Asthall barrow

51°47′20″N 01°34′52″W / 51.78889°N 1.58111°W

Asthall barrow is a high-status Anglo-Saxon burial mound from the seventh century AD. It is located in Asthall, Oxfordshire, and was excavated in 1923 and 1924.

Location

[edit]Asthall barrow is located along the strip of the A40 connecting the towns of Witney and Burford; it is immediately north of the A40 where it connects to Burford road, and just south of the byroad leading off Burford to Asthall and Swinbrook.[1][2] The barrow is prominently located.[3] It sits by Akeman Street where the Roman road crossed the River Windrush, the site of a onetime Roman settlement.[3][4] It has expansive views, and overlooks the Thames Valley from Lechlade to Wytham Hill.[1] To the north it looks out at Leafield barrow; to the south appears Faringdon Hill and beyond it the Berkshire Downs at White Horse Hill, while to the southeast Sinodun Hill near Dorchester appears, with the Chilterns in the distance.[1] The barrow gives its name to surrounding structures, such as Barrow Plantation, Barrow Farmhouse, and Asthall Barrow Roundabout.[2]

Architecture

[edit]

The barrow stands 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) high, and is about 55 ft (17 m) in diameter.[5] It was recorded as 8 ft 6 in (2.6 m) high around 1907,[6] but, in 1923, as 12 ft (3.7 m) high.[7] It is surrounded by a 4 ft 6 in (1.37 m) high dry stone retaining wall.[5][7] Once covered in trees including beeches and firs, likely planted in the nineteenth century,[5][7] the barrow is now topped by a single, prominent, sycamore; the remaining growth was removed during conservation work in 2017 or 2018.[8] The presence of Romano–British grey wares in the barrow's soil, like the downward sloping surrounding land, suggests that the barrow may have been constructed by scraping up the surrounding topsoil.[5] The land around the barrow is cultivated up to its edges, and in 1992 was planted with barley crops.[9]

Originally the barrow probably stood larger; in 1923 an elliptical section surrounding the southwest circumference was recorded as approximately 4 in (10 cm) higher than the field, suggesting that it was once a part of the barrow.[5][10] That the barrow's finds were not in the centre of its present dimensions also suggests that its original dimensions were somewhat different.[5] Slippage of the barrow's soil may also help explain the changed dimensions, and the recorded reduction in height over time.[5]

Excavation

[edit]

The barrow was excavated in August 1923, and again in 1924, by George Bowles, the brother in law of the second Baron Redesdale, who owned the land.[11][12] Permission to excavate had been unsuccessfully sought in 1872, on behalf of George Rolleston.[13] The 1923 excavation was overseen by Bowles, although actually carried out by a Tom Arnold and five helpers.[14] Bowles was also aided by Edward Thurlow Leeds, then assistant keeper at the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum; Leeds offered suggestions, visited the site, and published the main discoveries.[11][12] He published the 1923 excavation along with an excavation plot by Bowls in The Antiquaries Journal in April 1924, and briefly discussed the 1924 excavation 15 years later in a chapter of A History of Oxfordshire.[15][16][12] Both excavations are also plotted, probably by Leeds, on a piece of blue linen held by the Ashmolean.[12]

Bowles dug an irregular, seven-cornered polygonal trench in 1923, and in 1924 added a rectangular trench to its side, along with four 18-inch-square trenches in the area of the raised surrounding soil.[5] He began by sinking a shaft 12 feet square and 12 feet deep; to this he added several subsequent extensions, each to the level of the field or below.[7][5] He labeled the corners A–H on his plot, omitting the F.[17][18] Bowles determined the barrow to be undisturbed and to consist of earth mixed with stones, along with the occasional sherd of Romano–British pottery.[7][5][note 1] The surface level was coated in yellowish clay, perhaps brought up from the River Windrush nearby.[21][22] This faded away toward corner B, Bowles noted, but was prevalent around corner G, the southern limit of the excavation.[23] Atop the clay Bowles found an abundance of charcoal and ashes, six inches thick in places (such as at point V on his plot), and forming only a thin covering elsewhere.[23][22] Bowles also recorded a large charred timber, between points G and H.[23][22]

Grave goods

[edit]The barrow contained a large assemblage of items, of a quality indicating the high-status nature of the burial.[24] There were at least seven vessels: three pottery, two hand-made jars, a Merovingian bottle, and a small silver bowl or cup.[20] Fragments of foil, five of which were stamped with zoomorphic interlace patterns, suggest the burial of a decorated drinking horn, and a pear-shaped mount was both patterned and gilded.[25] Other items appear to have been made of bone, and were likely pieces from a gaming set.[26] The finds were donated to the Ashmolean, where they were given the accession numbers 1923.769–782, and 1949.297.[12]

| Accession | Image | Category | Description | Material | Dimensions | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923.769 |  | Vessel | Merovingian wheel-made bottle | Pottery | 247mm (h); 168mm (d) | [27][28][29][30] | |

| 1923.770 |  | Vessel | Hand-made pot | 125mm (h); 110mm (d) | [31][32] | ||

| 1923.771 |  | Vessel | Hand-made pot | 115mm (h); 127mm (d) | [33][34] | ||

| 1923.778 | Vessel | Bowl or cup | Silver | 13+ heavily oxidised fragments, including rim and body pieces | |||

| 1923.776 |  | Vessel | Byzantine bowl | Cast copper alloy | 4+ fragments, including rim, hinge-loop, and foot-ring | [35] | |

| 1923.779 | Vessel | Bowl or cauldron | Copper alloy | Unburnt sheet-metal body fragment; rim fragment from same or similar vessel | [35][36] | ||

| 1923.779 | Vessel | Fittings for drinking horn(s), bottle(s), or cup(s) | Copper alloy | Sheet metal including repoussé foils decorated in Salin Style II and/or with billeted border, fluted binding strips with dome-headed rivets and U-sectioned rim-edge bindings | |||

| 1923.779 | Vessel | Vessel | Copper alloy | 3–3.5mm (d) | Several fragments of sheet metal with one edge rolled into a narrow tube | ||

| 1923.774 |  | Strap fittings | Strap end | Cast copper alloy | 41mm (l); 19mm (w) | Mineralized textile on back | [37][38] |

| 1923.775 | Strap fittings | Looped strap tab | Cast copper alloy | 35mm (l); 11mm (w); 13mm (d) | |||

| 1923.777 |  | Strap fittings | Hinged strap attachment | Cast copper alloy | 22mm (l); 14.5mm (w) | Includes iron hinge-pin | [39][40] |

| 1923.779 | Strap fittings | Looped strap mount | Cast copper alloy | 12.5mm (l); 13mm (w) | [41] | ||

| 1923.775 |  | Strap fittings | Openwork swivel suspension fitting | Cast copper alloy | Openwork cuboid, 12.5mm (l), 9mm (w); swivel loop, 20mm (l); looped strap tab, 19.5mm (l), 6mm (w) | [42][43] | |

| 1923.779 | Strap fittings | Disc-headed rivets | 8mm (d); 5mm (l) | 3 fragments. Heads decorated with concentric rings | [44] | ||

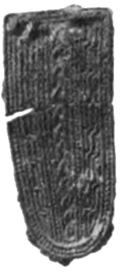

| 1923.773 |  | Strap fittings | Pear-shaped mount | Cast copper alloy; gilt | 47mm (l) (reconstructed) | Salin Style II on front; two cast-in-one disc-ended rivets on back | [45] |

| 1923.782 | Gaming set | Counters | Bone | 30mm (d); 4mm (h) | 26 fragments, plano-convex | ||

| 1949.297 | Gaming set | Die | Antler | 14mm cube | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Rectangular-headed rivet | Silver | Head, 6.7mm (l), 5mm (w); shank, 7mm (l) | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Disc | Silver | 17mm (d); 4.3mm (th) | Bevelled edge | ||

| 1923.779 |  | Unassignable items | "Silver" strap mount | Copper alloy | 19mm (l) (extant); 6mm (w) | Cast. Two rivets on back corroded green; front gray. | [46][47] |

| 1923.779 |  | Unassignable items | Two crescentic studs | Copper alloy | 15mm (d) | Decorated with punched triangles. Rivet on back. | [48][49] |

| 1923.779 |  | Unassignable items | Sunken-field stud | Copper alloy | 10.5mm (d); 2.5mm (h); shank 8mm (l) | Cast. Dome-headed rivet passes through centre of sunken field and bent flat on underside. | [48][50] |

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Disc-headed rivet | Copper alloy | 6.5mm (d); shank 5.5mm (l) (extant) | Plain | ||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Dome-headed rivet pin | Copper alloy | 3.3mm (d); 9.5mm (l); shank 8.5mm (l) | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Relief-decorated disc or ring | Copper alloy | 15mm (l); 14mm (w) | Cast. Fragment with thickened edge and hint of curvature. Northed ridge border and Salin Style I zoomorphic field. | ||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Plain disc | Copper alloy | 23mm (d) | Plain. | ||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Unidentified fragments | Copper alloy | Constitutes the majority of the material catalogued under 1923.779. Includes sandwiched foil fragments, pieces covered with/incorporating corrosion products, charcoal and soil, generally thicker than the foils, and globules of melted metal. May come from the copper-alloy vessels or unassignable items. | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | "Nails" | Iron | 11.5–22mm (l) | 4 fragments | ||

| 1923.780 | Unassignable items | Inlays? | Iron | 4–5mm, 15mm (w) | 55 fragments with flat rectangular or slightly plano-convex section, most with plain outer surface and grooved or cross-grooved inner surface, some also with grooved outer surface, and two with cross-hatched edges | ||

| 1923.781 | Unassignable items | "Rods" | Iron | 46mm (l) (max); 6.5mm (d) (max) | 11 fragments, slightly curved and tapered | ||

| n/a | Cremated bone | Four finger bones; fragments of jaw; roots of canine and lower molar | Human bone | ||||

| n/a | Cremated bone | Left tibia; right lateral cuneiform; sesamoid; likely metatarsal | horse bone | ||||

| n/a | Cremated bone | Astragalus; possible tail vertebrae; skull fragments | sheep bone | ||||

| 1923.772 | From barrow make-up | Romano–British pottery sherds | Worn residual material | [10] |

Conservation

[edit]

The Asthall barrow was designated a scheduled monument on 16 May 1934.[2] Historic England, which maintains the list of such monuments, noted that the barrow "is one of the best preserved examples of a type of burial mound of which there are about ten examples in West Oxfordshire", and that "[d]espite partial excavation and recent animal burrowing it will contain archaeological and environmental evidence relating to its construction and the landscape in which it was built."[2] Historic England added that the "survival of part of its original drystone retaining wall is an unusual feature", but that regardless, "[a]s a rare monument class all positively identified examples are considered worthy of preservation."[2]

In 2009, the barrow was added to Historic England's "Heritage At Risk Register", a project intended to identify and protect historic sites threatened by neglect, decay, or development.[51] The 2009 list was the first to include scheduled monuments that are archaeological sites; previous iterations had included only listed buildings, structural scheduled monuments, registered battlefields, and protected wreck sites.[52] The barrow remained on the at-risk register through 2017.[53][54] From 2009 to 2014, its condition was described as "declining" with "generally unsatisfactory with major localised problems," and its principal vulnerability was given as scrub and tree growth.[55][56][57][58][59][60] Its principal vulnerability was changed to collapse by 2015,[61] although by 2016 its condition was upgraded to "improving."[62] In 2017, the barrow's final year on the register, its principal vulnerability was given as extensive rabbit burrowing.[63] The barrow was listed as "saved" and removed from the register the following year, following removal of trees and scrub, and work to exclude rabbits; the large sycamore tree atop the barrow was left in place.[8] The work was done in partnership with the owners, and voluntary wardens from the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[8]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Bowles, whose daughter described him as a "gentleman amateur", may not be an authoritative voice for the idea that the barrow was hitherto intact.[19] Likewise, one of several explanations for the wide and seemingly random distribution of objects within is that the barrow had previously been opened.[20] Absent a re-excavation, Bowles's claim is thus uncertain.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Leeds 1924, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d e Historic England Asthall Barrow.

- ^ a b Williams 2006, p. 202.

- ^ Cassey and Co. 1868, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 98.

- ^ Potts 1907, p. 345.

- ^ a b c d e Leeds 1924, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Historic England 2018.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Leeds 1924, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b Leeds 1924, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b c d e Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 96.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 114 n.2.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 117.

- ^ Leeds 1924.

- ^ Leeds 1939.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 115.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 98–00.

- ^ a b Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 96, 101.

- ^ a b Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 101.

- ^ Leeds 1924, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b c Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Leeds 1924, p. 116.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 112.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 105.

- ^ Leeds 1924, pp. 122–123, figs. 8–9.

- ^ Fox 1924.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101–102, 106, 110, 113, 124, fig. 16C.

- ^ Ashmolean Merovingian bottle.

- ^ Leeds 1924, pp. 121–122, fig. 7 (left).

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101, 106, 124, fig. 16A.

- ^ Leeds 1924, pp. 121–122, fig. 7 (right).

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101, 124, fig. 16B.

- ^ a b Leeds 1924, pp. 119–120, fig. 5K.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101–104, 124, fig. 18A, pl. 3.3.

- ^ Leeds 1924, pp. 120–121, fig. 5D.

- ^ Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18c.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 120, fig. 5G.

- ^ Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18b.

- ^ Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18a.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 120, fig. 5B.

- ^ Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18d.

- ^ Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18e.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 121, figs. 5C, 6.

- ^ Leeds 1924, p. 119, fig. 5F.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 105, 124, pl. 4.14.

- ^ a b Leeds 1924, p. 120, fig. 5E.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 126, pl. 4.16.

- ^ Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 105, 126, pl. 4.17.

- ^ Parfitt & Whimster 2009, pp. 3, 67.

- ^ Parfitt & Whimster 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2017.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2018.

- ^ Parfitt & Whimster 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2011, p. 70.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2013, p. 67.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Heritage at Risk 2017, p. 63.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Asthall". History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Berkshire and Oxfordshire, with an Excellent Map of Each County. London: Edward Cassey and Co. 1868. pp. 14–15.

- "Asthall Barrow - an Anglo-Saxon Burial". Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017.

- "Bottle". Ashmolean Museum. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Colvin, Christina; Cragoe, Carol; Ortenberg, Veronica; Peberdy, Robert B.; Selwyn, Nesta & Williamson, Elizabeth (2006). "Asthall: Introduction". In Townley, Simon (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. Vol. XV. London: Institute of Historical Research. pp. 37–48.

- Colvin, Christina; Cragoe, Carol; Ortenberg, Veronica; Peberdy, Robert B.; Selwyn, Nesta & Williamson, Elizabeth (2006). "Asthall: Economic History". In Townley, Simon (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. Vol. XV. London: Institute of Historical Research. pp. 55–64.

- Davies, Wendy & Vierck, Hayo (December 1974). "The Contexts of Tribal Hidage: Social Aggregates and Settlement Patterns". Frühmittelalterliche Studien. 2: 223–302. doi:10.1515/9783110242072.223. S2CID 201729051.

- Dickinson, Tania M. (October 1976). The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa AD 400–700 (Ph.D.). Vol. I. University of Oxford.

- Dickinson, Tania M. (October 1976). The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa AD 400–700 (Ph.D.). Vol. II. University of Oxford.

- Dickinson, Tania M. (October 1976). The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa AD 400–700 (Ph.D.). Vol. III. University of Oxford.

- Dickinson, Tania M. & Speake, George (1992). "The Seventh-Century Cremation Burial in Asthall Barrow, Oxfordshire: A Reassessment" (PDF). In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Age of Sutton Hoo: The seventh century in north-western Europe. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 95–130. ISBN 0-85115-330-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2019.

- Fox, Cyril (October 1924). "A Jug of the Anglo-Saxon Period". The Antiquaries Journal. IV (4). Society of Antiquaries of London: 371–374. doi:10.1017/S0003581500006168. S2CID 163791758.

- "Heritage at Risk 2018". Historic England. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Historic England. "Asthall Barrow: an Anglo-Saxon burial mound 100m SSW of Barrow Farm (1008414)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (April 1924). "An Anglo-Saxon Cremation-burial of the Seventh Century in Asthall Barrow, Oxfordshire". The Antiquaries Journal. IV (2). Society of Antiquaries of London: 113–126. doi:10.1017/S0003581500005552. S2CID 161746919.

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (1939). "Anglo-Saxon Remains". In Salzman, Louis Francis (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. Vol. I. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 346–372.

- MacGregor, Arthur & Bolick, Ellen (1993). "A Summary Catalogue of the Anglo-Saxon Collections (Non-Ferrous Metals)". British Archaeological Reports. 230. ISBN 978-0860547518.

- Manning, Percy (April 1898). "Notes on the Archæology of Oxford and its Neighbourhood". The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal. 4 (1). Berkshire Archaeological Society: 9–10.

- Meaney, Audrey (1964). A Gazetteer of Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Parfitt, Clare & Whimster, Rowan, eds. (June 2009). Heritage at Risk Register 2009: South East. London: English Heritage.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2010: South East. London: English Heritage. July 2010.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2011: South East. London: English Heritage. October 2011.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2012: South East. London: English Heritage. September 2012.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2013: South East. London: English Heritage. October 2013.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2014: South East. London: English Heritage. October 2014.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2015. London: English Heritage. October 2015.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2016. London: English Heritage. October 2016.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2017. London: English Heritage. October 2017.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2018. London: English Heritage. November 2018.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2010: South East. London: English Heritage. July 2010.

- Pickering, A. J. (April 1932). "A Hanging-bowl from Leicestershire". The Antiquaries Journal. XII (2). Society of Antiquaries of London: 174–175. doi:10.1017/S0003581500047235. S2CID 246043060.

- Potts, William (1907). "Ancient Earthworks". In Page, William (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. Vol. II. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 303–349.

- "Site Name: Asthall". Oxfordshire's Historic Archives. Ashmolean Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Timby, Jane (January 1993). A40 Witney Bypass to Sturt Farm Improvement: Archaeological Survey (PDF). Cirencester: Cotswold Archaeological Trust.

- Williams, Howard (2006). Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain. Cambridge Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511489594. ISBN 978-0-511-48959-4.

- Windle, Bertram (July 1901). "A Tentative List of Objects of Prehistoric and Early Historic Interest in the Counties of Berks, Bucks and Oxford". The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal. 7 (2). Berkshire Archaeological Society: 43–47.