Andrew Hunter (lawyer)

Andrew H. Hunter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from the Jefferson County district | |

| In office December 7, 1846-December 3, 1848 | |

| Preceded by | William F. Turner |

| Succeeded by | Joseph F. McMurran |

| In office December 2, 1861-September 6, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | John T. Gibson |

| Succeeded by | Jacob S. Melvin |

| Member of the Virginia Senate from the Berkeley and Jefferson Counties district | |

| In office 1864-March 15, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Edwin L. Moore |

| Succeeded by | n/a |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 22, 1804 Martinsburg, West Virginia, (then Virginia) U.S. |

| Died | November 21, 1888 (aged 84) Charles Town, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Hampden-Sydney College |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

Andrew H. Hunter (March 22, 1804 – November 21, 1888) was a Virginia lawyer, slaveholder, and politician who served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, including the Confederate House of Delegates. He was the Commonwealth's attorney for Jefferson County, Virginia, who prosecuted John Brown for the raid on Harpers Ferry.

Early life

[edit]Hunter was born in 1804 to Col. David Hunter (1761–1829) and his wife, the former Elizabeth Pendleton (1774–1825) in Martinsburg, then in Berkeley County, Virginia, where his father long served as the county clerk. Although he had three brothers, one the Presbyterian clergyman Rev. Moses Hunter of New York,[1] the family had resources sufficient to pay for his education at Washington Academy, now Washington and Jefferson College, further along the National Road in Washington, Pennsylvania, then at Hampden-Sydney College, from which he graduated summa cum laude in 1822.[2] He married Elizabeth Ellen Stubblefield (d. 1873) and they had two sons, Henry Clay Hunter (1830-1886)—apparently named for the Kentucky politician Henry Clay—and Andrew Hunter Jr., and seven daughters.[3]

Hunter and slavery

[edit]Although he was not a pro-slavery spokesman—that honor belonged to his near-neighbor and author of the new Fugitive Slave Law, Senator James M. Mason—Hunter, like every Virginia politician, was firmly pro-slavery in any public context.

At the time of the 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Hunter owned five slaves: a 36 year old black male, black females aged 35 and 40, and a 6 year old mulatto boy.[4][full citation needed]

A Northern newspaper described Hunter as a "furious advocate of slavery".[5] He declared that the slave trade was "the source of great benefit, not only to the whites in those States, but particularly to the slaves themselves", and declared himself opposed to "sentimental legislation" that suppressed the foreign slave trade.[6] Nevertheless, another newspaper described him as "a warm friend of [abolitionist] Horace Greeley, strange as that may seem."[7]

Career

[edit]

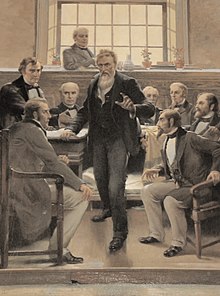

where 19th century Conventions met

Attorney, frequently for railroads

[edit]Hunter was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1828,[8] and practiced law in what became the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia in his lifetime. His elder brother became a prominent lawyer in Martinsburg, the Berkeley County seat, and Hunter began his practice in Harpers Ferry, then settled in Charles Town (Jefferson County's seat). Beginning in 1840, Andrew Hunter became one of the local attorneys for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), and for many years assisted it, first in acquiring the right of way to lay tracks in the county for the connection at Harper's Ferry, although beginning in 1844 Hunter was also a director of the Winchester & Potomac Railroad Company and represented them in their attempts to be taken over by the B&O as it tried to lay track to Wheeling (then in western Virginia).[9] Hunter was a presidential elector for the Whig party in 1840, but declined nomination for Congress.[2]

Virginia politician

[edit]Jefferson County voters elected Hunter as one of their (part-time) representatives in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1846, and he also worked for the B&O while in Richmond, but neither he nor his colleague William B. Thompson won re-election.[10][11]

In 1850, Jefferson County voters and those from neighboring Berkeley and Clarke Counties elected Hunter to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850, along with Charles J. Faulkner (another local B&O attorney), William Lucas, and Dennis Murphy.[12] Hunter and Lucas were "states' rights" men, although in the South Carolina nullification crisis of 1833, Hunter and Thompson had spoken strongly condemning South Carolina's course.[13]

Hunter was Virginia governor Henry A. Wise's personal attorney.[14]: 1688

It has been said that it was the John Brown affair that made Hunter a national figure,[8] but even before John Brown's raid, he was mentioned as a possible presidential candidate:

There is a quiet feeling in the delegation [to the 1860 Democratic National Convention], in favor of Mr Hunter. It is neither deep, enthusiastic, nor even well defined, or definitely fixed. It springs not so much from friendship for him, as from a latent conviction that the candidate upon whom the Convention will ultimately unite will be some considerate, moderate man like Hunter, to the exclusion of egoists and radicals like Wise, who expose themselves to the censure of the many by imprudent letters, or, like Douglas, who repel the necessary few by denunciatory speeches.[15]

The John Brown trial

[edit]

Charles Town, where Hunter lived, was only seven miles (11 km) from Harpers Ferry, where John Brown's 1859 raid produced a huge uproar, drawing national attention. By decision of Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, whose personal attorney Hunter was, Hunter was given the politically explosive task of prosecuting abolitionist John Brown and the others of his party who were captured; the county prosecutor, Charles B. Harding, by general agreement was not capable of handling such a high-profile case, and he was happy to be "assisted". Thus, Hunter, who signed himself "Assistant Prosecuting Attorney",[17] quickly drafted the indictment and prosecuted John Brown and his associates for murder, inciting a negro insurrection, and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. "Mr. Hunter had against him some of the finest legal talent of the North. He conducted the trial with great ability and made a national reputation as a lawyer."[18] The defendants were convicted of all charges, except that since according to the Dred Scott decision Blacks were not citizens, the two Black defendants, Shields Green and John Anthony Copeland, could not commit treason, so that charge was dropped for those two defendants. All were sentenced to death and all were executed by hanging.[19]

The circuit judge and the out-of-town attorneys having left, it was Hunter who was in charge of everything local relating to Brown during his final month. He was "the first man in Charlestown".[20] Only he could have written the "Proclamation" of November 28, announcing the arrest of those in Jefferson County who could not explain their business there.[17] It was Hunter who opened and read every letter addressed to Brown, retaining 70 to 80 that "he could not get, never would get, as I thought they were improper"; they were shipped to Richmond along with the other documents. Hunter told the jailor Captain Avis to treat Brown well.[21][7][22]

Hunter was already "the recognized leader of the bar of this [Jefferson] county".[8] The John Brown trials gave him a national reputation.[8] He was at that time "one of the leading attorneys of the United States".[23]

In 1881 Hunter went to Storer College to hear Frederick Douglass talk on Brown, and congratulated him when he was done.[24][25] A visitor in 1883 wrote that "it seems to renew the youth of this venerable octogenarian to talk of John Brown". According to Hunter, Brown "was the bravest man I ever saw."[26]

Confederate politician

[edit]Hunter was, during the war, "the trusted friend and advisor of General Robert E. Lee".[8][2]

After Virginia voted for secession and the American Civil War began, Hunter and fellow lawyer Thomas C. Green (Charles Town's mayor, a Confederate tax assessor and later a justice of the West Virginia Supreme Court)[27] represented Jefferson County under the Confederate regime in the Virginia House of Delegates during the sessions of 1861/62 and 1862/63, but neither won re-election in 1863.[28] Another local B&O attorney, Thomas Jefferson McKaig (the railroad's counsel in Cumberland, Maryland, for nearly four decades and who served in both houses of the Maryland legislature), would also side with the Confederacy.[29] After the resignation of banker and Confederate officer Edwin L. Moore (of the 2nd Virginia Infantry, in which his lawyer son Henry Clay Hunter fought as a private before receiving a lieutenant's commission in July 1861),[30] Hunter then became State Senator for his district, by then occupied by Federal troops (and the U.S. Congress having recognized West Virginia as the 35th State).[31][11] His youngest brother, Rev. Moses Hoge Hunter (1814-1899), served as chaplain of the 3rd Pennsylvania cavalry during that war, and would later edit the memoirs of their cousin, Union General David Hunter (particularly despised by Confederate sympathizers in western Virginia because of his raids, including that which destroyed the pro-Confederate Virginia Military Institute). General Hunter in July 1864 ordered subordinates to burn Andrew Hunter's home, and Hunter was then imprisoned for a month without explanation nor charges.[32]

Law practice

[edit]After the war, Hunter resumed his legal practice. As the county's leading attorney, he again often opposed Charles J. Faulkner in court. Beginning in 1865, when West Virginia legislators moved the Jefferson County seat from Charles Town to Shepherdstown. Hunter fought to move the county seat back, and successfully defended a later law moving the county seat back to Charles Town (from Shepherdstown); Faulkner represented the losing Shepherdstown side.[33] Hunter was later one of the losing attorneys representing Virginia in Virginia v. West Virginia, Virginia's suit to take back the counties of Jefferson and Berkeley, which the U.S. Supreme Court decided in 1871 (Faulkner was on the winning side).[34]

Death

[edit]Andrew Hunter died at his home in Charles Town, Jefferson County, West Virginia, on November 21, 1888. He was in good health until shortly before his death (attributed in an obituary to "old age").[35] He is buried with other family members in the cemetery of Zion Episcopal Church in Charles Town.[3] He was survived by two daughters,[8] Mary E. Kent and Florence Hunter.[36] His son Andrew Hunter, Jr., died "in Confederate service"; his other son, Henry Clay Hunter, an attorney, died a year before his father.[8] His nephew Robert W. Hunter, also a Confederate officer and delegate, would survive the war and become the Secretary of Virginia Military Records.

Writing

[edit]- Hunter, Andrew (1897). "John Brown's Raid". Southern History Association. 1 (3): 165–195. Earlier newspaper versions of these recollections: 1887,[7] more legible reprint of same story,[22] 1888.[37]

References

[edit]- ^ "Andrew Hunter. A Talk with the Man who Prosecuted the Liberators.—The Story of the Hidden Carpet-Bag". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. St. Louis, Missouri. April 8, 1888. p. 27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Pulliam 1901, p. 107

- ^ a b findagrave no. 18189914[unreliable source?]

- ^ 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Jefferson County, Virginia pp. 37 and 38 of 44

- ^ "Those that fought with John Brown at Harper's Ferry". Indianapolis Recorder. February 27, 1937. p. 9.

- ^ Wilson, Henry (1872). History of the rise and fall of the slave power in America. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. p. 296.

- ^ a b c Hunter, Andrew (September 5, 1887). "John Brown's Raid. Recollections of Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter. The Capture, Trial, and Execution of Brown and His Party—Operations of His Emissaries—The Leader's Firmness and Coolness—Incidents of the Trial and Execution—Preparations to Prevent a Rescue". The Times-Democrat. New Orleans, Louisiana. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Death of a Prominent Man". Shepherdstown Register. Shepherdstown, West Virginia. November 30, 1888. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ James D. Dilts, The Great Road: the Building of the Baltimore & Ohio, the Nation's First Railroad, 1828-1853 (Stanford University Press 1993) p. 260

- ^ Cynthia Miller Leonard (ed), The General Assembly of Virginia 1619-1978: A Bicentennial Register of Members (Richmond, 1978) pp. 422

- ^ a b Swem 1918, p. 390

- ^ Leonard 1978, p. 441

- ^ Bushong 1941, pp. 114, 144

- ^ Lubet, Steven (June 1, 2013). "Execution in Virginia, 1859: The Trials of Green and Copeland". North Carolina Law Review. 91 (5): 1785–1815, at page 1789. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "New-York at Charleston". New-York Tribune. October 3, 1859. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Essex County, New York, Courthouse History, retrieved July 22, 2021

- ^ a b "Affairs at Charlestown—Old Soldiers—Preparations for the Execution—The Railway Discipline—A Letter from a Bereaved Mother". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). December 1, 1859. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "A Prominent Man Gone". Wheeling Register. Wheeling, West Virginia. November 24, 1888. p. 3 – via VirginiaChronicle.

- ^ Bushong 1941, pp. 190-202

- ^ "John Brown's Invasion. Personal Portraits". New-York Tribune. November 17, 1859. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter, Andrew (1897). "John Brown's Raid". Southern History Association. 1 (3): 165–195.

- ^ a b Hunter, Andrew (September 18, 1887). "John Brown's Raid. Interesting Reminiscences Written by the Lawyer Who Prosecuted Him.—Incidents of His Trial—His Conviction, Sentence and Execution.—His Purposes as He Declared Them.—The Effect of the Raid on Southern Sentiment". St. Joseph Gazette-Herald. St. Joseph, Missouri. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Latest news items". Shenango Valley News. Greenville, Pennsylvania. November 30, 1888. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1881). John Brown. An address by Frederick Douglass, at the fourteenth anniversary of Storer College, Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, May 30, 1881. Dover, New Hampshire. pp. 3–4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Revenges of Time". New England Farmer. Boston. June 4, 1881. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Northrop, B. G. (July 4, 1883). "As Others See Us.—A High Complement to West Virginia's Improvement.—Some incidents of early days.—A Prominent New Yorker Visits Our State and is Surprised at Its Progression and the Thriftiness of Its Inhabitants". Daily Register. Wheeling, West Virginia. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com. Also available at VirginiaChronicle

- ^ Dennis E. Frye, 2nd Virginia Infantry (3d ed. H.E. Howard Inc. 1984) p.101

- ^ Leonard 1978, p. 479

- ^ Dilts p. 260

- ^ Frye p.108

- ^ Leonard 1978, p. 487n

- ^ Bushong 1941, pp. 230-231

- ^ Bushong 1941, p.276-277

- ^ Bushong 1941, pp. 277-279, 293-294

- ^ "A prominent man gone. Death of Hon. Andrew Hunter, of Charlestown". Wheeling Register. Wheeling, West Virginia. November 24, 1888. p. 3 – via VirginiaChronicle.

- ^ Keys, Jane Griffith (November 18, 1906). "Virginia Heraldry...Hunters, Past and Present". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter, Andrew (November 6, 1888). "Tragedy. Reminiscences of the Virginia Attorney who Prosecuted at the Trial". The Journal. Meriden, Connecticut. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bushong, Millard Kessler (1941). A History of Jefferson County, West Virginia, 1719–1940. Heritage Books. ISBN 9780788422508.

- Pulliam, David Loyd (1901). The Constitutional Conventions of Virginia from the foundation of the Commonwealth to the present time. John T. West, Richmond. ISBN 978-1-2879-2059-5.

- Swem, Earl Greg (1918). A Register of the General Assembly of Virginia, 1776-1918, and of the Constitutional Conventions. David Bottom, Superintendent of Public Printing. ISBN 978-1-3714-6242-0.

Further reading

[edit]- "Hon. Andrew Hunter". Staunton Spectator (Staunton, Virginia). November 29, 1859. p. 1.