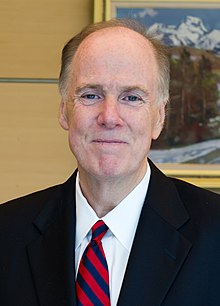

Thomas E. Donilon

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Thomas E. Donilon | |

|---|---|

| |

| 22nd United States National Security Advisor | |

| In office October 8, 2010 – June 30, 2013 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Deputy | Denis McDonough Tony Blinken |

| Preceded by | Jim Jones |

| Succeeded by | Susan Rice |

| 25th United States Deputy National Security Advisor | |

| In office January 20, 2009 – October 8, 2010 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | James Franklin Jeffrey |

| Succeeded by | Denis McDonough |

| 22nd Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs | |

| In office April 1, 1993 – November 7, 1996 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Margaret D. Tutwiler |

| Succeeded by | James Rubin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Edward Donilon May 14, 1955 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Cathy Russell |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Mike Donilon (brother) |

| Education | Catholic University (BA) University of Virginia (JD) |

Thomas Edward Donilon (born May 14, 1955) is an American lawyer, business executive, and former government official who served as the 22nd National Security Advisor in the Obama administration from 2010 to 2013.[1][2] Donilon also worked in the Carter and Clinton administrations. He is now Chairman of the BlackRock Investment Institute, the firm's global think tank.[3]

Originally from Providence, Rhode Island, Donilon spent his early career in Democratic politics and then in foreign policy and national security. He has advised the presidential campaigns of Jimmy Carter, Walter Mondale, Joe Biden, Michael Dukakis, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton, designing policy, managing conventions, preparing candidates for debates, and overseeing presidential transitions. In 1992, Donilon was named chief of staff and assistant secretary of state at the State Department. During his tenure in the Clinton administration, Donilon played a leading role in NATO's enlargement and the Dayton Agreement, and conducted diplomacy in more than 50 countries.

During the Obama transition, Donilon served with diplomat Wendy Sherman as Agency Review Team Lead for the State Department.[4] Upon Obama's inauguration he joined the administration as Deputy National Security Advisor, and was appointed National Security Advisor on October 8, 2010.[5] Donilon tendered his resignation as National Security Adviser on June 5, 2013, and was succeeded in office by Susan Rice.[6]

Since leaving government, Donilon has served in an advisory role as chair of the Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity, appointed by Obama;[7] and as vice chairman of the international law firm O'Melveny & Myers. During Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign, Donilon was co-chair of the Clinton-Kaine Transition Project and its foreign policy lead.[8] In 2020, Joe Biden reportedly offered Donilon the position of Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. [9]

Early life and education

[edit]Donilon attended La Salle Academy, a Catholic school in Providence, Rhode Island.[10] In 1977, he earned a B.A. degree, summa cum laude, from The Catholic University of America, and received the President's Award, the highest honor.[11] In 1985, he received a J.D. degree at the University of Virginia, where he served on the editorial board of the Virginia Law Review.

Early career

[edit]Democratic politics

[edit]After graduating from Catholic University, Donilon began working in the Carter White House as a staffer in the Congressional Relations Office in 1977. At age 24, Donilon managed the 1980 Democratic Convention, at which Senator Ted Kennedy challenged President Carter for the nomination. A profile from 1980 described him as, "one of those Wunderkinder who spring out of nowhere to become driving forces in politics."[12] Carter defeated Kennedy's challenge for the nomination but lost the general election. In 1981, Donilon temporarily moved to Atlanta to assist the former president's transition to private life.[13] He served as a lecturer at his alma mater, Catholic University.[14]

In 1983, Donilon took a leave of absence from law school to work on Walter Mondale's presidential campaign, as the national campaign coordinator and convention director.[12] Donilon helped prepared Mondale for his presidential debates.[15] Donilon met his wife, Catherine Russell, on the Mondale campaign.[16] Both Russell and Donilon then worked on Joe Biden's 1988 presidential campaign. After Michael Dukakis won the Democratic nomination, Donilon prepared him for his debates.

During the George H. W. Bush administration, Donilon was recruited to the law firm O'Melveny & Myers by Warren Christopher, the firm's senior partner and the former Deputy Secretary of State under President Carter.

In 1992, Donilon led Bill Clinton's general election debate preparations and served as counsel to the transition directors.[17]

State Department chief of staff and assistant for public affairs

[edit]When Warren Christopher became Secretary of State under President Clinton, Donilon worked as his chief of staff and as Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs, from 1993 to 1996. In those posts, he traveled to more than 50 countries.[14] According to The Washington Post, in the Clinton administration, Donilon was "intimately involved in many major foreign policy issues, including negotiating the Bosnian peace agreement and the expansion of NATO."[18] During the Srebrenica massacre, Donilon advocated intervention and lobbied members of Congress and worked with allies to approve intervention.[16]

Private sector

[edit]Donilon worked as executive vice president for law and policy at Fannie Mae, the federally chartered mortgage finance company, as a registered lobbyist from 1999 through 2005.[18][19]

Before his appointment to the Obama Administration, Donilon had returned to the Washington office of the law firm O'Melveny & Myers, where he advised companies and their boards on a range of "sensitive governance, policy, legal and regulatory matters."[20] In addition, he "led the firm's successful effort to revitalize its pro bono commitment."[21]

Out of government, Donilon continued to participate in foreign policy, including as a member of the House and Senate Majority's National Security Advisory Group, under Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid.[22]

Obama administration

[edit]

In 2008, David Axelrod recruited Donilon to head Obama's presidential debate preparation team. After the election, Obama's pick for chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, recommended that James L. Jones, Obama's pick for National Security Advisor, hire Donilon as his deputy.[16] In October 2010, Donilon replaced Jones as National Security Advisor. According to The New Yorker, he took inspiration for the NSC process from former National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft.[23]

National Security Advisor (2010–2013)

[edit]As National Security Advisor, Donilon "oversaw the U.S. National Security Council staff, chaired the cabinet level National Security Principals Committee, provided the president's daily national security briefing, and was responsible for the coordination and integration of the administration's foreign policy, intelligence, and military efforts." Donilon also "oversaw the White House's international economics, cybersecurity, and international energy efforts" and "served as the President's personal emissary to a number of world leaders, including Chinese leaders Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping, President Vladimir Putin, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu."[3]

A profile in Foreign Policy magazine described "the extraordinarily tight leash [Donilon] holds over the foreign-policy apparatus, his demanding treatment of staff, and the way he allegedly undercuts or elbows aside challenges to his power."[24] Another profile, by Jason Horowitz in The Washington Post, defined the "Donilon Doctrine" as one that "envisions a re-balancing of resources and interests away from Afghanistan, the Middle East and Europe and toward Asia, where he sees America building bigger, better relationships with China and India."[25]

In June 2013, when Donilon announced he was leaving the White House, Obama said, "Tom's that rare combination of the strategic and the tactical. He has a strategic sense of where we need to go, and he has a tactical sense of how to get there."[6] Joe Biden said in a statement, "I've worked with eight different administrations and even more national security advisers, and I've never met anyone with more talent and with greater strategic judgment."[6]

David Rothkopf wrote of Donilon's legacy:

"Donilon's greatest contribution was his strategic mindset, leading to a conscious shift away from the issues that preoccupied the NSC under George W. Bush in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the broader post-9/11 "Global War on Terror" to one that centered on next generation issues: China, cyber issues, the strategic consequences of America's energy revolution, introducing new economic initiatives in the Atlantic and Pacific that have broad geopolitical consequences, moving to a next generation Mideast strategy focused on regional stability, along with new partnerships with regional and global players and addressing emerging threats in places like Africa."[26]

Asia

[edit]

Donilon was a prominent advocate of the Obama administration's "pivot" or rebalance to Asia.[27] Donilon described the policy in a speech at the Asia Society in 2013: "The United States is implementing a comprehensive, multidimensional strategy: strengthening alliances; deepening partnerships with emerging powers; building a stable, productive, and constructive relationship with China; empowering regional institutions; and helping to build a regional economic architecture that can sustain shared prosperity."[28]

In July 2012, Donilon met with then Chinese leader Hu Jintao and Dai Bingguo. The next year, he traveled to China again and met with Xi Jinping; during his visit, Donilon called for a "healthy, stable, and reliable military-to-military relationship" between the United States and China.[29]

Donilon was also critical of China at times. He was the first American official to publicly admonish China for its cyber espionage.[30] In 2013, in a speech to the Asia Society, Donilon said "Increasingly, U.S. businesses are speaking out about their serious concerns about sophisticated, targeted theft of confidential business information and proprietary technologies through cyber-intrusions on an unprecedented scale." Donilon said China must recognize the risk such activities pose to the reputation of Chinese industry, to bilateral relations, and to international trade. Beijing, he said, must also "take serious steps to investigate" allegations of hacking.[31]

Before leaving the Obama Administration, Donilon coordinated a two-day informal summit between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Obama held in Sunnylands, California, in June 2013.[32]

International economics

[edit]

Donilon supported the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which he called "the most important trade negotiation under way in the world today and the economic centerpiece of the rebalance" to Asia.[33] At the same time, he advocated the importance of building trade ties between trans-Atlantic allies, through the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP).[33]

Human rights

[edit]Ahead of President Obama's trip to Myanmar, Donilon called on the Philippines and Myanmar to uphold human rights amid their democratic transitions.[34]

Obama charged Donilon with setting up the interagency standing Atrocities Prevention Board, which would define mass atrocity prevention as a "core national security interest and a core moral responsibility in the United States of America."[35]

Russia

[edit]Donilon helped negotiate the New START treaty in 2011.[36] He traveled to Moscow for an hours-long discussion with Russian President Vladimir Putin shortly after his election in 2012.[37] Donilon told Putin that Russia should "help ease [Bashar] al-Assad out and let a democratic government take his place because otherwise an extended civil war would open the door to the very radicalism [Putin] feared."[38]

Middle East

[edit]Donilon developed a strong relationship with the Israeli government, traveling for a five-hour meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 2012 without visiting any other countries in the region—a first for a national security advisor, according to diplomat Dennis Ross. As Ross wrote of Donilon's tenure, "It was not that [Donilon] agreed with everything he heard or in any way held back in conveying what was important to President Obama—quite the contrary. Rather, he gave Netanyahu the sense that Israel got a 'fair hearing' and his views were taken into account when U.S. actions were considered."[39] Robert D. Blackwill and Philip H. Gordon echoed the sentiment in a report for the Council on Foreign Relations, writing that the U.S.-Israel Consultative Group, a channel for national security dialogue between the two countries, "functioned effectively at times during the Obama administration, particularly from 2010 to 2013 under national security advisers Thomas Donilon in the United States and Yaakov Amidror in Israel."[40]

In preparation to advise the President on Afghanistan and Pakistan, Donilon commissioned evaluations of the decision-making processes underpinning both the Vietnam War and the Iraq War, which showed, according to Newsweek, "an astonishing historical truth: neither the Vietnam War nor the Iraq War featured any key meetings where all the issues and assumptions were discussed by policymakers. In both cases the United States was sucked into war inch by inch."[41] Donilon was opposed to further intervention in Afghanistan. He worked with Vice President Biden to manage the withdrawal of troops from Iraq by the end of 2011.

During debates within the Obama administration over military intervention in Libya in 2011, Donilon "urge[d] caution in Libya", according to former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates' 2014 memoir, alongside Joe Biden, William M. Daley, Michael Mullen, Dennis McDonough, and John Brennan, while Samantha Power, Susan Rice and Ben Rhodes advocated action. Donilon recommended Obama conduct the Osama Bin Laden raid in May 2011, and was part of a small group planning the raid in the preceding months.[42]

In 2011, Donilon gave a speech to the Brookings Institution about the Obama administration's pressure campaign in response to Iran's nuclear program. "If Tehran does not change course, the pressure will continue to grow," Donilon said. That pressure, he said, would include increasing sanctions and shoring up defense of Iran's neighbors. "Iranians," he said, "deserve a government that puts their daily ambitions ahead of its nuclear ambitions."[43] Donilon headed the White House team that worked with State Department officials—Hillary Clinton, secretary of state; William J. Burns, deputy secretary of state; and Jake Sullivan, director of policy planning—to negotiate a backchannel, through Oman, with Iran on its nuclear project.[44]

Post-Obama administration

[edit]After leaving government in 2013, Donilon joined the Council on Foreign Relations as a distinguished fellow. At the Council on Foreign Relations, Donilon co-chaired, along with former Governor of Indiana Mitch Daniels, the organization's first task force on global health. The task force issued its report, "The Emerging Global Health Crisis Noncommunicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries," in December 2014.[45] The same year, Donilon delivered the Landon Lecture at Kansas State University, in which he rejected the notion of American decline. In it, he argued, "No nation can match our comprehensive, multidimensional set of enduring strengths: bountiful resources—both human and material, our global network of alliances, our unmatched military strength, our entrepreneurship and innovation, our liberal political and economic traditions, and our remarkable capacity for self-assessment and rejuvenation." Donilon also outlined challenges for the United States and recommended that the government reduce the budget deficit, improve infrastructure, invest in science research, pass immigration reform that gives a path to citizenship, and invest in primary and secondary education.

Donilon returned to O'Melveny & Myers in 2014 as vice chair of the firm and a member of the firm's global policy committee. Since April 2017, Donilon has been chairman of the BlackRock Investment Institute, the firm's internal think tank.

In April 2016, Obama appointed Donilon as chair of the Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity. The commission's report, which was released in December of that year, made recommendations for enhancing cybersecurity in the United States. Donilon presented the findings to Obama, who called them "thoughtful and pragmatic" and asked for them to be presented to President-elect Donald Trump's transition team.[46] Ahead of the 2016 presidential election, after the Democratic National Committee cyber attacks, Donilon called for an FBI investigation of the attack and public condemnation against the perpetrators, saying that Russia's claims that it does not interfere in political processes in cyberspace were "just wrong."[47] In 2017, Donilon wrote an opinion piece in The Washington Post in which he provided recommendations for "hack-proofing" future elections from foreign meddling.[48]

During Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, Donilon was co-chair of the Clinton-Kaine Transition Project, as its foreign-policy lead.[8] If Clinton had won, Donilon was widely considered a candidate to be Secretary of State[49] or CIA Director.[50]

Donilon has continued to comment on foreign policy and was publicly critical of the Trump administration. In January 2017, after Trump signed the "Muslim ban," Donilon joined an amicus brief which argued there was "no meaningful evidentiary support for the claimed national security imperative underlying" Trump's executive order.[51] In 2018, he condemned Trump's decision to pull out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action as "the worst mistake the United States has made in the Middle East since the Iraq War."[52] In 2019, in an article for Foreign Affairs, he criticized the Trump administration's trade war with China, and instead called for a broader strategy rooted in reinvesting in American science, education, infrastructure, alliances, and talent, including through welcoming immigration.[53]

In 2020, Biden reportedly offered Donilon the position of Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, though Donilon "decided against taking the job" according to the New York Times.[54]

Donilon is a member of the Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee.[55]

Personal life

[edit]

Donilon is the brother of Mike Donilon, a lawyer and political consultant who was senior advisor to President Joe Biden from January 2021 to January 2024. His other brother, Terrence Donilon, is the communications director for the Archdiocese of Boston.[56] Donilon's sister, Donna, is a nurse. He is married to Catherine M. Russell, who was chief of staff to Jill Biden, and in March 2013 was named the Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women's Issues at the U.S. State Department. They have two children.[57][58]

Honors and awards

[edit]| Award | Organization |

|---|---|

| Secretary of State's Distinguished Service Award | Department of State[59] |

| National Intelligence Distinguished Public Service Medal | United States Intelligence Community[59] |

| Department of Defense Medal for Distinguished Public Service | Department of Defense[59] |

| Joint Distinguished Civilian Service Award | Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff[59] |

| Director's Award | Central Intelligence Agency[59] |

| Government of Japan[60] |

References

[edit]- ^ Sanger, David E. (October 8, 2010). "Donilon to Replace Jones as National Security Adviser". The Caucus. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ The Washington Post Washington Post

- ^ a b "Thomas Donilon: Biography". BlackRock.

- ^ "Obama-Biden Transition: Agency Review Teams | Change.gov: The Obama-Biden Transition Team". Change.gov. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Defense Secretary Said to Be Staying On Baker, Peter. The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Landler, Mark (June 5, 2013). "Rice to Replace Donilon in the Top National Security Post". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Rockwell, Mark (November 21, 2016). "Cyber panel closes in on final recommendations -". FCW.

- ^ a b Allen, Cooper. "Clinton-Kaine transition team announced". USA Today. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/09/us/politics/william-burns-cia-biden.html

- ^ "La Salle Graduate Named National Security Advisor". LaSalle Academy. October 8, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ "Thomas Donilon". LawTally. April 6, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Don of the Delegates". Washington Post. August 12, 1980.

- ^ Morrell, Michael (October 3, 2017). "Former National Security Advisor Tom Donilon looks back on his Career". The Cipher Brief (Podcast). The Cipher Brief. Event occurs at 09:20. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "AllGov - Officials". www.allgov.com. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "5 Things You May Not Know About Tom Donilon". The Aspen Institute. January 6, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Tom Donilon: Political wunderkind to policy trailblazer". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ McGrory, Mary (October 20, 1992). "'No Surprises' School of Debate". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "Post Politics: Breaking Politics News, Political Analysis & More – The Washington Post". Whorunsgov.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ "Duo Heading State Transition Seasoned Vets". USA Today. November 12, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "O'Melveny & Myers LLP | Professionals". O'Melveny & Myers. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ "Thomas Donilon - O'Melveny". www.omm.com. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Pelosi, Reid, Former Defense Secretary Perry Announce New Review of Post-9/11 National Security Record". Speaker Nancy Pelosi. March 28, 2007. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Lizza, Ryan (April 25, 2011). "The Consequentialist". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Mann, James (September 5, 2024). "Obama's Gray Man". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (December 21, 2010). "Is the Donilon Doctrine the new New World Order?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Rothkopf, David (June 5, 2013). "Donilon's Legacy". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Rogin, Josh (March 11, 2013). "Donilon defends the Asia 'pivot'". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Remarks By Tom Donilon, National Security Advisor to the President: "The United States and the Asia-Pacific in 2013" - The Asia Society

- ^ "US national security adviser Tom Donilon promotes military ties in Beijing". South China Morning Post. May 28, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Landler, Mark; Sanger, David E. (March 11, 2013). "U.S. Demands China Block Cyberattacks and Agree to Rules". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Nakashima, Ellen (March 12, 2013). "U.S. publicly calls on China to stop commercial cyber-espionage, theft of trade secrets". The Washington Post.

- ^ Rucker, Philip. "At U.S.-china shirt-sleeves summit, formalities and suspicions abound". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Donilon, Tom (April 15, 2013). "The President's Free-Trade Path to Prosperity". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "President Obama's Asia Policy and Upcoming Trip to the Region—Transcript of Conversation with Thomas Donilon" (PDF). CSIS. Center for Strategy and International Studies. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Obama Praised for Action Plan to Prevent Mass Atrocities, Genocide". Human Rights First. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Nuclear Agenda". The New York Times. February 23, 2013. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Putin opts out of G-8 summit, cancels meeting with Obama". Fox News. March 26, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Baker, Peter (September 2, 2013). "U.S.-Russian Ties Still Fall Short of 'Reset' Goal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Ross, Dennis (October 4, 2016). Doomed to Succeed: The U.S.-Israel Relationship from Truman to Obama. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-53644-2.

- ^ "Repairing the U.S.-Israel Relationship". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Alter, Jonathan (May 14, 2010). "Jonathan Alter: Obama, Year One, The Promise". Newsweek. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Gates, Robert (2015). Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War. p. 511.

- ^ Donilon, Tom (November 22, 2011). "Keynote Speech - Iran and Multilateral Pressure: An Assessment of Multilateral Effort to Impede Iran's Nuclear Program" (PDF). Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Clinton, Hillary (2014). Hard Choices. ISBN 978-1442367067.

- ^ "The Emerging Global Health Crisis". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Statement by the President on the Report of the Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity". whitehouse.gov. December 2, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Nelson, Louis (August 4, 2016). "Former Obama security adviser: U.S. should confront Russia with evidence of DNC hack". POLITICO. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Donilon, Thomas. "Russia will be back. Here's how to hack-proof the next election". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Viebeck, Elise. "Is Tom Donilon the front-runner to lead Clinton's State Department?". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Allen, Mike. "Axios QM: Ghosts in the Cabinet". Axios. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "Brief of Amici Curiae Former National Security Officials in Support of Respondents" (PDF).

- ^ Jennifer Hansler (June 11, 2018). "Obama national security adviser slams Trump's foreign policy moves". CNN. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Donilon, Tom (June 27, 2019). "Trump's Trade War Is the Wrong Way to Compete With China". Foreign Affairs: America and the World. ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/09/us/politics/william-burns-cia-biden.html

- ^ "Defense Policy Board". policy.defense.gov. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (March 10, 2013). "The brothers Donilon: One's boss is President Obama, the other's could be pope". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Obama, Biden relying on the Donilons of Providence - Projo Politics Blog". Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved November 29, 2008. Obama, Biden relying on the Donilons of Providence] Perry, Jack. Providence Journal ProJo Politics Blog. November 26, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ Biden Beefs Up Staff Rucker, Philip. November 26, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Thomas E. Donilon". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "令和4年秋の外国人叙勲 受章者名簿" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

External links

[edit]- O'Melveny & Myers

- National Security Council

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Thomas E. Donilon on Charlie Rose

- Thomas E. Donilon collected news and commentary at The New York Times