"Pliosaurus" andrewsi

| "Pliosaurus" andrewsi Temporal range: Middle Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Four-sided view of one of the teeth from the holotype of "P." andrewsi (NHMUK PV R3891). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Pliosauridae |

| Clade: | †Thalassophonea |

| Genus: | †"Pliosaurus" |

| Species: | †"P." andrewsi |

| Binomial name | |

| †"Pliosaurus" andrewsi | |

"Pliosaurus" andrewsi is an extinct species of pliosaurid plesiosaurs that lived during the Callovian stage of the Middle Jurassic, in what is now England. The only known fossils of this taxon were discovered in the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation. Other attributed specimens have been discovered in various corners of Eurasia, but these are currently seen as indeterminate or coming from other taxa. The taxonomic history of this animal is quite complex, because several of its fossils were attributed to different genera of pliosaurids, before being concretely named and described in 1960 by Lambert Beverly Tarlo as a species of Pliosaurus. However, although the taxon was found to be valid, subsequent revisions found that it is not part of this genus, and therefore a taxonomic revision must be carried out on this species.

"P." andrewsi has a skull that would have had an elongated snout capable of catching agile prey. Its teeth are round in cross section, with some longitudinal ridges on them. Unlike Pliosaurus, "P." andrewsi is among the most basal representatives of the Thalassophonea, a group of pliosaurids characterized by a short neck. "P." andrewsi would have inhabited an epicontinental (inland) sea that was around 30–50 metres (100–160 ft) deep. It shared its habitat with a variety of other animals, including invertebrates, fish, thalattosuchians, ichthyosaurs, and other plesiosaurs. At least five other pliosaurids are known from the Peterborough Member, but they were quite varied in anatomy, indicating that they would have eaten different food sources, thereby avoiding competition.

Research history

[edit]Discovery and identification

[edit]

The first possible mention of "Pliosaurus" andrewsi in scientific literature dates back to 1871, in which John Phillips catalogued pliosaur fossils having been discovered by Charles Leeds in the Oxford Clay Formation, England.[2]: 316–318 This formation, well known because of its significant preservation of plesiosaurians, is dated to the Callovian stage of the Middle Jurassic,[3][4] a period ranging from 166 to 164 million years.[1] The specimen, consisting of a swimming paddle and a mandible which are rather well preserved, was assigned the scientific name of Pleiosaurus? grandis in Phillips' review.[2]: 317–318 The specimen consists of an elongated mandibular symphysis possessing 11 pairs of teeth, of which the fifth and sixth anterior ones are caniniform. Based on these descriptions, Richard Lydekker referred the specimen to the newly named Peloneustes philarchus in 1889.[5]: 49–50 [6]: 163 The following year, Lydekker assigned the mandible to the proposed species Peloneustes evansi, due to its larger size than specimens attributed to Peloneustes philarchus. When Lambert Beverly Tarlo officially described "Pliosaurus" andrewsi in 1960, the mandible was attributed to this new species name.[6]: 163–164 However, in the official 2022 description of Eardasaurus, another pliosaurid from the Oxford Clay Formation, Phillips's mandible (cataloged as NHMUK R2443) is considered as a specimen of undetermined affinities and cannot be clearly attributed to "P." andrewsi.[4]

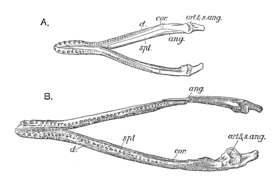

In 1913, Charles William Andrews attributed a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to Peloneustes evansi, noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other specimens of that species, they remain quite different from those of Peloneustes philarchus. Therefore, Andrews considered it possible that Peloneustes evansi belonged to a distinct genus that would have been morphologically intermediate between Peloneustes and Pliosaurus.[7]: 72 In 1958, Tarlo considered the larger remains attributed to Peloneustes evansi to belong to a new species of Pliosaurus, determining them to be very different from Peloneustes, just as Andrews previously suggested.[8]: 439–441 Two years later, in 1960, he named the taxon Pliosaurus andrewsi and designated the partial skeleton (cataloged as NHMUK R3891) as the holotype of this species.[6]: 163–164 The holotype specimen is a skeleton consisting of a mandible, teeth, a complete vertebral column as well as parts of the fore and hind limbs.[7]: 72 [6]: 164 [9][3] Tarlo also gave an anatomical description showing the main differences with other pliosaurs of the Oxford Clay Formation.[6]: 163–164 The specific epithet andrewsi is named in honor of Andrews,[10] who was the first to propose that the fossil remains of this taxon belong to a different genus from Peloneustes.[7]: 72

The taxonomic identity of this species remained undisputed for decades,[11][12] but in the early 2010s phylogenetic and anatomical revisions showed that it did not belong to the genus Pliosaurus.[13] After this discovery, the taxon was renamed as "Pliosaurus" andrewsi in studies published since, the quotation marks indicating its non-belonging within this genus.[14][9]

Formerly attributed specimens

[edit]- In Tarlo's 1960 description, he attributed some teeth of the chinese pliosaurid Sinopliosaurus weiyuanensis to P. andrewsi, seeing them as conspecific to the latter.[6]: 163–164 This attribution nevertheless remains doubtful, because Sinopliosaurus is a nomen dubium.[15]

- Still in his 1960 description, Tarlo refers all fossil material of the disputed species "Pliosaurus" grossouvrei to "P." andrewsi.[6]: 163–164 The holotype of "P." grossouvrei comes from the French commune of Charly, while the other fossils referred to come from different localities in England. In 2018, David Foffa and his colleagues showed that fossils of "P." grossouvrei show enough differences to not be seen as a synonym of "P." andrewsi, therefore being distinguished from this latter.[3]

- In 1972, paleontologist Teresa Maryańska referred another specimen of Oxfordian of the Late Jurassic to "P." andrewsi on the basis of teeth and cranial fragments, discovered in Częstochowa, Mirów, Poland.[16] Major parts of this specimen, later cataloged as M.Cz. V1293, were lost during the 1990s, the only part of it still intact being a small fragment of the jaw. Madzia and her colleagues suggested in 2021 that the specimen is an indeterminate thalassophonean.[17]: 102, 121

Description

[edit]The mandible of "P." andrewsi has a mandibular symphysis which contains up to 12 pairs of teeth,[9][18] of which the seventh pair is broad and caniniform.[6]: 164 The total number of teeth in each ramus would have been approximately 32,[6]: 164 indicating a total number of 64 teeth in the mandible.[9] The mandible in general is quite similar to that of Pliosaurus brachydeirus.[6]: 164 Based on this morphology, "P." andrewsi would have had an elongated snout capable of catching small, agile prey.[11] The main distinguishing feature of "P." andrewsi is the morphology of its teeth. The teeth are round in cross section and the dental crown quite smooth, nevertheless having some longitudinal ridges. Unique case of dental wear among plesiosaurians, the crown has an abrasion which extends considerably further than any other known representatives of the group.[6]: 164 [9][3][4][18] The teeth of "P." andrewsi are suited for cutting, suggesting that it also attacked large prey.[12]

The articular surfaces of the cervical vertebrae have a circular outline with a narrow peripheral groove. Cervical ribs are double-headed,[6]: 164 a common feature among Jurassic pliosaurs. Characteristically, the cervical vertebrae lack ventral ridges and ventral surface ornamentation.[9] The neck length of the holotype specimen would have been approximately 78.3 cm according to David Martill and colleagues in 2023.[19]: 367 [a] Despite the fact that the vertebral column of "P." andrewsi is fully known, Tarlo did not analyze the caudal and dorsal vertebrae, because they do not have enough notable features to be described in detail. He also mentions that some isolated vertebrae assigned to "P." andrewsi are indistinguishable from those of its contemporary Simolestes vorax. The scapula is similar to that of P. brachydeirus, but is somewhat expanded distally.[b] The humerus is shorter and wider than the femur. The tibia, fibula and ulna are longer than they are wide, but in the radius, these proportions are reversed, being wider than long.[6]: 164

Classification

[edit]Since the first descriptions made on the fossils now referred to "Pliosaurus" andrewsi, they were classified in different genera of the Pliosauridae, a family to which the taxon has always been assigned since.[20][4] In 1960, Tarlo classified this species in the genus Pliosaurus due to the morphology of the mandible, which is very similar to that of the type species P. brachydeirus.[6]: 164 Subsequently, "P." andrewsi was historically recognized as a species of Pliosaurus until 2010, in which phylogenetic analyzes placed it outside of this genus.[13] Revisions conducted in 2012 on the genus Pliosaurus also confirm this placement, as the taxon has unique characteristics that distinguish it from other species in the genus. One of the main distinguishing features is the shape of its teeth, being conical, unlike all valid species of Pliosaurus, having trihedral shaped teeth.[14][9][18] Therefore, "P." andrewsi does not belong to Pliosaurus and needs a taxonomic revision, which is also confirmed by a similar study published in 2013.[21] The same year, Benson and Patrick S. Druckenmiller named a new clade within Pliosauridae, Thalassophonea. This clade included the "classic", short-necked pliosaurids while excluding the earlier, long-necked, more gracile forms.[22] In all analyses carried out since then, "P." andrewsi is among the most basal representatives of this clade, in a position generally located between Peloneustes and Simolestes, unlike Pliosaurus, which is among the most derived representatives.[21][4] Although its phylogenetic position allows it to be qualified as valid and distinct,[4] its taxonomy is unclear and needs a redescription.[14][9][3]

The following cladogram follows Ketchum and Benson, 2022.[4]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeoecology

[edit]Palaeoenvironment

[edit]

"P." andrewsi is known from the Peterborough Member (formerly known as the Lower Oxford Clay) of the Oxford Clay Formation.[20] While "P." andrewsi has been listed as coming from the Oxfordian stage (spanning from about 164 to 157 million years ago)[1] of the Upper Jurassic,[6] the Peterborough Member actually dates to the Callovian stage (spanning from about 166 to 164 million years ago)[1] of the Middle Jurassic.[20] The Peterborough Member spans from the late Lower Callovian to the early Upper Callovian, occupying the entirety of the Middle Callovian.[23] It overlays the Kellaways Formation[23] and is overlain by the Stewartby Member of the Oxford Clay Formation.[24] The Peterborough Member is primarily composed of grey bituminous (asphalt-containing)[23] shale and clay rich in organic matter.[25][26] These rocks are sometimes fissile (splittable into thin, flat slabs).[24] The member is about 16–25 metres (52–82 ft) thick, stretching from Dorset to Humber.[23]

The Peterborough Member represents an epicontinental sea during a time of rising sea levels.[26] When it was deposited, it would have been located at a latitude of 35°N.[24] This sea, known as the Oxford Clay sea, was largely encircled by islands and continents, which provided the seaway with sediment.[24] Its proximity to land is demonstrated by the preservation of terrestrial fossils such as driftwood in the Oxford Clay, in addition to a clastic dike in the lower levels of the Peterborough Member, with the dike's formation being facilitated by rainwater.[25] The southern region of the Oxford Clay Sea was connected to the Tethys Ocean, while it was connected to more boreal regions on its northern side. This allowed for faunal interchange to occur between the Tethyan and boreal regions. This sea was approximately 30–50 metres (100–160 ft) deep within 150 kilometres (93 mi) of the shoreline.[24][20]

The surrounding land would have had a Mediterranean climate, with dry summers and wet winters, though it was becoming increasingly arid. Based on information from δ18O isotopes in bivalves, the water temperature of the seabed of the Peterborough Member varied from 14–17 °C (57–63 °F) due to seasonal variation, with an average temperature of 15 °C (59 °F). Belemnite fossils provide similar results, giving a water temperature range with a minimum 11 °C (52 °F) to a maximum between 14 °C (57 °F) or 16 °C (61 °F), with an average temperature of 13 °C (55 °F).[24] While traces of green sulphur bacteria indicate euxinic water, with low oxygen and high hydrogen sulfide levels, abundant traces of benthic (bottom-dwelling) organisms suggest that the bottom waters were not anoxic.[27][26] Oxygen levels appear to have varied, with some deposits laid down in more aerated conditions than others.[24]

Contemporaneous biota

[edit]There are many kinds of invertebrates preserved in the Peterborough Member. Among these are cephalopods, which include ammonites, belemnites, and nautiloids. Bivalves are another abundant group, while gastropods and annelids are less so but still quite common. Arthropods are also present. Brachiopods and echinoderms are rare. Despite not being known from fossils, polychaetes probably would have been present in this ecosystem, due to their abundance in similar modern environments and burrows similar to ones produced by these worms. Microfossils pertaining to foraminiferans, coccolithophoroids, and dinoflagellates are abundant in the Peterborough Member.[11]

A wide variety of fish are known from the Peterborough Member. These include the chondrichthyans Asteracanthus, Brachymylus, Heterodontus (or Paracestracion),[11] Hybodus, Ischyodus, Palaeobrachaelurus, Pachymylus, Protospinax, Leptacanthus, Notidanus, Orectoloboides, Spathobathis, and Sphenodus. Actinopterygians were also present, represented by Aspidorhynchus, Asthenocormus, Caturus, Coccolepis, Heterostrophus, Hypsocormus, Leedsichthys, Lepidotes, Leptolepis, Mesturus, Osteorachis, Pachycormus, Pholidophorus, and Sauropsis.[28] These fish include surface-dwelling, midwater, and benthic varieties of various sizes, some of which could get quite large. They filled a variety of niches, including invertebrate eaters, piscivores, and, in the case of Leedsichthys, giant filter feeders.[11]

Plesiosaurs are common in the Peterborough Member, and besides pliosaurids, are represented by cryptoclidids, including Cryptoclidus, Muraenosaurus, Tricleidus, and Picrocleidus.[20] They were smaller plesiosaurs with thin teeth and long necks, and, unlike pliosaurids such as Peloneustes, would have mainly eaten small animals.[11] The ichthyosaur Ophthalmosaurus also inhabited the Oxford Clay Formation. Ophthalmosaurus was well adapted for deep diving, thanks to its streamlined, porpoise-like body and gigantic eyes, and probably fed on cephalopods.[11] Many genera of crocodilians are also known from the Peterborough Member. These include the gavial-like teleosauroids Charitomenosuchus, Lemmysuchus, Mycterosuchus, and Neosteneosaurus[29] and the mosasaur-like[11] metriorhynchids Gracilineustes, Suchodus, Thalattosuchus,[30] and Tyrannoneustes.[31] While uncommon, the small piscivorous pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus was also part of this marine ecosystem.[11]

More pliosaurid species are known from the Peterborough Member than any other assemblage.[20] Besides "P." andrewsi, these pliosaurids include Liopleurodon ferox, Simolestes vorax, Peloneustes philarchus, Marmornectes candrewi,[32] Eardasaurus powelli, and, potentially, Pachycostasaurus dawni.[33][4] However, there is considerable variation in the anatomy of these species, indicating that they fed on different prey, thereby avoiding competition (niche partitioning).[34]: 249–251 [35] The large, powerful pliosaurid Liopleurodon ferox appears to have been adapted to take on large prey, including other marine reptiles and large fish.[34]: 242–243, 249–251 The long-snouted Eardasaurus powelli like Liopleurodon also has teeth with cutting edges and may have also taken large prey.[4] Simolestes vorax, with its wide, deep skull and powerful bite, appears to have been a predator of large cephalopods.[34]: 243–244, 249–251 Peloneustes, like "P." andrewsi, possesses an elongated snout, an adaptation for feeding upon small, agile animals.[11] However, the teeth of Peloneustes are better adapted for piercing, while those of "P." andrewsi are suited to cutting, indicating a preference for larger prey.[12] "Pliosaurus" andrewsi is also larger than Peloneustes.[11] Marmornectes candrewi is also similar to Peloneustes, bearing a long snout, and perhaps also fed on fish.[22][32] Pachycostasaurus dawni is a small, heavily built pliosaur that probably fed on benthic prey. It has a weaker skull than other pliosaurids and was more stable, so it probably used different feeding methods to avoid competition.[35] Unlike the other pliosaurids of the Oxford Clay, Pachycostasaurus was rather rare, perhaps mainly living outside of the depositional area of the Oxford Clay Formation, possibly inhabiting coastal regions, deep water, or even rivers instead.[35] While several different types of pliosaurids were present in the Middle Jurassic, the long-snouted piscovorous forms such as "P." andrewsi died out at the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary. This seems to have been the first phase of a gradual decline in plesiosaur diversity. While the cause of this is uncertain, it may have been influenced by changing ocean chemistry, and, in later phases, falling sea levels.[22]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Cohen, K.M.; Finney, S.; Gibbard, P.L. (2015). "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy.

- ^ a b Phillips, J. (1871). Geology of Oxford and the valley of the Thames. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c d e Foffa, D.; Young, M. T.; Brusatte, S. L. (2018). "Filling the Corallian gap: New information on Late Jurassic marine reptile faunas from England". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 63 (2): 287–313. doi:10.4202/app.00455.2018. hdl:20.500.11820/729f4cac-6217-4a21-b22c-8683b38c733b. S2CID 52254345.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ketchum, H. F.; Benson, R. B. J. (2022). "A new pliosaurid from the Oxford Clay Formation of Oxfordshire, UK". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 67 (2): 297–315. doi:10.4202/app.00887.2021. ISSN 0567-7920. S2CID 249034986.

- ^ Lydekker, R. (1889). "On the remains and affinities of five genera of Mesozoic reptiles". The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 45 (1–4): 41–59. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1889.045.01-04.04. S2CID 128586645.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Tarlo, L. B. (1960). "A review of the Upper Jurassic pliosaurs". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 4 (5): 145–189.

- ^ a b c Andrews, C. W. (1913). A descriptive catalogue of the marine reptiles of the Oxford clay. Based on the Leeds Collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London. Vol. 2. London: British Museum.

- ^ Tarlo, L. B. (1958). "A review of pliosaurs". XVTH Internal. Cong. Zool. London. 9: 438–442.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Knutsen, E. M. (2012). "A taxonomic revision of the genus Pliosaurus (Owen, 1841a) Owen, 1841b" (PDF). Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92: 259–276.

- ^ Creisler, B. (2012). "Ben Creisler's Plesiosaur Pronunciation Guide". Oceans of Kansas. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Martill, D. M.; Taylor, M. A.; Duff, K. L.; Riding, J. B.; Bown, P. R. (1994). "The trophic structure of the biota of the Peterborough Member, Oxford Clay Formation (Jurassic), UK". Journal of the Geological Society. 151 (1): 173–194. Bibcode:1994JGSoc.151..173M. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.151.1.0173. S2CID 131200898.

- ^ a b c Massare, J. A. (1987). "Tooth morphology and prey preference of Mesozoic marine reptiles". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 7 (2): 121–137. Bibcode:1987JVPal...7..121M. doi:10.1080/02724634.1987.10011647.

- ^ a b Ketchum, H. F.; Benson, R. B. J. (2010). "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 361–392. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x. PMID 20002391. S2CID 12193439.

- ^ a b c Druckenmiller, P. S.; Knutsen, E. M. (2012). "Phylogenetic relationships of Upper Jurassic (Middle Volgian) plesiosaurians (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Agardhfjellet Formation of central Spitsbergen, Norway" (PDF). Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92: 277–284.

- ^ Buffetaut, E.; Suteethorn, V.; Tong, H.; Amiot, R. (2008). "An Early Cretaceous spinosaur theropod from southern China". Geological Magazine. 145 (5): 745–748. Bibcode:2008GeoM..145..745B. doi:10.1017/S0016756808005360. S2CID 129921019.

- ^ Maryańska, T. (1976). "Aberrant pliosaurs from the Oxfordian of Poland". Prace Museum Ziemi. 20: 201–206.

- ^ Madzia, D.; T., Szczygielski; Wolniewicz, A. S. (2021). "The giant pliosaurid that wasn't—revising the marine reptiles from the Kimmeridgian, Upper Jurassic, of Krzyżanowice, Poland". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66 (1): 99–129. doi:10.4202/app.00795.2020. S2CID 231801208.

- ^ a b c Sachs, S.; Madzia, D.; Thuy, B.; Kear, B. P. (2023). "The rise of macropredatory pliosaurids near the Early-Middle Jurassic transition". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 17558. Bibcode:2023NatSR..1317558S. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-43015-y. PMC 10579310. PMID 37845269.

- ^ a b c Martill, D. M.; Jacobs, M. L.; Smith, R. E. (2023). "A truly gigantic pliosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation (Upper Jurassic, Kimmeridgian) of England". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 134 (3): 361–373. Bibcode:2023PrGA..134..361M. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2023.04.005. S2CID 258630597.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ketchum, H. F.; Benson, R. B. J. (2011). "The cranial anatomy and taxonomy of Peloneustes philarchus (Sauropterygia, Pliosauridae) from the Peterborough member (Callovian, Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom". Palaeontology. 54 (3): 639–665. Bibcode:2011Palgy..54..639K. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01050.x. S2CID 85851352.

- ^ a b Benson, R. B. J.; Evans, M.; Smith, A. S.; Sassoon, J.; Moore-Faye, S.; Ketchum, H. F.; Forrest, R. (2013). "A Giant Pliosaurid Skull from the Late Jurassic of England". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e65989. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...865989B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065989. PMC 3669260. PMID 23741520.

- ^ a b c Benson, R. B. J.; Druckenmiller, P. S. (2014). "Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition". Biological Reviews. 89 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/brv.12038. PMID 23581455. S2CID 19710180.

- ^ a b c d Duff, K. L. "Palaeoecology of a bituminous shale – the Lower Oxford Clay of central England". Palaeontology. 18 (3): 443–482.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mettam, C.; Johnson, A. L. A.; Nunn, E. V.; Schöne, B. R. (2014). "Stable isotope (δ18O and δ13C) sclerochronology of Callovian (Middle Jurassic) bivalves (Gryphaea (Bilobissa) dilobotes) and belemnites (Cylindroteuthis puzosiana) from the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation (Cambridgeshire, England): evidence of palaeoclimate, water depth and belemnite behaviour" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 399: 187–201. Bibcode:2014PPP...399..187M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.01.010. hdl:10545/592777. S2CID 129844404.

- ^ a b Hudson, J. D.; Martill, D. (1994). "The Peterborough Member (Callovian, Middle Jurassic) of the Oxford Clay Formation at Peterborough, UK". Journal of the Geological Society. 151 (1): 113–124. Bibcode:1994JGSoc.151..113H. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.151.1.0113. S2CID 130058981.

- ^ a b c Belin, S.; Kenig, F. (1994). "Petrographic analyses of organo-mineral relationships: depositional conditions of the Oxford Clay Formation (Jurassic), UK". Journal of the Geological Society. 151 (1): 153–160. Bibcode:1994JGSoc.151..153B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1001.7308. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.151.1.0153. S2CID 131433536.

- ^ Kenig, F; Hudson, J. D.; Damsté, J. S. S.; Popp, B. N. (2004). "Intermittent euxinia: Reconciliation of a Jurassic black shale with its biofacies". Geology. 32 (5): 421–424. Bibcode:2004Geo....32..421K. doi:10.1130/G20356.1.

- ^ Martill, D. M. (1991), "Fish", in Martill, D. M.; Hudson, J. D. (eds.), Fossils of the Oxford Clay (PDF), London: The Palaeontological Association, pp. 197–225, ISBN 0901702463

- ^ Johnson, M. M.; Young, M. T.; Brusatte, S. L. (2020). "The phylogenetics of Teleosauroidea (Crocodylomorpha, Thalattosuchia) and implications for their ecology and evolution". PeerJ. 8: e9808. doi:10.7717/peerj.9808. PMC 7548081. PMID 33083104.

- ^ Young; Brignon, A.; Sachs, S.; Hornung, J. J.; Foffa, D.; Kitson, J. J. N.; Johnson, M. M.; Steel, L. (2021). "Cutting the Gordian knot: A historical and taxonomic revision of the Jurassic crocodylomorph Metriorhynchus". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 192 (2): 510–553. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa092.

- ^ Sachs, S.; Young, M.T.; Abel, P.; Mallison, H. (2019). "A new species of the metriorhynchid crocodylomorph Cricosaurus from the Upper Jurassic of southern Germany" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 64 (2): 343–356. doi:10.4202/app.00541.2018.

- ^ a b Ketchum, H. F.; Benson, R. B. J. (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: Evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129. ISSN 0038-6804. OCLC 2450768.

- ^ Noè, L. F.; Liston, J.; Evans, M. (2003). "The first relatively complete exoccipital-opisthotic from the braincase of the Callovian pliosaur, Liopleurodon" (PDF). Geological Magazine. 140 (4): 479–486. Bibcode:2003GeoM..140..479N. doi:10.1017/S0016756803007829. S2CID 22915279. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Noè, L. F. (2001). A taxonomic and functional study of the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) Pliosauroidea (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) (PhD). Chicago: University of Derby.

- ^ a b c Cruickshank, A. R. I.; Martill, D. M.; Noe, L. F. (1996). "A pliosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) exhibiting pachyostosis from the Middle Jurassic of England". Journal of the Geological Society. 153 (6): 873–879. Bibcode:1996JGSoc.153..873C. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.153.6.0873. S2CID 129602868.