Santo Stefano al Monte Celio

| Basilica of Saint Stephen in the Round on the Caelian Hill | |

|---|---|

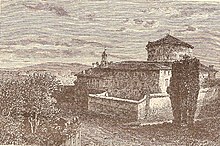

Santo Stefano Rotondo in a painting by Ettore Roesler Franz in the 19th century. | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 41°53′04″N 12°29′48″E / 41.88452°N 12.49676°E | |

| Location | Via Santo Stefano Rotondo 7, Rome |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Website | Official Website |

| History | |

| Status | Minor basilica, titular church, rectory church, national church |

| Dedication | Saint Stephen Protomartyr (also associated unofficially with King Saint Stephen of Hungary) |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Paleochristian |

| Groundbreaking | 5th century |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Width | 45 m (148 ft) |

| Nave width | 20 metres (66 ft) |

| Clergy | |

| Cardinal protector | Friedrich Wetter |

The Basilica of St. Stephen in the Round on the Caelian Hill (Italian: Basilica di Santo Stefano al Monte Celio, Latin: Basilica S. Stephani in Caelio Monte) is an ancient basilica and titular church in Rome, Italy. Commonly named Santo Stefano Rotondo, the church is Hungary's "national church" in Rome, dedicated to both Saint Stephen, the first Christian martyr, and Stephen I, the canonized first king of Hungary . The minor basilica is also the rectory church of the Pontifical Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum.

Since 1985, the cardinal priest who holds the title of S. Stephano has been Friedrich Wetter.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

The earliest church was consecrated by Pope Simplicius between 468 and 483. It was dedicated to the protomartyr Saint Stephen, whose body had been discovered a few decades before in the Holy Land, and brought to Rome. The church was the first in Rome to have a circular plan. Its architecture is unique in the Late Roman world.[1] Saint Stefano was probably financed by the wealthy Valerius family whose estates covered large parts of the Caelian Hill. Their villa stood nearby, on the site of the present-day Hospital of San Giovanni Addolorata. Saint Melania the Elder, a member of the family, was a frequent pilgrim to Jerusalem and died there, so the family had connections to the Holy Land.

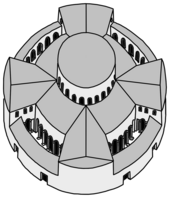

The church was originally commissioned by Pope Leo I (440-461), with the date confirmed by ancient coins and by dendrochronology, which places the wood used in the beams of the roof to around 455 AD, but was not consecrated until after his death. The original church had three concentric ambulatories flanked by 22 Ionic columns, surrounding the central circular space surmounted by a tambour that is 22 m (72 ft) high and 22 m wide). There were 22 windows in the tambour but most of them were walled up in the 15th-century restoration. The central ambulatory had a diameter of 42 m (138 ft), and the outer one a diameter of 66 m (217 ft). Four side chapels extended from the middle ambulatory to the outer ambulatory, forming a Greek cross.[2]

The church was embellished by Pope John I and Pope Felix IV in the 6th century with mosaics and colored marble. It was restored in 1139–1143 by Pope Innocent II, who abandoned the outer ambulatory and three of the four side chapels. He also had three transverse arches added to support the dome,[2] enclosed the columns of the central ambulatory with brick to form the new outer wall, and walled up 14 of the windows in the drum.

In the Middle Ages, Santo Stefano Rotondo was in the charge of the Canons Regular of the Lateran, but as time went on it fell into disrepair. In the middle of the 15th century, Flavio Biondo (Flavius Blondus) praised the marble columns, marble-covered walls, and cosmatesque works-of-art of the church, but he added that unfortunately "nowadays Santo Stefano Rotondo has no roof". Blondus claimed that the church was built on the remains of an ancient Temple of Faunus. Excavations in 1969 to 1975 revealed that the building was not converted from a pagan temple but was always a church, erected under Constantine I in the first half of the 4th century.

In 1454, Pope Nicholas V entrusted the ruined church to the Pauline Fathers, the only Catholic Order founded by Hungarians. This is the reason why Santo Stefano Rotondo later became the unofficial church of the Hungarians in Rome. The church was restored in the 1450s by Bernardo Rossellino, probably under the guidance of Leon Battista Alberti.[3]

In 1579, the Hungarian Jesuits joined the Pauline Fathers. The Collegium Hungaricum, established by István Arator in 1579, was merged with the Collegium Germanicum in 1580, and became the Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum,[4] because very few Hungarian students were able to travel to Rome from the Turkish-occupied, Kingdom of Hungary.

On a visit to Rome in 1819 J. M. W. Turner made sketches of both the exterior and interior.[5]

The Cardinal Priest of the Titulus S. Stephani in Coelio Monte has been Friedrich Wetter since 1985. His predecessor, József Mindszenty, was famous as the persecuted Catholic leader of Hungary under the Communist dictatorship.

Exterior

[edit]

Although the inside is circular, the exterior is on a cruciform plan. The entrance has a portico with five arches on tall ancient granite columns with Corinthian capitals, added in the 12th century, by Pope Innocent II.[2]

Interior

[edit]The walls of the church are decorated with numerous frescoes, including those of Niccolò Circignani (Niccolò Pomarancio) and Antonio Tempesta portraying 34 scenes of martyrdom,[5] commissioned by Gregory XIII in the 16th century. Each painting has a titulus or inscription explaining the scene and giving the name of the emperor who ordered the execution, as well as a quotation from the Bible.

Works of art

[edit]The altar was made by the Florentine artist Bernardo Rossellino in the 15th century. The painting in the apse shows Christ between two martyrs. An ancient chair of Pope Gregory the Great from around 580 AD is preserved here.

The Chapel of Ss. Primo e Feliciano has mosaics from the 7th century. One of them shows the martyrs Primus and Felician flanking a crux gemmata (jewelled cross). In 648 the chapel was built by Pope Theodore I who brought here the relics of the martyrs and buried them (together with the remains of his father).

Hungarian Chapel

[edit]Unlike nationals of other European nations, Hungarians lacked a national church in Rome after the old Santo Stefano degli Ungheresi in the Vatican was pulled down to make way for the sacristy of St Peter's Basilica in 1778. As a compensation for the loss of the ancient church, Pope Pius VI built a Hungarian chapel in Santo Stefano Rotondo according to the plans of Pietro Camporesi.

The 'Hungarian chapel' is dedicated to Stephen I of Hungary, Szent István, the canonized first king of the Magyars. The feast of St Stephen is celebrated on 20 August. Hungarian pilgrims frequently visit the chapel.

Hungarian experts took part in the ongoing restoration and archeological exploration of the church during the 20th century together with German and Italian colleagues. Notable Hungarian visitors were Vilmos Fraknói, Frigyes Riedl, and László Cs. Szabó, who all wrote about the history and importance of Santo Stefano.

Recent archeological explorations revealed the late-antique floor of the church in the chapel. The floor is composed of coloured marble slabs and was restored in 2006 by an international team led by Zsuzsanna Wierdl.

The frescoes of the chapel were painted in 1776 but older strata of paintings were recently discovered under them.

Burials

[edit]Archdeacon János Lászai, canon of Gyulafehérvár, was buried in the Santo Stefano Rotondo in 1523. Lászai left Hungary and moved to Rome where he became a papal confessor.[6] His burial monument is an interesting example of Renaissance funeral sculpture. The inscription says: "Roma est patria omnium" (Rome is everybody's fatherland).

There is a tablet recording the burial here of the Irish king Donnchad mac Brian, son of Brian Bóruma and King of Munster, who died in Rome in 1064.[7]

Mithraeum

[edit]Under the church there is a 2nd-century mithraeum, related to the presence of the barracks of Roman soldiers in the neighbourhood. The cult of Mithras was especially popular among soldiers. The remains of Castra Peregrinorum, the barracks of the peregrini, officials detached from provincial armies for special service to the capital, were found under Santo Stefano Rotondo. The mithraeum belonged to Castra Peregrinorum but it was probably also attended by the soldiers of Cohors V Vigilum, whose barracks stood nearby on the other side of Via della Navicella.

The mithraeum is being excavated. The remains of the Roman military barracks (from the Severan Age) and the mithraeum under the church remain closed to the public.[when?] The coloured marble bas-relief "Mithras slaying the bull" from the 3rd century is today in the Museo Nazionale Romano.

List of cardinal priests of the church

[edit]The titulus S. Stephani in Coelio Monte was cited for the first time in the Roman synod of 499.

- Marcello (499)

- Benedetto (993)

- Crescenzio (1015)

- Sasso de Anagni (1116–1131)

- Martino Cybo (1132–1142)

- Raniero (1143–1144)

- Villano Gaetani (1144–1146)

- Gerardo (1151–1158)

- Gero (1172), pseudocardinal of the Antipope Calixtus III

- Vibiano (1175–1184)

- Giovanni di Salerno (1190–1208)

- Robert of Courçon (or de Corzon, or Cursonus) (1212–1219)

- Michel Du Bec-Crespin (1312–1318)

- Pierre Le Tessier (1320–1325)

- Pierre de Montemart (1327–1335)

- Guillaume d'Aure, O.S.B. (1339–1353)

- Élie de Saint-Irier (or Saint Yrieux) (1356–1363)

- Guillaume d'Aigrefeuille le Jeune (1367–1401)

- Gugilemo d'Altavilla (1384–1389)

- Angelo Cino (or Ghini Malpighi) (1408–1412)

- Pierre Ravat (or Rabat) (1408–1417), pseudocardinal of the Antipope Benedict XIII

- Pierre of Foix, (1417–1431)

- Jean Carrier (1423-c. 1429), pseudocardinal of the Antipope Benedict XIII

- Vacant (1431–1440)

- Renault de Chartres (or Renaud) (1440–1444)

- Jean d'Arces (1444–1449), pseudocardinal of the Antipope Felix V

- Jean Rolin (1448–1483)

- Giovanni Giacomo Sclafenati (1483–1484); in commendam (1484–1497)

- Vacant (1497–1503)

- Jaime Casanova (1503–1504)

- Antonio Pallavicini Gentili (or Antoniotto), in commendam (1504–1505)

- Antonio Trivulzio, senior (1505–1507)

- Melchior von Meckau (1507–1509)

- François Guillaume de Castelnau-Clermont-Ludève (1509–1523)

- Bernardo Clesio (1530–1539)

- David Beaton (1539–1546)

- Giovanni Morone (1549–1553)

- Giovanni Angelo Medici (1553–1557) later Pope Pius IV

- Fulvio Giulio della Corgna (1557–1562)

- Girolamo da Correggio (1562–1568)

- Diego Espinosa (1568–1572)

- Zaccaria Delfino (1578–1579)

- Matteo Contarelli (1584–1585)

- Federico Cornaro (1586–1590)

- Antonio Maria Sauli (1591–1603)

- Giacomo Sannesio (1604–1621)

- Lucio Sanseverino (1621–1623)

- Bernardino Spada (1627–1642)

- John de Lugo (1644)

- Giovanni Giacomo Panciroli (1644–1651)

- Marcello Santacroce Publicola (1652–1674)

- Bernardino Rocci (1675–1680)

- Raimondo Capizucchi (1681–1687)

- Francesco Bonvisi (1689–1700)

- Giovanni Battista Tolomei (1712–1726)

- Giovanni Battista Salerno (1726–1729)

- Camillo Cybo (1729–1731)

- Antonio Saverio Gentili (1731–1747)

- Filippo Maria Monti (1747–1754)

- Fabrizio Serbelloni (1754–1763)

- Pietro Paolo Conti (1763–1770)

- Ludovico Calini (1771–1782)

- Vacant (1782–1786)

- Niccolò Colonna di Stigliano (1786–1796)

- Étienne-Hubert de Cambacérès (1805–1818)

- Vacant (1818–1834)

- Francesco Tiberi (1834–1839)

- Vacant (1839–1845)

- Fabio Maria Asquini (1845–1877)

- Manuel García Gil (1877–1881)

- Paul Melchers (1885–1895)

- Sylvester Sembratovych (1896–1898)

- Jakob Missia (1899–1902)

- Lev Skrbenský z Hříště (1902–1938)

- Vacant (1938–1946)

- József Mindszenty (1946–1975)

- Vacant (1975–1985)

- Friedrich Wetter (1985-incumbent)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Claridge, Amanda. (1998). Cunliffe, Barry (ed.). Rome : an Oxford archaeological guide to Rome. Toms, Judith., Cubberley, Tony. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 308. ISBN 9780192880031. OCLC 37878669.

- ^ a b c "The Church of Santo Stefano Rotondo al Celio", Turismo Roma, Major Events, Sport, Tourism and Fashion Department

- ^ Rossellino, Bernardo. Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. 2011-10-31. doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00156129.

- ^ Aldásy, Antal. "Stephan Szántó (Arator)." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ a b Moorby, Nicola. "J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours", Tate, May 2008

- ^ Érszegi, Géza (2013). "A Paenitentiaria Apostolica dokumentumai „in partibus"" (PDF). In Homoki-Nagy, Mária (ed.). Ünnepi kötet Dr. Blazovich László egyetemi tanár 70. születésnapjára. Szeged: Szegedi Tudományegyetem. p. 210.

- ^ * Bracken, Damian (2004). "Mac Briain, Donnchad (d. 1064)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20452. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

[edit]- Macadam, Alta. Blue Guide Rome. A & C Black, London (1994), ISBN 0713639393

- Federico Gizzi, Le chiese medievali di Roma (Rome, Newton Compton, 1998).

- H. Brandenburg und J. Pál (edd), Santo Stefano Rotondo in Roma. Archeologia, storia dell'arte, restauro. Archäologie, Bauforschung, Geschichte. Akten der internationalen Tagung (Rom 1996) (Wiesbaden, 2000).

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 589, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790

External links

[edit]- Photos of the discovered Roman floor, with Hungarian text only

- Official Homepage of the Church Archived 2018-09-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Interactive Nolli Map

![]() Media related to Santo Stefano Rotondo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Santo Stefano Rotondo at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Santa Sofia a Via Boccea | Landmarks of Rome Santo Stefano al Monte Celio | Succeeded by Santa Teresa, Rome |