Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

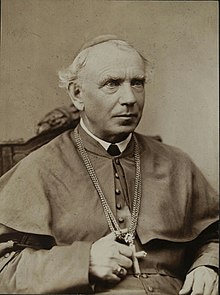

Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński | |

|---|---|

| |

| Archbishop and Confessor | |

| Born | 1 November 1822 |

| Died | 17 September 1895 (aged 72) Kraków |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 18 August 2002, Krakow, Poland by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | 11 October 2009, St. Peter's Basilica Rome by Pope Benedict XVI |

| Feast | 17 September |

Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński (1 November 1822 in Voiutyn, now Ukraine – 17 September 1895 in Kraków) was a professor of the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy, Archbishop of Warsaw in 1862-1883 (exiled by Tsar Alexander II to Yaroslavl for 20 years), and founder of the Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary. He was canonised on 11 October 2009 by Pope Benedict XVI.[1][2]

Early life

[edit]His parents were Gerard Feliński and Eva Wenderoff. He was born in Voiutyn (pol. Wojutyn) in Volhynia (present-day Ukraine) when it was part of the Russian empire. He was the third of six children, of whom two died at an early age.[3] His father died when he was eleven years old. Five years later in 1838 his mother was exiled to Siberia for a nationalist conspiracy (in which she tried to work to improve the social and economic conditions of the farmers), as a result he only got to see her again as a university student.

After completing high school, he studied mathematics at the University of Moscow from 1840 to 1844. In 1847 he went to Paris where he studied French literature at the Sorbonne and the Collège de France. In Paris he spent time living with Polish exiles, and knew Adam Mickiewicz and was a friend of Juliusz Słowacki.[3]

In 1848 he participated in the Polish uprising against Prussian rule in Poznań (then capital city of the semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen).[4]

From 1848 to 1850 he tutored the sons of Eliza and Zenon Brzozowski in Munich and Paris.[3]

Priesthood

[edit]

In 1851 he returned to Poland and entered the diocesan seminary of Zhytomyr. He studied at the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy. He was ordained on 8 September 1855 by the Archbishop of Mohilev, Ignacy Holowiński. He was assigned to the Dominican Fathers' parish of St Catherine of Siena in St Petersburg until 1857, when he was appointed as spiritual director of the Ecclesiastical Academy and a professor of philosophy. In 1856 he founded the charitable organization "Recovery for the poor". In 1857 he founded the Congregation of the Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary.

Appointment

[edit]He succeeded Antoni Melchior Fijałkowski to the Diocese of Warsaw in 1861. Archbishop Fijalkowski and the Polish hierarchy had emphasized the political obedience of Polish people to Russian rule (there had previously been the November Uprising against the Tsar in 1830 that the Pope had condemned in his encyclical Cum primum, in which he stressed the need to obey political rulers).

During the interim between Fijałkowski's death and Feliński's appointment, there had been growing patriotic unrest in Warsaw. Opposition leaders held protests within churches both on grounds of security (as it was presumed the police would not enter the church) and to calm conservative fears that they were not communists. Russia declared martial law in Poland on 14 October 1861, and the following day nationalists staged demonstrations inside Warsaw churches, two of which were broken up by Warsaw police (which led to further scandal, as the public could not accept Russian soldiers in Polish Catholic churches). The Cathedral Vicar ordered all Warsaw churches be closed in protest.[4]

On 6 January 1862, Feliński was appointed archbishop of Warsaw by Pope Pius IX, and he was consecrated in St Petersburg by Archbishop Zyliński. He left the Russian capital on 31 January and arrived in Warsaw on 9 February.

When Feliński was appointed archbishop, he was greeted with suspicion in Warsaw because he was approved by the Russian government. Feliński ordered the re-opening of Warsaw churches on 16 February (he also reconsecrated Warsaw Cathedral and had all churches opened with a solemn 40-hour exposition of the Blessed Sacrament), thus fulfilling the worst fears of the nationalists; he also banned the singing of patriotic hymns, and forbade the use of church buildings for political functions.[4]

The Polish underground press attacked him: an underground Catholic magazine called "The Voice of the Polish Chaplain" wrote about him:

under the scarlet robes and the mitre of Father Feliński hides one of those false prophets, against whom Christ told us to be on guard. . . . Every day brings us all sorts of new evidence that Father Feliński does not care for the country at all, that his heart is divided between Petersburg and Rome, and that he wants to make the clergy apathetic about the fate of the Fatherland, to turn it into an ultramontane caste that would have nothing in common with the nation."[4]

He defended himself as a Polish patriot and used the label "traitor" for anyone willing to surrender the dream of independence. He wrote:

The right of nations to independent existence is so holy and undoubted, and the inborn love of the fatherland is so deeply embedded in the heart of every true citizen, that no sophistry can erase these things from the mass of the nation.... All true Poles not only want to be free and independent in their own country, but all are convinced that they have an inaliable right to this, and they do not doubt that sooner or later they will stand before their desires and once again be an independent nation. Whoever does not demand independence or doubts the possibility of its attainment is not a Polish patriot.[4]

During his time as archbishop there were almost daily clashes between the Russian occupiers and the nationalists. The Russian government promoted the image of the archbishop as being their collaborator, thus sowing distrust among people toward him.[3]

In 1862, Pope Pius IX sent a letter to Feliński that criticized the existing civil laws in Russia as being opposed to the teachings, the rights and the freedoms of the Catholic Church, and he called on the archbishop to work for the freedom of those who had been imprisoned for the nationalist cause in Poland.[4] He made every effort to free the imprisoned priests. Feliński worked for the elimination of Russian government control of the Polish Catholic Church. He made regular visits to parishes and charitable organizations in the diocese, to better meet their needs. He reformed the programmes of study at the Ecclesiastical Academy of Warsaw and in diocesan seminaries, to give impetus to spiritual and intellectual development of the clergy. He encouraged priests to proclaim the gospel openly, to catechize their parishioners, to begin parochial schools and to take care that they raise a new virtuous generation.[3]

He looked after the poor and orphans, and started an orphanage in Warsaw that he put in the care of the Sisters of the Family of Mary.[3]

In January 1863 there was a major uprising in Poland against Russian rule that ended in failure, and was brutally repressed. Feliński protested against the repression by resigning from the Council of State. He protested against the hanging of Captain Fr. Agrypin Konarski.

In March 1863 Feliński wrote to Tsar Alexander II demanding that the Congress Kingdom of Poland be granted political autonomy and be restored to its pre-partition boundaries (including the territories that are now part of Lithuania, Belarus and the western Ukraine). The Tsar answered this letter by arresting Feliński and sending him into exile in the town of Yaroslavl on the Upper Volga (about 300 km to the NE of Moscow; where there were almost no Catholics). The Vatican supported Feliński's protest.[4]

Feliński nevertheless was opposed to the rebellion, as he later wrote in his memoirs:

In my opinion, the question of our behaviour in relation to the partitioning governments must not be resolved wholesale, but must be divided into at least three categories: the question of rights, the question of time, and the question of means. Regarding justice: neither Natural law, nor religion, nor international law, nor finally historical tradition forbids us from attaining with arms the independence that was taken from us by force. From a position of principle, then, no one can condemn us for rising up in arms, as something unjust by its very nature. The question of time and circumstances is only a question of prudence, and only from that perspective can it be resolved....The only area, then, in which it is permissible to judge the justice or injustice of an armed uprising aimed at regaining independence is the means of conducting the struggle, and in this regard our historians and publicists have not only the right, but the obligation to enlighten the national consciousness, so as to warn patriots against adventures that would be ruinous for the national soul.[4]

His concerns were especially reflected in other conservative Catholic voices that opposed the 1830 insurrection and 1863 rebellion on grounds of the left-wing political radicalism that many of the rebels were associated with, including atheistic ideologies. Feliński claimed revolution attacked both religion and the established social order. The social order of those times, extending into antiquity, was the Polish nobility and Polish clergy believed they were genetically superior to peasants.[5] Peasants were regarded as a lower species.[6]

He called on people to place their trust in the governance of Providence in world affairs:

Whoever manages to always see the finger of Providence in the course of historical events, and trusting in the justice of God, does not doubt that every nation will ultimately receive that which it has earned by its behavior, will recoil with disgust at the thought of committing a crime, even if that would be the only means of fighting an even greater injustice.[4]

Exile

[edit]He spent the next 20 years in exile in Yaroslavl. He was not allowed any contact with Warsaw.

During his exile he organized works of mercy to help his fellow prisoners (especially the priests among them), and collected enough funds (despite police restrictions) to construct a Catholic church that would become a new parish. The local people were struck by his spiritual attitudes and referred to him as the "holy Polish bishop".[3]

During his exile he wrote several works that he later published after his release. Included among them were: Spiritual Conferences, Faith and Atheism in the search for happiness, Conferences on Vocations, Under the guidance of Providence, Social Commitments in View of Christian Wisdom and Atheism, and Memories.[3]

Kraków

[edit]In 1883, following negotiations between the Holy See and Russia, he was released from exile and moved to Dzwiniaczka in southeastern Galicia (now Дзвинячка in Ukraine) among Ukrainian and Polish crop farmers. The Pope transferred him from Archbishop of Warsaw to Archbishop of the titular see of Tarsus. There he was chaplain of the manor house of Counts Keszycki and Koziebrodski, and he launched into intense pastoral activity. Out of his own money he built the first school and kindergarten in the village.[3] He also built a church and convent for the Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary.

He died in Kraków on 17 September 1895 and was buried on 20 September. On 10 October his body was moved to Dzwiniaczka, and his remains were removed again in 1920 to Warsaw, where on 14 April 1921 they were moved to the crypt of the Cathedral of Saint John, where they still are today.[3]

Views on Poland

[edit]Feliński criticized Zygmunt Krasiński's claim that Poland was a Christ among nations. Feliński said:

Although my nation was the victim of a cruel injustice," Feliński wrote, "it did not proceed to martyrdom either willingly or without sin, as did our Savior and the martyrs following in His footsteps. Considering our national guilt and mistakes, it would be more appropriate to call Poland, as it pays for its sins, the Mary Magdalene of nations, not the Christ of nations.[4]

In January 1863 he presented an interpretation of Poland's contemporary history as being a punishment from God for its sins:

The mission of Poland is to develop Catholic thinking in internal life... . Poland was great as long as these virtues lived within it, as long as there were no examples in its history of egoism or rapaciousness... When these national virtues fell, when decadence and egoism set in, then the flogging and the ruin arrived.[4]

This followed from the views of other Catholic conservatives at the time who believed that God would never grant Poland independence until it repented of its sins. Feliński believed that God would redeem Poland of its sins, and thereby give it independence, but he criticized the independence movement for failing to believe in the role of Providence and (in his view) thinking as though the governance of the world was entirely up to human will. In the view of contemporary Catholic conservatives, in whom Feliński had an important voice, the independence movement, whether it be based on the communist or liberal ideologies that had been adopted by many Polish nationalists, was doomed to failure because of this.

He believed that every nation had a special role given to it by God:

just as every member of the family has an assigned task corresponding to his or her natural abilities, so does every nation receive a mission in accordance with the features Providence deigned to grant it.[4]

From the fact that we lost independent existence, it does not at all follow that our mission has ended. The character of that mission is so spiritual, that not by the force of arms, but by the force of sacrifices will we accomplish that which love demands of us. If independence would become a condition necessary for fulfilling the task that has been laid upon us, then Providence itself would so manage the course of events that state existence would again be returned to us, so that we may sufficiently mature in spirit.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński bio from Patron Saint Index

- ^ "Eucharistic Celebration for the Canonization of Five New Saints". www.vatican.va. 11 October 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Zygmunt Szczęsny Feliński (1822-1895)". Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Brian Porter. Thy Kingdom Come: Patriotism, Prophecy, and the Catholic Hierarchy in Nineteenth-Century Poland. The Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 2 (Apr., 2003), pp. 213-239

- ^ Kuligowski, Waldemar Tadeusz (2 February 2017). "A History of Polish Serfdom. Theses and Antitheses" (PDF). czaskultury.pl. Poznań: Czas Kultury. p. 116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

To distance itself from the peasants, the nobility (and clergy) cultivated a belief in their genetic superiority over the peasants.

- ^ Kuligowski, Waldemar Tadeusz (2 February 2017). "A History of Polish Serfdom. Theses and Antitheses" (PDF). czaskultury.pl. Poznań: Czas Kultury. p. 118. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

Nobility does not enter, or does so very unwillingly, into marriages with serfs, regarding them as a lower species.