The Titan's Goblet

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The Titan's Goblet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Thomas Cole |

| Year | 1833 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 49.2 cm × 41 cm (19+3⁄8 in × 16+1⁄8 in) |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

| Accession | 04.29.2 |

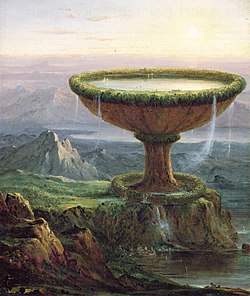

The Titan's Goblet is an oil painting by the English-born American landscape artist Thomas Cole. Painted in 1833, it is perhaps the most enigmatic of Cole's allegorical or imaginary landscape scenes. It is a work that "defies full explanation", according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[2] The Titan's Goblet has been called a "picture within a picture" and a "landscape within a landscape": the goblet stands on conventional terrain, but its inhabitants live along its rim in a world all their own. Vegetation covers the entire brim, broken only by two tiny buildings, a Greek temple and an Italian palace. The vast waters are dotted with sailing vessels. Where the water spills upon the ground below, grass and a more rudimentary civilization spring up.

Interpretations

[edit]Cole often provided text to accompany his paintings, but did not comment on The Titan's Goblet, leaving his intentions open to debate. In the 1880s, one interpretation related Cole's goblet to the world tree and specifically to the Yggdrasil in Norse mythology. A 1904 auction catalog continued this theme, writing "the spiritual idea in the centre of the painting, conveying the beautiful Norse theory that life and the world is but a tree with ramifying branches, is carefully carried out by the painter".[3] It is not obvious, however, that Cole would have been familiar with this concept, and critic Elwood C. Parry suggests that the likeness to any mythological tree is limited to the similarity of the goblet's stem to a tree trunk. There is nothing about the goblet analogous to branches or roots.[3]

The scale of the massive stone goblet contrasts with that of the traditional landscape scene around it, inviting comparisons with the large stone objects left by ancient races of giants in Greek mythology—a view endorsed by art historian Erwin Panofsky in the 1960s.[4] The painting's title (given by Cole on the back of the canvas) seems to support this idea, as if much time had passed between the creation of this goblet and the current scene. The setting sun, a romantic symbol, also evokes the passage of time.

The dominance of the goblet in the painting might suggest a cosmological interpretation. Parry considers but rejects a comparison with the exterior panels of Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1500), which are generally taken to depict the creation of Earth. Both images are of a contained world, but use water and terrain in differing proportions. Cole's Goblet offers neither iconography nor an inscription that would confirm a religious interpretation of the picture. Furthermore, the painter has placed the goblet far from the center of the canvas, which minimizes its emblematic significance.

The waters of the goblet, though, can be seen as a civilizing influence. The inhabitants of the goblet have a Utopian existence, pleasure boating on the tranquil waters and living among the temples and leafy woods. Where the waters spill onto the landscape below—where the two worlds interact—signs of life appear. In the background, far from the influence of the goblet's waters, the mountains are desolate and rocky. A similar depiction of civilization by the waterside can be seen in Cole's An Evening in Arcady (1843).

Louis Legrand Noble was a friend and biographer of Cole, and could have been expected to have some insight into the work. In his commentary, however, there is no mention of these ideas. He wrote, "There [the goblet] stands, rather reposes upon its shaft, a tower-like mossy structure, light as a bubble, and yet a section of a substantial globe. As the eye circles its wide rolling brim, a circumference of many miles, it finds itself in fairy land; in accordance though with nature on her broadest scale... Tourists might travel in the countries of this imperial ring, and trace their fancies on many a romantic page. Here steeped in the golden splendors of a summer sunset, is a little sea from Greece, or Holy Land, with Greek and Syrian life, Greek and Syrian nature looking out upon its quiet waters."[5]

Parry's 1971 article on the painting instead looks to Cole's first tour to Europe (1829–32) to unravel the imagery of the goblet. Cole visited England and its preeminent landscape painter, J. M. W. Turner, whose work he had mixed feelings about. He was however drawn to Turner's Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1829), making two sketches of the painting and another study for a possible treatment of his own, which did not come to fruition. The titular cyclops Polyphemus is pivotal to the ancient Greek epic The Odyssey, and Cole's interest in the subject demonstrates his openness to "the creative possibilities of such a Mediterranean scene".[6] Meanwhile, as Cole researched themes for his painting series The Course of Empire, he would have encountered the story of Mount Athos in Vitruvius's Ten Books on Architecture. The Ancient Roman writer recounts the suggestion of the architect Dinocrates to Alexander that the mountain be shaped into "the statue of a man holding a spacious city in his left hand, and in his right a huge cup, into which shall be collected all the streams of the mountain, which shall thence be poured into the sea."[7] This fantastical image appeared in 18th- and 19th-century illustrations that Cole may have seen. As Parry writes, "the precedent of a classical architectural fantasy on this scale supplies an alternative to the natural assumption that the Titan's goblet was actually made by a giant who simply left it behind".[8] But a literal rendition of this image may not have suited Cole's art: being a landscape artist, he would have been more comfortable expressing it only topographically, avoiding the need to render a massive stone human form.

Cole's drawings[9] from his trip to Europe or shortly thereafter also appear to prefigure the Goblet. They show his interest in fountains and basins and are influenced by those he saw during the Italian leg of his voyage, in Florence, Rome, and Tivoli. In one drawing, a series of huge basins adorned with vegetation descends to the sea. Another depicts a single, mossy-rimmed basin of normal size, but the ground-level view makes it appear monumental. Cole's drawings of the Italian volcanic lakes Nemi and Albano are also reminiscent of the goblet's waters and rim, insofar as they suggest that a "basic visual analogy was at work in Cole's thoughts, an analogy between [these] actual landscapes he had observed and the shape of the water vessels and basins he imagined."[10]

Parry also suggests the "unusual, but not impossible" idea that Cole's Goblet was a landscape artist's answer to the still life genre. Visiting the home of his patron Luman Reed, an avid art collector, Cole would have seen a still-life painting "with Goblet and Lemon" by the 17th-century Dutch artist Willem van Aelst. The highlight of that painting is a translucent glass goblet. The similarities are basic, with both paintings having a vertical format and an off-center drinking vessel.

Provenance

[edit]Cole likely painted the picture in a fairly short period, given its small size and very thin application of paint. (The canvas is very visible in the accompanying image, viewed at full resolution.) He did so without commission, so the subject was purely his own. He asked $100 for the work, apparently based on the size of the painting—his full-scale landscapes at the time fetched $250 to $500.

Cole sent The Titan's Goblet to Luman Reed, though it is not clear whether Reed owned it or simply reviewed it. The work was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1834 while owned by James J. Mapes. Artist John Mackie Falconer owned it by 1863. Samuel Putnam Avery donated the painting in 1904 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[11]

Recognized as a unique artwork, The Titan's Goblet was the only pre-20th-century American painting included at the Museum of Modern Art's "Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism" exhibition of 1936.[12]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Yggdrasil: The Sacred Ash Tree of Norse Mythology". The Public Domain Review.

- ^ The Titan's Goblet. Collections Database, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed August 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Parry, 126

- ^ Attributed to Panofsky in fn. 3, Parry, 123

- ^ Quoted with ellipsis in Parry, 126

- ^ Parry, 131

- ^ Quoted from Joseph Gwilt, translator, in Parry, 131

- ^ Parry, 133

- ^ Found in his sketchbooks at the Detroit Institute of Arts

- ^ Parry, 135

- ^ See the Metropolitan Museum of Art entry for provenance.

- ^ Parry, 123

References

[edit]- Parry, Elwood C., III (1971). "Thomas Cole's 'The Titan's Goblet': A Reinterpretation". Metropolitan Museum Journal. Vol. 4, pp. 123–40.