Battle of Elandslaagte

| Battle of Elandslaagte | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second Boer War | |||||||

Positions at noon, before the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John French Ian Hamilton | Johannes Kock † Adolf Schiel | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,500 18 guns[1] | 1,000 3 guns[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 55 killed 205 wounded | 46 killed 105 wounded 181 missing or captured | ||||||

The Battle of Elandslaagte (21 October 1899) took place during the Second Boer War, and was one of the few clear-cut tactical victories won by the British during the conflict. However, the British force retreated afterwards, throwing away their advantage.

Prelude

[edit]

When the Boers invaded Natal, a force under General Johannes Kock occupied the railway station at Elandslaagte on 19 October 1899, thus cutting the communications between the main British force at Ladysmith and a detachment at Dundee. De Kock's forces consisted mainly of men of the Johannesburg Commando with detachments of German, French, Dutch, American, and Irish Boer foreign volunteers.[2][3]

Learning that the telegraph had been cut, Lieutenant General Sir George White sent his cavalry commander, Major General John French to recapture the station. Arriving shortly after dawn on 21 October, French found the Boers present in strength, with two field guns. He telegraphed to Ladysmith for reinforcements, which shortly afterwards arrived by train.

The battle

[edit]

While three batteries of British field guns bombarded the Boer position, and the 1st Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment advanced frontally in open order, the main attack commanded by Colonel Ian Hamilton (1st Battalion, the Manchester Regiment, 2nd Battalion, the Gordon Highlanders and the dismounted Imperial Light Horse) moved around the Boers' left flank. The sky had steadily been growing dark with thunderclouds, and as the British made their assault, the storm burst. In the poor visibility and pouring rain, the British infantry had to face a barbed wire farm fence, in which several men were entangled and shot. Nevertheless, they cut the wire or broke it down, and occupied the main part of the Boer position.[4]

Some small parties of Boers were already showing white flags when General Kock led a counterattack, dressed in his top hat and Sunday best.[5] He drove back the British infantry in confusion, but they rallied, inspired by Hamilton (and reportedly, a bugler of the Manchesters and a Pipe Major of the Gordons) and charged again. Kock and his companions were killed or severely wounded.

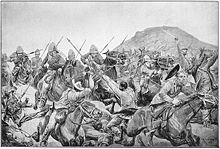

As the remaining Boers mounted their ponies and tried to retreat, two squadrons of British cavalry (from the 5th Lancers and the 5th Dragoon Guards) got among them with lances and sabres, cutting down many. This was one of the few occasions during the Boer war in which a British cavalry charge made contact.[6] The two Boer field guns fell into British hands. They were found to have originally been British and had been captured by the Boers in the aftermath of the Jameson Raid.[7]

Aftermath

[edit]

The way was now clear for the British detachment at Dundee to fall back on the main British force, but Sir George White feared that 10,000 Boers from the Orange Free State were about to attack Ladysmith, and ordered the force at Elandslaagte to fall back there. The British were tired and many officers had been killed, and the retreat became a disorderly scramble.[8] The detachment at Dundee was once again isolated, and was forced to make an exhausting detour before they could reach safety. The Boer forces re-occupied Elandslaagte two days later.[9]

General Kock was captured by the British and died from his wounds shortly after the battle. Also captured in the battle was Adolf Schiel, a German officer who had lived in South Africa since 1878. Schiel, who held the commission of Lieutenant Colonel, led a German commando in the battle. Schiel returned to Germany after the war, but died from wounds he had received at Elandslaagte in 1903.[7]

Among the British dead was Colonel John James Scott-Chisholme, commander in the Imperial Light Horse. He was killed while leading from the front and encouraging his men by waving a coloured sash.[10]

The Battle was also notable for being the first and last battle of the volunteer Hollanderkorps. The Hollanderkorps was a group of ca. 150 Dutch volunteers which had been established a mere month earlier. During the battle the Hollanderkorps suffered 9 fatalities, including Herman Coster, along with fellow officer Cars Geerts de Jonge and seven soldiers: P.J. van den Broek, H. van Cittert, J.A. Lepeltak Kieft, Jan Moora, J.Th. Rummeling, M. Schaink, and F.W. Wagner. A further 35 of the Hollanders were taken prisoner by the British.[11] Among the prisoners was Willem Frederik Mondriaan (brother of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian) who was wounded in the battle. Although he was able to crawl away from the battlefield he was taken prisoner by the British shortly after. He was later sent to Saint Helena as a prisoner of war, returning to South Africa in 1903.[12] Cornelis Vincent 'Cor' van Gogh, the brother of the Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, also fought in the battle[11] where he was wounded and taken prisoner. He died shortly after. The Boer generals were deeply unhappy with the Hollanderkorps' performance, and it was disbanded after the battle though several hundred Dutch volunteers continued to fight in Boer regiments.[11] The names of the deceased Hollanders, including Coster, were inscribed at a monument at the location of the battle. The monument was destroyed by vandals in 2014.[13]

Gallery

[edit]- Sketch of the Battle of Elandslaagte by Willem Frederik Mondriaan

- Monument to the members of the Hollanderkorps who died at the Battle of Elandslaagte before its destruction in 2014

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Battle of Elandslaagte". britishbattles.com. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ Kruger 1964, p. 84.

- ^ Viljoen 1902, p. 24.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, p. 137-138.

- ^ Kruger 1964, p. 86.

- ^ Pakenham 1979, p. 139-140.

- ^ a b Gomm 1971.

- ^ Kruger 1964, p. 88.

- ^ Gillings 2003, p. 33.

- ^ "Roll of Honour – Roxburghshire – Hawick South African". roll-of-honour.com. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Kuitenbrouwer 2017, pp. 233–250.

- ^ Bosch 2013.

- ^ "Horror destruction of Elandslaagte battle memorial". Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Sources

[edit]- Bosch, Jan-Karel (2013), Willem Frederik Mondriaan: 'n Biografiese Skets [Willem Frederik Mondriaan: A Biographical Sketch] (PDF) (in Afrikaans), RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis

- Gillings, Ken (2003). Battles of KwaZulu-Natal. Durban: Art Publishers.

- Gomm, Neville (1971). "The German Commando in the South African War of 1899-1902". Military History Journal. 2 (2). South African Military History Society.

- Kruger, Rayne (1964). Goodbye Dolly Grey. New English Library. ISBN 0-7126-6285-5.

- Kuitenbrouwer, Vincent (2017). "The Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902". In Gosselink, Martine; Holtrop, Maria; Ross, Robert John (eds.). Good Hope: South Africa and The Netherlands from 1600. Amsterdam: Vantilt Publishers. ISBN 978-94-6004-313-0.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1979). The Boer War. Cardinal. ISBN 0-7474-0976-5.

- Viljoen, B. (1902). My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War. London: Hood, Douglas, & Howard.

Further reading

[edit]- Doyle, Arthur Conan (1930). The Great Boer War. London: George Bell & sons.

- McFadden, Pam (2014). The Battle of Elandslaagte: 21 October 1899. 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1-928211-40-2.