsteps as they left. Despite Emily's warning, Liza enters Room 36 and discovers the Eibon as well as Schweick's corpse nailed to the bathroom wall. She returns to the room with John, but both the Eibon and the corpse are gone. Liza tells John about her encounter with Emily, but he insists there is no blind woman living in town. Furthermore, he says that the house where Liza claims Emily lives has been abandoned for years.

Liza's architect, Martin, visits the town library to inspect the hotel's blueprints, which reveal a large, unexplained space in the basement. Upon discovering this, he is knocked off his ladder by an unseen force, breaks his neck and is paralyzed. As he lies helpless on the floor, spiders eat him alive. Back at the hotel, Martha is cleaning the bathroom in Room 36 when Joe's corpse emerges from the bathtub water and kills her. John breaks into the old house where Emily is supposed to live. It is abandoned, but he finds the Eibon and begins to read it, learning that the hotel is apparently one of the seven gates to hell.

Emily is confronted in her home by the animated corpses of Schweick and the other recently deceased. She commands Dicky to attack. Although the dog chases away the undead, he next turns upon Emily, killing her. Meanwhile, Liza returns to the basement and is attacked by an undead worker. In her escape, she runs into John at the entrance. Upon investigating, there is no sign of the undead worker, and Liza begins to question her own sanity. The two drive to the hospital and find it deserted except for a Dr. Harris, Joe's daughter Jill, and a horde of the undead. Harris is killed by flying glass and John dispatches Jill when she transforms and attacks Liza.

John and Liza escape down a staircase but discover they have once again arrived in the basement. They proceed through the flooded labyrinth and stumble into a wasteland—the same landscape in Schweick's painting. No matter which direction they turn, they find themselves back at their starting point. They are ultimately blinded just like Emily and disappear.

Cast

[edit]- Catriona MacColl as Liza Merril (as Katherine MacColl)

- David Warbeck as Dr. John McCabe

- Cinzia Monreale as Emily (as Sarah Keller)

- Antoine Saint-John as Schweick

- Giovanni De Nava as Zombie Schweick[10]

- Veronica Lazăr as Martha

- Larry Ray as Larry (as Anthony Flees)

- Al Cliver as Dr. Harris

- Michele Mirabella as Martin Avery

- Gianpaolo Saccarola as Arthur

- Maria Pia Marsala as Jill

- Laura De Marchi as Mary-Anne

- Tonino Pulci as Joe the Plumber (uncredited)[11]

- Lucio Fulci as Librarian (uncredited)[11]

Pictorialist interpretations and themes

[edit]John Thonen of Cinefantastique wrote that The Beyond has "a story structure akin to that of an advanced fever dream".[12] Film scholar Wheeler Dixon similarly wrote that the "slight framing narrative is merely the excuse for Fulci to stage a series of macabre, distressing set pieces".[13] Writer Bill Gibron suggested that the film has a subtext of "slavery, witchcraft, mob justice—and perhaps the key to almost all Fulci narratives—revenge" at its core.[6]

The concept of "the beyond", which the characters Liza and John enter in the films' final sequence, is interpreted by film writer Meagan Navarro as a statement on "the Catholic concept of purgatory".[14] Fulci himself was a Catholic, and previous films of his dealt with aspects of his faith that troubled him, such as Don't Torture a Duckling (1972), which touched on corruption among clergy.[15]

A prominent theme, according to film scholar Phillip L. Simpson, is that of blindness as a result of exposure to evil, specifically tied to the Book of Eibon: "The book, like many other (in)famous 'evil' books found in literature and cinema, is a physical, written record of valuable occult knowledge that attempts to codify—accompanied by dire warnings that careless or ignorant deployment of that power will result in horrific consequences—what is otherwise usually represented as literally 'unseeable'."[16] Simpson interprets the film's "pervasive images of blindness and eye mutilation" as being directly consequential to characters' exposure to the book.[16] Simpson points out that only Schweick, the warlock lynched in the film's 1927 prologue, and Emily, a "seeress who transcends temporality", possess the "necessary sight" to interpret the contents of the book.[17]

Production

[edit]Development and pre-production

[edit]Producer Fabrizio De Angelis said that on his previous collaboration with Fulci, Zombi 2 (1979), they had aspired to make "a comic book movie… that is, instead of being scared, people would laugh when they saw these zombies".[18] Instead, audiences largely responded with fear, prompting them to make a straightforward horror film.[18] After making City of the Living Dead (1980), Fulci sought to make a follow-up film as part of a trilogy with the "Gates of Hell" being a unifying theme.[18] Simpson describes the trilogy as being loosely "connected by the trope of hapless mortals literally living on top of an entrance to Hell and then inadvertently falling into it".[19]

The hotel is an excuse, the characters are an excuse—what counted was the weaving of pure emotions.

– Dardano Sacchetti on the arbitrary nature of the film's setting[18]

The base concept for The Beyond was devised by Fulci, Giorgio Mariuzzo, and Dardano Sacchetti, with Sacchetti creating the film's original story.[18] A poster designed by Enzo Sciotti was produced based solely on the treatment in hopes of selling the film to international markets, and the film's title was chosen based on a conversation between Fulci and De Angelis.[18] De Angelis recalled Fulci discussing the film's concept with him: "So he's telling me this story about a couple moving into a house, where underneath is hell. And I was like, 'What does this mean?'… there weren't any dead people, maybe killed… No, there was hell under that house!" And he said 'the beyond.' And when I heard 'The Beyond,' that was already the title."[18] After receiving De Angelis's approval, Fulci requested that Sacchetti begin writing a full screenplay based on the brief treatment they had completed.[18] According to De Angelis, much of the plot was devised based on vague ideas Fulci had for various death scenes, as well as several key words that he felt unified his vision.[18] Some elements of the screenplay were derived in an arbitrary manner, such as the design of the Eibon symbol, which Fulci based on the shape of a trivial amateur tattoo his daughter had gotten on her arm.[18]

Sacchetti's conception of the "beyond" was based on his own ruminations on death, and the "suffering of being born condemned to death… [of being] born to be erased".[18] Sacchetti sought to depict the beyond as a hell full of dead souls, an otherworld existing "outside of Euclidean geometry".[18] Originally, the film's final sequence in which the characters enter the "beyond" was meant to take place at an amusement park, where the two main characters, now dead, are able to enjoy themselves in a "great amusement park of life".[18] Due to logistical restrictions, however, this was unable to be filmed, and the existing final sequence—in which the characters enter a vast desert landscape full of corpses—was devised by Sacchetti "on the spur of the moment".[18] In an interview, Fulci gave the film's budget as 580 million Italian lire, half the amount that De Angelis would declare it cost.[11]

Casting

[edit]Although Fulci originally intended to cast Zombi 2 star Tisa Farrow as Liza Merrill,[11] English actress Catriona MacColl was chosen after having worked with him previously on City of the Living Dead. She would go on to appear in the subsequent final film of Fulci's "Gates of Hell" trilogy, The House by the Cemetery, as well.[20] MacColl would later deem The Beyond to be her personal favorite film of the trilogy, stating that she remains drawn to the "decadent Italian macabre poetry" that she feels the film exudes.[21]

David Warbeck was cast as Dr. John McCabe after he and Fulci became friends during the making of The Black Cat (1981).[11] Originally, the roles of Joe and Professor Harris were to be played by Venantino Venantini and Ivan Rassimov, respectively, but they were replaced by two of Fulci's friends, stage actor Tonino Pulci and Zombi 2 co-star Al Cliver, whom the director affectionately nicknamed "Tufus".[11] Partway during the shoot, French actor Antoine Saint-John, who played the doomed painter Schweick, was replaced by Giovanni De Nava, who played the "zombified" version of the character;[11] De Nava is sometimes mistakenly credited for playing Joe.[18]

For the role of the ghostly Emily, Stefania Casini was originally considered, but Casini turned down the role as she did not want to wear the blinding contact lenses she would have been required to wear.[11] Fulci instead cast actress and model Cinzia Monreale, who had previously starred in his Spaghetti Western Silver Saddle (1978).[22] Monreale was drawn to the film as she felt Fulci's concept was "well written and full of mystery," and she had enjoyed her time working with him previously.[22]

Filming

[edit]The majority of The Beyond was filmed on location in late 1980 in New Orleans, Louisiana, as well as the outlying cities of Metairie, Monroe, and Madisonville. Larry Ray, a New Orleans resident and member of the Louisiana Film Commission, was hired to help Fulci scout locations.[23] While scouting, Fulci took a liking to Ray and hired him as a production manager and producer's assistant.[23] Within New Orleans proper, filming was completed in the Vieux Carré district, as well as on the campus of Dillard University.[24] The funeral sequence in the graveyard was shot at the Saint Louis Cemetery no. 1.[24]

The historic Otis House near Lake Pontchartrain, located within the Fairview-Riverside State Park, served as the Seven Doors Hotel.[25] During filming, the production designers aged the home's exteriors by spraying the siding with water and dark dye, as well as throwing cement and sand on the floors to make it appear dusty and dilapidated.[24] According to Ray, the sand damaged the original wood floors, and the production had to pay the State of Louisiana to restore them once filming wrapped.[24] The sequence in which Liza meets Emily on the bridge was shot on the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway,[24] while Emily's house was the same New Orleans residence used in Louis Malle's Pretty Baby (1978).[20]

To achieve the film's stark visual style, cinematographer Sergio Salvati photographed the New Orleans exteriors using "warm colors" in hope of capturing the "sun, the heat, [and] the jazz" of the city.[18] Salvati contrasted the urban New Orleans settings with the "cooler" interiors of the hotel, which often feature cool blue, orange, and violet lighting.[18]

According to Ray, Fulci had no official shooting script present while filming The Beyond,[23] only a treatment that ran three pages in length:[24]

The early concept script outline was only three pages with a story quite different from the one of the final movie. Fulci was always finding new ideas. Let me give you an example. 100 miles (160 km) from the Otis House that we used as the exterior of the Hotel of the story there was a long and narrow lake. We had been given the authorisation to shoot the exterior as well as interior of this historic house. Lucio Fulci or Sergio Salvati had the idea to use the lake for the scene with the boats loaded with the angry mob with torches. This produced beautiful reflections on the water and smoke machines provided the perfect atmosphere. In the end, lots of these scenes were dreamed up on the spot and added as a combined work between Fulci, David Pash and the crew.[24]

The majority of the cast were English speakers, while Fulci spoke Italian.[24] Due to the language barrier, much of Fulci's direction was done with "miming, making faces and moving his body in order to make the actors understand what he wanted of them."[24] As he was a fluent Italian speaker, Ray served as Fulci's translator and interpreter throughout the shoot.[23]

After filming had completed in the United States, additional photography took place at De Paolis Studios in Rome, primarily consisting of the special effects-intensive scenes. Among these were the interior shots of the film's opening sequence featuring the mob murder,[24] as well as interior replicas of Emily's home.[22] Some additional sequences featuring Emily's dog were also shot in Rome, which required the production to find a lookalike German Shepherd in Italy.[24] According to MacColl, the film's end sequence, in which she and Warbeck's characters enter "the beyond," was completed on their last day of shooting, on 22 December 1980.[20] The sequence was shot on an empty soundstage which had leftover sand from a previous film,[18] and random civilians were hired off the street to appear as inanimate corpses lying in the sand.[20] The sand was dampened with water, which, through evaporation, resulted in the natural fog effect present in the film.[18]

Special effects

[edit]

The special effects in The Beyond were achieved via practical methods,[26] and have been noted by scholars as Fulci's "signature violent set pieces."[27] The majority of the special effects-intensive scenes were filmed on sound stages in Italy.[26] Monreale recalled her time spent on set during the effects preparation as the most "intense," due to elaborate setups and hours spent properly achieving Fulci's desired visual outcome.[22] Among these for Monreale was her character's violent death sequence, in which she is viciously mauled by her dog.[22] To achieve the effect, the head of a fake dog was crafted, as well as a layered prosthetic neck which the dog tears open with its teeth.[22] This sequence alone took around three days to complete, with the dummy dog being manually puppeteered.[22] On set, Fulci jokingly referred to the fake dog head as "Puppola."[26]

The white contact lenses worn by several actors in the film were made of glass and hand-painted with multiple shades of white enamel.[26] They were described by both MacColl and Warbeck as being very uncomfortable; MacColl recalled that after completing the film's finale sequence, both she and Warbeck had difficulty removing them from their eyes.[20] The lenses also obscured the wearer's vision, rendering them completely or nearly-completely blind.[22] Monreale expressed that wearing the lenses was extremely difficult for her; all of her scenes except one required her to wear them, and she had to rely on the film's makeup artist, Maurizio Trani, for assistance navigating the sets.[22] To minimize discomfort, Trani would regularly remove the lenses from the actors' eyes and disinfect them between takes.[26]

One of the film's more elaborate special effects sequences was the death scene of Martin Avery, who is attacked by a horde of tarantula spiders.[26] According to Trani, crafting the sequence was "complicated," but "proved to be simpler than expected."[26] Special effects designer Giannetto DeRossi created half of a prosthetic mouth for the actor, Michele Mirabella, from latex and a dental cast he obtained from his dentist.[26] While some of the spiders were real, the ones filmed biting at Avery's mouth and face were fake, and controlled with handheld clamps.[26] Close-up shots of Mirabella's real mouth were intercut with ones of his false mouth (including close-ups of a fake tongue) as it is bitten by the spiders, resulting in a seamless image of the attack.[26]

The special effects during the film's first morgue scene in which a bottle of acid is poured over the face of Mary-Anne were created by effects artist Germano Natali.[26] To achieve the melting effect of the face, real sulfuric acid was dumped over a cast of the actress's face, which was made of a mixture of wax and clay; sulfuric acid dissolves the latter substance.[26] A similar dummy head was created to achieve the effect of the character of Joe's eyeball being gouged.[26]

The crucifixion of Schweick, shown in the opening sequence, was also achieved via practical methods: holes were cut for Saint-John to conceal his forearms behind the cross, while dummy forearms filled with fake blood reservoirs were attached to the front of the cross.[26] Two additional holes were cut at the ends of the dummy forearms, through which DeRossi inserted his own hands.[26] The result appears as two seamless arms, and allowed for the crucifixion to look authentic, as the hands were motile and could writhe in reaction.[26] Trani's hands appear onscreen as the nailer who completes the crucifixion.[26]

Music

[edit]Fulci commissioned composer Fabio Frizzi to complete a musical score for the film.[28] Commenting on writing the score, Frizzi said: "The distinctive aim of the film's soundtrack was to achieve an old goal of mine. I wanted to combine two different instrumental forms I had always loved: the band and the orchestra. When I started writing music some years before, I had learned to combine these two sounds; but for many reasons, the roles of strings and wind instruments were mainly created by keyboards. This time I decided to get serious."[28] The score features various instruments, including Mellotron and bass, as well as orchestral and choral arrangements.[28] Rolling Stone reviewers noted that as the film progresses toward its conclusion, "Frizzi's score also darkens, growing heavy, underlining the inescapable fate of the characters."[28]

In 2016, Rolling Stone ranked Frizzi's score the 11th-best horror film score of all time.[28] Chris Alexander of ComingSoon.net also ranked the film's main theme, "Voci Dal Nulla" (English: "Voices from the Void"), one of the greatest horror film themes ever composed.[29] In 1981, the score was released in Italy on vinyl through Beat Records Company.[30] On October 30, 2015, the independent record label Death Waltz issued the remastered score on vinyl.[31] A compact disc version had been released previously in 2001 by Dagored Records.[32] Grindhouse Releasing now includes the soundtrack with the Blu-ray release in the USA.

On October 17, 2019, Eibon Press announced that Grindhouse Releasing had discovered the original recordings of the score for the US 7 Doors of Death cut, and they had collaborated to release a limited-edition CD with a comic book adaptation of the film.[33]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Theatrical distribution

[edit]The Beyond was released theatrically in Italy on 29 April 1981,[34] where it grossed 747,615,662 lire on its initial run;[11] film historian Roberto Curti described this as "OK business", noting that while these takings were less than that of several of Fulci's earlier horror films, the film was widely distributed in other countries, and was especially successful in Spain.[35] In England, the film had difficulty with censors.[36] The BBFC passed it with an X rating demanding several cuts and subsequently it was considered a Video nasty.[36] It would not be released in the United Kingdom uncut until 2001 on home video.[36] In Germany, the film was released under the title Die Geisterstadt der Zombies (transl. The Ghost Town of Zombies).[37] The German theatrical version was the only version of the film in which the pre-credit sequence was printed in color; in the Italian and international versions, the sequence was printed in sepia.[38]

The Beyond did not see a U.S. release until 1983, when it was acquired for theatrical distribution by Terry Levine of Aquarius Releasing,[39] a New York City-based distributor who had previously handled regional distribution for John Carpenter's Halloween (1978).[40][41] Levine purchased the U.S. distribution rights for around $35,000,[41] and spent an additional $10,000 on additional post-production work, which included replacing Frizzi's music with a new score by Mitch and Ira Yuspeh,[8][42] as well as truncating it by several minutes to achieve an R-rating.[39] Aquarius released this alternate version of the film in the United States on 11 November 1983 under the title 7 Doors of Death.[43] According to Levine, the title change was a result of his belief that the original title was too nebulous, and that the film's "Seven Doors" plot device was a more interesting narrative hook that would intrigue audiences.[41] To promote this release, Levine screened the film for Kim Henkel and Tobe Hooper, the respective co-writer and director of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), who granted laudatory quotes about the film to be used in television and print advertisements.[41] Most of the cast and crew names for this version were also "anglicised" to appeal to U.S. audiences, with Fulci being credited as "Louis Fuller".[41] 7 Doors of Death was a commercial success, grossing $455,652 during its first week of release;[44] Levine estimated that the film turned him a profit of roughly $700,000.[41]

The uncut version of The Beyond was not made commercially available in the U.S. until after Fulci's death in 1996;[36] the North American distribution rights to the film were acquired by Bob Murawski and Sage Stallone for their company Grindhouse Releasing, which partnered with Quentin Tarantino and Jerry Martinez's Rolling Thunder Pictures and Noah Cowan's Cowboy Booking International to re-release the film through a series of midnight screenings that began in Los Angeles, New York City and five other locations on 12 June 1998, followed by a national roll-out. Remarking on Rolling Thunder's stake in the film, Cowboy Vice-president John Vanco noted that "Fulci is one of [Tarantino and Martinez's] favorite directors", and the pair "wanted to have someone with a little more kind of midnight movie specialized kind of background [to help distribute the film]".[45] By July 26, the re-release had made $123,843 at the box office.[46] Murawski's ownership of The Beyond's U.S. rights proved useful while editing Peter Parker's transformation scene in Sam Raimi's Spider-Man (2002): due to a lack of money to create original footage, he inserted a brief close-up shot of a spider from Martin's death scene into the sequence, along with footage from Raimi's Darkman (1990).[47] Grindhouse gave the film a second theatrical re-release in North America to celebrate its 24th anniversary, starting on 9 February 2015 at the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Yonkers, New York, and ending on 27 March 2015 in the Music Box Theatre in Chicago, Illinois.[48]

Critical response

[edit]Contemporaneous

[edit]People who blame The Beyond for its lack of story have not understood that it's a film of images, which must be received without any reflection. They say it is very difficult to interpret such a film, but it is very easy to interpret a film with threads: Any idiot can understand Molinaro's La Cage aux Folles, or even Carpenter's Escape From New York, while The Beyond or Argento's Inferno are absolute films.

– Lucio Fulci on The Beyond's reception[49]

Upon the film's 1983 release in the United States as 7 Doors of Death, critic Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times deemed the film visually "elegant," but noted: "as a thriller of the occult it's overly familiar, just another rotting-flesh ghoul parade."[50] Bill Kelley of the Sun-Sentinel similarly praised the film's visual elements, including the sepia prologue, but added: "The problem is, whenever someone in the film is trying to act, the camera is recording something that's really not worth seeing," ultimately classing it as a "Z-grade horror movie."[51]

The Akron Beacon Journal's Bill O'Connor criticized the plot for a lack of coherence, writing: "People get killed all over the hotel. Then, after they're killed, they get ugly.. We never know why they get killed or why they get ugly, which leads me to suspect that maybe this is an art film. At the end of the movie, the dead walk… Then the people leave the movie theater. They look just like the dead people who walked out of the morgue. Maybe this is not an art movie. Maybe this is a documentary."[52]

Tim Pulleine (The Monthly Film Bulletin) stated that the film allows for "two or three visually striking passages-and granting that, from Bava onwards, narrative concision has not been the strong suit for Italian horror movies—the film is still completely undone by its wildly disorganized plot."[4] The review also critiqued the dub, noting its "sheer ineptitude".[4]

Retrospective

[edit]Upon its 1998 re-release, critic Roger Ebert deemed it a film "filled with bad dialogue" and criticized it for having an incoherent plot.[53] In 2000, he included the film in a book of his "most-hated" movies.[53]

On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, The Beyond holds a 67% approval rating based on 21 critic reviews, with an average rating of 6.50/10.[54] AllMovie called the film a "surreal and bloody horror epic" and labeled it "Italian horror at its nightmarish extreme".[55] Time Out London, alternatively, called it "a shamelessly artless horror movie whose senseless story—a girl inherits a spooky, seedy hotel which just happens to have one of the seven doors of Hell in its cellar—is merely an excuse for a poorly connected series of sadistic tableaux of torture and gore."[56] Critic John Kenneth Muir wrote in Horror Films of 1980s: "Fulci's films may be dread-filled excursions into surrealism and dream imagery, but in the real world, they don't hang together, and The Beyond is Exhibit A."[57] A similar sentiment is echoed by Bill Gibron of PopMatters, who wrote of the film in 2007:

The Beyond is an incoherent, chaotic combination of Italian terror and monster movie grave robbing that is almost saved by its bleak, atmospheric ending. It is a wretched gore fest sprinkled with wonderfully evocative touches. It has more potential than dozens of past and present Hollywood horror films, yet finds ways to squander and squelch each and every golden gruesome opportunity. It's a movie that gets better with multiple viewings, familiarity lessening the startling goofiness of some of the dialogue and dubbing. It is a film that is far more effective in recollection than it is as an actual viewing experience. It would probably work best as a silent movie, stripped of the illogical scripting, stupendously redundant Goblin-in-training soundtrack drones, and obtuse aural cues.[58]

In the years since its release, The Beyond has acquired a cult following.[58] Time Out London conducted a poll with several authors, directors, actors and critics who have worked within the horror genre to vote for their top horror films. As of 1 October 2019[update], The Beyond placed at number 64 on their top 100 list.[59] Film critic Steven Jay Schneider ranked the film number 71 in his book 101 Horror Movies You Must See Before You Die (2009).[60]

Home video

[edit]On 10 October 2000, Grindhouse Releasing co-distributed the film in collaboration with Anchor Bay Entertainment on DVD in both a limited-edition tin-box set, and a standard DVD.[61] Both releases featured the fully uncut 89-minute version of the film.[62] There were only 20,000 limited-edition sets released for purchase. The limited-edition set was packaged in a tin box with alternative cover artwork, including an informative booklet on the film's production as well as various miniature poster replications.[61] The same year, Diamond Entertainment released a DVD edition bearing the 7 Doors of Death, which in spite of its usage of the US release title, is uncut at 89 minutes and sourced from the film's laserdisc.[63]

A Blu-ray version of the film was released in Australia on 20 November 2013.[64] Grindhouse Releasing, the film's North American distributor, released the film in 2015 on high-definition Blu-ray in the United States, featuring two Blu-ray discs as well as a CD soundtrack. The distributors also wanted to restore the 7 Doors version, but the original print of that version was assumed to be lost; trailers and TV spots for it, and an interview with Aquarius owner Terry Levene explaining the "Americanization" process, were included as special features instead. Levine also stated that he is content with the original version being praised and preserved, and admitted that he only made the 7 Doors version as a way to gain American interest.[65] As of 2018[update], a cut version of the film available for streaming via Amazon Video under the 7 Doors of Death title runs approximately 84 minutes.[66]

In 2020, Shameless Screen Entertainment released The Beyond on Blu-ray for the UK market, derived from a 2K scan of original elements, among which was the original color version of the film's prologue. Via seamless branching with the film or in a separate comparison video, four versions of the prologue are presented on the disc: the standard sepia version, the color version, a black and white version, and a variant of the color version featuring a digitally-created yellow tint, which is intended to replicate Salvati's original vision for the sequence ― that of "an old, yellowed photograph, something outside time, establishing a gap between the prologue and the present day as though they were two separate films, divided by an infinite arc of time indicating the Dimension of the Afterwards". Aside from two previously released audio commentaries — one with MacColl and Warbeck, and another with Salvati — the disc's special features include new interviews with Monreale, Mirabella, and Mariuzzo, and behind-the-scenes footage of Fulci from the filming of Demonia.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Howarth 2015, p. 219.

- ^ "…E tu vivrai nel terrore! L'aldilà (1981)". Archivo Cinema Italiano. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Muir 2012a, p. 351.

- ^ a b c Pulleine, Tim (1981). "…E tu vivrai nel terrore! L'Aldila (The Beyond)". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 48, no. 564. London: British Film Institute. p. 243.

- ^ Cait McMahon (26 October 2019). "Substream's 31 Days of Halloween: 'The Beyond' (1981)". Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b Gibron, Bill (19 May 2010). "More than Just Gore: The Macabre Moral Compass of Lucio Fulci". PopMatters. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Gibron, Bill (15 October 2007). "Lucio Fulci's The Beyond (1981)". PopMatters. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ a b Fonseca 2014, p. 105.

- ^ Biodrowski, Steve (20 February 2009). "Beyond, The (1981)- DVD Review". Cinfefantastique Online. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Curti 2019, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Curti 2019, p. 64.

- ^ Thonen, John (1998). "The Beyond: Resurrecting". Cinefantastique. Frederick S. Clarke. p. 120. ISSN 0145-6032.

- ^ Dixon 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Navarro, Meagan (24 February 2018). "Godfather of Gore Lucio Fulci's 'The Beyond'". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ O'Brien 2011, p. 257.

- ^ a b Simpson 2018, p. 245.

- ^ Simpson 2018, p. 249.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Salvati, Sergio; Sacchetti, Dardano; De Angelis, Fabrizio; Fulci, Antonella; et al. (2015). "Looking Back: The Making of The Beyond". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 2. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ Simpson 2018, pp. 246–247.

- ^ a b c d e MacColl, Catriona (2015). "Beyond and Back: Memories of Lucio Fulci". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 2. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ MacColl, Catriona; et al. (2015). "Introduction by Catriona MacColl". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 1. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Monreale, Cinzia (2015). "See Emily Play". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 2. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ a b c d Ray, Larry (2015). "The New Orleans Connection". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 2. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Grenier, Lionel (3 November 2012). "Larry Ray – actor/assistant to the producer (The Beyond)". LucioFulci.fr. Translated by Stefan Rousseau. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Ray, Larry (2014). "My Stunt Fall to a Bloody Death, First to Die From the Deadly Zombie Gaze - Rare Production Photos". LarryRay.com. Larry Ray. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q DeRossi, Giannetto; Trani, Maurizio (2015). "Making it Real: The Special Effects of The Beyond". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 2. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ Simpson 2018, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e Weingarten, Christopher R.; et al. (26 October 2016). "35 Greatest Horror Soundtracks". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (27 October 2015). "Frizzi 2 Fulci: A Look at Composer Fabio Frizzi's Work with Director Lucio Fulci". ComingSoon.net. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ L'Aldila (Vinyl LP). Beat Records Company. 1981. LPF 052.

- ^ The Beyond: Original Motion Picture Score (Vinyl LP). Death Waltz. 2015. ASIN B0170KG1HS. DW031LP.

- ^ The Beyond: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (CD). Dagored Records. 2001. ASIN B00005N84Q.

- ^ "The Beyond issue 1 Extras Revealed on sale Next Friday Oct 25th". 17 October 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ Firsching, Robert. "The Beyond". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Curti 2019, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Howarth 2015, p. 225.

- ^ Stine 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Curti 2019, p. 72.

- ^ a b Weldon 1996, p. 493.

- ^ Muir 2012b, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f Levene, Terry (2015). "Beyond Italy: Louis Fuller and the Seven Doors of Death". The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 2. Grindhouse Releasing. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ Grant 1999, p. 29.

- ^ "Movies". New York Daily News. New York City. 11 November 1983. p. 119 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Images from The Beyond. The Beyond (Blu-ray). Disc 1. Grindhouse Releasing. 2015. OCLC 959418475.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Mark (8 April 1998). "Rolling Thunder, Grindhouse and Cowboy Go 'Beyond' Dinner and a Movie, To Midnight". IndieWire. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "The Beyond (1981)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Squires, John (19 April 2017). "There Was a Shot from Fulci's 'The Beyond' in Raimi's 'Spider-Man'?!". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Barton, Steve (29 January 2015). "The Beyond's Coast-to-Coast Trek Rolls On". Dread Central. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Howarth 2015, p. 223.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (1 May 1984). "'Fire' and 'Death' a Pair of Silly Scarers". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelley, Bill (24 January 1984). "'Doors of Death' should be under lock and key". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. p. 6D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Connor, Bill (16 March 1985). "Film 'Seven Doors of Death' just isn't worth your time". Akron Beacon Journal. Akron, Ohio. p. A8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Ebert 2000, pp. 41–42.

- ^ "E tu vivrai nel terrore - L'aldilà (The Beyond) (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Guarisco, Donald. "The Beyond (1981)". AllMovie. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "The Beyond (1981)". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Muir 2012a, pp. 351–352.

- ^ a b Gibron, Bill (15 October 2007). "Lucio Fulci's The Beyond (1981)". PopMatters. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Tom Huddleston; Cath Clarke; Dave Calhoun; Nigel Floyd; Alim Kheraj; Phil de Semlyen (1 October 2019). "The 100 best horror films - the scariest movies ranked by experts". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

Tom Huddleston; Cath Clarke; Dave Calhoun; Nigel Floyd (19 September 2016). "The 100 best horror films". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2014.The best horror films and movies of all time, voted for by over 100 experts including Simon Pegg, Stephen King and Alice Cooper

- ^ Schneider 2009, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Tyner, Adam (3 October 2000). "The Beyond". DVD Talk. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ The Beyond (DVD). Anchor Bay Entertainment. 2000. OCLC 55591908.

- ^ Seven Doors of Death (DVD). Diamond Entertainment. 2000. OCLC 74454943.

- ^ "Cinema Cult: The Beyond at EzyDVD". EzyDVD. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Barton, Steve (7 January 2015). "Grindhouse Releasing's The Beyond Blu-ray Detailed". Dread Central. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Seven Doors of Death". Amazon Video. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "The Beyond Blu-Ray - Shameless Films". Shameless Screen Entertainment. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

Works cited

[edit]- Curti, Roberto (2019). Italian Gothic Horror Films, 1980-1989. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476672434.

- Dixon, Wheeler W. (2000). The Second Century of Cinema: The Past and Future of the Moving Image. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-791-44516-7.

- Ebert, Roger (2000). I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie. Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-740-70672-1.

- Fonseca, Anthony J. (2014). Pullium, Michele; Fonseca, Anthony J. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Zombie: The Walking Dead in Popular Culture and Myth: The Walking Dead in Popular Culture and Myth. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-440-80389-5.

- Grant, Edmond (1999). The Motion Picture Guide: 1999 Annual (The Films of 1998). Chicago: CineBooks. ISBN 978-0-933-99743-1.

- Howarth, Troy (2015). Splintered Visions: Lucio Fulci and His Films. Parkville, Maryland: Midnight Marquee Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-936-16853-8.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2012a). Horror Films of the 1980s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-786-45501-0.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2012b). The Films of John Carpenter. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-49348-7.

- O'Brien, Shelley F. (2011). "Killer Priests: The Last Taboo?". In Hansen, Regina (ed.). Roman Catholicism in Fantastic Film: Essays on Belief, Spectacle, Ritual and Imagery. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 256–267. ISBN 978-0-786-48724-0.

- Schneider, Steven Jay (2009). 101 Horror Movies You Must See Before You Die. London: Apple Press. ISBN 978-1-845-43656-8.

- Simpson, Phillip L. (2018). ""No one who sees it lives to describe it": The Book of Eibon and the Power of the Unseeable in Lucio Fulci's The Beyond". In Miller, Cynthia J.; Van Riper, A. Bowdoin (eds.). Terrifying Texts: Essays on Books of Good and Evil in Horror Cinema. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 245–254. ISBN 978-1-476-63374-9.

- Stine, Scott Aaron (2003). The Gorehound's Guide to Splatter Films of the 1980s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-41532-8.

- Weldon, Michael (1996). The Psychotronic Video Guide To Film. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-13149-4.