The Inner Light (song)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| "The Inner Light" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

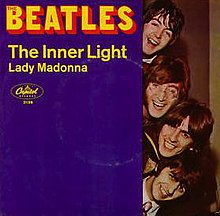

US picture sleeve (reverse) | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| A-side | "Lady Madonna" | |||

| Released | 15 March 1968 | |||

| Recorded | 13 January, 6 and 8 February 1968 | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | Indian music, raga rock | |||

| Length | 2:36 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison | |||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"The Inner Light" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, written by George Harrison. It was released on a non-album single in March 1968, as the B-side to "Lady Madonna". The song was the first Harrison composition to be issued on a Beatles single and reflects the band's embrace of Transcendental Meditation, which they were studying in India under Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at the time of the single's release. After "Love You To" and "Within You Without You", it was the last of Harrison's three songs from the Beatles era that demonstrate an overt Indian classical influence and are styled as Indian pieces. The lyrics are a rendering of chapter 47[1] from the Taoist Tao Te Ching, which he set to music on the recommendation of Juan Mascaró, a Sanskrit scholar who had translated the passage in his 1958 book Lamps of Fire.

Harrison recorded the instrumental track for "The Inner Light" in Bombay in January 1968, during the sessions for his Wonderwall Music soundtrack album. It is the only Beatles studio recording to be made outside Europe and introduced Indian instruments such as sarod, shehnai and pakhavaj to the band's sound. The musicians on the track include Aashish Khan, Hanuman Jadev and Hariprasad Chaurasia. Aside from Harrison's lead vocal, recorded in London, the Beatles' only contribution came in the form of group backing vocals over the song's final line. In the decade following its release, the song became a comparative rarity among the band's recordings; it has subsequently appeared on compilation albums such as Rarities; Past Masters, Volume Two; and Mono Masters. It is the only Beatles song to never appear on any official Beatles album.

"The Inner Light" has received praise from several music critics and musicologists for its melodic qualities and its evocation of the meditation experience. Jeff Lynne and Anoushka Shankar performed the song at the Concert for George tribute in November 2002, a year after Harrison's death. An alternative take of the 1968 instrumental track was released in 2014 on the remastered Wonderwall Music CD. Screenwriter Morgan Gendel named a 1992 episode of the television series Star Trek: The Next Generation as an homage to the song. In 2020, Harrison's Material World Foundation announced The Inner Light Challenge, an initiative to raise funds for the MusiCares COVID-19 Relief Fund, Save the Children and Médecins Sans Frontières in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background and inspiration

[edit]The song was written especially for Juan Mascaró because he sent me the book [Lamps of Fire] and is a sweet old man. It was nice, the words said everything. Amen.[2]

– George Harrison, 1979

In his autobiography, I, Me, Mine, George Harrison recalls that he was inspired to write "The Inner Light" by Juan Mascaró, a Sanskrit scholar at Cambridge University.[2][3] Mascaró had taken part in a debate, televised on The Frost Programme on 4 October 1967,[4] during which Harrison and John Lennon discussed the merits of Transcendental Meditation with an audience of academics and religious leaders.[5][6] In a subsequent letter to Harrison, dated 16 November, Mascaró expressed the hope that they might meet again before the Beatles departed for India,[7] where the group were to study meditation with their guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.[8] Mascaró enclosed a copy of his book Lamps of Fire, an anthology of religious writings,[9] including from Lao-Tzu's Tao Te Ching.[10] Having stated his admiration for the spiritual message in Harrison's composition "Within You Without You",[11] Mascaró enquired: "might it not be interesting to put into your music a few words of Tao, for example no. 48, page 66 of Lamps?"[7][nb 1]

Harrison wrote the song during a period when he had undertaken his first musical project outside the Beatles, composing the soundtrack to the Joe Massot-directed film Wonderwall,[14][15] and continued to study the Indian sitar, partly under the tutelage of Ravi Shankar.[16][17] When writing "The Inner Light", he made minimal alterations to the translated Lao-Tzu text[3][18] and used the same title that Mascaró had used.[9] In I, Me, Mine, Harrison says of the changes required to create his second verse:

In the original poem, the verse says "Without going out of my door, I can know the ways of heaven." And so to prevent any misinterpretations – and also to make the song a bit longer – I did repeat that as a second verse but made it: "Without going out of your door / You can know all things on earth / Without looking out of your window / You can know the ways of heaven" – so that it included everybody.[2]

After "Within You Without You", "The Inner Light" was the second composition to fully reflect Harrison's immersion in Eastern spiritual concepts, particularly meditation,[19][20] an interest that had spread to his Beatles bandmates[21][22] and to the group's audience and peers.[23][24] The lyrics espouse meditation as a means to genuine understanding.[25] Theologian Dale Allison describes the song as a "hymn" to quietism and comments that, in their attempt to "relativize and disparage knowledge of the external world", the words convey Harrison's enduring worldview.[26] Author John Winn notes that Harrison had presaged the message of "The Inner Light" in an August 1967 interview, when he told New York DJ Murray Kaufman: "The more you learn, the more you know that you don't know anything at all."[27] Writing in his study of Harrison's musical career, Ian Inglis similarly identifies a precedent in the song "It's All Too Much", where Harrison sings: "The more I learn, the less I know."[28]

Composition and musical structure

[edit]

"The Inner Light" was Harrison's third song in the Indian musical genre,[29] after "Love You To" and "Within You Without You".[30] While those earlier songs had followed the Hindustani (North Indian) system of Indian classical music, as sitar- and tabla-based compositions, "The Inner Light" is closer in style to the Carnatic (or South Indian) temple music tradition.[31] Harrison's progression within the genre reflected his concept for the Wonderwall soundtrack[32] – namely, that the assignment allowed him to create an "anthology" of Indian music[33][34] and present a diverse range of styles and instrumentation.[11][35]

The composition is structured into three instrumental passages separated by two sections of verse.[36] The buoyant mood of the instrumental sections – set to what author Peter Lavezzoli describes as "a raucous 4/4 rhythm"[12] – contrasts with the gentle, meditative portions containing the verses.[29][37] The contrast is reflected in the lead instruments that Harrison would use on the recording: whereas sarod and shehnai, supported by pakhavaj, are prominent during the musical passages, the softer-sounding bansuri (bamboo flute)[37] and harmonium accompany the singing over the verses, as the sarod provides a response to each line of the vocal.[38] In the last instrumental section, Harrison incorporates the conclusion of Lao-Tzu's poem,[31] beginning with the line "Arrive without travelling".[39]

The melody conforms to the pitches of Mixolydian mode, or its Indian equivalent, the Khamaj thaat.[40] Musicologist Dominic Pedler writes that the tune features unusual tritone intervals, which, together with the musical arrangement, ensure that the song is far removed from standard "pop tunes".[41] In a further departure from Harrison's previous forays into Indian music, both of which made extensive use of single-chord drone, the melody allows for formal chord changes: over the verses, the dominant E♭ major alternates with F minor, before a move to A♭ over the line "The farther one travels the less one knows".[42]

In the opening words ("Without going out"), the melody uses what Pedler terms a "hauntingly modal" G-B♭-D♭ tritone progression as, within the song's tonic key (of E♭), the 3rd note heads towards the flat 7th.[41] Musicologist Walter Everett likens this ascending arpeggiation of the diminished triad to a melodic feature in "Within You Without You" (over that song's recurring phrase "We were talking").[43] "The Inner Light" is an example of Harrison creating ambiguity about the tonic key, a technique that Pedler recognises as a characteristic of Harrison's spiritually oriented songwriting.[41]

Recording

[edit]Bombay

[edit]

Having used London-based Indian musicians from the Asian Music Circle on "Love You To" and "Within You Without You",[44] Harrison recorded "The Inner Light" in India with some of the country's foremost contemporary classical players.[45] In early January 1968, he travelled to HMV Studios[11][46] in Bombay to record part of the score for Wonderwall,[6][47] much of which would appear on his debut solo album, Wonderwall Music.[48] The day after completing the soundtrack recordings, on 13 January,[49] Harrison taped additional pieces for possible later use, one of which was the instrumental track for "The Inner Light".[50] Five takes of the song were recorded on a two-track recorder.[51]

The musicians at the sessions were recruited by Shambhu Das, who had assisted in Harrison's sitar tuition on his previous visit to Bombay, in 1966,[52] and Vijay Dubey, the head of A&R for HMV Records in India.[53] According to Lavezzoli and Beatles biographer Kenneth Womack, the line-up on the track was Aashish Khan (sarod), Mahapurush Misra (pakhavaj), Hanuman Jadev (shehnai), Hariprasad Chaurasia (bansuri) and Rijram Desad (harmonium).[12][54] In Lavezzoli's view, although these instruments are more commonly associated with the Hindustani discipline, the performers play them in a South Indian style, which adds to the Carnatic identity of the song.[12] He highlights the manner in which the sarod, traditionally a lead instrument in North India, is played by Khan: staccato-style in the upper register, creating a sound more typical of acoustic guitar. Similarly, the pakhavaj is performed in the style of a South Indian tavil barrel drum, and the sound of the double-reed shehnai is closer to that of its Southern equivalent, the nagaswaram.[12] The recording includes tabla tarang[43] over the quiet, vocal interludes.[55]

Author Simon Leng refutes the presence of the oboe-like shehnai, however, saying that this part was played on an esraj, a bow-played string instrument.[55] Citing Khan's recollection that he only worked with Harrison in London, Leng also says that the sarod was added to the track later.[55] Rather than esraj, which Leng gives for "The Inner Light" and for Wonderwall tracks such as "Crying",[56] Harrison used the bow-played tar shehnai during the Bombay sessions,[35][57] played by Vinayak Vora.[51][58][nb 2] As with the Wonderwall selections recorded at HMV, Harrison directed the musicians[54][60] but did not perform on the instrumental track.[12]

London

[edit]Harrison completed the song in London during sessions for a new Beatles single,[61] which was intended to cover their absence while the group were in Rishikesh, India, with the Maharishi.[62][63] Once the Bombay recording had been transferred to four-track tape,[64] Harrison recorded his vocal part for "The Inner Light" on 6 February, at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios).[65][66] Lacking confidence in his ability to sing in so high a register, he had to be coaxed by Lennon and Paul McCartney into delivering the requisite performance.[31] Two days later, McCartney and Lennon overdubbed backing vocals at the very end of the song,[67] over the words "Do all without doing".[64]

"The Inner Light" was held in high regard by Harrison's bandmates,[6] particularly McCartney,[41] and was selected as the B-side for the forthcoming single.[68] It was the first Harrison composition to appear on a Beatles single,[69][70] in addition to being the only Beatles studio recording made outside Europe.[31] Everett writes that Lennon's admiration for the track was evident from his subsequent creation of the song "Julia" through "a very parallel process" – in that instance, by adapting a work by Kahlil Gibran.[43][nb 3] Although Harrison had served as the producer at the Bombay session, only George Martin received a production credit for "The Inner Light".[74]

Release

[edit]Forget the Indian music and listen to the melody. Don't you think it's a beautiful melody? It's really lovely.[69]

– Paul McCartney, 1968

The song was issued as the B-side of "Lady Madonna" on 15 March 1968 in the UK,[75] with the US release following three days later.[76] While Chris Welch of Melody Maker expressed doubts about the hit potential of the A-side,[77][78] Billboard magazine commented on the aptness of "The Inner Light", given the band's concurrent "meditation spell".[79] Cash Box's reviewer wrote: "Lyrics from the transcendental meditation school and near-Eastern orchestrations on a very interesting coupler that could show sales as strong as ['Lady Madonna']."[80] In America, the song charted independently on the Billboard Hot 100 for one week,[81] placing at number 96.[82][83] In Australia, it was listed with "Lady Madonna", as a double A-side, when the single topped the Go-Set national chart.[84]

In the description of author and critic David Quantick, whereas "Lady Madonna" represented a departure from the Beatles' psychedelic productions of the previous year, "The Inner Light" was an "accurate indication" of the group's mindset in Rishikesh.[85] Paul Saltzman, a Canadian film-maker who had been inspired by the Beatles' adoption of Indian musical and philosophical themes,[37] joined the band at the Maharishi's ashram and recalls hearing the song there for the first time.[86] He said he found Harrison's perspective on meditation profoundly moving,[87] particularly when Harrison told him that, while the Beatles had achieved wealth and fame in abundance, "It isn't love. It isn't health. It isn't peace inside, is it?"[88][89]

The Beatles' 1968 visit to Rishikesh resulted in a surge of interest in Indian culture and spirituality among Western youth,[90][91] but it also marked the end of the band's overtly Indian phase.[92][93] From June that year, Harrison abandoned his efforts to master the sitar and returned to the guitar as his principal instrument.[94][95][nb 4] In an interview in September, Harrison discussed his renewed interest in rock music and described "The Inner Light" as "one of my precious things".[99]

Critical reception

[edit]Author Nicholas Schaffner wrote in 1977 that "The Inner Light" "proved to be the best – and last" example of Harrison directly incorporating Indian music into the Beatles' work.[69] Schaffner paired it with "Within You Without You" as raga rock songs that "feature haunting, exquisitely lovely melodies", and as two pieces that could have been among Harrison's "greatest achievements" had they been made with his bandmates' participation.[100] Bruce Eder of AllMusic describes the same tracks as "a pair of beautiful songs … that were effectively solo recordings".[101] Ian MacDonald likens the song's "studied innocence and exotic sweetness" to recordings by the Incredible String Band and concludes: "'The Inner Light' is both spirited and charming – one of its author's most attractive pieces."[6]

Writing for Mojo magazine in 2003, John Harris similarly admired it as Harrison's "loveliest addition of Indian music to The Beatles' repertoire".[102] In Ian Inglis' view: "it is the extraordinary synthesis of separate musical and lyrical traditions (in this case, Indian instrumentation, Chinese philosophy, and Western popular music) that distinguishes the song. Harrison's uncharacteristically warm vocal weaves in and around the delicate, almost fragile, melody to deliver a simple testimony to the power of meditation ..."[103] With regard to the song's influence, Inglis recognises Harrison's espousal of Eastern spirituality as "a serious and important development that reflected popular music's increasing maturity", and a statement that prepared rock audiences for later religious pronouncements by Pete Townshend, Carlos Santana, John McLaughlin, Cat Stevens and Bob Dylan.[104]

Nick DeRiso of the music website Something Else! considers "The Inner Light" to be one of its composer's "most successful marriages of raga and rock" and, through Harrison's introduction of instruments such as sarod, shehnai and pakhavaj, a key recording in the evolution of the 1980s world music genre.[105] While admiring the song's transcendent qualities, Everett quotes the ethnomusicologist David Reck, who wrote in 1988: "Most memorable is the sheer simplicity and straightforwardness of the haunting modal melody, somehow capturing perfectly the mood and truth and aphoristic essence of the lyrics."[43]

Later releases

[edit]A stereo mix of "The Inner Light" was created at Abbey Road on 27 January 1970[106] for what Beatles recording historian Mark Lewisohn terms "some indefinable future use".[107][nb 5] On this later mix, the opening instrumental section differs slightly from that on the original, mono version.[68]

Following its initial release in 1968, "The Inner Light" became one of the rarest Beatles recordings.[29] Although it appeared on Por Siempre Beatles, a 1971 Spanish compilation album,[109] the song was not available on a British or American album until its inclusion on Rarities,[110][111] which was originally issued as a disc in the 1978 box set The Beatles Collection before receiving an independent UK release.[112] The 1980 US compilation titled Rarities also featured "The Inner Light",[113] again in its mono form.[114] The stereo mix was first released as the opening track on a bonus EP, titled The Beatles,[115] issued in the UK in December 1981 as part of The Beatles EP Collection.[107] The song was issued on CD in 1988, in stereo, on Past Masters, Volume Two.[116] The mono mix was subsequently included on the Beatles' Mono Masters compilation.[117]

For the Beatles' 2006 remix album Love, created for the Cirque du Soleil stage show, the song was segued onto the end of "Here Comes the Sun".[118][119] This mashup begins with Harrison singing "Here Comes the Sun" over the tabla part from "Within You, Without You"[120] and ends with Indian instrumentation from "The Inner Light".[121]

In 2014, an alternative instrumental take of the song was issued as a bonus track on Harrison's Wonderwall Music remastered CD.[122][123] The recording begins with a short studio discussion,[105] as Harrison instructs the Bombay musicians.[124][nb 6]

Cover versions and popular culture

[edit]Having covered "Within You Without You" in 1967,[126] the Soulful Strings included "The Inner Light" on their album Another Exposure the following year.[127] Junior Parker recorded the song,[68] releasing a version on his 1971 album with Jimmy McGriff, The Dudes Doin' Business.[128] Later in the 1970s, the song's title was appropriated for one of the first international Beatles fanzines.[129][nb 7]

Concert for George performance

[edit]

Jeff Lynne, who worked frequently with Harrison after the Beatles' break-up, sang "The Inner Light" at the Concert for George tribute,[131] held at London's Royal Albert Hall on 29 November 2002, a year after the former Beatle's death.[132] In what Simon Leng describes as "a wonderfully eloquent duet", Lynne performed the song with Anoushka Shankar,[133] who played the original sarod part on sitar.[134] Lynne and Shankar were accompanied by Harrison's son Dhani (on keyboards and backing vocals) and an ensemble of Indian musicians that included percussionist Tanmoy Bose (on dholak), Rajendra Prasanna (shehnai) and Sunil Gupta (flute).[134]

The song appeared partway through the concert's opening, Indian music segment,[135] which was performed by Shankar and otherwise composed by her father, Ravi Shankar,[132][134] who had continued to be Harrison's friend and mentor until his death.[136] Inglis comments that, in its context at the Concert for George, "['The Inner Light'] does not appear at all out of place among the Indian folk and classical compositions that surround it."[137] Reviewing the Concert for George film for The Guardian, James Griffiths admired Lynne's reading of the song as a "particularly sublime version".[138]

Star Trek: The Next Generation episode

[edit]In June 1992, the American television series Star Trek: The Next Generation aired an episode titled "The Inner Light",[139] which went on to win the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[140][141] The plot centres on the show's main character, Captain Jean-Luc Picard, temporarily living in a dream-like state on an unfamiliar planet, during which decades elapse relative to a few minutes in reality.[139] An avowed fan of the Beatles, screenwriter Morgan Gendel titled the episode after Harrison's song.[142]

In an email to the Star Trek blog site Soul of Star Trek, Nick Sagan, another of the show's screenwriters, suggested that the song's lyrics express the "ability to experience many things without actually going anywhere – and that's what happens to Picard". In his subsequent post on the same site, Gendel confirmed this similarity, saying that the Beatles track "captured the theme of the show: that Picard experienced a lifetime of memories all in his head".[143] When discussing the episode on the official Star Trek website in 2013, Gendel concluded: "If you Google 'Inner Light + song' you’ll get the Beatles tune and an acknowledgment of my TNG homage to it back-to-back … that might be the best gift my authorship of this episode has given me."[144]

The Inner Light Challenge 2020

[edit]In 2020, Harrison's Material World Foundation announced The Inner Light Challenge, an initiative to raise funds for the MusiCares COVID-19 Relief Fund, Save the Children and Médecins Sans Frontières in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Foundation pledged to donate up to $100,000 for each "'Inner Light' moment" shared on social media, whether a portion or a single line from the song.[145]

Dhani Harrison posted a performance of "The Inner Light" on Facebook, while Harrison's widow, Olivia, said of the song: "These lyrics sung by George are a positive reminder to all of us who are isolating, in quarantine or respecting the request to shelter in place. Let's get and stay connected at this difficult time. There are things we can do to help and we invite you to share your Inner Light."[145]

Personnel

[edit]According to Peter Lavezzoli[146] and Kenneth Womack,[54] except where noted:

The Beatles

- George Harrison – lead vocals, direction

- John Lennon – harmony vocals

- Paul McCartney – harmony vocals

Additional musicians

- Aashish Khan – sarod

- Hanuman Jadev – shehnai

- Hariprasad Chaurasia – bansuri

- Mahapurush Misra – pakhavaj

- Rijram Desad – harmonium

- uncredited – tabla tarang[43][147]

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1968) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot 100[148] | 96 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ The poem to which Mascaró referred, which is the 48th item in Lamps of Fire,[12] is chapter 47 of the Tao Te Ching.[13]

- ^ As reproduced on Harrison's website, music journalist Matt Hurwitz also gives a different line-up of instruments. He lists harmonium, tar shehnai, sitar, dholak (a double-headed hand drum, similar to the pakhavaj), two flutes, and a bulbul tarang as the song's lead string instrument, rather than sarod. Hurwitz says the bulbul tarang player was most likely Shambhu Das or Indril Bhattacharya.[59]

- ^ The Beatles chose "The Inner Light" as the B-side over Lennon's "Across the Universe",[71][72] the melody for which music journalist Gary Pig Gold considers was inspired by Harrison's composition.[73]

- ^ While filming Raga together in June 1968, Shankar urged Harrison not to ignore his musical roots.[96] This advice, together with Harrison's realisation that he would never match the standard of Shankar's top students, who had dedicated themselves to learning the sitar from a young age, led to his decision to re-engage with the guitar.[97][98]

- ^ According to Everett, the song was most likely under consideration for the 1970 US compilation album Hey Jude.[108]

- ^ The reissue also includes the previously unreleased "Almost Shankara", another piece that Harrison recorded in Bombay in 1968.[125]

- ^ While noting the plethora of such publications, particularly in America, Schaffner describes The Inner Light as "excellent" and singles it out for the thoroughness of its discographical information.[130]

References

[edit]- ^ Lao Tzu. "Tao Te Ching". Wikisource. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Harrison 2002, p. 118.

- ^ a b Allison 2006, p. 38.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 130.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d MacDonald 1998, p. 240.

- ^ a b Harrison 2002, p. 119.

- ^ Greene 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Turner 1999, p. 147.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 182–83.

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d e f Lavezzoli 2006, p. 183.

- ^ Tao Te Ching the inner light; [chapter] 47; an artistbook. WorldCat. OCLC 935040084. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Leng 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 283.

- ^ Harrison 2002, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 180, 184.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Tillery 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Inglis 2010, pp. 11, 139.

- ^ Jones, Nick (16 December 1967). "Beatle George and Where He's At". Melody Maker. pp. 8–9. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ MacDonald 1998, p. 185.

- ^ The Editors of Rolling Stone 2002, p. 36.

- ^ Goldberg 2010, pp. 119, 157.

- ^ Greene 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Allison 2006, pp. 26, 27.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Inglis 2010, pp. 10, 11.

- ^ a b c Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'The Inner Light'". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 178, 182.

- ^ a b c d Lavezzoli 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Leng 2006, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Clayson 2003, p. 235.

- ^ George Harrison, in The Beatles 2000, p. 280.

- ^ a b White, Timothy (November 1987). "George Harrison – Reconsidered". Musician. p. 56.

- ^ Pollack, Alan W. (1997). "Notes on 'The Inner Light'". soundscapes.info. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Greene 2006, p. 92.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 183–84.

- ^ Harrison 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 112, 153.

- ^ a b c d Pedler 2003, p. 524.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 175, 178, 183.

- ^ a b c d e Everett 1999, p. 153.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, pp. 172, 214.

- ^ Leng 2006, pp. 33–34, 48.

- ^ Howlett 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Tillery 2011, p. 161.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 420.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 291.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 419.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2005, p. 132.

- ^ Clayson 2003, pp. 206, 235.

- ^ Howlett 2014, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ a b c Womack 2014, p. 467.

- ^ a b c Leng 2006, pp. 34, 34fn.

- ^ Leng 2006, pp. 34fn, 49.

- ^ Telegram to Shambhu Das, in The Beatles 2000, p. 280.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 198.

- ^ Hurwitz, Matt. "Wonderwall Music". georgeharrison.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Howlett 2014, p. 10.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, pp. 240–41.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 232.

- ^ Quantick 2002, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 133.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2013, pp. 446–47.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 133, 134.

- ^ a b c Fontenot, Robert. "The Beatles Songs: 'The Inner Light' – The history of this classic Beatles song". oldies.about.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Schaffner 1978, p. 95.

- ^ Tillery 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 134.

- ^ Shea & Rodriguez 2007, p. 188.

- ^ Gold, Gary Pig (February 2004). "The Beatles: Gary Pig Gold Presents A Fab Forty". fufkin.com. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 446.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 295.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 67.

- ^ Welch, Chris (9 March 1968). "Beatles Recall All Our Yesterdays". Melody Maker. p. 17.

- ^ Sutherland, Steve, ed. (2003). NME Originals: Lennon. London: IPC Ignite!. p. 50.

- ^ Billboard Review Panel (16 March 1968). "Spotlight Singles". Billboard. p. 78. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Cash Box staff (16 March 1968). "Cash Box Record Reviews". Cash Box. p. 16.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 350.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 97.

- ^ Billboard staff (30 March 1968). "Billboard Hot 100 (for week ending March 30, 1968)". Billboard. p. 70. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Go-Set Australian charts – 8 May 1968". poparchives.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Quantick 2002, p. 20.

- ^ The Wire staff (2 November 2017). "When the Beatles Came to Rishikesh to Relax, Meditate and Write Some Classic Songs". The Wire. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Kilachand, Tara (17 May 2008). "Their humour was one way they kept their feet on the ground". Live Mint. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Greene 2006, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Telegraph staff (27 March 2005). "Long and winding road to Rishikesh" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph (India). Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ Goldberg 2010, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Morelli 2016, p. 349.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Greene 2006, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Leng 2006, pp. 32–33, 36.

- ^ Shea & Rodriguez 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Snow, Mat (November 2014). "George Harrison: Quiet Storm". Mojo. p. 69.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 184–85.

- ^ Harrison 2002, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Smith, Alan (21 September 1968). "George Is a Rocker Again!". NME. p. 3.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 68.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "George Harrison". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Harris, John (2003). "Back to the Future". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. p. 19.

- ^ Inglis 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Inglis 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b DeRiso, Nick (19 September 2014). "One Track Mind: George Harrison, 'The Inner Light (alt. take)' from The Apple Years (2014)". Something Else!. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 447.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2005, p. 196.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 341.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 213.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 467–68.

- ^ Allison 2006, p. 147.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, pp. 131–32.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 468.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, pp. 134–36.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 107.

- ^ Allison 2006, pp. 26, 147.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 647.

- ^ Irvin, Jim (December 2006). "The Beatles: Love (Apple)". Mojo. p. 100. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 317.

- ^ Book, John (9 March 2007). "The Beatles Love". Okayplayer. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Cole, Jenni (5 December 2006). "The Beatles – Love (EMI)". musicOMH. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (19 September 2014). "George Harrison, 'The Apple Years 1968–75' – Album Review". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Coplan, Chris (19 September 2014). "Listen to an alternate version of George Harrison's 'The Inner Light'". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Fricke, David (16 October 2014). "Inside George Harrison's Archives: Dhani on His Father's Incredible Vaults". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Marchese, Joe (23 September 2014). "Review: The George Harrison Remasters – 'The Apple Years 1968–1975'". The Second Disc. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Goble, Ryan Randall. "Soulful Strings Groovin' with the Soulful Strings". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ Magnus, Johnny (1968). Another Exposure (LP liner-note essay). The Soulful Strings. Cadet Records.

- ^ Christgau, Robert. "Jimmy McGriff and Junior Parker". robertchristgau.com. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 169–70.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 56, 170.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 591–92.

- ^ a b Inglis 2010, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Leng 2006, p. 309.

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 199.

- ^ Kanis, Jon (December 2012). "I'll See You in My Dreams: Looking Back at the Concert for George". San Diego Troubadour. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Tillery 2011, p. 141.

- ^ Inglis 2010, p. 125.

- ^ Griffiths, James (5 December 2003). "DVD: Concert for George". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ a b "Inner Light, The". startrek.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Chronicle". The New York Times. 7 September 1993. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2017. See also: "1993 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ Handlen, Zack (12 May 2011). "Star Trek: The Next Generation: 'The Inner Light'/'Time's Arrow, Part I'". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Thill, Scott (25 September 2012). "The Best and Worst of Star Trek: The Next Generation's Sci-Fi Optimism". Wired. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Inner Light Sources". Soul of Star Trek. June 2006. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Gendel, Morgan (2 July 2013). "'The Inner Light' Turns 21". startrek.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ a b "The Inner Light Challenge". materialworldfoundation.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 183, 184.

- ^ Leng 2006, p. 34fn.

- ^ "The Beatles Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Allison, Dale C. Jr. (2006). The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). George Harrison. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-489-3.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone (2002). Harrison. New York, NY: Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-3581-5.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512941-5.

- Goldberg, Philip (2010). American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation – How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. New York, NY: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-385-52134-5.

- Greene, Joshua M. (2006). Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3.

- Guesdon, Jean-Michel; Margotin, Philippe (2013). All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release. New York, NY: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-1-57912-952-1.

- Harrison, George (2002) [1980]. I, Me, Mine. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-5900-4.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Howlett, Kevin (2014). Wonderwall Music (CD liner-note essay). George Harrison. Apple Records.

- Inglis, Ian (2010). The Words and Music of George Harrison. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-2819-3.

- Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (1998). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6697-8.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Morelli, Sarah (2016). "'A Superior Race of Strong Women': North Indian Classical Dance in the San Francisco Bay Area". In Lornell, Kip; Rasmussen, Anne K. (eds.). The Music of Multicultural America: Performance, Identity, and Community in the United States. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-0374-0.

- Pedler, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8167-6.

- Quantick, David (2002). Revolution: The Making of the Beatles' White Album. Chicago, IL: A Cappella Books. ISBN 1-55652-470-6.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Shea, Stuart; Rodriguez, Robert (2007). Fab Four FAQ: Everything Left to Know About the Beatles … and More!. New York, NY: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-2138-2.

- Tillery, Gary (2011). Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5.

- Turner, Steve (1999). A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song (2nd edn). New York, NY: Carlton/HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-273698-1.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.

External links

[edit]- Full lyrics of the song at the Beatles' official website

- "The Beatles' magical mystery tour of India", Live Mint, 20 January 2018

- Harp & Plow's "Inner Light moment" for The Inner Light Challenge