George Washington's teeth

George Washington, the first president of the United States, lost all but one of his teeth by the time he was inaugurated, and had at least four sets of dentures he used throughout his life. Made with brass, lead, gold, animal teeth and human teeth; the dentures were primarily created and attended to by John Greenwood, Washington's dentist.[1]

Natural teeth

[edit]In 1756, when Washington was 24 years old, a dentist pulled his first tooth.[2] According to his diary, he paid 5 shillings (£0.25, equivalent to $12 in 2023) to a "Doctor Watson" for the removal. His diary also regularly mentioned troubles such as aching teeth and lost teeth.[3] John Adams said that Washington attributed the loss of his teeth to using them to crack walnuts, but modern historians have suggested that calomel, the mineral form of mercury(I) chloride which Washington was given to treat smallpox, probably contributed to the loss.[4]

On April 30, 1789, the day of his first presidential inauguration, although he had mostly dentures, he had only one remaining natural tooth, a premolar.[5] During that same year, he began wearing full dentures.

Washington's last tooth was given as a gift and keepsake to his dentist John Greenwood.[6]

Dentures

[edit]

During his life, George Washington had four sets of dentures. He began wearing partial dentures by 1781.[6] Despite many people believing they were made of wood, they contained no wood, and often were made of teeth extracted from enslaved people and other materials, including hippopotamus ivory, brass, and gold.[7][8][9] The dentures had metal fasteners, springs to force them open, as well as bolts to keep them together.

Records at Mount Vernon show that Washington bought teeth from slaves.[10] The poor in the Western world had sold teeth as a means of making money since the Middle Ages, which were used as dentures or implants and sold to those of financial means.

During the American Revolutionary War, French dentist Jean Pierre Le Moyer provided services in tooth transplantation. In May of 1784, Washington paid several unnamed slaves 122 shillings (£6.10, equivalent to $184 in 2023) for a total of nine teeth to be implanted by a French doctor, who became a frequent guest on the plantation over the next few years.

While it is unconfirmed that these purchased teeth were for Washington himself, his payment for them suggests that they were in fact for his use, as does a comment from a letter to his wartime clerk Richard Varick: "I confess I have been staggered in my belief in the efficacy of transplantion," he wrote. Washington used teeth sourced from slaves to improve his appearance, a subject of frequent discomfort to him.[11] However, scholars of the Mount Vernon estate dispute this, since the transactions in Washington's accounts state that they were bought "on account for [...]Le Moyer". "If Washington had been purchasing the teeth for himself, there would have been no need for this information; the entries would have simply recorded the item and payment, as when Washington purchased poultry, wild game, fish, and garden produce from enslaved individuals." As such, it remains unknown whether Washington personally used any teeth purchased from slaves or others.[12]

He took the oath of office while wearing a special set of dentures made from ivory, brass and gold built for him by dentist John Greenwood.[7] According to his diaries, Washington's dentures disfigured his mouth and often caused him pain, for which he took laudanum.[13] Washington once wrote that his lips would "bulge" in an unnatural way. This distortion is noticeable on his image on the one-dollar bill, an image taken from the Athenaeum Portrait, an unfinished painting from 1796 by Gilbert Stuart.[7]

Washington once wrote to his dentist, Greenwood, to avoid modifying the dentures "which will, in the least degree force the lips out more than now do, as it does this too much already."[14]

Apart from the disfiguration caused by the dentures, the distress may also be apparent in many of the portraits painted while he was still in office.[13][15][a] He spent constant effort maintaining his dentures, and often had them shipped to Greenwood, for maintenance.[2]

The mistaken belief that Washington's dentures were wooden was widely accepted by 19th century historians and appeared as fact in school textbooks until well into the 20th century. The possible origin of this myth is that ivory teeth quickly became stained and may have had the appearance of wood to observers. A letter from Greenwood to Washington in 1798 advised more thorough cleaning; "the set you sent me from Philadelphia ... was very black ... port wine being sour takes off all the polish".[16]

The only existing complete set of Washington's dentures is owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, who own and operate George Washington's estate in Fairfax County, Virginia. There is another complete, original, lower jaw denture dated 1795 at the National Museum of Dentistry in Baltimore, Maryland.[17]

Dentists

[edit]

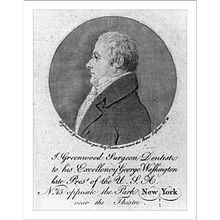

At least three of Washington's dentists are identified. His diary mentions "Doctor Watson", the dentist who pulled his first tooth. His personal dentist and friend was Jean-Pierre Le Mayeur.[7] John Greenwood of New York City made and maintained his dentures.[7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Smithsonian Institution states in "The Portrait—George Washington: A National Treasure":

Stuart admired the sculpture of Washington by French artist Jean-Antoine Houdon, probably because it was based on a life mask and therefore extremely accurate. Stuart explained, "When I painted him, he had just had a set of false teeth inserted, which accounts for the constrained expression so noticeable about the mouth and lower part of the face. Houdon's bust does not suffer from this defect. I wanted him as he looked at that time."

Stuart preferred The Athenaeum pose and, except for the gaze, used the same pose for the Lansdowne painting.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Wills, Matthew (2020-02-25). "Were George Washington's Teeth Taken from Enslaved People?". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ a b Kirschbaum, Jed (January 27, 2005). "George Washington's false teeth not wooden". msnbc.com. The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ "George Washington's Teeth". George Washington's Mount Vernon.

- ^ "George Washington's Troublesome Teeth". Lives & Legacies. The George Washington Foundation. 2017-05-18. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Schultz, Colin. "George Washington Didn't Have Wooden Teeth—They Were Ivory". Smithsonian.

- ^ a b Pappas, Stephanie (3 March 2018). "What Were George Washington's Teeth Made Of? (It's Not Wood)". Live Science.

- ^ a b c d e Andrews, Evan (18 February 2020). "Did George Washington have wooden teeth?". HISTORY.

- ^ "Did George Washington's false teeth come from his slaves?: A look at the evidence, the responses to that evidence, and the limitations of history". washingtonpapers.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "George Washington's Teeth". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ "George Washington and Slave Teeth". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Mary V. Thompson, "The Private Life of George Washington's Slaves", Frontline, PBS

- ^ "Teeth". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ^ a b c "The Portrait—George Washington:A National Treasure". Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "FACT CHECK: Did George Washington Have Wooden Teeth?". Snopes.com. 21 December 2016.

- ^ Stuart, Gilbert. "George Washington (the Athenaeum portrait)". National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Etter, William M. "George Washington's Teeth Myth". www.mountvernon.org. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ ""De-aging" George Washington". Smithsonian Affiliations. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019.