The Evil of Frankenstein

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The Evil of Frankenstein | |

|---|---|

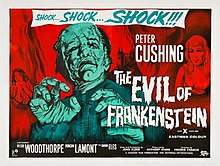

UK quad poster | |

| Directed by | Freddie Francis |

| Screenplay by | John Elder[1] |

| Based on | Victor Frankenstein by Mary Shelley |

| Produced by | Anthony Hinds[1] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Wilcox[1] |

| Edited by | James Needs[1] |

| Music by | Don Banks[1] |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Rank Film Distributors[2] (UK) Universal Pictures[1] (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 84 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom[2] |

| Budget | £130,000[1] |

The Evil of Frankenstein is a 1964 British film directed by Freddie Francis and starring Peter Cushing, Sandor Elès and Kiwi Kingston.[3] The screenplay was by Anthony Hinds (as John Elder). It is the third instalment in Hammer's Frankenstein series.

Plot

[edit]A child witnesses an intruder steal the corpse of one of her recently deceased relatives. Terrified, she flees from the cabin where she is hiding, and encounters Baron Victor Frankenstein. As the body snatcher takes the corpse to Victor's secret laboratory, a local priest discovers the theft. The child identifies both the body snatcher and his employer. Forced to leave town, Victor and his assistant Hans return to the Baron's hometown of Karlstaad, where they plan to sell valuables from the abandoned Frankenstein chateau to fund new work. Arriving in the village, they rescue a deaf-mute young woman from being harassed by a gang of thugs. Arriving at the chateau, they find all the valuables stolen and flee.

The following day, Victor and Hans blend in with a local carnival in order to remain incognito. While visiting a local pub, Victor notices the local burgomaster is wearing one of his valuables; a ring. Victor causes a scene, is immediately recognized by the authorities, and flees once again, eventually hiding at the exhibit of a hypnotist named Zoltan. Zoltan clashes with the police and is arrested, covering the escape of Victor and Hans. Later that evening, Victor and Hans break into the burgomaster's apartments to retrieve the valuables, but the police arrive. They flee once more and encounter the deaf-mute girl. She leads them to her shelter in a cave.

Victor finds his prototype creation frozen in ice in the cave. He and Hans build a fire to melt the ice and free the creature. They take it to the chateau and restore it to life. However, the creature's brain is unresponsive. Victor, desperate to restore active consciousness to his creation, comes up with the idea of obtaining the services of Zoltan to reanimate the creature's mind. Zoltan has been banished from Karlstaad for not having a license to perform. After clever psychological manipulation by Victor, he agrees to the task.

Zoltan is successful but has less than scientific interests at heart. With the creature responding only to his commands, Zoltan uses it to rob and take revenge upon the town's authorities. Victor evicts Zoltan, who then instructs the creature to kill Victor, but the creature kills Zoltan instead. The creature goes into a fit of rage and accidentally sets the lab on fire. Hans escapes with the girl, and the couple watch as smoke pours from the chateau. A massive explosion ensues, causing the section where the lab was to topple over the cliff, killing Victor and the creature.

Cast

[edit]- Peter Cushing as Baron Victor Frankenstein

- Kiwi Kingston as the Creature

- Peter Woodthorpe as Zoltan

- Sandor Elès as Hans

- Duncan Lamont as Chief of Police

- David Hutcheson as Burgomaster of Karlstaad

- Katy Wild as Beggar girl

- James Maxwell as priest

- Howard Goorney as drunk

- Anthony Blackshaw as policeman

- David Conville as policeman

- Caron Gardner as burgomaster's wife

Production

[edit]

The script for the film by Anthony Hinds was based on a story synopsis that Peter Bryan submitted in May 1958 for the aborted Tales of Frankenstein television series.[4] The film breaks continuity from the preceding film, The Revenge of Frankenstein.[5] Denis Meikle described the break: "Any pretext of a connection to The Revenge of Frankenstein is dispensed with in a brazen display of contempt for continuity. A flashback creates a prior history that is wholly unrelated to the last Sangster script and is instead plundered from Universal's Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman."[6]

The film was in production from 14 October to 16 November 1963 at Bray Studios in Windsor, Berkshire and on location at Black Park Country Park in Wexham, Buckinghsamshire.[7] The film was made during Hammer's six-year co-production pact with Columbia Pictures.[4] This led to the company to make a few productions a year with Universal Pictures, with The Evil of Frankenstein being the only film that Hammer made that was financed by Universal in 1963.[4] The film's version of the Monster is noted for resembling the one in Universal Pictures' original Frankenstein series of the 1930s and 1940s, including the distinctive laboratory sets as well as the flat-headed look of Jack Pierce's monster make-up which had been designed for Boris Karloff.[8] Earlier Frankenstein films by Hammer had studiously avoided such similarities for copyright reasons. However, a new film distribution deal had been made between Hammer and Universal. As a result, Hammer had free rein to duplicate make-up and set elements.[8]

Additional scenes for American television were filmed on 14 January 1966 at Universal Studios in Los Angeles adding a new subplot featuring Steven Geray, Maria Palmer and William Phipps, who had not appeared in the original version.[4][9]

Release

[edit]The Evil of Frankenstein had its premiere in London on 19 April 1964 at the New Victoria Theatre.[1] It received a general release in the country on 31 May 1964.[1] It later received a release in the United States by Universal Pictures on 8 May 1964.[1]

Television version

[edit]The film was shown on NBC in the United States as part of their NBC Saturday Night at the Movies on 2 January 1968 with two additional scenes, extending the running time to 97 minutes.[1][9]

Critical reception

[edit]From contemporary reviews, Howard Thompson of The New York Times wrote, "For the first half, the latest Frankenstein go-round has a succinct pull and a curious dignity ... the picture begins to say something about superstition and hypocrisy. Then it simply goes hog-wild (monster gets drunk) and heads for the ash heap."[10]

Variety gave the film a lukewarm review, writing that the direction was "deft enough over the more preposterous patches" and that there was "always something going on," but that the dialogue sometimes provoked unintended laughter and that some of the supporting cast "tend to ham it up to the make-believe's detriment."[11]

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that the monster made "a welcome return to tradition in a close approximation of Boris Karloff's celebrated make-up" and that the Baron's lab equipment was "as photogenic as ever," but that the film was "sadly tatty" in all other respects, concluding: "Saddled with an uninspiring cast, and a Bavarian village so stagy that the villagers rhubarbing away into their Olde German beermugs seem almost real by comparison, Freddie Francis finds the going too uphill by half."[2]

From retrospective reviews, AllMovie's review of the film was mixed to negative, calling it "dismal" and "the worst of Hammer Films' Frankenstein series".[12] As of June 2020[update] the film has an average critic's approval of 57% on Rotten Tomatoes.[13]

See also

[edit]- Frankenstein in popular culture

- List of films featuring Frankenstein's monster

- Frankenstein (Hammer film series)

- Hammer filmography

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fellner 2019, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d "Evil of Frankenstein, The". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 31, no. 365. British Film Institute. June 1964. p. 92.

- ^ "The Evil of Frankenstein". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Fellner 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Hallenbeck 2013, p. 135.

- ^ Meikle 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Fellner 2019, p. 80.

- ^ a b Hallenbeck 2013, p. 124-126.

- ^ a b "The Newest 'Evil': Shoot Scenes To Pad Pic for TV". Variety. 17 January 1968. p. 1.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (18 June 1964). "'Evil of Frankenstein' and 'Nightmare'". The New York Times. p. 29.

- ^ "The Evil of Frankenstein". Variety. 22 April 1964. p. 6.

- ^ Robert Firsching. "The Evil of Frankenstein – Review". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "The Evil of Frankenstein (1964)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Fellner, Chris (2019). The Encyclopedia of Hammer Films. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1538126592.

- Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2013), The Hammer Frankenstein: British Cult Cinema, Midnight Marquee Press, ISBN 978-1936168330

- Meikle, Denis (2008), A History of Horrors: The Rise and Fall of the House of Hammer, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 9780810863811